- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

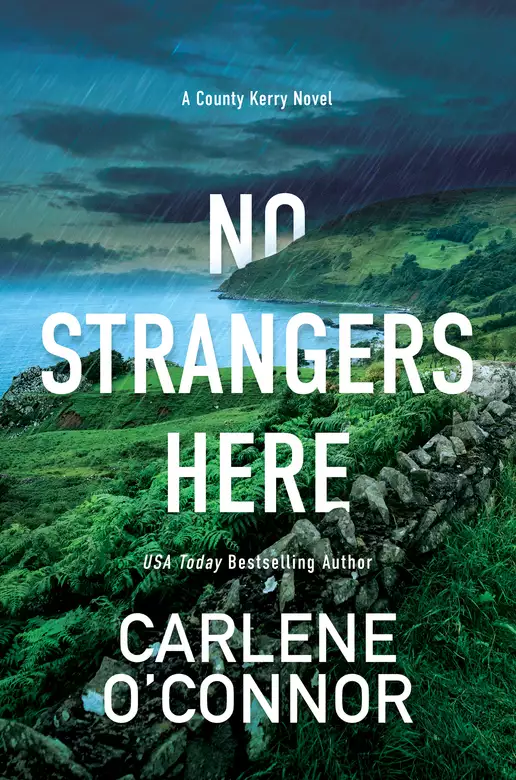

Set in the striking, rugged countryside of County Kerry, bestselling author Carlene O’Connor’s intriguing new series introduces Dimpna Wilde, an Irish vet grappling with life, death, family dynamics, and the secrets at the heart of this small community …

On a rocky beach in the southwest of Ireland, the body of Jimmy O’Reilly, sixty-nine years old and dressed in a suit and his dancing shoes, is propped on a boulder, staring sightlessly out to sea. A cryptic message is spelled out next to the body with sixty-nine polished black

stones and a discarded vial of deadly veterinarian medication lies nearby. Jimmy was a wealthy racehorse owner, known far and wide as The Dancing Man. In a town like Dingle, everyone knows a little something about everyone else. But dig a bit deeper, and there’s

always much more to find. And when Detective Inspector Cormac O’Brien is dispatched out of Killarney to lead the murder inquiry, he’s determined to unearth every last buried secret.

Dimpna Wilde hasn’t been home in years. As picturesque as Dingle may be for tourists in search of their roots and the perfect jumper, to her it means family drama and personal complications. In fairness, Dublin hasn’t worked out quite as she hoped either. Faced with a

triple bombshell—her mother rumored to be in a relationship with Jimmy, her father’s dementia is escalating, and her brother is avoiding her calls—Dimpna moves back to clear her family of suspicion.

Despite plenty of other suspects, the guards are crawling over the Wildes. But the horse business can be a brutal one, and as Dimpna becomes more involved with her old acquaintances and haunts, the depth of lingering grudges becomes clear. Theft, extortion,

jealousy, and greed. As Dimpna takes over the family practice, she’s in a race with the detective inspector to uncover the dark, twisting truth, no matter how close to home it strikes …

Release date: October 25, 2022

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

No Strangers Here

Carlene O'Connor

She placed the palm of her hand on the dolphin’s bronze head, wishing it was slick and gray, wishing Fungie was still with them, wondering if he was out there all alone, chirping into the depths of the ocean, fighting his way back to her. Fungie had been the town dolphin for more than thirty years. Saoirse couldn’t imagine ever being that old. Her mam said he had gone off to die, that it was nature’s way. Nature could stuff it. She wanted him back.

