- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The Greatest Western Writer Of The 21st Century

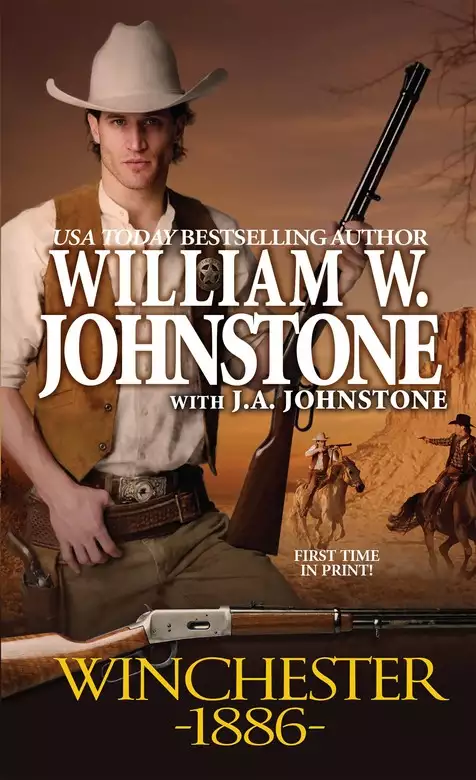

From America's most popular, bestselling Western writer, each novel in this brilliant new series follows the trail of a different gun--each gun with its own fiery story to tell. On the American frontier, every gun tells a story.

A boy in Texas waits for a Christmas present he chose from a Montgomery Ward catalog. The present, a brand new, lever action Winchester 1886 and a box of its big .50-caliber slugs, never makes it there. Instead, the rifle is caught up in a train robbery and starts a long and violent journey of its own--from the hands of a notorious, kill-crazy outlaw to an Apache renegade to a hardscrabble rancher and beyond. But while the prized Winchester is wandering the West--aimed, fired, battered and bartered--Deputy U.S. Marshal Jimmy Mann is hunting for the outlaw who robbed the train in Texas. The only clue he has is this prized and highly coveted weapon. What stands in his way are storms, Indians, thieves, a lot of bloody deaths--and a merciless desperado just waiting to kill the lawman on his trail...

Release date: February 1, 2015

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Winchester 1886

William W. Johnstone

“You’re yeller!” his kid brother Jacob said with a challenging sneer.

Beside him, his twelve-year-old sister dangled the Montgomery Ward & Co. catalog, showing off imported China fruit plates like she was clerking at the mercantile in McAdam, which passed for a town in the Texas Panhandle.

Eight-year-old Jacob lost his sneer. “Please,” he begged.

James Mann stared at him then at Kris, before dropping his gaze to the McGuffey’s Sixth Eclectic Reader. He was making his way through the book for the fourth time, and, honestly, how many times did his ma and pa expect him to read a scene from George Coleman’s The Poor Gentleman? Besides, Ma was shopping in McAdam, and Pa was working on the Fort Worth-Denver City Railroad up around Amarillo. The Potter County seat wasn’t much more than a speck of dust on a map, but Amarillo boasted a bigger population than McAdam.

Since James had finished his chores and had been assigned the grim duty of keeping his younger siblings out of trouble, that child’s game seemed a whole lot more appealing than reading McGuffey’s.

He slammed the book shut, hearing Jacob’s squeal of delight as he slid the Reader across the desktop, and pushed himself to his feet. “No whining when you don’t get what you want!”

Following Kris and Jacob, he pushed his way through the curtain that separated what Ma and Pa called the parlor, and into what they called the dining room. Another curtain separated the winter kitchen, and beyond that lay his parents’ bedroom and finally the room he shared with his brother and sister. All were separated by rugs or blankets that Ma called curtains and Pa called walls.

