- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

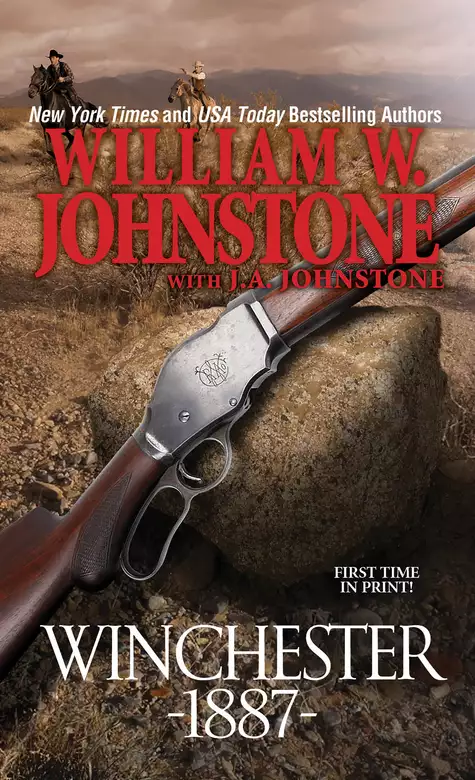

From America's most popular, best-selling Western writer, each novel in this brilliant new series follows the trail of a different gun - each gun with its own fiery story to tell.

On the American frontier, every gun tells a story. A boy in Texas waits for a Christmas present he chose from a Montgomery Ward catalog. The present - a brand-new lever action Winchester 1886 and a box of its big .50-caliber slugs - never makes it there. Instead the rifle is caught up in a train robbery and starts a long and violent journey of its own - from the hands of a notorious, kill-crazy outlaw to an Apache renegade to a hardscrabble rancher and beyond.

But while the prized Winchester is wandering the West - aimed, fired, battered and bartered - Deputy US Marshal Jimmy Mann is hunting for the outlaw who robbed the train in Texas. The only clue he has is this prized and highly coveted weapon. What stands in his way are storms, Indians, thieves, a lot of bloody deaths - and a merciless desperado just waiting to kill the lawman on his trail....

Release date: November 1, 2015

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Winchester 1887

William W. Johnstone

But the lodging came free, compliments of the Fort Worth–Denver City Railroad, although Millard figured he and his family would be moving on before too long. He wasn’t even sure if he would get paid again since the railroad had entered receivership—whatever that was—during the Panic a couple years back, and although it was being reorganized . . . well . . . Millard sighed.

The landscape didn’t look any better than that makeshift home. Bleak and barren was the Texas Panhandle. Rugged, brutal. Sometimes he wished the white men hadn’t driven the Comanches and Kiowas out of it.

His horse snorted. He closed his eyes, trying to summon up the courage he would need to face his family. His wife stood down there, trying to hang clothes on the line that stretched from the boxcar’s grab irons to the corral fence. She fought against that fierce wind, which always blew, hot during the summer, cold during the winter. Out there, the calendar revealed only two seasons, summer and winter, the weather always extreme.

Libbie, his wife, must have sensed him. She turned, lowering a union suit into the basket of clothes and dodging a blue and white striped shirt that slapped at her face with one of its sleeves. Looking up, she shielded her eyes from the sun.

Again, his horse snorted. Millard lowered his hand, which brushed against the stock of the Winchester Model 1886 lever-action rifle in the scabbard. A lump formed in his throat. He grimaced, and once again had to stop the tears that wanted to flood down his beard-stubbled face.

He would not cry. He could not cry. He was too old to cry.

Facing Libbie was one thing. He could do that, could tell her about Jimmy, his kid brother. He could even handle his two youngest children, Kris and Jacob. But facing James? Sighing, Millard muttered a short prayer, and kicked the horse down what passed in those parts for a mesa, leaning back in the saddle and giving the horse plenty of rein to pick its own path down the incline.

