- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

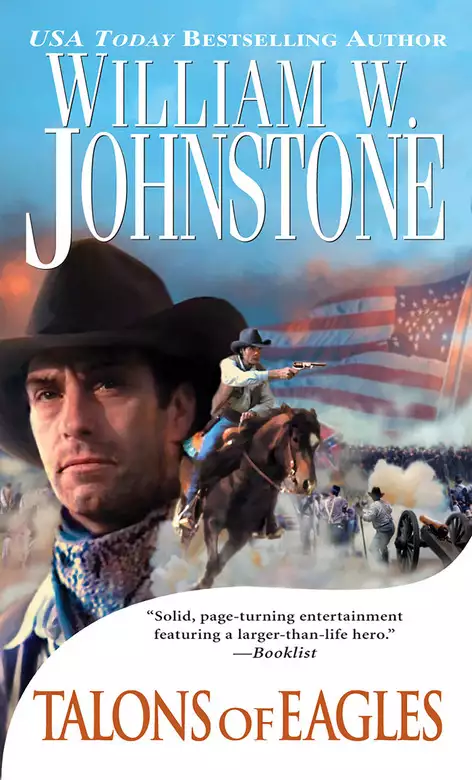

"Solid, page-turning entertainment featuring a larger-than-life hero in MacCallister" from the greatest Western writer of the twenty-first century (Booklist).

Divided they fall . . .

Raised by the Shawnee, Jamie Ian MacCallister fought his way to manhood on an odyssey that took him from the Alamo to Colorado to the goldfields of California. Now, the United States is divided against itself—North against South, brother against brother, father against son. With his own sons fighting on opposing sides, MacCallister leads his Confederate Marauders into battle from Georgia to Tennessee, from Bull Run to Shiloh.

When the guns of war finally fall silent, a vengeful enemy vows to add another chapter to the bloodstained pages of history . . . by hunting down the soldier named Jamie Ian MacCallister.

"[A] rousing, two-fisted saga of the growing American frontier." —Publishers Weekly

Release date: July 26, 2016

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 350

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Talons Of Eagles

William W. Johnstone

But civilization did not take well to Jamie. He was wise far beyond his years, tall and strong for his age, and could hold his own in any fight, fists or blade, with boy or man. There was no back-down in Jamie MacCallister.

Then he met Kate Olmstead, the most beautiful girl Jamie had ever seen, and he fell head over moccasins in love. Kate had hair the color of wheat and eyes of blue. She wasn’t very big, but with a smile and a wink she could twist Jamie right around her pretty little finger. Jamie became so smitten the first time he saw Kate, he walked right into a tree and almost knocked himself goofy.

If there ever was a love made in heaven, it was Jamie Ian MacCallister and Kate Olmstead. There was only one hitch: Kate’s father and her brother hated Jamie.

But that didn’t stop the two from seeing each other and holding hands whenever they could.

When Jamie was fourteen years old, he looked twenty, was well over six feet tall, and literally did not know his own strength. He wore his thick blond hair shoulder length and shunned store-bought clothes and homespuns in favor of buckskins.

Then he had to kill a man.1

It was self-defense, but suddenly Jamie found himself a wanted man with a price on his head. He took to the deep woods of Western Kentucky, but would not go far because of his love for Kate. After only a few months, Jamie returned and the two of them eloped. They were married in the river town of New Madrid, Missouri, and wandered westward, finally stopping in the Big Thicket country of East Texas. There, they settled in and began to raise a family. Jamie’s neighbors were a runaway slave, Moses Washington, and his wife, Liza, and their children. A few years later, several families from back in Kentucky showed up in the Thicket: Sam and Sarah Montgomery, and Hannah and her husband, Swede.

Jamie became involved with those seeking independence for Texas, and the night before the Alamo fell, he was sent out with a packet of letters from the defenders. Jamie was ambushed by one of Santa Anna’s patrols and left for dead. A poor Mexican family found him, more dead than alive, and took him into their home, helping to nurse him back to health until Kate could arrive and take him back to their cabin in the Big Thicket.

In the spring of 1837, Jamie and Kate, Moses and Liza, and the families from back east decided to move westward.

They settled in a long and lovely valley in Colorado; in the coming years it would be known as MacCallister’s Valley. It was there Kate and Jamie’s tenth and last child, Falcon, was born in 1839. All had survived except baby Karen, who had been born in the Big Thicket country and was killed by bounty hunters at five months of age in 1829.