After a gloomy spring, when folks either wrestled with brellies twisting in the wind, or darted in and out of the colorful shops, pubs, and restaurants, cloaked in hooded raincoats, a warm start to June was breathing life back into her harbor town. Strand Street teemed with revelers and mourners. A dance for old people was being held at one end of the street, and a wake for a dead mammy at the other. Irish music spilled out from the pubs competing with the one-man-band-slash-puppeteer camped in front of the statue. He was a scraggly bearded man manipulating a harmonica, drum, banjo, cymbal, and three slack-jawed puppets. With their pale wooden faces, frozen eyes, and gaping red mouths, they looked like miniature corpses being forced to hop up and down just to entertain the living. She knew how they felt. Controlled. Unhappy. Forgotten. Like the dead people who got embalmed so living people could drape over their caskets and wax on about how beautiful they looked now that they were dead. Saoirse would never understand adults. She still couldn’t decide what she wanted to happen to her body when she died and sometimes it kept her up late into the night. She wondered if the dead mammy was going to be embalmed or sunburned.

Soon, tourists encircled the puppet-man, euro clutched in their foolish hands. It would do no good to try and nick any of his tips. She’d done that once and he was faster than he looked. He had chased her all the way down to the harbor, forcing her to drop ten euro even though she had only taken five, just so she could get away. Angry bruises had sported on the back of her arm where he’d grabbed her, and they took forever to fade away. Eejit. She turned her head, feasting her eyes in the other direction. Finally, Saoirse was going to have a birthday party, and who cared if no one else knew it. She was happy out pretending all the fuss was just for her. She was officially a teenager.

She would prove her mammy wrong; thirteen was not an unlucky number and celebrating it wasn’t “asking for trouble.” They were better off, her mother said, celebrating it next weekend when she was thirteen and one week. But next weekend wasn’t her birthday. It was now. Tonight. A Saturday to boot. And even if it was asking for trouble, she’d pick that over another night watching Mrs. Brown’s Boys and eating beans straight out of the can. Gross. Saoirse had nicked a full bottle of Irish Cream, which she’d then left at their door with a bow, and she didn’t even have to sneak out of the house. An hour later, her mammy was flat-out on the sofa, snoring as the telly prattled on, the empty bottle tipped sideways on the floor.

She lingered at the end of the street, surveying her options, and there were three. Option One: Cross the street to the harbor and pick a boat. So many choices! Not just dirty old trawlers, where fishermen left crumpled bills and half-smoked fags lying about in heaps, but sailboats, and speedboats, and the odd fancy one, like the medium-sized white one she’d been keeping her eye on: Dreamscape.

Some of them kept their hatches locked stingy-tight, but there were always a few that yawned opened at her touch. Saoirse was a strong swimmer, and a mad climber. Should she start with the boats, or leave them for the end? Tonight was also the first Saturday in June which meant Option Two: The old people would be dancing. It was so easy to slip a hand into their suit pockets as they shuffled around to trad music, leaving their treasures behind on ring-marked tables. And today, the trifecta. There was Option Three: The dead mammy’s fundraiser.

Cancer had taken her “way too young” and they were collecting money for the three children and husband she’d left behind. No one had held a fundraiser when Saoirse’s father had been carted off to jail and charged with a “domestic”—and Saoirse wasn’t quite sure what that even meant. Why didn’t they just say it was for getting drunk and being mean? He really was mean when he was drunk. Would jail make him nicer? Doubtful. Because right now, things were worse than when he was around. Now they had no money and her mam was sad all the time. Like all the time. And nobody gave a fart about it. How was that fair? Their house had been egged three nights in a row. Maybe Saoirse all by herself wasn’t worth it; maybe she was supposed to scrub up and put on a dress, or maybe she needed cute brothers and sisters. Or maybe her mammy needed to get cancer, or maybe people only cared about you if you were dead.

After agonizing over her choices, she had finally come to a decision. It was her birthday; she would hit them all, starting with the dance and ending on the fancy white boat. Think of all the prezzies she’d collect! Maybe she’d even spend the night on the boat, letting the waves rock her to sleep. She’d keep nicking things until her purple backpack was stuffed. No one would notice her. No one ever did. The head-shrinker she’d been forced to see after Detective Byrne had nearly killed her father with his fists, leaving him in a bloody heap in their garden, taught her that adversity could be an adversary. You could take a negative and make it positive. She was an invisible girl who nicked things.