He figured Libbie would be smiling, stepping away from the laundry, calling toward the boxcar. Yet Millard couldn’t hear her voice, the wind carrying her words south across the Llano Estacado, Texas’s Staked Plains in the Panhandle. Kris, the girl, and Jacob, the youngest, appeared in the boxcar’s “front” door and then leaped onto the ground.

The horse’s hoofs clopped along. Millard’s face tightened.

Next, James Mann, strapping and good-looking at seventeen years old, stepped into the doorway, left open to allow a breeze through the stifling boxcar.

The sight of his oldest son caused Millard to suck in a deep breath. His heart felt as if a Comanche lance had pierced it. James looked just like his uncle, Millard’s brother, Jimmy. Millard and Libbie had named their firstborn after Millard’s youngest brother. Millard himself was the middle-born. The only son of Wilbur and Lucretia Mann left alive.

His wife’s face lost its joy, its brightness, when Millard rode close enough for her to read his face, and she quickly moved over to stand between Kris and Jacob, putting hands on the children’s shoulders. James had started for him, but also stopped, probably detecting something different, something foreboding, in his father.

“Whoa, boy.” Millard reined in the horse and made himself take a deep breath.

“Hi, Pa!” Kris sang out.

Even that did not boost Millard’s spirits.

“What is it?” his wife asked. “What’s the matter?”

He shot a glance at the sheathed rifle and then lifted his gaze, first at Libbie, but finally finding his oldest son.

Their eyes locked.

Millard dismounted. “It’s Jimmy.”

Jimmy Mann, the youngest of the Mann brothers, had been a deputy U.S. marshal in the Western District of Arkansas including the Indian Nations, the jurisdiction of Judge Isaac Parker, the famous “Hanging Judge” based in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Jimmy had been around thirty-five years old when he had ridden up to the boxcar Millard and his family called home sometime late summer. When was that? Millard could scarcely believe it. Not even a full year ago.

Sitting at the table, he glanced around what they used as the kitchen. It was hard to remember all the particulars, but James had been playing that little kids game with his younger siblings, using the Montgomery Ward & Co. catalog to pick out gifts they would love for Christmas—James doing it to pacify Jacob and Kris. Millard had been on some stretch of the railroad, and Libbie had been in McAdam, a block of buildings and vacant lots that passed for a town and served as a stop on the railroad.

Jimmy, taking a leave from his marshaling job, had found Millard, and they had ridden home together, to surprise the children. James had been interested in a rifle sold by the catalog, a Winchester Model 1886 repeating rifle in .45-70 caliber.

Millard frowned. What was it Jimmy had said in jest? Oh, yeah. “In case y’all get attacked by a herd of dragons . . .” Millard smiled at the memory.

Most rifles out there were .44 caliber or thereabouts. A .45-70 was used in the Army or in old buffalo rifles, and those were single shots. The Winchester ’86 was the first successful repeating rifle strong enough to handle that big a load.

Millard’s weary smile faded. A rifle like that would cost a good sum even considering the discounted prices at Montgomery Ward, but Jimmy had given James a lesson shooting Jimmy’s Winchester ’73 .44-40-caliber carbine. Millard couldn’t understand it, but there had always been a strong bond between James and his uncle. Jimmy had always seen something in Millard’s son that, try as he might, Millard just could not find.

His right hand left his coffee cup and fell against the mule-ear pocket of his trousers and Jimmy’s badge that was inside. His eyes closed as he remembered Jimmy’s dying words back on that hilltop cemetery in Tascosa.

“You’ll give . . . this to . . . James . . . you hear?”

Millard looked again at the beaten-up Winchester ’86. Jimmy’s head was cradled by that sharpshooting cardsharper Shirley Something-or-other. He couldn’t recall her last name, and never quite grasped the relationship between her and his brother. But he knew that rifle. Jimmy had tracked the notorious outlaw Danny Waco across half the West trying to get that rifle. Danny Waco’s lifeless, bloody body lay in a crimson lake just a few feet from Jimmy.