Jamie made friends with those Indians who would accept his friendship, and fought with the others. The name of Jamie MacCallister became legend throughout the West, as scout and gunfighter, and a man who had damn well better be left alone, just as the MacCallister children were making names for themselves as they grew into adulthood. Their oldest boy, Jamie Ian, Jr., who was born in 1827, was a man feared and respected by both whites and Indians. Jamie Ian did not begin to settle down and hang up his guns until he married Caroline Hankins and built a home in the valley.2

The second set of twins, Andrew and Rosanna, showed an early interest in music and were sent back east to school. In the coming years both would become world-renowned musicians, composers, and actors.

Life was good for Jamie and Kate in the valley, and they were content to watch the town they founded grow and their kids mature and marry and have children of their own.

But Jamie MacCallister was too famous a man for the public to forget. When he was fifty years old, he received word that President Abe Lincoln wanted to see him.

“You can’t go meet the president of the United States looking like you just came off a buffalo hunt, Jamie,” Kate told him.

“Why not? ”

“Hold still!” Kate said, measuring him across the shoulders. “Your good black suit will fit you, but I’ve got to make you some shirts.”

“What’s wrong with buckskins?”

“Hush up and hold still.”

Time had touched the couple with a very light hand. Their hair was still the color of wheat, with only a very gentle dusting of gray. Kate was still petite and beautiful, and Jamie was massive. The few suits he owned had to be tailor-made because of the size of his shoulders, chest, and arms. His hands were huge and his wrists thicker than the forearms of most men. Even at middle age, Jamie still truly did not know his own strength. He had killed more than one man with just a blow from his fist. But with Kate, the kids, and those he loved, Jamie was gentle.

“What did the letter from Falcon say?” Megan, one of the triplets, asked.

Kate stepped around Jamie and looked up at him, questions in her eyes.

Falcon, the youngest of the MacCallister children, had left home when scarcely in his teens and quickly made a reputation as a gambler and gunfighter. He did not cheat at cards, although he could; he just knew the odds and played expertly. He had his father’s size but not his father’s easy temperament. Falcon’s temper was explosive, and he was almighty quick with a pistol.

Jamie said, “He joined up with some outfit in Texas. He was scout for that bunch who attacked Fort Bliss.”

“Then the war is really happening, Pa?” Megan asked.

“Yes.”

“I just can’t believe that Falcon would fight for any side that believed in slavery,” Ellen Kathleen said.

Kate looked at her oldest daughter. Like all MacCallister children and grandchildren, Kathleen’s eyes were blue and her hair golden. It was difficult for Kate to believe that Kathleen was in her mid-thirties and had children of her own that were very nearly old enough to marry. “Falcon does not hold with slavery, Ellen Kathleen,” the mother said. “I’m told the war is not really about slavery. It’s about something called states’ rights. Isn’t that so, Jamie?”

“Damn foolishness is what it is,” Jamie said. “And if Honest Abe thinks I’m going to get mixed up in it, he has another think coming.”

“Don’t speak of your president like that!” Kate said sharply. “You be respectful, now, you hear? Abe Lincoln is a fine man with a dreadful burden on his shoulders. If he needs your help, you’re bound and obliged to help out—and you know it.”

“I thought you said I was too old to be traipsin’ about the country, Kate?” Jamie said, with a twinkle in his eyes. He let one big hand slip down from Kate’s waist to her hip.

She slapped his hand away as those kids present howled with laughter.

“You mind your hands, Jamie MacCallister!” Kate snapped playfully at him. “Time and place for everything.”

“I’ve got the time,” Jamie said. “If you’ve got the place, old woman.”

“Old woman! ” Kate yelled. “Get on with you!” she said, amid the laughter of kids and grandkids. She shoved at him, and her shoes started slipping on the smooth board floor. It was like trying to move a boulder. “Get outside, Jamie! I’ve got to finish these shirts. Megan, you and Ellen Kathleen get your sewing kits and help me. We can’t have your father going to Washington looking like something out of the rag barrel.”

Joleen MacCallister MacKensie, who had married Pat MacKensie in 1851, came busting up onto the porch. “Pa! Will you come talk to your grandson Philip and tell him to stop bringin’ home wolves. He’s done it again! Now, damnit, Pa . . .”

Kate pointed a finger at the young woman. “I’ll set you down and wash your mouth out with soap, young lady. You mind that vulgar tongue, you hear me?”

