- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

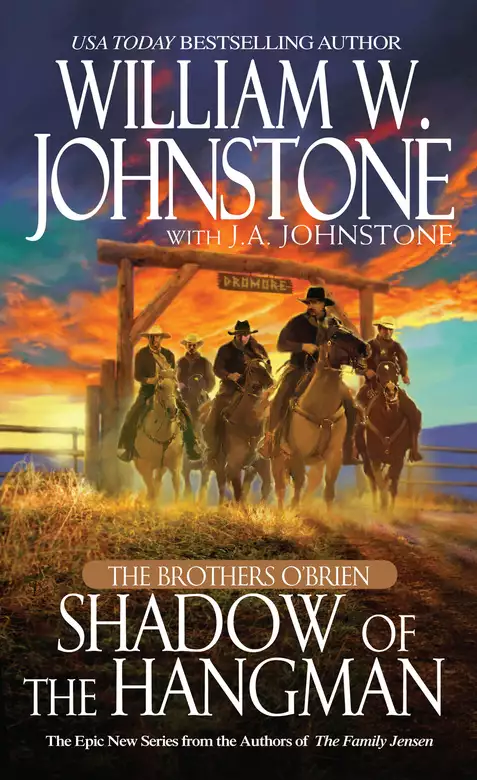

The Greatest Western Writer Of The 21st Century William W. Johnstone, the USA Today bestselling master of the epic Western, continues the saga of the four O'Brien brothers--bravehearted men working and fighting the untamed lands of New Mexico Territory to build a dream of America. The Hangman Cometh. . . When a farmer's wife is murdered, an innocent man is accused: Patrick O'Brien. The book-loving brother had shared his love of literature with the woman, but her husband claims she spurned Pat's advances and that's why he killed her. Now it looks like Patrick will swing from the gallows--especially after his lawyer is targeted, too. Pat's brothers try to track down the real killer, but time is running out. A team of hired guns has come to town, and they're choking the family ranch like a noose. For the brothers O'Brien, it's judgment day. And justice will be served--in a hellstorm of blood and bullets. . .

Release date: November 14, 2013

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 401

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Shadow of the Hangman

William W. Johnstone

“I didn’t kill her, John,” Patrick O’Brien said. “Molly Holmes and I were good friends.”

“I know you didn’t kill her,” Moore said. “But three people saw you leaving the barn, and they say otherwise.” The sheriff, a middle-aged man with tired eyes, moved his checkers piece. “Crown that.”

Patrick sat back in his chair and smiled. “I give up, John. I can’t beat you at this game.”

“How many is that? Eighteen in a row?” Moore asked.

“Twenty-three to be exact,” Patrick said.

“Maybe you’ll win next time.”

“I doubt it. You know what move I’m going to make before I make it.”

“That’s the secret to being a good checkers player, Pat.”

The office door opened and Moore rose to his feet. His hand dropped to his holstered Colt, the ingrained habit of twenty-five years of law enforcement. But when he saw who stepped inside, he smiled and stuck out his hand. “Sam, good to see you again.”

Samuel O’Brien took the proffered hand and said, “Howdy, John. I brought Patrick some books.” He laid a stack of volumes on the sheriff’s desk. Then to his brother he said, “How are you holding up?”

“All right, I guess,” Patrick said, examining the book spines. “Except that John keeps beating me at checkers.”

“John beats everybody at checkers,” Samuel said.

“Ah,” Patrick said, his face brightening, “a brand-new volume of Keats.”

“Lorena’s idea. She said he’s your favorite poet.”

“Poetry should be great and unobtrusive,” Patrick said, “a thing which enters one’s soul, and does not startle it or amaze it with itself, but with its subject.”

“Hell, Pat,” Moore said, “did you just set there and make up them highfalutin words?”

“No, the poet John Keats made them up sixty years ago.”

“Oh,” Moore said. “It would take me a spell to work all that out in my mind.” He looked thoughtful. “I wonder if that Keats feller played checkers.” He got no answer to his question and put his hand on Patrick’s shoulder. “Sorry, Pat, but I’ve got to lock you up again.” The sheriff’s face was apologetic. “It’s for appearances’ sake, like.”

Patrick rose to his feet, his leg shackles clanking. “I understand, John. You’ve got a job to do.”

“Do you really need to keep my brother chained up like an animal?” Samuel said, his anger flaring.

“Sorry, Sam, but it’s the law.”

“Whose law?”