Coins from pockets and cubbyholes, lipstick from handbags and bathroom cabinets, fags from tabletops—she could make one sweep through a pub after happy hour, and by the time she’d reached the back door, her pockets would be overflowing. Drunk people were such eejits, although now that she was thirteen, she was determined she was going to have her first taste of drink. She was a troublemaker, like her da.

But after the bullies, after those taunts, she’d turned it around just like the head-doctor taught her. Ser-sha, ser-sha, watcha searching for? Tonight she was searching for birthday presents. She wondered if that detective was here, somewhere in the crowd. Was he shaking his hips or comforting motherless children at the wake? He’d probably forgotten all about her. She was supposed to call him Mr. Byrne now; he was no longer a detective because of nearly killing her father. Maybe if he knew it was her birthday, he would have thrown a party for her. She had a feeling he wouldn’t approve of her shenanigans, but who cared? He was no longer a detective. If he didn’t follow the law, why should she?

She was about to slip into the pub where the gray-hairs danced, when she stole another glance at Dreamscape. A person was exiting the fancy white boat, dressed all in black with a hat. Was it another street performer? Or someone famous? Was he so famous he didn’t want to be recognized? Imagine if she nicked something off a celebrity. That would be a dream come true. She decided the mysterious figure was a man, although it was hard to tell, the coat was so baggy. His hands were shoved in his pockets, and face down so all she could see was the top of his dark cap. He was striding away from the boat now, headed for Strand Street. This was her chance. He was wearing mourning clothing; no doubt his destination was the wake. He’d probably be away from the boat for hours. She hurried across the street to the harbor, keeping her eyes trained on the man in black as they switched sides, craning her head and watching him until he disappeared into the crowd. Dreamscape. What a perfect name. Sneaking onto this fancy boat was going to be a birthday dream come true.

THE DEAD MAN WORE A DESIGNER SUIT TO THE BEACH. HE WAS found along Slea Head Drive, at the base of a small cliff, on Clogher Strand. There he was, early on a Sunday morning in June, reposed against a craggy boulder in his fancy navy suit, starched white shirt, and vibrant green tie. Next to his body, two words had been formed using sixty-nine gleaming black stones: LAST DANCE. The stones popped against the pale sand. It wasn’t a whisper; it was a shout. His legs were straight out in front of him, his hands rested palms-up on his thighs, and his sky-blue eyes were open, forever staring out to sea. The only visible sign of distress was the white foam pooling at the corners of his gaped mouth. The lines fanning out across his face, and wisps of silver hair clinging to a mostly bald head betrayed his advanced age. A card with a black background peeked out of the dead man’s suit pocket. Detective Inspector Cormac O’Brien maneuvered around the cordon they’d placed around the body to get a closer look.

A red-faced Devil sporting a lascivious grin stared back. “Would you look at this?” He turned to Detective Sergeant Neely, but her face was buried in her iPad, and her honey-colored hair, whipped around by the wind, obscured her eyes. He was the new sheriff in town, as they said in the black-and-white films he loved to watch, and, despite being by-the-book polite, the rest of the team seemed on a mission to wall him out. Swallowing his frustration and resisting the urge to yank the electronic yoke from her hands and chuck it into the sea, Cormac turned back to the strange card. He was dying to pluck it out of the dead man’s pocket, but Cormac could not touch the body or any of the tantalizing evidence. The state pathologist had been notified, and a local coroner, deputy state pathologist, and technical unit were on the way. Once it was officially declared a crime scene and processed for evidence, they would transport the body to Kerry General Hospital and, fingers and toes crossed, the postmortem would begin in the morning. They already had an identification on their victim, for this was Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland, and the man was a local.

Cormac once again turned to Sergeant Neely, the only member of the Dingle Gardaí he’d allowed to remain with him on the small curved beach. Although she was no doubt used to being the one in charge, she was giving Cormac room, letting him do his thing. Not that she had much choice, but Cormac was grateful she wasn’t sending out any territorial vibes, or Cormac would be forced to pull rank. The guards back in Killarney sometimes called Cormac “Napoleon” behind his back, and he didn’t need that business starting up here. The rest of the guards were gathered in the car park, along the road, and perched atop the cliff.