Millard said softly, “I hear you.”

Other men from Tascosa climbed up the hill. Waco and some of his boys had tried robbing the bank, only to get shot to pieces. Jimmy would have—could have—killed Waco in town, but some kid got in the way. Jimmy took a bullet that would have killed the boy, and then went after Waco.

Jimmy killed Waco, but Waco’s bullet killed Jimmy Mann.

Death rattled in Jimmy’s throat. Townspeople and lawmen stopped gawking and gathered around . . . like vultures . . . to watch Jimmy breathe his last.

“Might give . . . him my . . . badge, too.” The end for Jimmy Mann was coming quickly.

Millard didn’t see how his kid brother had even managed to get that far.

“Maybe . . . Millard, you . . .” Jimmy coughed, but once that spell passed, his eyes opened and he said, “Gonna be . . . one . . . cold . . . winter.” He shivered. “Already . . . freezing.”

On that day, the temperature in Tascosa topped ninety degrees. Winter would come, but not for several months.

“You rest, Jimmy,” Millard said. The next words were the hardest he ever spoke. “You deserve a long rest, Brother. You’ve traveled far.”

Millard had learned just how far. From the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory to Kansas, north to Nebraska, into the Dakotas, to Wyoming, New Mexico, and finally in the Texas Panhandle. Chasing Danny Waco and the Winchester ’86 that the outlaw had stolen during a train holdup in Indian Territory.

If only he had ordered that foolish long gun from the catalog, but Jimmy knew how tight money came with Millard. Through his connections in Arkansas and the Indian Nations, Jimmy had promised that he could find a rifle cheaper that even Montgomery Ward offered.

That had brought the oldest Mann brother, Borden, into the mix.

He’d worked for the Adams Express Company, usually traveling on Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad—commonly known as the Katy—trains. In Parsons, Kansas, he had found the rifle, not a .45-70—which Millard thought too much rifle for his son—but a. 50-100-450, one of the first Winchester had produced in that massive caliber.

Jimmy and Borden had decided it would be a fine joke, sending that cannon of a rifle to their nephew. So Borden agreed to take it by rail and have it shipped up to McAdam for James.

It never made it. Danny Waco had robbed the train and killed Borden. Murdered him. With the big rifle.

It was why Jimmy had trailed Danny Waco for so many months, miles, and lives.

Again, Millard thought back to that awful day on that bloody hill in Tascosa.

“He’ll be a better man than me, Millard,” Jimmy said. “Me and . . . you . . . both. Badge and . . . this rifle. You hear?”

“I hear.”

Heard, yes. Millard could hear his brother. But understand him? No, not really.

“That was . . . some . . . journey,” Jimmy said, and then he was gone.

Millard could hear the younger ones, Jacob and Kris, sobbing through the old blankets that separated the kitchen from the children’s bedroom, Libbie trying to comfort them. James sat across the table from Millard, tears streaming down his cheeks. Sad, but his eyes were cold, piercing, frightening. Like Jimmy’s could be when he got riled.

“Where is he?” James said at last.

Millard frowned. “We buried him. In Tascosa.”

“You left him there?” James sprang out of the chair, knocking it over, bracing himself against the table with his hands.

The crying in the children’s room stopped.

“Yes,” was all Millard said.

James swore.

Millard let it pass, no matter how much that language would offend Libbie.

“You told me yourself that Tascosa’s dying, won’t be anything but memories and dust in a year or two. Why did you bury Uncle Jimmy there? Why didn’t you bring him home?”

Because, Millard thought, in a year or two, all that will be left here are memories and dust. “It’s not where a man’s buried. Or how. It’s how he died that matters. More important, it’s how he lived. You’ve got your memories. So have I.”

Reluctantly, he pushed the rifle toward his son. “He wanted you to have this.”

“I don’t want it.” Tears fell harder, and James had to look away, wipe his face, and blow his nose.

