- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

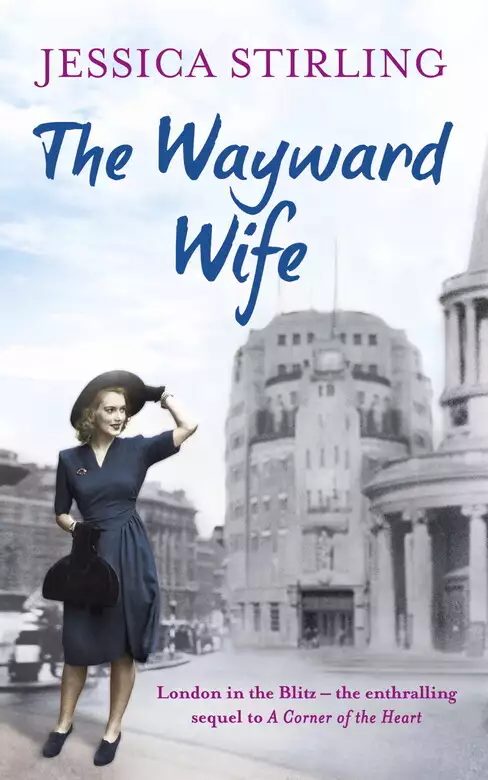

Synopsis

The war everyone dreaded has begun but for Susan Cahill it is an adventure. Helped by a white lie about her marriage to Danny she has a new job as a producer's assistant at the BBC. And glamorous new friends, including one American war reporter who has made Susan his target. Danny is also working for the BBC, working long hours monitoring German radio broadcasts – and worrying about Susan. Stuck in London when the blitz begins, Susan's sister-in-law, Breda Hooper, faces up to the worst with a small son at home and a husband in the fire service. Then her Italian father, hiding from both the authorities and his former partners in crime, prepares to leave Breda an explosive legacy.

Release date: April 11, 2013

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Wayward Wife

Jessica Stirling

It had been a bitterly cold winter so far. The first few weeks of 1940 had brought no respite. Even within the restaurant the air was sufficiently chill to hold a hint of frosty breath mingled with cigarette smoke, a great cloud of which hung over the round table under the skylight where reporters and broadcasters met informally for lunch.

Susan and Vivian were seated at a corner table for two. Vivian had kept on her overcoat and fur hat. Taking a lead from the older woman, Susan too had retained her coat, a tweed swagger, and a pert little hat which, though chic, did nothing to keep her ears warm.

The men who commandeered the round table had checked in their overcoats and scarves and lounged, chatting and laughing, as if they were indifferent to the cold, though one of them, Susan noticed, still sported a battered, sweat-stained fedora that not so long ago would have had him evicted by the management.

‘Well,’ Vivian said, ‘that didn’t take long.’

‘What didn’t take long?’ said Susan.

‘For someone to catch your eye. Who is he?’

‘I’ve absolutely no idea,’ Susan said.

‘They’re Americans, aren’t they?’

‘The boys from CBS, I think. The slim one with his back to us is Edward Murrow, if I’m not mistaken. And that may be Bill Shirer, though I was rather under the impression he was still reporting from Berlin.’

‘And the fellow in the awful hat of whom the maître d’ so clearly disapproves, have you bumped into him in the corridors of power?’ Vivian said. ‘He’s certainly giving you the once-over.’

‘I’d hardly call Broadcasting House the corridors of power,’ said Susan. ‘In any case, if we had met I’m quite sure I’d remember him.’

Vivian sniffed and slid a menu into Susan’s hand.

‘You may have fibbed about your marital status to secure a job with the BBC but it must be all above board now they’ve removed the bar on hiring married women,’ she said. ‘Why don’t you wear your wedding ring?’

‘Because it’s written into my contract that married women will be expected to resign the instant the war’s over.’

‘The war,’ Vivian said, ‘has barely begun. No one’s naïve enough to suppose it’ll be over soon and, if it is, chances are we’ll all be jabbering in German and bowing the knee to Herr Hitler.’

‘I’m sure you wouldn’t mind that too much.’