The Mann home, a long rectangle built with three-inch siding and three-inch roof boards, stretched thirty-four feet one inch long and eight feet, nine inches wide, while the ceiling rose nine feet from the floor. The only heat came from the Windsor steel range in the kitchen. The only air came from the front door, which slid open, and the windows Pa had cut into the northeast corner of the parlor and the southwest corner of Ma and Pa’s bedroom. At one time, the home had hauled railroad supplies from Fort Worth. The wheelbase and carriage had been removed from the boxcar, although the freight’s handbrake wheel and grab irons remained on the outside . . . in case someone needed to climb up on the roof to set the brake and keep the Mann home from blowing away.

Jacob was young enough to still find living in a converted boxcar an adventure. At sixteen, James Mann had outgrown such silly thoughts, although he was about to take part in a game he hadn’t played with Kris and Jacob in years.

The door had been left open to allow a breeze, for the Texas Panhandle turned into a furnace in August, and the nearest shade trees could be found in the Palo Duro country, a hard day’s ride southwest.

Kris and Jacob already sat at the roughhewn table, the thick Montgomery Ward catalog in front of them. James took his seat across from them, giving his younger siblings the advantage. He would be looking at the catalog pages upside down, but, well, he didn’t plan on winning anything. It wasn’t like anything they allegedly won would actually show up on Christmas morning. It was simply a kid’s game.

They called the game “My Page.” Shortly after Ma picked up the winter catalog at the nearest mercantile wherever they were living, the Mann children would sit at the table, and see what they might ask Santa Claus to bring them. They’d open the book, slap a hand on a page, shout out, “My page!” and pick something they might want.

It had worked a lot better, or at least a little fairer, before Jacob had been born, when either Kris or James would actually get a page. By the time Jacob became old enough to play, James figured he had grown too old to play. Besides, his reflexes had always been quick—almost as fast as his namesake uncle’s—so he had left the child’s game to Kris and Jacob. And let them complain and argue and eventually get into a brother-sister fight because Kris had slammed her hand on the page with the Kipling books on purpose, knowing how much Jacob loved Kipling even if Ma was already reading to him.

“You only get five gifts,” Kris explained, “so you better watch what you go for.”

Like anyone really wanted to find a turkey feather duster or whitewash brush under the tree on Christmas Day.

James turned in his seat, looking through the open door at the flat expanse of nothingness that was the Texas Panhandle. Out there, you could see forever, to tomorrow, to the day after tomorrow, to Canada, it felt like. He wanted desperately to light out for himself, but Ma wouldn’t have any of that. She wanted her oldest son to go to college, maybe wind up teaching school. She certainly didn’t want him to wind up in that fading but still wild town called Tascosa, north of Amarillo, and work cattle for thirty a month and found. Nor did she want James to follow in his Uncle Borden’s boot steps, serving as an express agent, risking his life riding the rails with payrolls and letters and such. Borden, the oldest, worked for the Adams Express Company and usually found himself on Missouri-Kansas-Texas trains, but he had gotten James’s father, Millard, the job on the Fort Worth and Denver before Jacob were born.

James could remember little of Wichita Falls, the town near Fort Worth, other than it had been poorly named. It usually had little water to begin with, let alone enough to make a waterfall.

Three years later, the line had stretched out to Harold, just some thirty-four miles. In ’86, when Millard had been promoted to assistant foreman, the line had grown to Chillicothe. A year later, it had reached the Canadian River, and the Manns had made themselves a home out of a boxcar five miles from the town of McAdam. Eventually, the rail line had moved into New Mexico Territory and joined up with the crews laying track from Denver and Millard bossed a crew working on a new spur line.

James would not have minded working for the railroad one bit, even if he had to swing a sixteen-pound sledgehammer in the Texas heat. Yet what he really wanted was to follow his Uncle Jimmy’s line of work. Riding for Judge Isaac Parker’s deputy marshals in Arkansas and the Indian Nations, bringing bad men to justice, seeing some wild country. It sounded a lot more promising, a lot more adventurous, than rocking along in a locked express car as a train sped through the night. It certainly held more promise than bossing a bunch of thick-skulled Irishmen who sweated out the whiskey they had consumed the night before at some hell-on-wheels while lugging two hundred-pound crossties for the rail pullers and gandy dancers.