“The Vigilance Committee of Georgetown, fairest city in the New Mexico Territory.”

“Who says it’s the fairest?” Samuel said.

“The Vigilance—”

“I get it, John,” Samuel said.

Patrick shuffled toward his cell, partitioned from the rest of the office by a limestone wall and steel-reinforced door. Before the door slammed shut behind him, Patrick turned and said, “How’s the colonel taking this, Sam?”

“As you might expect,” Samuel said. “He says if there’s any move to hang you, he’ll burn down this town and shoot every man who had a hand in declaring you guilty.”

Suddenly John Moore was worried. “Samuel, any more talk like that from your pa and I’ll bring in the army to keep order. Patrick was tried and convicted of rape and murder by a jury of his peers, sentenced by a judge, and there’s an end to it.”

“Do you think my brother is guilty, John?” Samuel said.

“No, I don’t.”

“Then who is?”

“I don’t know that, either.”

“John, Dromore won’t stand aside and see one of its own hang for a crime he didn’t commit.”

“Pat was found guilty in a court of law, not a court of justice,” Moore said. His eyes hardened, became dangerous, and the warning signs of the former gunfighter glowed in their blue depths. “I’ll enforce the law, Sam, anyway I have to.”

Samuel nodded. “Our quarrel is not with you. Somebody raped and murdered Molly Holmes and pinned the blame on Patrick. Whoever and wherever he is, I’ll find him.”

Moore turned his head and looked at Patrick. “Remember to turn the key in the lock when you get inside, huh?”

After the iron-bound door closed behind Patrick, Moore said, “Sam, I’ll help you any way I can, but you’ve only got seven more days and your brother hangs. I don’t know if it was a poet who said it, but time flies.”

Samuel stepped to the window and stared outside. The hard work of running a cattle ranch in an unforgiving land had drawn him fine. He was tall, slim, dressed in a worn blue shirt crossed by wide canvas suspenders. Shotgun chaps, boots, and a brown, wide-brimmed hat completed his attire, but for the Colt he wore, horseman-style, high on his right hip. His dragoon mustache and hair were both neatly trimmed, a little dictate of his wife.

Samuel’s eyes roamed over the single dusty street that made up the fair city of Georgetown. Clapboard, false-fronted buildings elbowed each other for room, and two saloons, both of adobe, stood near the railroad spur and cattle pens.

Only the town’s more respectable element braved the midday heat, businessmen sweating in broadcloth, women in cotton dresses, carrying parasols, and a few booted and bearded miners just in from the hills. The rough crowd, a few of them leftovers from the recent Estancia Valley range war, would not show up until lamps were lit in the saloons and the girls from the line shacks came out to play.

Georgetown was a mean, miserable burg, held together with baling wire and spit, and Samuel O’Brien figured it had not earned the right to hang a man.

He turned away from the window and said, “John, I’ve got to be going. If Patrick—”

“Needs anything, I’ll see he gets it,” the sheriff said.

Samuel smiled. “You read minds, John.”

“Yeah, I do, and that’s why I keep beating your brother at checkers.”

The office door burst open with a bang, the calling card of a man determined to make a grandstand entrance.

Elijah Holmes strode into the room, his boots thudding on the rough pine floor. He held a Bible in one hand, a coiled bullwhip in the other.

“I want to see him, Sheriff,” he said. “I will read to that papist son of iniquity from the book, then whip the fear of the one true God into him.”

Moore blocked Holmes’s path. “I told you already, Elijah, you can’t see the prisoner.”

The farmer was a tall skinny man wearing stained overalls. He had a shock of gray hair, and a beard of the same color spread over his narrow chest. His eyes blazed the wild look of a mentally unbalanced fanatic.

Samuel thought Molly Holmes’s husband looked like a deranged Old Testament prophet, and he placed himself between the farmer and the door to the cells.

“Sheriff, he raped my wife, then crushed her skull with a blacksmith’s hammer,” Holmes said. “It is my right.”

“You’ll attend Patrick O’Brien’s hanging,” Moore said. “That’s the only right you have.”

“Damn him to everlasting fire,” Holmes screamed. “Did you see my wife’s body?”

Moore nodded, remembering. “I saw it.”

“Naked, bitten, torn, ravaged, a red-hot poker thrust into her sinful womanhood.” He shoved his face into Moore’s, saliva dripping from his lips. “Did you see it?”

The sheriff nodded, but said nothing.