‘Now, now!’ said Vivian. ‘I may have taken tea with Dr Goebbels and had some of my books published by that Nazi, Martin Teague, but I’ve completely changed my tune since then, as well you know.’

‘My brother, Ronnie, thinks you’re a hypocrite.’

‘At least I stayed in England. I could have fled to the United States like half the literary crowd – well, the fascist half anyway.’

‘Fish,’ Susan said. ‘I do believe I’ll have the fish.’

Vivian peered at the menu. ‘In deference to my new-found patriotism, I will forgo the beef and settle for a mushroom soufflé and the sole meunière. What about wine: a nice dry Riesling?’

‘Patriotism only stretches so far, I see.’

‘We can pretend it’s from Alsace,’ said Vivian.

For the best part of four years Susan had been employed by Vivian Proudfoot to transcribe the controversial books that had earned Viv a degree of notoriety and quite a bit of money but in the spring of 1939, with the possibility of war looming, Vivian had urged Susan to apply for a ‘safe’ job with the BBC.

The interview had been conducted in one of the Corporation’s poky little offices in Duchess Street.

‘Where were you born, Miss Hooper?’

‘Shadwell.’

‘You don’t sound like a person from the East End, if you don’t mind me saying so.’

‘My father felt it would be to my advantage to learn to speak properly.’

‘And your mother?’

‘She died when I was a child.’

‘You were raised by a female relative, I take it?’

‘No, I was raised by my father.’

‘And what does he do? I mean, his profession?’

‘He’s a docker; a crane driver to be precise.’

‘Really? How remarkable!’

The interviewer’s air of superiority had galled her. He was nothing but a middle-aged, middle-rank staffer with a public school accent who clearly disapproved of the gender shift in BBC policy.

‘I see from your application that you were an assistant to Vivian Proudfoot until very recently. Do you share Miss Proudfoot’s political views?’

‘I attended two or three rallies with Miss Proudfoot for the purposes of research. I’m certainly not a supporter of fascism and, may I point out, neither is Miss Proudfoot.’

‘Forgive my caution, Miss Hooper. One can’t be too careful these days. By the bye, I assume you’re not married?’

‘No,’ she’d answered without a blush. ‘No, I’m not married,’ and three weeks later had received a contract of employment.

Unfit for army service and thoroughly unsettled, Danny had lost his job in Fleet Street and been coopted on to the staff of the BBC. From that point on their marriage had deteriorated into sharing a bed occasionally and nodding as they passed on the stairs.

Susan was well aware that the chap in the soiled fedora was interested in her. Hat notwithstanding, he was quite prepossessing in an unruly, un-English sort of way, not all stiff and haughty like so many of the young men she encountered in Broadcasting House. He held her gaze for four or five seconds, then, leaning forward, put a question to the men at his table. They were journalists, foreign correspondents, men of the world and far too polite to look round at her.

Vivian covered her mouth with the edge of the menu.

‘Now see what you’ve done,’ she whispered. ‘He thinks he’s on to a good thing. Oh, God, he’s coming over.’

He was broad-shouldered and heavy-set but walked with a curiously light step, like a boxer or a dancer. He had the decency to take off the fedora and hold it down by his side. His hair needed trimming and the dark stubble on his chin suggested that he hadn’t shaved for days.

Fancifully, Susan imagined he might have stepped off a freighter from Murmansk or, less fancifully, the boat-train from Calais. He certainly had the air of a man who had been places and done things.

She glanced up, gave him the wisp of a smile and waited, a little breathlessly, for him to introduce himself.

‘Miss Proudfoot? Vivian Proudfoot?’

‘Yes,’ Vivian said in her West End voice. ‘I am she.’

‘It’s a real pleasure to meet you,’ he said and, ignoring Susan completely, offered Vivian his hand.

On the few occasions when Susan had persuaded her brother Ronnie to take her up town after dark she’d been intrigued by the massive cream-coloured edifice in Portland Place that looked more like an ocean liner moored in a narrow canal than a building in the heart of London.