But there he was, practically a man, babysitting and about to play “My Page.”

“I go first,” Kris said.

“No,” Jacob whined. “I wanna.”

“Too bad.”

“But . . . Ja-aaames!”

Shaking his head, wishing he had stayed in the parlor with his Reader, James refrained from muttering an oath. “Let Jacob go first.”

Kris frowned. “How come?”

“He’s the youngest.”

“You’re just saying that because he’s a boy. Like you.”

“I’m a man,” James declared.

Jacob and Kris giggled, and Jacob pulled the book closer to him. Kris relented, and Jacob opened the catalog. He went deep, probably toward the tables and such, if James remembered correctly, let the pages flutter, and released his hold.

It fell open to two pages of baby carriages. Jacob was ready, hand about to slam down, but he stopped himself from making a critical mistake and risk winding up with a canopy top baby carriage with brushed carpet and matching steel wheels.

No one moved. James was about to slide the catalog toward his sister, when Kris’s hand slammed down on the page without the advertisement in the corner.

“My page!” she yelled.

“You want a baby carriage?” Jacob turned up his nose.

“For my doll.” She pulled the catalog closer, whispering, “Let’s see.” She studied the three rows of offerings, before pointing to one at the bottom corner.

Jacob shook his head, but James pulled the catalog toward him, turned it around, and studied it . . . like old times, when he was a boy. “Twelve dollars and fifty cents?” He smiled.

“It’s silk laced,” Kris said.

“For a doll?” Jacob sighed. “Girls!”

“Well . . .” James slid the catalog back to his sister.

She quickly turned it around, opened it, let some pages fall, and dropped the corner. Capes and cloaks. No one made a move. August came too hot for anyone to think about winter clothing, although they had seen just how harsh Panhandle winters could be.

It was James’s turn. Purposely, he let his pages open to the index.

“Aw, c’mon!” Jacob pulled the book to him. Collars and suspenders. No interest.

Kris’s turn. James saw what he was looking for and made a quick grasp, laughing when Jacob’s hand landed on page 131 as James moved his hand to his hair, and scratched his head.

“My page!” Jacob shouted. He lifted his hand, realizing where his hand had dropped. “Dang it!” He glared at his brother. “That’s not fair.”

Kris was laughing so hard, tears formed in her eyes. “What are you going to ask for, Jacob, the rose sprays or the straw hats?”

“But them is girls hats!”

“You’ll look good in that one.” She pointed to one with fancy edges and trimmings. Available in white, ecru, brown, navy blue, and cardinal.

“Fine.” Jacob said. “I’ll take the orange blossoms.”

“You getting married?” James asked.

Kris pulled the catalog, opened the pages, let one end fall. James decided he might as well play along, so he wound up asking for a dozen packages of Rochelle salts—which made Jacob feel better.

So the game went. Jacob wound up with a Waltham watch, and it did not matter to him that Kris said it was a ladies watch. He liked the stars on the hunter’s case, anyway. Kris got a roman charm shaped like a heart with a ruby, pearl, and sapphire. Jacob picked a leather-covered trunk—Sultan according to Montgomery Ward & Co.—He could use it as a fort or place to hide. Kris chose a ladies saddle, just beating Jacob to the page.

“You ain’t even trying!” Jacob complained to James.

“I’m trying,” James protested. “You two are just too fast for me.”

“All you got is some salts.”

“I like salt.”

The next round, James wound up with a Cheviot suit. He opted for the round cornered sack suit in gray plaid made of wool cassimere. He let Jacob beat him to one of the pages of saddles, and exploded in laughter, as did Jacob, when Kris tried to get a piece of wallpaper, thinking it was fancy lace, but the breeze came in strong and flipped the pages to where Kris wound up with a Spanish curb bit.

