- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

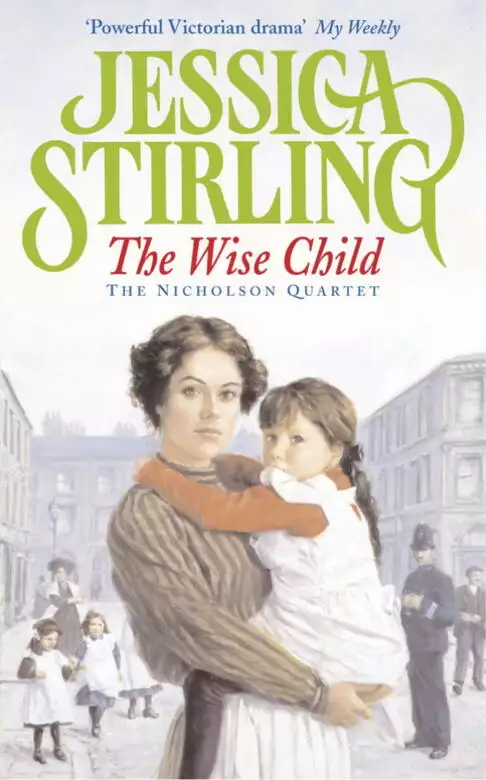

Synopsis

The third poignant novel in The Nicholson Quartet revisits a family divided by pride and weakened by poverty in turn-of-the-century Glasgow. Dedicated to holding their marriage together for the sake of their crippled son, both Kirsty and Craig Nicholson are forced to sacrifice the lovers they have previously found escape in. And for a time all seems well... until Kirsty seizes an opportunity to buy a small shop and makes a roaring success of her new career. Lonely and rejected, Craig continually seeks ways to gain the upper hand on his wife and her partners until only a brittle band of conscience stands between them and ruin.

Release date: January 19, 2012

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Wise Child

Jessica Stirling

of weights and measures, and six policemen. In addition there were a score and a half of that class of citizen disparagingly recorded as ‘dependent relatives’, by which was meant

children and wives.

On the ground floor lived the Boyles, Free Church adherents, who had scrimped and saved to buy their only child, Graham, the benefits of a private education. They were quiet and stand-offish in

contrast to the McAlpines. Constable Andy McAlpine was a rowdy devil given to heavy drinking and, when the mood took him, to punching his wife, Joyce. On the top floor resided the Pipers, a large

family devoted to Gaelic culture who were forever skirling on bagpipes or practising strathspeys to the detriment of the Swanstons’ ceiling below.

The empress of the close occupied the middle landing. Jess Walker’s husband was a sergeant which gave her status as well as an extra six bob a week in the pay packet. In addition she

already had one son in constable’s uniform and three more shined and polished to follow in father’s footsteps. For all her airs and graces Jess Walker was a kindly soul and often looked

after Kirsty Nicholson’s child when no other minder could be found.

The Nicholsons were something of a mystery to the other occupants of the close. The husband was tall, handsome and as dour as sin. He had come into the Police Force by the back door and was

known to be supercilious and ambitious. Kirsty was as different from her husband as chalk is from cheese. She was fresh and obliging, always ready to make the best of things. She’d had a lot

to put up with this past twelve months for the year of 1898 had not been kind to her. She’d had her husband’s family to contend with, then she had lost a baby three months into term and

finally, just as the New Year began, her old friend Nessie Frew had died, though Kirsty, it was said, had come in for a bit of money in the will.

It did not bother Jess Walker that Kirsty was late returning from an errand to St Anne’s church that February afternoon. What did bother her was a distressing rumour that had reached her

through Mrs Swanston who’d had it off John Boyle who had just come off day-shift at Ottawa Street station.

Jess took everything that Eunice Swanston said with a pinch of salt. Nonetheless she was disturbed by the story which did not, for once, seem exaggerated. What made her uncomfortable was that

she had charge of Kirsty’s child, Bobby. Inevitably she would be the first to confront the young woman when she returned from her outing. She was uncertain what to do, what to say, and Jess

Walker was not used to indecision.