“I don’t have any shells for it,” Millard said.

“I don’t want it.” The anger returned. His son whirled.

“I want Uncle Jimmy. I want him alive. You don’t know how it feels. I lost—”

“I feel a lot more pain than you, boy.” Millard came to his feet, only the rickety table separating the two hotheads. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw the curtain move, saw Libbie’s face, the worry in her eyes. He ignored his wife.

“You lost your uncle. I lost Jimmy, my kid brother. I also lost Borden, my big brother. Two brothers. Dead. Murdered. Because of this gun! Because—” He stopped himself, choked back the words that would have cursed him for the rest of his life.

Because you wanted this gun.

He started to sink back into the chair then remembered something else. His hand slid into the pocket and withdrew the badge, a tarnished six-point star. He dropped it on the table, read the black letters stamped into the piece of tin.

“Jimmy wanted you to have this, too,” Millard said. He had to sit. His legs couldn’t support his weight anymore.

James Mann sat, too, after he righted the chair he had knocked over.

Letting out a sigh of relief, Libbie returned to comforting Kris and Jacob.

“The man who killed Uncle Borden—” James began, but stopped.

“Danny Waco,” Millard said numbly. “Rough as a cob, a cold-blooded killer. Posters on him from Texas to Montana, and as far west, probably, as Arizona Territory. He killed Jimmy, too, but Jimmy got him.” Revenge, Millard thought. Was it worth it?

“He took a bullet, Jimmy did, that would’ve killed a kid. Stopped a bank robbery. Stopped Waco. The law’s been trying that for a number of years. Folks in Tascosa, even Amarillo, said Jimmy was a hero. Died a hero.”

The curtain drew open, and Libbie came into the kitchen, her arms around Jacob, a sobbing Kris close behind.

“Maybe,” Kris said, “maybe we can buy a monument—one of those big marble stones—and put it on Uncle Jimmy’s grave.”

“Maybe,” Millard said. Jimmy’s grave had been marked with only a busted-up Winchester, another ’86, that he had used, somehow, to end Danny Waco’s life. Not even a crude wooden cross or his name carved into a piece of siding.

“Put a gun on it,” Jacob said, still sniffling.

“Maybe.” Millard managed a smile.

“A gun on a tombstone?” Kris barked at her brother.

“Uncle Jimmy liked guns!” Jacob snapped back.

“That’s ridiculous,” Kris chided.

“Hush,” Libbie said.

The children obeyed. Millard stared at his oldest son, who sat fingering the badge, his shoulders slumped, at long last accepting the fact that Jimmy Mann was indeed dead, wouldn’t be coming back ever again.

Jacob became interested in the badge and left Libbie’s side. He moved toward his big brother and looked at the piece of tin. “Why’d Uncle Jimmy want you to have this?”

James didn’t answer, probably had not even heard, and Jacob looked at his father for an answer.

“I’m not sure,” Millard said.

“Uncle Jimmy didn’t make James a lawman, did he?” Jacob asked.

Millard tried to smile, but his lips wouldn’t cooperate. His head shook. “No, he couldn’t deputize anyone. At least, not officially.”

“Was Uncle Jimmy a good lawman?” Kris asked.

Millard shrugged. “I reckon. He did it for some time.”

“Can we go see his grave?” Jacob asked.

“Sure. Sometime.” Millard, however, had little interest in seeing the dead. Maybe that was why he left Jimmy in Tascosa. He had not gone to Borden’s funeral, mainly because of the expense and time such a journey to the Midwest would have taken. He had never been to the graves of his parents. Never had he cottoned to the idea of talking over a grave. The dead, he figured, had better things to listen to than the ramblings of some old relation.

James left the boxcar without speaking.

“Where’s Jimmy going?” Jacob asked.

“James,” his sister corrected. “You know he don’t like being called Jimmy. That was Uncle—” She stopped and brushed back a tear.

“But where . . . ?”