“You can use it with your saddle,” James told her.

“You just need a horse,” Jacob added.

It was James’s turn. He stood the book up on its spine and just pulled his hands away, watching the catalog pages spread, flutter, and fall. It landed open. Jacob’s hand headed for one of the pages as James saw the muzzle-loading shotguns on one upper page. He spotted the Winchester repeaters on the facing page and couldn’t help himself. His hand shot out, barely landing on the page just ahead of Jacob’s hand, and he heard himself calling out, “My page!”

“Dang it!” Jacob pulled his hand back. “I wanted that rifle!”

“You’re too young to have a rifle,” Kris said.

James withdrew his hand, and stared at where his hand had fallen. He felt guilty, but only slightly. “I’ll let you shoot it,” he offered.

“Which one?” Kris asked, even though she had no use for guns.

James’s finger tapped on the bottom of the page, and Jacob pulled the catalog toward him, leaned forward, and read, “Winchester Repeating Rifles—Model 1886.”

Kris leaned over. “That’s twenty-one dollars,” she sang out. “And you scold me for wanting a twelve dollar baby carriage?”

“That’s the factory price,” James corrected. “The catalog doesn’t charge that much.” He pointed to the second row of numbers. “Fourteen dollars and eighteen cents.” He had been studying that catalog, poring over that page, since Ma had brought the book home from McAdam Mercantile a week ago.

Reaching for the catalog, wanting to see, to dream some more, he thought of what it must be like to hold a rifle like that in his hands. All Pa owned were a Jenks carbine in .54 caliber that his father had carried during the Civil War and a Colt hammerless double-barrel shotgun in twelve gauge. Pa had let him fire the shotgun, even let him go hunting for rabbits and quail, but never the rifle. Pa didn’t own a short gun, but Uncle Jimmy did, preferring the 1873 model Winchester.

“Promise I can shoot it?” Jacob demanded.

James choked off a laugh. He had as much chance of getting a large-caliber repeating rifle at Christmas as Kris had of getting a $12.50 baby carriage for her doll. Besides, she was getting too old to play dolls. And he was too old to play that silly game.

“They’s lots of models.” Jacob put his elbows on the table, chin atop his fingers, and studied the catalog page. Only one illustration but about a dozen typed descriptions. “Which one you want?”

James knew exactly and found himself reaching across the table and pulling the book toward him.

A voice outside startled him. “What are y’all younguns doing?”

Denison

Both barrels of the Wm. Moore & Grey twelve-gauge belched fire and buckshot, filling Lynn’s Variety Saloon with thick white smoke while the explosion and reverberations drowned out the brief cries of the man Danny Waco gunned down, shooting from his hip.

Ducking beneath the smoke, he shifted the shotgun to his left hand, his right quickly reaching across his body to pull the short-barreled Colt from a cross-draw holster. His thumb eared back the hammer, but he did not fire. He didn’t have to. Even through the drifting smoke, he knew that the man he had just shot no longer posed any threat.

He could see where buckshot had punctured a calendar and splintered some siding. A table had been overturned. The dead man had fallen into a chair, the momentum sending it sliding across the floor and slamming against the wall. He had tumbled onto the floor next to the side door through which he had entered the saloon. The chair, however, remained upright, next to another table where a pitcher of beer stood undisturbed. The drummer sitting next to the pitcher looked so pale, Waco figured that the dude would soon drop dead from an apoplexy.

That struck Waco as uproariously funny. Laughing, he lowered the hammer on the Colt and used the barrel to push up the brim of his hat. “That beer ain’t gonna help you none,” he told the drummer, who still did not move. “You need rye.” Waco turned toward the bartender, who likewise stood like a statue, and snapped a finger.

Crossing the floor to the batwing doors, empty shotgun in left hand, loaded Colt in right, Waco leaned against the doors and swung halfway onto the boardwalk.