“I want to go over it again.”

This time D.S. Neely heard him, and her head popped up. She was somewhere in her sixties if he had to guess, but she was well-preserved with a lean, strong body. “Right, so.” If she was sick and tired of repeating herself, she had the decency not to show it. Repetition helped Cormac think. “Johnny O’Reilly, sixty-nine years of age, wealthy racehorse owner. The O’Reillys have a massive estate and horse barns just outside of town. Ever hear of Ruby?” D.S. Neely was looking at Cormac as if the answer should be a resounding yes.

“Ruby slippers?” he quipped.

Neely frowned. “What’s that now?”

“Click my heels three times?” He attempted a smile. “No place like home?”

Neely shook her head, a look of exasperation stamped on her face. “She was a beauty of a racehorse, so she was. Ruby was the O’Reillys’ pride and joy. Their first million-pound-purse winner.” Cormac tried to feign interest. It was obvious the sergeant expected him to be impressed. “Her sire was named Last Dance.”

Now she had his attention. “Is that so?” He glanced at the message written in stone and waited for her to offer more. She did not. “Let me guess. Another million-euro-purse-winner?”

She shook her head. “You really don’t know?” The tone of her voice was clear. He was an eejit.

He threw open his arms. “Indulge me.”

“The poor thing was struck dead in a road accident before he could even run his first race.” She paused. “It was all over the news, like.” Her eyes traveled over him as if assessing his worth. “But I suppose you were just a lad in short trousers.”

“What else?” He smiled and tried to sound chipper, which just elicited another frown. He’d been warned about the locals. Friendly, if you kept your distance. She returned to her electronic notes. “In town, Johnny was known for his other proclivities.” She cleared her throat. “Namely dancing and women.”

“I thought he was a married man.”

A look flickered across her face, as if she’d just tasted something foul. “He’s married, alright. Róisín O’Reilly.” She leaned in. “She’ll strike the fear of God into ya, so she will.”

Cormac would get to the widow later. He couldn’t stop staring at those stones. Last Dance. Was it just a euphemism or did it refer to this dead horse? “How long ago was this road accident?”

She lifted her head as she silently counted. “Has to be well over twenty-five years ago. Maybe longer?”

In this case, a cigar was just a cigar and Last Dance just meant last dance. “How well do you know this fisherman?”

“Finbar? I’ve known him all me life.”

They turned their gaze to the cliff where puffs of cigarette smoke hovered over Finbar Malone’s head before dissipating in the crisp air. He looked the part of an old fisherman, with a grizzled white beard and seafaring attire. A tall and sturdy man to boot. You had to be tough to make the ocean your mistress. He’d been the one to find the body, and Cormac found his initial statement odd. He said he’d stopped here to have a smoke in peace before going home to the missus. When he spotted the body, he clambered to the nearest cottage to request a call out to the guards, and this was the odd part—“Because I don’t own a mobile phone.”

As if sensing he was being watched, Finbar looked down and met Cormac’s eyes straight on. The waves had picked up, lapping farther up the shoreline. “A working fisherman without a mobile phone?” That dog don’t hunt. The fisherman was lying. But why would he lie about a mobile phone?

“Perhaps he meant he didn’t have it with him,” Neely said. “Or maybe it wasn’t charged.”

“But that’s not what he said, is it?”

Neely directed her gaze to Finbar Malone. “Finbar Malone is harmless.” She paused. “Sir,” she added emphatically.

Cormac didn’t need the “sir” routine. He didn’t even want to be called Inspector or D.I. O’Brien. He’d rather everyone just call him Cormac, or Mac, and go about their business. Hell, even Napoleon was better than sir. But with this high-profile case, he was going to need all the clout he could get. His gaze returned to the fisherman. He didn’t know why, but he was lying. Regardless, Cormac was grateful that the burly man hadn’t trampled all over Cormac’s murder scene in his clunky boots. His thoughts returned to Finbar’s first words when Cormac had arrived on scene. Shock of me life, I’m telling ye. On the beach in a suit? Dead as a doornail. I wasn’t expecting that, now.