Joleen settled down promptly. She knew her mother would do exactly what she threatened. “Yes, Ma. But somebody’s got to talk to Philip. Last year he brought home a puma cub and like to have scared us all to death when the mother showed up!”

Jamie rattled the windows with laughter at the recalling of that incident. He clapped his big hands together and said, “I recollect that morning. Pat was on his way to the outhouse with his galluses hangin’ down and come nose to snout with that angry cat. I never knew the boy could move that fast.” Jamie wiped his eyes and chuckled. “He came out of his britches faster than eggs through a hen. If that puma hadn’t a got all tangled up in Pat’s britches and galluses, that would have been a tussle for sure. Pat never did find his pants, did he?”

It would be many a year before Pat MacKensie would live that down.

“Pa!” Joleen yelled, red in the face.

“All right, all right. I’ll go talk to Philip. Calm down.”

“Get your sewing kit, Joleen,” Kate said. “We’ve got work to do. And bring what’s left of those buttons I lent you.”

“Yes, Ma.”

Jamie stepped outside and looked up and down the street of the town. Two nearby towns, separated by only a low ridge of hills, were called Valley. Several hundred people now lived in the twin towns. They had a doctor, several churches, a block each of stores, and a large school house that served both towns.

Jamie thought about his upcoming trip east. He was to ride out in three days, crossing the prairies, then into Missouri, and then catch the train east to Washington. Jamie smiled. Tell the truth, he was sort of looking forward to it.

Jamie stayed to himself as much as possible during the train ride eastward, which was not easy since the coaches were filled with blue-uniformed soldiers of the Union army, all excited about the war. To a person, they were convinced the war would not last very long, and all were anxious to get in it before it was over—promotions came fast in a war.

Jamie was not so sure the war would be a short one. And he was even more baffled as to why the president of the United States wanted him to scout for the Union army. Jamie knew almost nothing about the country east of the Mississippi; everything had changed since he’d left that part of the country, more than thirty years ago.

Jamie looked at the fresh-faced young officers on his coach, and listened to them talk of the war, as the train whistled and clattered and rattled through the afternoon.

“Those damn ignorant hillbillies,” one young second lieutenant said. “They really must be stupid if they think they can whip the Union army.”

Those damn hillbillies, Jamie thought, can take their rifles and knock the eye out of a squirrel at three hundred yards, sonny-boy.

“The Army of Virginia is a joke,” another lieutenant said. “And Lee is nothing more than a damn traitor.”

Lee is no traitor, Jamie thought. He is a Virginian and a damn fine soldier. How could he turn his saber against the state that he loves?

“We’ll whip those mush-mouthed Southerners in jig-time,” another young officer boasted.

Don’t be too sure of that, Jamie thought. He stood up and walked to the rear of the car, stepping out to breathe deeply of the late spring air. The conductor had said several hours before that they would be in Washington sometime during the night.

Jamie felt strangely torn, as a myriad of emotions cut through him. His family, like so many others, had roots in both the North and the South, although his mother’s side of the family had settled in South Carolina many years before the MacCallister clan came to America. Jamie had been so young when his parents and baby sister were killed and the cabin burned, he did not know his mother’s maiden name.

He sensed more than heard the door open behind him and cut his eyes. The man who was stepping out smiled at him. “Mind if I join you for a smoke?”

“Not at all,” Jamie replied.

“Boastful young soldier boys in there,” the man said.

“They’ll soon learn about war.”

“That they will, friend. That they will. Traveling far?”

Jamie smiled. “Not too far.” Jamie’s smile had been forced, for the man had a sneaky look about him that Jamie did not care for; he took almost an instant dislike for the fellow. Jamie had learned while only a boy to trust his finely honed instincts. They had saved his life many times during the long and sometimes violent years that lay behind him.

“A sorry thing this war,” the man said, after lighting a cigar. “After the Union is successful in bringing those damned Southerners to their knees, we should put them all on reservations like we’re doing with the Injuns and let the damned worthless trash die out.”

“There is right and wrong on both sides in any war, friend,” Jamie said.

A dangerous glint leaped into the man’s eyes, and he moved his hand, hooking his right thumb inside his wide belt. “Not in this war, friend. No man has the right to hold another as slave.”

“You’re right,” Jamie agreed, and the man seemed to relax somewhat. But his right hand stayed where it was. Hide-out gun or knife, Jamie thought. Or both. Jamie was carrying a gun and knife of his own. He carried a .36 caliber Colt Baby Dragoon in a shoulder holster, and a knife sheathed on his belt. “Slavery is wrong.”