The lady across the dusty street at Mrs. Wong’s Millinery Company quickly looked away and busied herself, digging in her purse to fetch the key to her business. An old black man stood, broom in hand, in front of the mercantile, and a cowboy had reined in his strawberry roan a few rods from the saloon. Quickly, the waddie turned his horse around and trotted to the Mexican saloon at the edge of town.

Waco’s gaze landed on the marshal’s office. The door remained shut.

Picturing the town law hearing the shotgun blast and freezing in fear, Waco laughed again.

With a fresh shave and haircut and new blue shirt, Danny Waco figured he looked his best. If the lawman lying on the Variety’s floor had been lucky, and things had turned out differently, at least Danny Waco would have made a fine corpse. Better than the lawdog, anyway, who had been hit with both loads of the double-barrel twelve gauge. The deputy still gripped a Smith & Wesson No. 2 in his right hand. Unlike two barrels of double-ought buckshot, a little .32 rimfire would not have ripped a body apart.

A slim man, Waco wore a pinstriped vest of black wool and gray pants stuck into his new boots showing off the cathedral arch stitching. A black porkpie hat set atop his neatly coiffed hair. His blue eyes missed nothing. Nor did his ears.

The chiming of spurs turned his attention back to the smoky saloon. Gil Millican had risen from the table where he and Waco had been sitting, sharing a bottle of Old Overholt with Tonkawa Tom and Mr. Percy Frick. Millican and The Tonk rode with Waco. Mr. Percy Frick had a job two stops down from Denison working for the Katy, which was what everyone called the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad.

The Tonk glanced at Frick, whose mouth hung open, drawing flies, and whose face seemed frozen in shock. Shaking his head in contempt, The Tonk joined Millican by the wall, staring at the corpse. At least The Tonk had sense enough to look outside first, before closing the door and nodding at Waco.

“This boy’s a deputy marshal,” Millican drawled.

“I hoped so.” Waco listened to the batwing doors pounding back and forth, back and forth, as he walked back to his table. “That’s how he identified himself, ain’t it? I mean, I’d hate to send a man to meet his maker with a lie on his lips.” He slid into his seat, and grinned at Mr. Frick, who did not notice.

The Tonk whistled, then mumbled, “That’s one tight pattern of buckshot.”

“Yeah!” Triggering the top lever, Waco snapped open the barrels and ejected the shells, tossing them toward the spittoon but missing. Smoke wafted from the barrels. “It’s the lightest shotgun I ever held.” He leaned forward, kissed the barrels, still warm to his lips. “Don’t weigh more ’n five pounds, I guess. Hardly even kicks. And I had double-ought in both barrels.” He held the barrel closer to Mr. Frick, but Mr. Frick saw nothing.

It was a beautiful weapon, and Waco knew all about weapons. His father had been a gunsmith, lauded as one of the best in Fort Worth. His father had taught young Danny all he ever needed to know about guns, about shooting, and hunting. Sometimes, Waco regretted killing his old man.

The Damascus barrels were twenty-eight inches. Waco had considered sawing them down, which would have certainly widened the pattern, but it would have ruined the gun. His late father had preached that one didn’t ruin a piece of art by taking a hacksaw to its barrels, and Waco’s English-made shotgun was indeed a thing of beauty. Prettier than the watch he had taken off his poor old dad. Or even that soiled dove he had known in Caldwell.

The barrels chambered twelve gauge, but the frame seemed to have been originally a twenty gauge, which would explain just how light the shotgun felt in Waco’s hands. He brought the gun closer, admiring the engraved scrollwork, the smoothness of the deep brown barrels, the walnut stock and grip, the swivel eyes for a sling at the bottom of the barrel and stock.

Yes, sir, Danny Waco thought, Wm. Moore & Grey of 43 Old Bond Street sure know how to make a shotgun. It killed mighty fine. If he ever made his way to London, he would look the boys up and compliment them on their artwork.

The shotgun disappeared onto Waco’s lap as he fished a fresh pair of two-and-a-half-inch shells from his vest pocket.