She had wondered then at the magic that the wizards cooked up within: dance bands and orchestras, singers, comedians, plays, talks and interviews with famous people all miraculously transmitted to the wireless in the Hoopers’ kitchen in Shadwell. After she’d gone to work in Broadcasting House, though, it hadn’t taken her long to realise that the only magical thing about the organisation was that ‘the voice of the nation’ wasn’t smothered by the avalanche of memos that poured down from the boardroom or drowned out by the bickering that went on between controllers and producers.

Now, with the walls painted drab green to fool German bombers, sandbags piled against the porticos and policemen on guard at every entrance, the seat of national conscience had the same down-at-heel appearance as most of London’s other monumental institutions.

Vivian said, ‘Why the long face? What’s wrong?’

‘Nothing.’

‘It’s not my fault Mr Gaines recognised me.’

‘Gaines? Oh, is that his name?’

‘Do stop sulking, Susan.’

‘I’m not sulking. You’d hardly be full of beans if you were about to spend hours trailing some producer from pillar to post with a notebook in your hand.’

Vivian was a robust woman in her forties and in a military-style overcoat and fur hat had the imposing bearing of a Soviet commissar. She smoked a cigarette in a short amber holder and, with a certain panache, blew smoke skywards. ‘I’m just as surprised as you are that an American newsman was more interested in hearing my opinions than flirting with you.’

‘He was certainly impressed by your latest book.’

‘Oh, that old thing,’ said Vivian. ‘Dashed it off in a couple of weeks when I’d nothing better to do.’

‘Ha-ha,’ said Susan.

‘Ha-ha, indeed,’ said Vivian. ‘We sweated blood on The Great Betrayal, didn’t we, my dear?’

‘Is it selling well?’

‘Better than I expected. Something to be said for cheap paper editions put out for the masses. Handy size for reading in air-raid shelters, apparently.’

‘I’m sorry, Vivian, but I really must go,’ Susan said.

‘Of course.’ Vivian tapped the cigarette from its holder. ‘I must say, you’ve been a model of restraint.’

‘I don’t know what you mean?’

‘Not one question about the rough-hewn Mr Gaines.’

‘I was there. I heard how he flattered you. He seems to regard you as some sort of oracle.’ Susan paused. ‘He certainly had no time for me.’

‘Ah!’ said Viv. ‘There you’re wrong. Unless my old eyes deceive me our Mr Gaines is loitering by the staff entrance even as we speak.’

Susan, with difficulty, did not turn round.

‘What’s he doing there?’ she said.

‘He obviously expected you to have shaken off the boring old battleaxe and is seizing an opportunity to whisper a few sweet nothings in your shell-like without me around,’ Vivian said. ‘He’s a nomad, Susan, a newsman, a stranger in a strange land. He’s probably hoping you’ll take pity on him and show him, shall we say, the sights. It’s your own fault for flirting with him in the first place.’

‘I did not flirt with him, Vivian.’

‘Try telling him that,’ Viv said, then, turning on her heel, headed for Oxford Street and left it to Susan to repair her tarnished reputation as best she could.

When the Welshman touched him Danny Cahill flinched and sat up. It was pitch dark in the bedroom, so dark that the hand that brushed his hair seemed disembodied.

There was nothing remotely sensual in Silwyn Griffiths’s touch. He was merely being careful not to poke a finger into Danny’s eye or up one frozen nostril. As soon as Danny sat up the hand floated away, swallowed by the all-encompassing darkness.

‘What time is it?’ Danny whispered.

‘Ten to six.’

‘What the hell’re you doin’ up so early?’

The stealthy creak of floorboards and a soft little ‘ow’ as Griff barked his shin on the dressing table were followed by the sound of the blackout shutter being raised.

‘It’s crisp out there,’ Griff intoned in the sing-song baritone that Danny hadn’t quite got used to yet. ‘Deep and crisp and even, one might say.’

‘You mean, it’s snowin’ again?’

‘Heavily.’

Danny propped himself up on the pillow.

‘Therefore, no bus,’ he said.

‘No bikes either,’ said Griffiths. ‘We’re on the hoof this morning, boyo, by the look of it.’

He lowered the noisy blackout shutter and switched on a bedside lamp. He was clad in a roll-neck sweater that one of his innumerable girlfriends had knitted for him, and the sheepskin coat his father, a hill farmer in Brecon, had handed down.