“Southerners are filthy trash,” the man said. “You agree with that?”

The man is determined to force an argument, Jamie silently concluded. But why? And why with me? Jamie placed both hands on the iron railing and stared at the countryside as the train rolled on. Only a few minutes until dusk, Jamie noted, and the stranger’s stance was aggressive. He’s going to jump me! Jamie thought suddenly. But why? “No, mister. I don’t agree with that.”

“Can’t straddle the fence in this conflict,” the man said, a wild look in his eyes. “And now I know who you are.”

“Oh?”

“You’re a damned filthy secessionist! Our intelligence was right.”

“What the hell are you talking about?” Jamie asked, irritation plain in his words.

The man’s eyes were burning with a fanatical light. He moved his hand under his coat. “Long live the memory of John Brown!” he said, just as the train began moving through a shady glen. That, coupled with the fast-approaching dusk of evening, plunged the train into near darkness. The man whipped out a knife and lunged at Jamie.

But Jamie had anticipated trouble. He clamped one huge hand on the man’s wrist and stopped the knife thrust. He hit the man a vicious blow to the jaw with his left fist, and the man’s eyes glazed over. Jamie twisted the man’s knife arm, and the pop of the bone breaking was loud even over the rumblings of the train. The assassin opened his mouth to scream in pain just as Jamie took a step backward for leverage and hurled the man from the platform of the coach. The man bounced and rolled beside the tracks and then lay still. Whether he was alive or dead, Jamie did not know, and did not care.

“Idiot,” Jamie said. The train rolled on, and he quickly lost sight of the fanatical abolitionist.

Jamie, of course, had read of the exploits of John Brown, and considered the man to be a fool.

The car in which Jamie had been riding was the last one of the hookup, so it was doubtful that anyone else had seen the brief confrontation and the man being thrown from the platform—but there was always that chance. Jamie waited for some sort of outcry, but none came.

Jamie stood for several minutes on the platform, wary now of his surroundings, but still deep in thought.

Somebody has learned of my invitation to meet with the president and doesn’t want me to attend. But why? I have not committed to either side in this war, and as it stands now, I probably won’t. I have no interest in this war.

But if there are any more attempts on my life, I will develop a very personal interest in the conflict.

“And take appropriate action,” he concluded aloud, just as the sun sank over the horizon and night covered the land.

“I am E.J. Allen,” the short, stocky man said, with a definite Scottish burr to his words. “Welcome to Washington, D.C., Mister MacCallister.”

The man’s real name was Allan Pinkerton, owner and founder of the soon-to-be-famous Pinkerton Detective Agency. And a man who many say founded the United States Secret Service. During the early days of the Civil War, or the War Between the States, as many called it, Pinkerton often worked under the name of Major E.J. Allen.

“The carriage is this way, sir,” Allen said.

Jamie picked up his bag and followed the man through the busy train station. Seated in the closed carriage, Allen asked, “Did you have a pleasant trip, sir?”

“Very pleasant,” Jamie replied. He had made up his mind to say nothing about the attempt on his life. There were some things he wanted to sort out in his head.

E.J. Allen said not another word from the train station to the White House. Jamie could sense that the man either did not like him, or did not trust him, or a combination of the two. He also, for some reason, did not believe E.J. Allen was the man’s real name.

At the rear entrance, Allen finally spoke. “I’ll take your pistol and your knife, Mister MacCallister.”

“If you get them, you’ll take them,” Jamie told him, then stepped from the carriage and walked up the steps.

“Sir!” Allen called.

A tall, almost emaciated appearing man stepped into the lamp-lit doorway. “Let him be,” the man said in a deep, resonant voice. “And leave us alone, please.”

Inside, Jamie was shown to a private room on the ground floor of the huge, three-story mansion and was served a hot meal by a Negro servant. As he was eating, Lincoln appeared and sat down across the table from him. A cup of coffee was placed in front of the president, and the servant left without saying a word, closing the door behind him.

Lincoln took a sip of coffee and smiled. “Your admirers said you were a large man, Mister MacCallister. But they did not do you justice. And you do not look your age, sir.”

“Thank you, Mister President.” Jamie laid down his knife and fork.

Lincoln waved a hand. “Eat, sir, eat. I know you must be ravenous after such a long and tiresome journey. You eat, I’ll talk. Is the meal to your liking?”

“Yes, sir. It’s very good.”