Fingering the twelve-gauge in his lap, Waco turned toward the wall. “You boys gonna just stand there gawking. We’re talking business over here.” He looked back toward the beer-jerker. “And you. Yeah, you. I told you to take that drummer a shot of rye. Have one yourself. It’ll get your blood flowing again.”

When The Tonk and Millican were seated, Waco put the shotgun on the table, reached over, and pried the shot glass from Mr. Frick’s hand. “Mr. Frick,” he said, casually. “Mr. Frick,” he repeated in a placating tone. “Frick!” He tossed the whiskey into the man’s face.

Percy Frick blinked rapidly, caught his breath and turned to face Waco. Rather hesitantly, he looked back at the dead body near the wall. “Y-y-you . . . killed . . . him.”

“That’s right,” Waco said casually, refilling the shot glass. “He came in here, interrupting our conversation.”

Waco slid the glass in front of Frick’s shaking right hand.

“But . . .” Frick seemed to discover the whiskey. He lifted the tumbler, shot down the rye, and coughed.

The Tonk refilled the glass, shooting a grin that Waco ignored.

For a moment, Waco and his men thought Mr. Frick might throw up, but the railroad clerk shot down another two ounces of rye.

“Now . . .” Waco grinned. “Let’s get back to business.”

“You killed him,” Mr. Frick repeated.

“We’ve covered that already, Mr. Frick. Yes. He’s dead. Can’t get any deader.”

“But he was a lawman.”

“Correct. A deputy United States marshal riding for Isaac Parker’s court. Or so he said. But the key word there, Mr. Frick, is was. He was a lawman.” Waco sipped his own rye, careful to not shoot it down. Good rye was hard to come by in a place like Denison. “Now he’s a corpse.”

Frick shuddered. “I didn’t think anybody would get killed.”

“Then you don’t know Danny Waco,” Millican said, and immediately regretted it as Waco’s eyes burned into him. Millican cleared his throat, topped off Frick’s glass, and decided to check the dead lawman for any papers, coin, watches, anything that might come in handy. He had already lifted the Smith & Wesson, which stuck out of the right mule-ear pocket on his checkered trousers.

While Mr. Frick tried to come to grips with what had just happened before his eyes, Waco sighed and looked at the bartender. “Did you recognize the lawman, Charles?” The man hadn’t taken rye to the drummer, but the drummer still hadn’t moved.

The bartender blinked. “No, Danny. I sure didn’t.”

“Are we friends, Charles?” Waco scratched the back of his neck. It always itched after a haircut. Those tonsorial artists used talcum powder like it was whiskey, not wasting any.

“Well . . .” The beer jerker understood. “He just rode into town yesterday evening, Mr. Waco.”

“Looking for me?”

“He didn’t say, Mr. Waco. When he dropped in yesterday, he said he was on his way to Bonham to pick up a prisoner.”

Waco smiled. “Guess the prisoner will have to wait.” He sipped the rye again. “But you didn’t mention him, Charles, when Mr. Frick and the boys and me set down to discuss our business. Didn’t mention that a federal lawdog was hanging around these parts.”

The barkeep frowned and used the bar towel to wipe the sweat beading on his forehead. “Honest, Mr. Waco, I didn’t think he was still in town. I figured he’d lit a shuck for Bonham by this time of day. That’s the truth, Mr. Waco.”

“Mister?” Waco laughed again. “It’s Danny, Charles. We’re friends, aren’t we?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Now take that drummer a shot of rye. Pour the beer over his head if he doesn’t respond.”

The barkeep’s head bobbed. The towel dropped to the floor.

“Only an extradition paper, Danny,” Gil Millican said, holding up some bloodstained papers, which he tossed beside the dead man’s hat. “No warrants that I see.”

“Charles is likely right. He probably slept in this fine hot morning. Spotted us as we come to meet Mr. Frick. Decided to make himself famous by becoming the lucky law who got Danny Waco.” He held u. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...