Danny had been raised in a Catholic orphanage where cleanliness was next to godliness but the prolonged spell of wintry weather had undermined his principles too. He slept in his underwear and settled for a dab with a damp washcloth in Mrs Pell’s kitchenette in preference to the icy cold of the bathroom on the landing.

Sucking in a breath, he flung aside the bedclothes, reached for his shirt and trousers and dressed quickly.

‘What if we can’t make it, Griff?’

‘The boys on the night shift will stay on. We are, however, obliged to gird our sturdy loins and give it a go. You’re a Scot, for heaven’s sake,’ said Griff. ‘I thought you’d be used to weather like this.’

‘I haven’t set foot in Scotland in years,’ Danny said. ‘Anyroads, I was reared in Glasgow not a bloody Highland croft. Are you ready for breakfast?’

‘I am. Indeed, I am,’ Griff said, and led the way downstairs to the only warm room in the house: the kitchen.

They were billeted in a semi-detached council house in Deaconsfield, a tiny hamlet three miles from the monitoring unit in the grounds of the Wood Norton estate. They were more fortunate than some of their colleagues, for certain members of the rural community were suspicious of, not to say downright hostile towards, the eccentric foreigners that the BBC had dumped on their doorsteps.

The Pells were not of that ilk. Mr Pell was a lanky man with a laconic sense of humour and Mrs Pell, as small and chirpy as a sparrow, wasn’t fazed by her lodgers’ erratic hours and gave good value for her billeting fee when it came to dishing up the required two hot meals a day.

‘My dear lady,’ Griffiths purred, ‘we’d no intention of dragging you from your beauty sleep at this unholy hour. I do hope we didn’t wake you and, if we did, I can only offer my apologies. I say, is that French toast?’

The sight of thick slices of bread dipped in egg and fried to a golden brown made Danny’s stomach rumble. He balanced his plate on the edge of the dresser and attacked the toast with a fork.

‘Fifty-seven below in Finland, Mr Pell tells me,’ Mrs Pell said. ‘Heard it on the news. Even the Russians are dropping like flies, Mr Pell says. You’ll know all about that, I suppose.’

The Pells were aware that Griffiths and Danny helped compile the daily Digest of Foreign Broadcasts, a thirty-thousand-word document dispatched to an ever-growing number of ministries and government departments, and were forever fishing for inside information on the state of the war in Europe, information that Griff and Danny mischievously refused to surrender.

‘Fifty-seven below, eh?’ said Griff. ‘I wonder what sort of reading we have in Deaconsfield this morning. Whatever it is, we’d better get a move on before it gets any worse.’

He picked up the last piece of toast, stuffed it into his mouth and washed it down with tea. He wiped his fingers on the skirts of his coat, fished a knitted woollen cap from his pocket and fitted it snugly over his curly hair.

Danny settled for an old cloth cap.

‘Got your gas masks, both of you?’ Mrs Pell asked.

‘Fully equipped, Mrs P,’ Griff assured her.

‘Will you be home for supper?’

‘Lap of the gods, I’m afraid,’ said Griff. ‘Especially in this weather.’ He unlatched the back door and stepped into the porch.

Drifting snow covered the steps and formed a steep bank against the side of the garden shed. There wasn’t a warden within miles of Deaconsfield but Mrs Pell, taking no chances, swiftly closed the door behind them.

‘God, what a mornin’,’ Danny said, shivering. ‘Be no mail delivered today, I doubt.’

‘And no letters from your lovely wife,’ said Griff and yelped when Danny shoved him out into the snow.

Many of the women who worked in Broadcasting House would have been flattered by Robert Gaines’s attentions, others would have been irritated by his inability to come to the point and one or two shy virgins, fresh up from the country and not yet wise in the ways of the world, would perhaps have viewed him as a serious threat to their maidenhood.

Susan, however, was neither impatient nor virginal and after four years consorting with Vivian’s gang of right-wing toffs and sleazy intellectuals regarded herself as flatter-proof.

Her sister-in-law, Breda, would undoubtedly have forced the issue by throwing herself, bosom first, at Robert Gaines.