“Just for a walk,” Libbie answered with a sigh, stepping toward the open doorway.

Alone with his grief.

Millard felt some relief. His son had walked out with the badge, turned toward the corral. Walking away his troubles, his thoughts. But at least—and this really made Millard feel better—James had left the .50-caliber Winchester ’86 on the table.

An ounce of lead ripped into the hardwood, sending splinters of bark into Jackson Sixpersons’ black slouch hat. The old Cherokee dived to his right just as another slug tore through the air and thudded into a tree. He rolled over and brought up the big shotgun, not lifting his head, not firing, just listening.

Many years earlier—too many to count—he had learned that in gunfights, it wasn’t always the quickest or the surest who survived, but the most patient.

Another bullet sang through the trees.

Sixpersons freed his left hand from the shotgun’s walnut forearm and found his spectacles. He had to adjust them so he could see clearer, but all he saw above him was a blur. “Sweating like a pig,” is how that worthless deputy marshal he partnered with, Malcolm Mallory, would have described it. Idiot white man. Pigs don’t sweat.

He found one end to his silk wild rag and wiped the glasses free of perspiration. His right hand never left the Winchester, and his finger remained on the trigger.

A Model 1887 lever-action shotgun in twelve-gauge, it weighed between six and eight pounds and held five shells that were two and five-eighths inches long (ten-gauge shells were even slightly bigger). The barrel was twenty-two inches. When Sixpersons got it, back in the fall of ’88, the barrel had been ten inches longer, but he had sawed off the unnecessary metal over the gunsmith’s protests that the barrel was Damascus steel. Thirty-two inches was too much barrel for an officer of the U.S. Indian Police and the U.S. Marshals.

“Did you get him, Ned?” a voice called out from the woods.

“I think so. He ain’t movin’ no-how,” came Ned’s foolish reply.

“He was a lawdog, Ned,” the first voice, nasally and high-pitched, cried out. “I see’d the sun reflect off’n his badge, Ned.”

“He’s a dead lawdog now, Bob.”

“Mebbe-so, but you know ’em federal deputies—they don’t travel alone.”

That reminded Sixpersons of his partner. Where in the Sam Hill was Malcolm Mallory?

Footsteps crushed the twigs and pinecones as someone moved away from Sixpersons.

The Cherokee lawman rolled to his knees and pushed himself up. He was tall and lean, had seen more than sixty-one winters, and his hair, now completely gray, fell past his shoulders. His face carried the scars of too many chases, too many fights. He kept telling his wife he would quit one of these days, and she kept telling him as soon as he did, he would die of boredom.

In the Indian Nations, deputy marshals did not die of boredom.

Sixpersons rose and moved through the woods—like a deer, not an old-timer.

Tucked in the southeastern edge of Choctaw land just above the Red River and Texas, that part of the country could be pitilessly hard. The hills were rugged, the ground hard and rocky, and trees, towering pines and thick hardwoods, trapped in the summer heat. The calendar said spring. The weather felt like Hades. He didn’t care for it, but passed that off as his prejudice against Choctaws. Cherokees, being the better people, of course, cared little for loud-mouthed, blowhard Choctaws.

He could hear Ned and Bob lumbering through the thick forest, thorns from all the brambles probably ripping their clothes and their flesh.

Sixpersons figured where they were going, moved over several rods, and ran down the leaves-covered hillside, sliding to a stop and disappearing into another patch of woods. Ten minutes later, he pushed through some saplings and stepped onto the wet rocks that made the banks of the river.

The country was green. Always seemed to be green. The water rippled, reminding him of his thirst, but Jackson Sixpersons would drink later. If he were still alive.

He stepped into the river, the cold water easing his aching feet and calves, soaking his moccasins and blue woolen trousers as he waded across the Mountain Fork. A fish jumped somewhere upstream where the river widened. He had picked the shallowest and shortest part of the river to cross and entered the northeastern side of the woods. He moved through it, heading back downstream, hearing the water begin to flow faster as he moved downhill.