“She was a whore!” Holmes shrieked. “Patrick O’Brien seduced her with his books and his smooth ways, reading poetry to her and filthy novels. There is only one book that should be read.” He raised the Bible high. “The one I hold in my hand.”

Suddenly Holmes looked crafty. “Do you see this?” He shook the bullwhip. “How many times did I use this on her, trying to make her change her ways and return to the sweet bosom of the Lord?”

“I don’t know,” Moore said, his face stiff.

“A score! Two score! Yet she continued with her vile fornications under my very roof.” Holmes stopped for breath, then said in a quieter tone, “Then, ’twas the last time I whipped her, she vowed to change her shameful ways. But what happened? Along came Patrick O’Brien with his books and silken tongue, and she refused to give him what he wanted.” Holmes let his thin shoulders sag. “Enraged, he forcibly satisfied his wicked lusts, then killed her, finally despoiling that which she had refused to uncover to him willingly.”

His gorge rising, Samuel said, “Mister, your wife had a name.”

“I know she did, O’Brien, and be damned to ye for being kin to evil’s spawn.”

“What was it? What was her name?”

“I won’t sully my tongue with the name of a whore,” Holmes said. He glared at Moore. “Let me pass, Sheriff.”

“You’re not going in there,” Moore said. “This is a jail, not a carnival sideshow.”

“I won’t give him the whip, since it troubles you so much, Sheriff. But I’ll read to him from Scripture and reveal to him the error of his ways.”

“Mister,” Samuel said, his hand close to his holstered Colt, “this is a friendly warning—one step toward the door to the cells and I’ll drop you right where you stand.”

Holmes’s eyes widened in shock. “Sheriff Moore, did you hear that?” he gasped. “This man threatened me.”

“I didn’t hear a thing,” the big lawman said. “Now get the hell out of here, Holmes, before I arrest you for disturbing the peace.”

“So that’s it,” Holmes said, “you’re in cahoots with the high-and-mighty O’Briens and their millionaire pa.”

“Holmes,” Moore said, his face tight with anger, “scat!”

The farmer nodded. “I’ll scat, all right, but I tell you one thing”—he directed his gaze at Samuel—“the day your brother hangs, O’Brien, I’ll dance on the gallows and piss on his grave.”

The farmer turned and flung through the door, but he stopped, turned, and stabbed a finger at Samuel. “O’Brien, from now on, your life ain’t worth spit.”

“Right nice feller, isn’t he?” Samuel said after Holmes was gone.

“He’s a mean one,” Moore said. “I think he gave Molly a miserable life.” He sat at his desk. “Then Patrick got her interested in books and she found a way to escape, at least for a while.” The sheriff opened a drawer and produced a bottle of Old Crow. “Too early?” he said.

“I could use a drink,” Samuel said. He took the glass from Moore’s hand, then said, “You think Holmes could have killed her?”

The sheriff took a sip of his bourbon before he spoke. “He could have,” he said. “That red-hot poker thing sounds like something he’d do.”

“Was Holmes ever a suspect?” Samuel said.

“No. He was seen as the grieving husband. If he murdered Molly, he sure acted the part of an innocent man.”

“Why didn’t you suggest that Holmes could be the killer, John?”

“Sam, I can’t accuse a man without proof,” Moore said. “Holmes and two of his hired men saw Patrick leave the barn at a gallop. When they went to investigate, they found Molly’s naked and very dead body. The proof of Patrick’s guilt was hard to refute. Just ask lawyer Dunkley.”

“Lucas Dunkley did his best for Patrick,” Samuel said. “He was up against a stacked deck from the git-go.”

Moore held up the bottle. “Another splash?”

“No, I’m fine,” Samuel said.

Moore poured himself another drink, then said, “At the trial you said Patrick rode to Dromore and reported the murder. I never could understand why didn’t he come to me?”

“He was in shock, John. He’d just found a woman he liked raped and murdered, and he came to Dromore for help. About a dozen of us went to the Holmes farm, but we found nothing.”

“But you did, Sam. You found that the only tracks to and from the barn were made by Patrick’s horse.”

Samuel nodded. “Yeah. That was pretty damning, huh?”

“At least that’s how the jury figured it.”

Samuel laid his glass on the desk. “Thanks for the drink, John. I’ve got to get back to Dromore.” As though he’d just remembered, he added, “The colonel sent for my brother Jacob.”

At first Moore seemed to take that last in stride, but then he shook his head and made a small groaning sound. “That’s the worst news I’ll hear today,” he said. “Or any other damned day.”