Breda had always been attracted to large, bear-like men. In her halcyon days, before Ronnie had knocked her up and had gallantly agreed to marry her, Breda had run up an impressive tally of wrestlers and boxers, not to mention the odd Irish scallywag, all of whom, being the kind of men they were, had ridden off into the sunset as soon as they’d had their way with her. At least, Susan thought wistfully, Breda had had some fun before she’d settled down; her solitary affair had brought nothing but heartache in the end.

No more broken hearts now, she told herself, as she stood before the mirror in the ladies’ cloakroom on the third floor of Broadcasting House and applied a light touch of natural lipstick and an even lighter dusting of face powder to disguise the fatigue that several hours of taking dictation from Mr Basil Willets had laid upon her.

She was no longer the uncultured young girl who’d crept out of Shadwell to work as a temporary secretary to lawyers, doctors and City gents but she was, she supposed, still pretty enough to attract the attention of sensible men now she’d learned to disguise her East End origins.

In fact, she’d left her roots and her family far behind even before she’d stumbled into marriage with kind, caring and utterly dependable Danny Cahill, a marriage that war, and her job with the BBC, threatened to undermine.

Now, with Danny out of sight if not entirely out of mind and every day tainted by uncertainty she was almost, if not quite, ready to throw caution to the winds and embrace the opportunity for a romantic adventure that chance, mere chance, had blown her way.

She put on her overcoat, hat, scarf and woollen gloves and made her way down by the stairs to the main reception area at the front of the building.

No light now, no gleam or glow was allowed to spill out into the street, for Broadcasting House was no longer a beacon to the world. ‘The BBC must set an example,’ the memo had read. ‘It is the responsibility of all staff members to ensure that blackout restrictions are strictly observed.’ Thick layers of dark green paint and metal shutters had taken care of the windows, all the windows on all floors, but the foyer and reception hall had caused problems.

She crossed the gloomy reception hall to the huge, heavily weighted drapes that covered the bronze doorway, curtains stolen, it was said, from the old Hoxton Empire; a rumour that, like so many rumours these days, had turned out to be false. The elderly commissionaire heaved aside the slip curtain and let her enter the muffled passage between the curtains and then, with much flapping, the duty policeman opened the doors and released her on to the pavement.

Half past six o’clock, the cold so keen that it scalded your skin: Susan turned up her coat collar and glanced towards the steps of All Souls Church where Robert Gaines might or might not be waiting.

There was no sign tonight of the American. If she’d been younger and less sure of herself she would have lingered on the pavement in the hope that he might show up but she was no wan little typist desperate for love and, like time and tide, would wait for no man. Besides, she had a gut feeling that Mr Gaines might be playing a game, not to tease but to test her; a novel kind of seduction that she found both irksome and exciting.

Of their three casual encounters in the past week none had led to dinner and dancing but only to coffee and cake in a café off Wigmore Street, surrounded by noisy young nurses and doctors in smart new uniforms, and a half-hour’s guarded conversation in which neither Robert nor she seemed willing to give much away.

Squaring her shoulders, she walked on without breaking step. If he comes, he comes, she thought, and if he doesn’t, well, that’s up to him. He was, after all, a hard-pressed working journalist with deadlines to meet and for all she knew, for all he’d told her, might even now be on a boat heading for France or Italy or even off home to New York.

She had almost convinced herself that she didn’t care when, waving his hat in the air, Robert Gaines appeared out of nowhere and, calling her name, hurried to join her.

‘I thought I’d missed you,’ he said.

‘You almost did,’ said Susan.

‘Coffee,’ he said, ‘or would you rather have a drink?’

‘Coffee,’ she said, ‘will be fine, particularly if you’re pushed for time.’

‘I’m always pushed for time. You know how it is.’

‘Of course,’ Susan said and, taking his arm, accompanied him through the darkened streets to the café just off Wigmore Street to play another cautious game of pussyfoot for the next half-hour or so.

Breda’s mother, Nora Romano, thought that Ronnie in his fireman’s uniform was the handsomest thing on two legs. Lots of women in Shadwell agreed with her. Even the old croakers, who should have known better, simpered a little when Ron strode up Fawley Street with the peak of his cap pulled down to hide the gimlet gaze he’d developed since trading a butcher’s apron for a heavy wool tunic with a double row of chrome buttons.