How much time passed, he wasn’t sure, but the water flowed over rocks—running high from recent spring rains—when he dropped to a knee and swung the shotgun’s big barrel toward the other side of the Mountain Fork.

Bob and Ned burst through the forest, fell to their knees, and dropped to their bellies, slurping up the water, splashing their faces, and trying to catch their breath.

Through the leaves and branches, Sixpersons could see the two fugitives clearly. Luck had been with him. Well, those two boys weren’t bright or speedy. He wet his lips, feeling the sweat forming again and rolling down his cheeks.

“C’mon, Bob,” Ned said as he pushed himself to his feet. “This way.”

Sixpersons waited until they were near the big rock in midstream, not quite waist-deep in the cool water. Only then did he step out of the forest and bring the Model 1887’s stock to his right shoulder.

He did not speak. He didn’t have to.

The two men stopped. Their hands fell near their belted six-shooters, but both men froze.

Slim men with long hair in store-bought duds, they had lost their hats in the woods. Their shirts were torn. One of them wore a crucifix, another a beaded necklace. Not white men, but Creek Indians—Cherokees didn’t care much for Creeks, either. Jackson Sixpersons didn’t consider these two men Indians. Not anymore.

They were whiskey runners, selling contraband liquor, some of it practically poison, to Indians, half-breeds, squaw—men, women, even kids. Jackson despised whiskey runners. He had seen what John Barleycorn could do to Cherokees . . . and Creeks . . . and Choctaws . . . and Chickasaws . . . and all Indians in the territories. He recalled all too well that wretched state liquor had often left him in.

He had, of course, been introduced to bourbon. Grew to like it, depend on it, even became a raging drunk for twenty-two years. Until his wife told him that if he didn’t quit drinking, she would pick up that Winchester of his when he passed out next time and blow his head off.

No liquor, not even a nightcap of bourbon, even when he had an aching tooth, had passed his lips since ’89.

Ned and Bob could see the six-pointed deputy U.S. marshal’s badge pinned on Sixpersons’ Cherokee ribbon shirt. Sixpersons figured he didn’t have to tell those two boys anything.

“He can’t kill us both, Bob.” Ned, the taller of the two Creeks, even grinned. “He’s an old man, anyhow. Slower than molasses.”

Jackson Sixpersons could have told Ned and Bob that they would likely get two or three years for running whiskey, maybe another for assaulting a federal lawman, but Judge Parker, being a good sort, did show mercy, and probably would have those sentences run concurrently. It wasn’t like those two faced the gallows.

Instead, he said nothing. He never had been much for talk.

“Reckon he’s blind, too.” Bob grinned a wild-eyed grin.

Silently, Sixpersons cursed Malcolm Mallory for not being there, but waited with silence and patience.

“Die game!” Bob yelled. He clawed for his pistol first.

The shotgun slammed against the Cherokee marshal’s shoulder. His ears rang from the blast of that cannon, but he heard Bob’s scream and ducked, moving to his left, bringing the lever down and up, replacing the fired shell with a fresh load.

Most lawmen in Indian Territory favored double-barrel shotguns, and Jackson Sixpersons couldn’t blame them. There was something terrifying about looking down those big bores of a Greener, Parker, Savage or some other brand. With cut-down barrels, scatterguns sprayed a wide pattern.

Yet that master gun maker, old John Moses Browning—old; he had turned thirty-two in ’87—knew what he was doing when he designed the Model 1887 lever-action shotgun for Winchester Repeating Arms. That humped-back action was original, even compact considering the ’87s came in those big twelve- and ten-gauge models. When the lever was worked, the breechblock rotated at lightning speed down from the chamber. Closing the lever sent the breechblock up and forward, with a lifter feeding the new shell from the tubular magazine and into the chamber. This action also moved the recessed hammer to full cock.

A double-barrel shot. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...