She had made a batch of scones and had rolled out an extra length of dough to keep her youngest, Georgie, and Bobby Nicholson amused. Georgie was almost ten now but you never really lost the

urge to play with soft dough and Bobby’s visit provided a grand excuse for childish high jinks and maternal indulgence.

As the afternoon wore into evening Jess became more and more apprehensive. Both her husband and eldest son were on back-shift and would not be home until after ten so that she could not check

with them the validity of Mrs Swanston’s tale. If only Madge Nicholson, Kirsty’s mother-in-law, had still been lodging in Canada Road, Jess might have put the problem into her hands.

But Madge had lately married Albert ‘Breezy’ Adair and, with her younger son and daughter, had moved up in the world. That too had been a source of much gossip in the close and had

caused a serious rift in the Nicholson family for, in Craig’s opinion, Breezy Adair was more crook than businessman.

Kirsty Nicholson’s connection with St Anne’s and the posh folk of Walbrook Street was not held against her by the other police wives. The fact that she could hobnob with her betters

and not seem out of place was a bit of a triumph for a lass who’d been raised in an Ayrshire orphanage and had drudged on a remote hill-farm until Craig Nicholson had run off with her and

brought her to Glasgow several years ago.

Jess Walker was more astute than her neighbours, however. She had sensed in Kirsty’s unhappiness a lack of fulfilment that stemmed from her man’s anger and resentment, from the fact

that he seemed to despise her for the very qualities that other folk found admirable and appealing.

Jess was waiting on the landing when at last Kirsty climbed the stairs. She had Bobby by the hand. He was dusted with flour and had pressed a moustache made of dough to his upper lip. Georgie

Walker was similarly adorned but was more selfconscious about it.

‘See, see, Mammy,’ Bobby cried as soon as his mother appeared.

Kirsty crouched to study her son’s disguise.

‘My, my! What a fine ’tash you’ve grown.’

‘Better’n Daddy’s?’

‘Oh, far better.’

Kirsty glanced up at Jess who, oddly, did not seem to be engaged with the game but looked distant, almost perplexed.

Jess was a small, sturdy woman, heavy-bosomed. Her light-brown hair was flecked with grey. She wore it in a tight roll fastened with three jet combs. Now that the family had two wages coming in

she indulged her taste for floral taffeta dresses and wore one even about the house.

Not to be outdone, Georgie said, ‘How ’bout mine, Mrs Nicholson?’

‘Aye, it’s a cracker too.’

At that moment the moustache became detached from Georgie’s lip and fell with a plop to the stone floor. The boys stared at it, dismayed, then Bobby disengaged his hand from Jess

Walker’s and patted his pal consolingly.

‘Ne’r mind, Georgie. I not got one neither.’ Bobby peeled the dough from his face and flung it to the floor in a gesture of solidarity. ‘See, my ’tash gone

too.’

Kirsty felt a wave of affection for her son. But with it came the first pang of guilt at what she had done that afternoon. She had made love with David Lockhart, an act as distant from

Bobby’s innocent world as China was from Greenfield, yet one, she now realised, that might ruin his little life if ever Craig found out.

‘Georgie,’ Jess Walker snapped. ‘Pick up that stuff this minute. I’m not wantin’ my clean landin’ soiled.’

Schooled in obedience Georgie did as bidden. He knelt and scraped the dough strips from the stone and crumpled them into his fist.

‘What’s wrong, Jess?’ Kirsty lifted her son into her arms. ‘Has Bobby been a nuisance?’

‘No, no. He’s been as good as gold.’

Guilt grew in Kirsty, making her breathless.

‘I’m – I’m sorry I’m so late. I was – detained.’

‘No matter.’

Jess sounded unusually tart. Could Jess have found out what had happened that afternoon in the servant’s room in No. 19 Walbrook Street? Could news have reached Greenfield in less time

than it had taken Kirsty to walk home?

Until that moment Kirsty had felt no regret for what she had done, only a strange sense of relief that David and she had finally been together. It would have been different, of course, if he had

not been leaving for the North China mission field tomorrow morning, if there had not been the hurt of final parting to contend with and the knowledge that, in all probability, they would never

meet again.