It wasn’t the old croakers that worried Breda as much as the young chicks who breezed about the East End at the wheel of ambulances or manned telephones in command posts and who, in Breda’s jaundiced opinion, would have the trousers off any feller under the age of seventy who looked as if he might be up for a bit of hanky-panky now that conscription had thinned the ranks of available males, including husbands.

For that reason, among others, Breda had retreated from the school on the Commercial Road where, at the crack of dawn on the last day of August, half the mothers and children in the East End had assembled, complete with gas masks, rucksacks, suitcases and a mournful assortment of dolls and teddy bears, to be herded off to God knows where.

She’d taken one look at the doleful mob and, with Billy clinging to her hand, had turned tail and legged it back to the terraced house in Pitt Street where Ronnie, in vest and drawers, had been seated at the kitchen table bleakly toying with a poached egg.

‘Changed your mind, ’ave you, love?’ he’d said. ‘Can’t say I blame you,’ and that, much to Breda’s relief, had brought an end to all talk of leaving Shadwell.

As penance for remaining in London she was obliged to escort Billy to a school on the far side of Cable Street where in a half-empty classroom the handful of kiddies who’d stayed behind were taught the three Rs by a bad-tempered old spinster. The teacher did not like Billy, Billy did not care for the teacher, and Breda didn’t like anything about the school, particularly the earth-filled sandbags that leaked filthy brown sludge across the playground, sludge that winter had turned to ice.

On that particular morning, she gave her son a kiss, made sure he had tuppence for his dinner and, with the usual twinge of anxiety, watched him join his chums on the slides that criss-crossed the playground. Then, flipping up her coat collar and sticking her hands in her pockets, she set off for Stratton’s Dining Rooms where her mother continued to dish up grub to cabmen and dock workers and, increasingly, to men and women in unfamiliar uniforms who popped in off the street in search of a sandwich or a bowl of soup.

She had barely left the school gate when a long, black, bullet-nosed motorcar prowled up behind her and drew to a halt at the kerb. The nearside door swung open.

‘Get in,’ the driver said.

Clutching her coat to her throat, Breda stepped back.

‘For God’s sake, Breda, will you just get in.’

‘Is ’e with you?’ she asked.

‘Nope. It’s just me. Get in an’ I’ll drive you home.’

‘I ain’t goin’ ’ome.’

‘All right. I’ll drop you wherever you wanna go.’

She had no fear of Steve Millar, her father’s right-hand man. In fact, when Ronnie had been off fighting in Spain, she’d almost given her all to Steve in the back row of a local cinema. She hadn’t clapped eyes on him for a couple of years, though, and was gratified to note that he was still smooth and fresh-faced and so fit you could almost see his muscles rippling under his alpaca overcoat.

She tucked a straggle of bleached blonde hair under her headscarf and then, sighing, climbed into the passenger seat. Steve reached across her lap and closed the door.

‘That Billy?’ he said.

‘Who else would it be?’ said Breda.

‘He’s grown since I saw him last.’

‘Yeah,’ Breda said. ‘He’s gonna be tall, like ’is dad.’

Steve took off his gloves, dug a packet of Player’s from his overcoat pocket, knocked out two cigarettes, lit them and passed one to Breda.

‘I got a kid too,’ he said.

A faint sense of disappointment stirred in Breda, as if fathering a child had robbed Steve Millar of virility.

She said, ‘Boy or girl?’

‘Boy. Cyril.’

‘Cyril?’

‘Rita picked it, not me.’

‘Don’t tell me you married that redhead?’

‘Who said anything about marriage?’

‘Nah.’ Breda blew smoke. ‘You aren’t that sort, Steve. You’ve given over to the old ball an’ chain. Admit it.’

He grinned. ‘Yeah, you’re right. I’m spliced good an’ proper.’

‘Why’d you do it? To keep out of the army?’

‘Havin’ a kid ain’t gonna keep nobody out of the army,’ Steve said, ‘leastways not for long. When things get really nasty we’ll all be fair game for cannon. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...