“You’re a very famous man, Mister MacCallister—”

“Jamie, sir. Please.”

“Very well. Jamie, it is. Hero of the Alamo. Pioneer. Trailblazer and scout. Indian fighter. I’ve heard the songs about you, read the books and articles, and I saw the play about your life when it played in Springfield. How do you feel about this war that has started?”

“I don’t hold with slavery, sir.”

“It isn’t about slavery . . . although that does play a very minor part in the conflict. I have friends in Alabama and Georgia, and several other Southern states, who were talking about freeing their slaves long before the war talk started. It’s about . . . well, whether this nation survives whole, or tears itself apart and crumbles.”

“Looks like to me the tear has already started, sir.”

Lincoln shook his head. “The South can’t win, Jamie. It is going to be a very long war, and a costly one in terms of human life, but the South cannot win. We have the factories, the man power, and the wherewithal to sustain for years. The South simply does not.”

Jamie said nothing. He ate his beef and potatoes and green beans in silence.

“You could help bring this terrible tragedy to a sooner end, Jamie,” the president spoke the words softly.

Jamie met the man’s eyes, and in those eyes he could see what a burden the man carried. “You’re asking me to fight against my own son, Mister President?”

Lincoln stood up, almost painfully, Jamie noted. Bad knees, probably. The president walked around the small meeting room. He sighed and faced Jamie. “I did not know you had a son fighting for the Confederacy.”

“Falcon. My youngest. He’s twenty-one. And my oldest boy, Jamie Ian, is talking about taking up arms for the Blue. Matt might go with the Blue, too. I don’t know. But he’s leaning that way. I hope they both stay in Colorado. But all you can give a child is roots and wings. They got to make up their own minds. Andrew is in Europe, and his ma and I wrote him and told him to stay there; stay out of it. My grandfather came from Scotland; my mother’s people came from South Carolina, I think. Somewhere in the South. I’m just not sure. I know I feel a great pull toward the Confederacy.”

Lincoln smiled very sadly and drained his coffee cup. He said, “Then you must go where your heart dictates, Jamie. I personally despise slavery. But if I could save the Union without freeing a single slave, I would do so.”

On August 22, 1862, in a reply to Horace Greeley, Lincoln wrote: “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”

“I want you to think about becoming my chief of scouts, Jamie MacCallister,” Lincoln said. “It would be a great boon to the Union if you would accept the position. If you do not, I will understand.”

“Yes, sir. I promise you I will think about it.”

Lincoln extended a hand, and Jamie took it. “I have made arrangements for you to stay at a nearby hotel. My carriage driver will take you there. Good luck and God bless you, Jamie MacCallister.”

“And good luck and God bless you, sir.”

Lincoln left the room, and Jamie pushed the plate from him and refused the offer of more coffee from the servant. He walked outside to stand for a moment in the night air. Warm for this time of year, Jamie noted. He felt eyes on him and turned around, glancing up at the second floor. Lincoln was standing, looking out a window at him. Jamie lifted a hand in farewell and Lincoln did the same.

“A great man, there,” E.J. Allen spoke from his position beside the carriage. “With a terrible burden on his shoulders.”

“Yes,” was Jamie’s reply. “And it’s not going to get any lighter.” He stepped into the carriage without another word.

A full decade before the Southern states elected to secede from the Union, another revolution was taking place—in the North. By 1860, the Northern states held four-fifths of the nation’s factories, more than two-thirds of the railroads, and nearly all of the shipyards. The term “Yankee ingenuity” had become a commonplace word in all the civilized countries of the world.

The South had slaves and pride and something else: the South knew that should the Federal government win the war and states’ rights become a thing of the past, in the years to come, the Federal government would have too much control over the lives of American citizens.

Lincoln was right in maintaining that the South could not win this war. But everybody, the president included, was wrong about the duration. The war would last for four long, bloody years, and during that time, just under three-quarters of a million Americans would die. The war would cut deeply across the fabric of America, leaving wounds that would never heal, and would divide families forever.

Washington was an armed camp, filled to overflowing with soldiers ready to defend the nation’s capital. But it was an unnecessary move. At the time, Washington was in no danger from armed invaders.

The morning after meeting with the president, Jamie carefully packed his suit and changed into buckskins. He roamed the city, inspecting several dozen horses before he finally chose one to buy. He bought supplies, a brace of pistols, and a rifle. Then he crossed the Potomac and headed south into Virginia.

Just across the river, he stopped and sat for a time under the shade of a huge old tree and read the newspapers he’d bought in Washington.