What had he been expecting?

Cormac had been a member of An Garda Siochána going on nineteen years now, and an inspector for three. Stationed out of Killarney, he was an outsider in this close-knit Dingle community. This was his first murder probe, and given the victim was one of the “elite,” he was going to have multiple sets of eyes on him, a collective hot breath on his neck. There would be no room for error.

Too treacherous to swim, this tucked-away beach was a popular spot for social media photos. Dramatic waves, a curved white beach abutting a rocky cliff, a patchwork of green and brown mountains rising up to the sky—it was Insta-worthy, as the kids said. Cormac, at thirty-nine, felt too old to be in the Insta-anything crowd, and too young to be with the old-timers. But right now, planted in front of this fascinating scene, he felt he was at the beginning of what could be the murder inquiry of the century. Certainly of his lifetime. Cormac was having trouble reconciling the jaw-dropping scenery with the bizarre scene in front of him. The stones fascinated him. Every one of them had been coated with a clear gloss and was nearly identical in size. “Sixty-nine stones.”

“You counted them?” From the tone of her voice such a thing would have never occurred to Neely.

“I did. And yer man here was sixty-nine years of age.”

“Isn’t that something,” Sergeant Neely said, but she looked at Cormac as she said it.

The stones had not all been sourced from this beach, at least not at the last minute. Finding ones nearly identical in size would have taken a tremendous amount of time and effort. And then their killer had painted them, ensuring that when the sun kissed them, they would sparkle.

The gloss was a small clue, but it was at least a thread to pull on. Even cunning killers were human. And humans were gloriously imperfect. Painted stones and a posed body ruled out suicide, something he’d already heard guards begin to utter under their breath. No way was this an elaborate suicide. Although . . . if one were to choose an absolutely gorgeous place to die, it didn’t get much better than this. Mountains and cliffs that drew one’s eyes up to the skies, Slea Head Drive curving through, and the great Atlantic roaring below. If God was an artist, then the Dingle Peninsula was his masterpiece. But why pose the body here? Did this exact location have significance to the killer?

“The waves are advancing,” Neely said in alarm, pointing. Her yellow visibility vest flapped in the wind, distracting Cormac, making him think of the poet Seamus Heaney and how he’d once described the weather in Dingle as “loud.” It took Cormac a moment to see what had agitated Neely. Frothy waves licked at the soles of the dead man’s leather shoes. “Shit. See if we can get some kind of plastic barrier,” he said. “Something to toss over them.”

“I mentioned that ages ago,” Neely said under her breath as she hurried back toward the car park, holding her iPad aloft and carefully following the shoreline. Had she? He’d been lost in thought, no doubt. His ability to shut everything else out while concentrating was both a blessing and a curse. He supposed there was no getting through this investigation without ruffling some feathers. He’d been trying his hardest to bond with them, but they were going to have to meet him halfway. He was here to solve a murder, not make friends, although truth be told, he was a friendly sort by nature. His mam always said he could talk the hind leg off a horse. Cormac stared into the dead man’s lifeless blue eyes. He had a feeling he’d be seeing them in his dreams the rest of his life.

“Who did this to you?” Above, a helicopter whirred, and Cormac could feel the thwack thwack thwack in his chest. Out on the sea the Irish Coast Guard churned, directing boats away from the inlet. A buzz of excitement hung in the air, mingling with cigarette smoke and that distinct ocean tang. Seagulls screeched above, as if they too were glued to the drama. Despite the wind, it was a bright morning, blue sky smiling down at them, but ominous clouds hung in the periphery like actors gearing up for a dramatic entrance. Sergeant Neely returned, clutching a clear plastic cover with gloved hands. She and Cormac tucked it over the dead man’s shoes and around the sides of his legs. Alongside the body, a rocky finger extended from the cliff, and something black and small flapped in the wind. Cormac leaned in. “There’s a piece of black fabric caught on the rock,” he said.