‘Somethin’ is wrong, Jess,’ said Kirsty, anxiously. ‘Won’t you tell me?’

Jess shook her head. ‘It’s nothin’ really. Mrs Swanston’s been gettin’ on my nerves again, that’s all.’

‘What’s she been sayin’ this time?’

‘Och, just some daft story.’

‘About – about me, was it?’

‘Some nonsense from the station,’ Jess said. ‘You know how Eunice makes mountains out o’ molehills. I expect Craig might be late home tonight, though.’

‘Another street fight?’

‘Somebody didn’t turn out for muster,’ Jess said. ‘Sergeant Drummond’ll be readin’ them all the riot act, I imagine.’

Kirsty understood only too well how minor disruption to Ottawa Street’s routines could affect not only a husband’s mood but could also throw out of kilter the harmony of the

home.

‘Who was it?’ Kirsty asked.

‘I really couldn’t say,’ Jess Walker told her. ‘Georgie, go inside an’ take the wee pan off the stove. Be careful not to spill it.’

‘Aye, Mam.’

‘I’ll not keep you,’ said Kirsty, taking the hint. ‘I’ll just thank you again for lookin’ after Bobby.’

To Kirsty’s surprise Jess nodded, stepped back into the house and abruptly closed the door.

Kirsty hesitated. She was filled with doubt and apprehension, not about the trivial gossip from the station but in respect of what had taken place at Walbrook Street. It had seemed so natural,

so safe. Tomorrow David would be gone from her life and she’d supposed that she would have no lingering regret about their love-making, only the pain of being without him. Now she was not so

sure.

She shrugged Bobby close against her shoulder and carried him upstairs. He had become long-bodied and heavy of late. He would probably be as tall as his father when his growth was full

gained.

‘Did you have a nice time, son?’

‘Uh-huh.’

She was anxious to be indoors, safely alone in her own kitchen. She was relieved that Craig was on shift and selfish enough to hope that he might be kept late at the station. Tonight of all

nights she did not want him to come to her bed.

In fact it had been weeks since Craig had shown a sexual interest in her. He had been distant and indrawn for most of February, not simmering with rage and frustration, though, as he had been at

New Year, smarting over his mother’s marriage to Breezy Adair and the ‘desertion’ of his sister Lorna and brother Gordon. Wounded pride had hurled him into those black moods but

what had given rise to his recent withdrawn state Kirsty had no idea. She was, however, certain that Craig had not guessed that she had been in love with David Lockhart.

In spite of all that had happened she was still grateful to Craig for having rescued her from servitude on Hawkhead farm. And yet she had fallen in love with David. Now David was gone, summoned

by duty to his family in the China mission, by his calling as a minister.

Once more she was isolated in the tenement suburb with her child and husband. Nothing had really changed because of what she had done that afternoon. She realised now that by her foolishness she

had only compounded the predicament of her common-law marriage.

She unlocked the front door and pushed into the narrow hallway. It was dark in the kitchen, no flicker of fire in the black iron grate. Craig must have left the house early, long before he was

due to report for shift.

Kirsty’s disquiet increased. She set Bobby down and groped across the kitchen to the gas jet by the side of the hearth. Bobby remained by the kitchen door, waiting for light to make the

kitchen friendly again.

‘It’s all right, son,’ Kirsty assured him.

But it was not all right.

Even with the gas lighted the kitchen did not seem like a haven.

She put down the brown paper parcel that David had given her. It contained an old album of photographs of China that had once belonged to Nessie Frew. She took off her coat and flung it across

the bed in the recess. She still reeked of Lily-of-the-Valley. She still wore her best petticoat, her blue garters and the silver pendant that Nessie had given her in happier times. She must take

them off, must hide them away, together with the album. She must wash the scent of perfume from her body before Craig got home. What had happened that day must remain her secret.