Samuel O’Brien was about to swing into the saddle when a voice from the opposite boardwalk froze him in place, his left boot in the stirrup.

“Sam, a word with you, if you please.”

Lucas Dunkley stood outside his office, a rare smile on his face.

“Be right with you,” Samuel said. He led his horse across the street, looped it to a hitching rail, and stepped onto the walk. “What can I do for you, Lucas?”

“Let’s go inside,” the lawyer said. “The heat is intolerable.”

Samuel agreed with that observation.

The sun, burning like a white-hot coin, had climbed higher in the sky and mercilessly hammered the land. Only the El Barro Peaks to the north, purple in the distance, looked cool. Georgetown smelled of hot tarpaper, pine resin, horse dung, and the sharp odor of the cattle pens down by the railroad spur. A faint breeze lifted skeins of dust from the street and fanned the perspiring cheeks of the respectable matrons on the boardwalks.

Lucas Dunkley’s office was small, dark, and dingy. The ledgers and law books on the shelves were dusty, as was the black mahogany furniture and the lawyer himself. Despite the heat, Dunkley wore dusky broadcloth, much frayed at the sleeves, and a high, celluloid collar. A small pair of pince-nez spectacles perched on the tip of his pen-sharp nose, attached to his lapel by a black ribbon.

After bidding Samuel to take a seat, Dunkley said, “I’ll be brief.”

The little man seemed to expect an answer, and Samuel said, “Yes, of course.”

“And to the point, you understand?”

“Yes.”

“Very well then, we can proceed. Your brother, the condemned Patrick O’Brien, is not guilty of the rape and murder of the late Molly Holmes.”

“I know,” Samuel said. “I wish you could’ve convinced the jury of that.”

“I did not have all the facts then,” Dunkley said. “I do now.”

Samuel leaned forward in his chair. “What? I mean—”

The lawyer held up a white, blue-veined hand. “Be circumspect, Mr. O’Brien. Be judicious. Be wary. Facts are indeed facts, but in a court of law they must be proved to be facts and not fancies. Do you understand?”

Samuel said he did, but in truth, he didn’t.

“Your brother is a pawn, Mr. O’Brien. He will be sacrificed so that a most singular evil may prosper and fulfill its ends.” Dunkley looked over his steepled fingers. “The evil was spawned here, in this territory, and it’s a cancer I intend to root out and expose to the world.”

“What sort of evil?” Samuel said. “Damn it, Lucas, give me something.”

“I can’t, not yet. Allow me a couple of days and I’ll reveal all.”

“We don’t have much time,” Samuel said. “Patrick hangs in seven days.”

“I am aware of that,” Dunkley said. “And I know that my own life is in terrible danger.” The lawyer smiled his wintry smile. “Yet I will proceed, perhaps more carefully. I must be cautious, prudent, circumspect, as you must be, Mr. O’Brien. This town has eyes and ears. You will be suspect because there are those who will think that you now know what I know. Do you understand?”

Samuel nodded. “Suppose I send a couple of my vaqueros as bodyguards, men good with the iron? You’d be safe then.”

The lawyer shook his head. “No, that would hamper my freedom of movement and hinder my investigation. I will carry a small revolver on my travels, and that will be sufficient.”

“Travels? Where?”

Dunkley smiled. “Not far, just out of town a ways.”

He rose to his feet. “Mr. O’Brien, at the moment I am all that stands between your brother and the gallows. I will not fail him.” He picked up a pile of papers from his desk and riffled through them. “Now, business matters press, so if I could beg your indulgence?”

Samuel rose to his feet. “Yes, of course.”

“Come back and see me two days hence at this same time,” the lawyer said. “I believe I shall have news of the greatest import then.”

“Take care of yourself, Lucas,” Samuel said.

As he left, the office wall clock chimed noon, as solemn and foreboding as a tolling church bell.

Samuel O’Brien rode west toward Dromore, the great plantation house his father had built at the base of Glorieta Mesa. He wanted to be there when Jacob showed up, if only to head off the usual friction between his brother and the colonel.

Pa insisted that Jacob’s place was at Dromore, running the ranch with his brothers, not forever roaming restlessly from place to place, earning a living by the speed of his gun.

It was a case of an irresistible force meeting an immovable object, and both parties were too hardheaded to realize there could be no compromise and no winner.