“Clothing?” she asked.

“No.” He removed a pair of tweezers from his pocket. “Evidence bag?”

She reached into the plastic bin they’d set up on the shoreline and handed him one. He lifted the piece of fabric and examined it up close. “It’s not a rubbish bag. It looks like some kind of a tarp.” He hesitated. “Like a body bag.”

“A body bag?”

His eyes traveled over the body. “Could be he was brought here in a body bag.” Did their killer work for law enforcement? The morgue?

“Based on this?” Neely jiggled the evidence bag as he dropped the shard into it. She drew it close and stared at it. “Bit of a stretch, don’t ya think?”

“It would explain how he was brought up to the beach in a boat, and yet he’s not wet,” Cormac said. Apart from his shoes, the dead man was dry as a bone.

“Perhaps he’s just had time to dry,” she said. “The wind alone could have done the trick.”

“Inspector,” a guard on the other side of beach yelled. “We have footprints.”

Sticking to the shoreline, Cormac and D.S. Neely crossed to the base of the hill. There, on the incline, small indentations could be seen ascending the muddy hill. “Jesus,” Neely said. “It’s a young one.”

“Maybe a kid found the body first,” the guard said. “Scrambled away out of fear.”

Cormac examined the prints. “They’re only going up.”

The guard frowned. “What?”

“If a kid found the body, we would see prints going both ways.” He gestured as he spoke. “The prints are only going up.”

“Then where did the kid come from?” the guard asked.

“A boat,” Cormac said. All heads turned to the waves pounding the shore as they pondered this. “Let’s cordon this hillside off so the technical team can get impressions.” The guard nodded. “Check for more prints, and any signs of disturbances at the top of the hill.”

“Right away.” The guard scrambled back up and soon the rest were efficiently conducting a search. “We have more,” the guard yelled back. “The kid at least made it to the top of the hill.”

“I want impressions of all of them,” Cormac said.

“What are you doing?” Neely said. “You can see that this is a suicide, can you not?”

“Suicide?” he said. “No.” He understood why she wanted to label it thus. A suicide would mean this case was closed. Nothing to fear. Dingle was a place for Irish music, a pint or twelve, and the best seafood chowder in the country. A place for water sports and boating. Quaint and colorful little shops. Murphy’s Ice Cream. An outdoor museum of ancient architecture. Ferries to the Blasket Islands. Wine imported from Spain. Downtown even had a small, yet he had to admit, charming aquarium. Fish didn’t set off his allergies; he could do fish. Irish was spoken everywhere you turned, and every sign included the Irish translation. This was the Gaeltacht region, the Wild Atlantic Way, the thirty-mile-long Dingle Peninsula. Ryan’s Daughter . . . Wasn’t that filmed here? Yes, that’s right, bragging rights. It was bad enough that Fungie the Dolphin had disappeared. Murder wasn’t anywhere in the tourist brochures.

Cormac headed back along the shoreline and Neely followed. They stopped when they reached their original spot near the body. “Make the argument for suicide.”

Neely pointed out the vial and syringe they’d found lying on the sand near his hip. Although they couldn’t touch it, they had zeroed in on the vial with a camera lens and read the label: RELEASE. The department iPad had informed them it was a euthanasia medication used by veterinarians. “He owned a lot of horses and employed a lot of vets,” she said. “He could have easily gotten ahold of the medication and syringe.” Next, she gestured to the cryptic message in stone. “He also left a note.”

“Does he mean ‘Last Dance’ as in ‘Goodbye, cruel world’?”

“He could be paying homage to his horse too.”

“Why would a wealthy dancing man take his own life in such an extravagant way?” Cormac asked. “Had he ever threatened suicide before?”