She had other secrets too, secrets from the neighbours and secrets from Craig. She had told him that she had received only fifty pounds from Nessie’s estate. In fact it had been two

hundred pounds. She had deposited the balance in an account in a Glasgow bank in her own name; money enough to leave him if it should ever come to that, money enough to pretend that she could

escape.

‘Mammy?’

Bobby was standing by the table. He had stuck a strip of the old dough that Georgie had slipped to him across his upper lip.

‘Gotta new ’tash, see.’

‘My, so you have! That’s amazin’!’

On impulse she picked the child up and seated herself on one of the kitchen chairs, settled him on her knee.

‘Like Daddy?’ Bobby asked.

‘Yes, just like Daddy.’

She hugged him to her breast, rocking gently.

She must not cry, not for the loss of David, not for herself. There was nothing to be done but get on with the life that she had chosen in the hope that it might change for the better.

She sighed, sniffed and kissed Bobby on the brow.

‘Tea time,’ she said. ‘Are you a hungry policeman, Constable Nicholson?’

And Bobby proudly answered, ‘Yes.’

Dusk had settled into the lane that backed Ottawa Street police station. The February day had been clear and mild. Now a prickling white frost rimed the bars and worn stone coping of the

basement window. Head in hands, Craig could hear the familiar sounds of the station clearly but paid them no attention. He remained slumped on the three-legged stool in the bare basement room,

motionless, his back to the door.

Change shift had taken place. Constables gone clumping off into the cold streets. Others had gone hurrying home to supper. Those who were lucky enough to be unmarried would be sitting down to a

piping hot meal in the police barracks around the corner in Edward Road.

Craig waited.

The door of the sergeants’ room slapped open and shut. A desk lid thumped. Voices were raised in laughter and immediately silenced by Sergeant Drummond’s gruff reprimand. From the

lane came the clack of horses’ hoofs. Ordinary sounds, part and parcel of everyday routine. Tonight, however, they seemed edged and menacing, turned inward and downward and pointed against

him.

He had been alone in the holding-cell for what seemed like hours, waiting for something to happen, for somebody to take action. His muscles were tense, his mind fogged, not with alcohol but with

the shock of rejection. Worst of all, he no longer gave a damn what they did to him, even if they booted him off the Force. He wanted them to arrive. He was desperate to get it over with, to be

discarded, punished, dismissed.

He tried not to think of Greta. He tried not to think of her laughter, her derision.

He had offered everything, the sacrifice of his marriage, such as it was, and a fresh start in another part of Scotland. He had shown her the forty pounds that he had signed out of the shared

account. He had assured her that he would be true to her, would cherish her and her child, would never desert or abandon her.

And she had laughed in his face.

She’d asked him if he’d gone loony.

He’d told her he thought she loved him.

She’d laughed again.

He’d taken the banknotes from his pocket and had shaken them in her face and she’d shouted at him not to be so bloody daft, that she’d never run off with another woman’s

husband.

The kitchen had been dappled with afternoon sunlight.

The bairn, Jen, had been seated at the table, eating bread pudding, thick, yellow and studded with raisins. Her cheeks had been smeared with the stuff. She’d been wearing a blue frock with

a lace bib and she’d watched him warily, as if she could see right through him, as if her innocence made her perceptive and wise. He could never bring himself to hate the wee girl but at that

moment he’d come mighty close to it. He’d pulled Greta round to face him.

He’d shouted, ‘What the hell’s wrong with me?’

‘You want too damned much, Craig Nicholson.’

He’d tried to be calm, to explain what was on his mind, the new life, the new beginning.

‘I don’t fancy a new life, not with you, Craig, not with nobody,’ Greta had told him. ‘It’s not me that’s runnin’. It’s you.’

‘What about Jen? Doesn’t she need a father?’

‘The last thing she needs is a father like you.’

Again he’d shouted, ‘What’s wrong with me?’

‘If you’re willin’ to do it once, you might do it again. As soon as you got tired of us, you’d be off.’

‘It’s different wi’ you, Greta. Last time was a mistake. Anyway, Kirsty doesn’t need me.’

‘An’ we do?’

‘I’ve – I’ve taken the money.’

‘Put it back.’