Samuel smiled and shook his head, remembering past clashes between the colonel and Jacob. He’d no confidence that this time would be different, though the fact that Patrick’s life hung in the balance could change things.

Samuel crossed Apache Canyon and was a mile west of the Pecos when he spotted dust on his back trail. At first he thought it a trick of the shimmering heat, but when he looked again he saw a veil of yellow lift above a ridge just a couple of hundred yards behind him.

A man on a horse makes a fine rifle target, and Dunkley’s warning had made Samuel wary. He swung out of the saddle and led his buckskin to a stream that ran clear and cold off the mountains. He let his mount drink, his eyes on the ridge. The dust was gone.

Samuel got down on one knee and with his left hand cupped cold water into his mouth. His eyes moved constantly in the shadow of his hat brim. The hilly, treed land around him was still, silent, waiting . . . but for what?

The answer came when an exclamation point of water spurted from the stream, followed by the roar of a rifle. Samuel dived to his right, rolled, and fetched up against a barkless tree trunk, its white branches rising above his head like skeletal arms. He drew his Colt, wishful for the Winchester on his saddle, and raised his head above the trunk.

Samuel saw nothing, but a second bullet chipped splinters from the dead tree. Whoever the bushwhacker was, he had him pinned.

A drift of white gun smoke rose from a stand of juniper and piñon about fifty yards to Samuel’s right. He thumbed off a shot in that direction, a forlorn hope with a short-barreled Colt’s gun. He’d no idea where his bullet went.

A couple of minutes ticked past. Samuel had no shade, and the relentless sun hammered him, drawing sweat from his armpits and the middle of his back. The land undulated in the heat as though hiding behind a row of transparent snakes. Nearby, insects made their small sound in the grass, and a bashful breeze stirred the pines.

The crack of the rifle and the burn of the bullet came at the same time.

Samuel felt a sting on the outside of his right knee. He glanced down and saw that his pants were torn and already bloodstained.

He cussed a blue streak. The bushwhacker had moved, and the bullet had come from behind him to his right. He should be dead, but wasn’t. That could only mean the would-be killer was not a fair hand with a rifle, and Samuel wasn’t about to make it easy for him.

He rolled on his back and pinpointed the smoke drift, a gray smear forty yards away among a stand of juniper and scrubby wild oak.

They say that fortune favors the brave, and Samuel was about to try to prove it.

He swallowed hard and rubbed sweat from his gun hand. Then he fisted the Colt again, jumped to his feet—and charged.

His wounded knee felt a little gimpy as Samuel ran for the trees, but it was holding up well. A bullet kicked up dirt at his feet, and a second one split the air close to his head. He shot at the smoke, shot again—wild, inaccurate fire—hoping it might keep the gunman’s head down.

As it turned out, he’d played hob.

The rifleman stepped out of the trees, a Winchester to his shoulder. The man seemed unhurt, but Samuel figured his bullets must have come close enough because the bushwhacker was looking to end it.

The distance was twenty yards, and for a moment the eyes of the two men met and held, and Samuel read the signs. He moved to his right just as the rifle roared. A clean miss. Samuel dived for the ground, rolled to the shelter of a mesquite bush, and then scrambled to his feet. He raised his Colt to eye level with both hands, sighted for an instant, and fired.

The bushwhacker took the bullet high in his chest. Blood staining his mouth, he tossed the Winchester away, signaling that he was out of it. The man was a back-shooter who lacked sand and bottom, and now, hurt bad, he wanted no part of Samuel O’Brien.

The would-be killer hunkered down, and when Samuel came close enough, he said, “I’m done, mister. I’m done for good. Hell, I’m leaving . . .”

“Who paid you to dry-gulch me?” Samuel said. “Damn you, tell me.”

But he realized he was looking into the stiff face and distant eyes of a dead man.

Samuel studied the dry gulcher. He was small, thin, with the haggard look of someone who’d gone hungry as a child. His entire outfit, a ragged high-button suit a size too big for him, black bowler hat, and scuffed, elastic-sided boots, was worth maybe a dollar, if that. But the Winchester was almost new, a model of 1886 in .45–.70 caliber. The rifle cost around twenty-one dollars, or an ounce of gold, more than this bushwhacker could ever have afforded.

Samuel O’Brien reloaded his revolver, but his mind was elsewhere.

Somebody had hired this man to kill him, and that somebody had supplied the murder weapon.

But who? And why?

He had questions without answers.

He didn’t know whom, but he was certai. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...