Neely took a step forward. “He was stepping out on the wife. My guess? She threatened divorce. He wouldn’t have wanted all that publicity. He was a man of means. This is an elaborate way to go, I’ll give you that, but it’s suicide.”

“He had access to the medication and syringe and left a note,” Cormac repeated. “What else?” If she was going to insist this was suicide, which it was not, she was going to have to give him cold, hard facts.

She glanced around the beach. “There’s no evidence that another person was here.”

“There’s no evidence that he was here either.”

Her frown deepened. “Inspector?”

“Besides ours—do you see any tracks in the sand?”

Her mouth twitched as she took in the beach. “Not a single one.”

“Indeed.” He loathed that they had walked on the crime scene. They were suited up with gloves and booties and had carefully walked along the water’s edge, but he could still see their partial prints marring what had been a pristine stretch of beach. A killer’s canvas. “Any signs of a body being dragged?”

She shook her head. “It’s as if he just materialized on the beach.”

“You think he walked sixteen point six kilometers in the dark with sixty-nine polished stones in his pocket?” He’d clocked the distance from Strand Street in Dingle, where O’Reilly had attended a local dance, to this spot via Slea Head Drive. It was 16.6 kilometers. This man did not walk to his death. “Kills himself yet makes sure not to leave a single footprint on the beach?”

In lieu of an answer, Neely crossed herself. Was he making headway?

“Look at those shoes.” Cormac pointed, and she looked. Not a scuff mark or clump of dirt to be seen. “These are the soles of a man who wanted the world to carry him.”

“That was Johnny O’Reilly, alright,” she said. “Unless he was dancing.”

“He didn’t do much dancing last night, unless someone brought him a change of shoes.” The smooth beach reminded him of the allegorical poem, “Footprints in the Sand.” Where your man complains that through all his many troubles God had abandoned him for there were only one set of footprints in the sand. But God is quick to correct him. Cormac’s mind raced to the last line: It was then that I carried you. He looked again at Johnny O’Reilly. Who carried you? Cormac took a moment to study the craggy boulder serving as Johnny’s headrest. Nature’s La-Z-Boy. The long rocky finger extended from the base and disappeared into the ocean. Cormac tilted his head back to have a gawp at the cliff hanging above them. “If this was suicide, why didn’t he just jump off the cliff and disappear into the ocean?”

“If it was murder, why didn’t the killer just toss him into the ocean?” Neely responded.

“Touché.” Because then we would miss the show. “Our killer came up by boat. O’Reilly here was in a body bag. He dragged him up this rocky finger, and lucky for us he did.”

“Lucky?”

“The body bag ripped.”

“Right.” Not that Cormac was holding on to much hope that the small piece of ripped bag would lead them to the killer, but it did suggest mistakes had been made. He pointed this out to Neely. “Mistakes?” Neely still sounded guarded, but he had moved the needle just a little, he could tell.

“Mistakes like ripped fabric and failing to notice a young stowaway.”

“It would have to be a small boat to maneuver up to this inlet,” Neely said.

Cormac nodded. “I think a larger boat was waiting out in the ocean. I think the killer used a life raft, some kind of smaller boat, to bring the body in close. And I think the boat had a stowaway. I’m guessing a young lad.”

Neely whistled. “You think the stowaway made a swim for it?”

Cormac nodded. “While our killer was staging the scene. It probably saved his life.”

Neely said something in Irish and crossed herself once again. Cormac, rusty on his Irish, did not ask for a translation. He thought of his mam and granny, constantly working their rosary beads until blisters formed on the tips of their soft fingers. At the time he thought they were actually communicating directly with God, sending out distress signals in a Morse code of their own making. “We’re definitely looking at a murder scene,” Cormac said. “And this clever killer came to play.”

CORMAC O’BRIEN STRETCHED AS HE LOOKED OUT AT THE FORMIDABLE ocean, wondering if he was the only one who felt overwhelmed by its mass and power. You’re nothing, human. You’ll be long gone, and I’ll still be raging. He glanced at his watch. Half-eleven on a Sunday mor

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...