‘Is that it?’ he’d shouted. ‘Is it because you think I’m married?’

‘God, you’ve a right cheek on you, Craig, to assume I’d give up everythin’ for you, married or not.’

‘You gave me plenty in that bed.’

‘It’s what you wanted from me.’

‘You liked it.’

‘I’m not denyin’ it. But that’s no reason to give up my house, my work, my freedom – ’

‘Greta, don’t you understand: I love you.’

‘I doubt it.’

‘What can I say, what can I do to convince you?’

‘Nothin’ will convince me, Craig.’

Jen had giggled then. He’d found her femininity, her archness infuriating. Her dark eyes had seemed coy and full of something instinctive, not learned. He’d been torn between a

desire to pick her up and hug her protectively and a fleeting urge to smash her head against the table.

Sensing danger, Greta had said, ‘Stop it, Jen.’

He’d taken a deep, deep, deep breath.

‘I’ll never ask again, Greta,’ he’d told her.

‘You should never have asked in the first place.’

They had been lovers for almost a year. He had met her in the streets, had been drawn to her gradually. She was all the things that Kirsty was not, or so it seemed. She was perfect for him, a

perfect mistress, shameless, independent, available. But he hadn’t imagined himself to be in love with her until recently.

‘More money, would that do it?’ he’d asked.

‘Not all the bloody money in the world.’

‘Is it the job then? Don’t fret about that. I wouldn’t be a copper any longer.’

‘It’s the best thing you can be,’ she’d told him. ‘It’s the best thing you’ll ever be.’

The child had gone back to her pudding. She’d supped it with a large, long-handled spoon, gripped not in her fingers but in her little fist. Her back had been to him and she’d swung

her legs, rapped her heels on the spar of the chair, blotting him out of her existence and humming contentedly as she did so. That innocent rejection had hurt him more than anything.

No, he mustn’t think of them. He must try to put Greta Taylor and her child out of his mind.

Polished black boots with metal-capped toes tapped on the stone steps; Sergeant Drummond. It hadn’t been Drummond who’d been on the desk when he’d staggered into the station

earlier that afternoon but Sergeant Stevens, a lean, dry man from Islay, who had smelled the whisky on his breath and had yanked him out of the muster and bundled him unceremoniously down into the

basement.

Archie Flynn and Peter Stewart, his pals, had tried to prevent him turning out, had scuffled with him. He’d even had the whisky bottle on him, a conspicuous bulge in his notebook pocket.

He’d told his pals to bugger off and had reeled into the muster room as bold as brass.

‘On your feet, Constable Nicholson.’

For a split second he resisted the command. He could make sure of it right this very minute. He could stand up, swing and punch old Drummond right in the mouth. That would do it. By God, it

would. That would free him from the job, and from all obligations.

‘Do you not hear me?’ Drummond demanded. ‘Are you still so intoxicated that you cannot find your pins?’

Thirty years in Glasgow had not roughened Sergeant Hector Drummond’s lilting Highland accent. He was over fifty now, clean-shaven, crop-haired, portly. He had served all his days in

Greenfield Burgh Police and had witnessed the rise of many a constable and the downfall of many more. He was old now, or nearly so, stoical, efficient and caring. Craig could not bring himself to

strike old Drummond. If it had been Sergeant Stevens things might have been different. But not Drummond.

Craig got to his feet.

‘I am not intoxicated, Sergeant.’

‘Not now, since you have had time to sober yourself.’

From behind his back Drummond produced a half-pint bottle, labelless and nearly empty.

‘Can you deny that this bottle was removed from your person by Sergeant Stevens after you had presented yourself for duty at approximately ten minutes to three o’clock this

afternoon?’ Drummond said.

‘I can’t deny it, Sergeant.’

‘Can you deny that you had been imbibing from said bottle an alcoholic beverage and that you entered the station for duty in a condition that was less than sober?’

‘Slightly less than sober,’ Craig said.

Drummond nodded. ‘Where did you purchase the whisky?’