About a third of the experienced army officers had resigned to take up arms against the Union; among them were Johnston, Beauregard, and Lee. One-fourth of the experienced naval officers had joined the Confederacy.

Baltimore was about to come under attack, the newspapers stated.

It never happened. General Butler quickly moved troops into place and put down any still-vocal secessionists. Butler further added insult to injury by stating that he had “... never seen any Maryland secessionist force that could not be put down by a large yellow dog.”

Lincoln had put out the call for volunteers on April 15, 1861. They poured in to join up, hundreds of thousands of them. In contrast, the Confederacy had just less than sixty thousand troops, active and in training. In 1861, the population of America was just over thirty-two million, with more than two-thirds of that number living in the North. The South had barely nine million citizens, with more than a third of them slaves, barred from serving in the Confederate army because of white fear of an armed insurrection.

But it was the North’s industrial might that made the South’s pale in comparison. New York State had more factories than all of the South.

The South, however, had one crystal clear advantage: they would be defending their homeland. And they were ready and very willing to defend it to the last drop of Southern blood.

Jamie looked up from his reading at the pounding of hooves. A troop of cavalrymen, dashing in appearance in their gray and gold uniforms, with the officers wearing plumed hats, came galloping up and reined in on the road beside which Jamie was sitting.

“You there, woodsman!” the commanding officer said, his eyes taking in Jamie’s buckskins. “You’ve picked a peculiar place to rest.”

Jamie smiled at the man. “Oh? Why is that?”

“Well . . . there is a war on, my good fellow! This area could come under attack at any moment.”

“Not by me,” Jamie said. “I’m a Western man just passing through.” He held up the newspapers. “The only thing I know about the war is what I read.”

“Rest the men,” the captain said, dismounting and handing the reins to a sergeant. He walked over to Jamie and knelt down. “My friend, you are probably what you say you are, but these are tense times. You run the risk of being arrested as a spy.”

Jamie laughed. “I’m no spy, Captain. Although President Lincoln would probably settle for that.”

“Lincoln?”

“Yes. I met with him last evening.”

“I beg your pardon, sir?” the captain was quite taken aback by Jamie’s words.

Jamie rose to his full height, and the captain quickly stood up. Jamie towered over him. “I was offered a position in the Union army. I refused . . . in a manner of speaking. I have a son who is fighting with a Texas cavalry unit.”

“Good lad!” the captain said. “And your name, sir?”

“Jamie MacCallister.”

The entire troop of confederate cavalry fell silent. Everybody had heard of Jamie MacCallister. “The Jamie MacCallister?” the captain asked.

“I guess. Far as I know, there’s only one of me. I do have a son named Jamie Ian, but he’s back in Colorado.”

“Good God!” a young lieutenant breathed. “The man’s a living legend.”

One quick look from the captain silenced the ranks. He swung his gaze back to Jamie.

“And how was Mister Lincoln, sir?” the captain asked.

“Saddened by the war.”

“He has no need to be. He has only to give us independence and there will be no war.”

“He won’t do that, sir.”

“No. No, I’m sure he won’t. You have heard the Yankee side, sir. Would you be interested in hearing our side of the issue?”

“I would.”

“Excuse me for a moment.” The captain walked to the ranks, and a moment later, a rider galloped away, heading south. The captain returned to Jamie’s side and extended a hand. “I am Captain Cort Woodville, sir—of the Virginia Scouts. There is someone I would very much like for you to meet.”

Kate was sitting on the front porch with Ellen Kathleen, Megan, Joleen, and Jamie Ian’s wife, Caroline. The ladies were rocking and talking and sewing.

“Jamie Ian is going off to war, Ma,” Caroline said.

Kate did not pause in her rocking or her sewing. “Oh? He tell you that?”

“No, Ma. But I can see it in him.”

“Matthew is going to resign his commission as sheriff and join up with the Blue,” Ellen Kathleen said. “And yes, he told me. He was scared to confront you himself, Ma.”

Kate still did not cease her rocking. But she did lay her sewing in the basket beside the chair. “Then so far we’ll have two for the Blue, and two for the Gray.”

“Who besides Falcon, Ma?” Joleen asked.

“Your father, dear.”

“Pa don’t hold with slavery, Ma!”

“No. But he’ll almost always take up for the underdog. Did any of you know that Wells and Robert rode out yesterday? We’re going to be short on men-folks for a time.”

“Wells and Rober. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...