It was an offence under the Burgh Police Act of 1892 to supply drink to a constable in uniform and carried a penalty of five pounds. Craig realised that he was more recovered than he had thought

himself to be. He answered without hesitation. ‘I bought the bottle last night, Sergeant, when I was in mufti.’

‘Where?’

‘I can’t remember.’

‘Och, don’t lie to me, son. I know shebeen whisky when I see it. You bought this from an illicit source.’

‘No, Sergeant.’

‘Who filled the bottle for you? Was it Jackie Neville, by any chance?’

‘No, Sergeant.’

‘Was it her?’

‘Who?’

‘The woman in Benedict Street with whom you’ve been keepin’ company?’ Drummond said. ‘Did she give you the drink?’

‘What woman in Benedict Street?’

‘Aye, I should have nipped that relationship in the bud a long time ago,’ the sergeant said.

‘There was nothin’ to nip, Sergeant Drummond.’

‘Were you with her this afternoon?’

Craig said nothing.

‘I have to know the truth,’ Drummond said, ‘or I can’t help you.’

‘Yes, I was with her,’ Craig said. ‘But not in the way you mean. I’ve never been with her in that sense.’

‘I have a bit of trouble believin’ that, son.’

‘It’s the truth, Sergeant.’ With a strange sense of separation Craig heard himself say, ‘In case you’ve forgotten, I’ve a lovin’ wife at

home.’

‘Tell me what happened. Tell me why it happened,’ Drummond said. ‘And, most important of all, tell me it will not happen again.’

God, Craig thought, Drummond’s buying the lie. He was going to get away with it after all. He had not had to admit anything, not even that he had bought the whisky from the back window of

Jackie Neville’s house, where the odour of illicit distillation was strong enough to kill rats. He had not had to bow and scrape, swear on his father’s grave that he had done nothing

awfully wrong. All he’d had to do was invoke his loving wife, to conjure up Kirsty as a goddess of humdrum respectability and let sentimentality do the rest.

‘Is it not recorded?’ Craig asked.

‘Aye, of course it’s recorded,’ Drummond answered. ‘Sergeant Stevens is very meticulous, as well you know. He was not well pleased at your truculence.’

‘I – I only had a taste.’

‘How is it then that the bottle is near empty?’

He thought of Greta and how she had spurned him. He thought of her sprawled on the bed, near-naked, and imagined that she had lured him into the affair just to humiliate him, to take revenge on

all that he represented, decency, security, a disciplined society.

‘I took it from her, from the woman in Benedict Street,’ Craig said. ‘You’re right. It is shebeen whisky. She drinks a lot of it.’

‘You should have reported – ’

‘It’s not my beat,’ Craig said. ‘In any case, Greta Taylor’s not the sort you sweep up off the street.’

‘What sort is she?’

Craig shrugged. ‘She has a hard life, Sergeant. The drink’s her only consolation. I worry about the child, though, her child. She’s a holy terror for wanderin’ off, that

bairn.’

‘And you took it upon yourself – ’

‘To keep an eye on her, yes,’ Craig said.

It was easy, so easy to fly on the back of lies.

‘And to share her bottle?’ Drummond raised one grey eyebrow.

‘It was a warm day,’ Craig said. ‘I only had one suck. I never realised that it would be so potent.’

‘Pot whisky has floored better men than you, son,’ Drummond said. ‘How do you feel now?’

‘I’ve a bloody thick head, Sergeant, I can tell you.’

‘So you would have now.’

Craig said, ‘Have you ever – you know?’

‘Once,’ Drummond said. ‘By accident.’

‘I suppose you could say it was an accident, Sergeant,’ Craig went on. ‘Not that that’s an excuse. I know I have t’ take my medicine.’

‘You won’t be dismissed,’ Drummond assured him. ‘Not for a first offence.’

‘You have my word that it’ll never happen again.’

‘And the woman in Benedict Street?’

‘That’s over,’ Craig snapped.

‘Over?’

‘She’ll just have to look out for her own welfare from now on.’

‘John Boyle’ll keep an eye on the child.’

‘Good,’ Craig said. ‘What happens now, Sergeant Drummond?’

‘You go home.’

‘I should be on back-shift.’

‘Not tonight. You go home now and polish your buttons, son. Tomorrow at nine o’clock you report to Lieutenant Strang at Percy Street.’

The sergeant reached behind him and opened the gate. Two pairs of boots vanished from the top of the stairs at the gate’s oily clang. Craig wondered who had been listening to his reprimand

and to his lies. Friends or enemies?

‘You’re not due in court tomorrow, are you?’ Drummond asked.

‘No, Sergeant, not tomorrow.’

‘Nine o’clock, Percy Street,’ Sergeant Drummond said, and, standing to one side, let the chastened young constable precede him upstairs.

Craig’s sudden appearance caught Kirsty off guard. She had not expected him before half-past eleven at the earliest. She jumped from her chair at the table with such a

start that Bobby, who had been feeding himself with two spoons, was frightened and began to wail. Craig had his helmet off and tunic unbuttoned before he entered the kitchen and one glance at his

face filled Kirsty with fear.

The album of photographs that David had given her was still on the bed, together with her garters and frilly petticoat. To Kirsty the air seemed redolent of Lily-of-the-Valley. But Craig paid no

attention to any of these things. He flung his tunic on to the bed, went at once to the sink and twisted the brass tap. He stooped and drank from the flowing jet, swirled water in his mouth and

spat it out into the sink. Bobby continued to wail.

Kirsty said, ‘Craig, what is it?’

She was utterly confused and close to weeping. She went to him and put her hand on his back, felt the muscles under his shirt go tense. He flinched and he shook her off but did not otherwise

acknowledge her presence. He was, she noticed, trembling.

‘Craig, Craig, what is it? Have you been hurt? Are you sick?’

He did not turn around but offered her his shirt collar as if that were an answer. Automatically she took it from him and stared down at it. Craig washed, laving his face and neck with soap,

splashing water everywhere. Bobby climbed down from the chair and, still keening, clung to the back of Kirsty’s skirt.

‘Can you not shut him up?’ Craig snapped.

‘Why are you home so early?’

She handed him a towel as he rose, dripping, from the sink.

‘Ach, you’ll hear soon enough, I suppose,’ he said. ‘I got sent down for bein’ in drink.’

‘Oh!’

She was enormously relieved at the information. She swung away from him to hide it. Craig buried his face in the towel and dried himself vigorously. Kirsty lifted Bobby and walked with him

towards the bed. She lifted the tunic, folded it one-handed and dropped it on the brown paper parcel, drew the curtain over the recess. She turned just in time to catch the towel that Craig threw

to her.

‘Is that all you can say about it?’

‘Was it true? Were you in drink?’ Kirsty said.

‘I had a touch, a taste, that’s all.’

‘Did Drummond smell it on you?’

‘Stevens. He hauled me out the muster.’

‘You haven’t – I mean, you haven’t been dismissed?’

‘Christ, no. One shift, that’s all.’

‘They’ll dock you a week’s pay, though, won’t they?’

Craig peeled his shirt over his head. ‘How do you know so bloody much about it?’

Bobby had quieted. He studied his father now with an expression of belligerent curiosity that was pure Nicholson.

‘Joyce McAlpine told me. It’s happened to Andy more than once. He’s on final warnin’.’ Holding Bobby firmly against her hip Kirsty stretched out and shifted the

kettle on to the hot plate. ‘It could have been worse, I suppose.’

‘Fifteen bob an’ a black mark on my record,’ Craig said. ‘I’ll draw cash out the bank account tomorrow so we’ll not go short. Right?’

It was on the tip of Kirsty’s tongue to remind him that the money in the shared account had been intended as protection against the proverbial rainy day, not to pay for his indulgences.

She kept silent, though, sensing the blackness of his mood.

Craig’s father had been a drunkard, quiet and undemonstrative but hardly ever sober. She had always believed that it was Madge who had driven Bob Nicholson to drink, that the solace of

whisky had become his only escape from her nagging dissatisfaction with the life he had given her. Craig, though, had nothing to escape from, unless

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...