- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

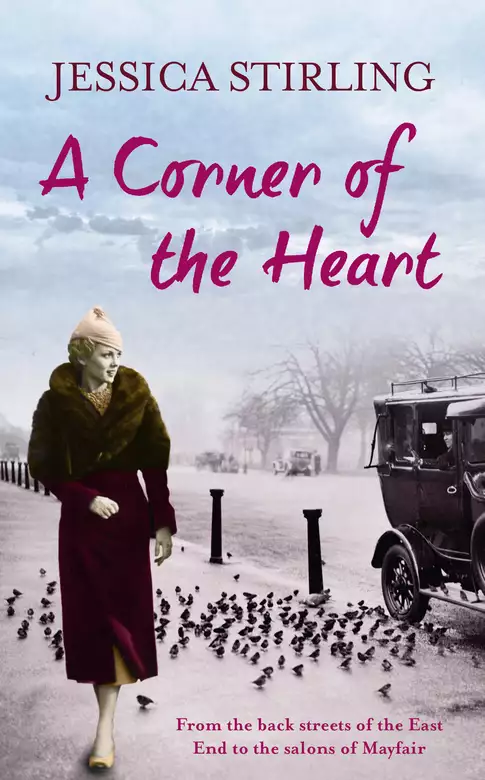

The first novel in Jessica Stirling's enthralling saga series is set in 1930s England, where an East End girl with ideas of her own makes a surprising journey from the back streets of Shadwell to the salons of Mayfair. Susan Hooper is private secretary to bestselling author, Vivian Proudfoot. Well-spoken and well-read, she soon learns how to hold her own with London's literary sophisticates. But the attentions of Mercer Hughes, a handsome agent with a notorious reputation and a shady past, are more than a docker's daughter can cope with and she finds herself falling reluctantly in love. She is soon cut off from her father and at loggerheads with her idealistic brother Ronnie and his gadabout wife Breda. Even her old friend, newspaperman Danny Cahill, is shocked at the circles in which Susan finds herself where pimps and gangsters rub shoulders with wealthy fascist sympathisers in support of the war in Spain. As the threat of world war grows Susan is torn between loyalty to her family and a lover who will not let her go. But when the time comes to choose she finds a solution that surprises everyone. Susan's story continues in The Wayward Wife.

Release date: December 9, 2010

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Corner of the Heart

Jessica Stirling

She watched her father tip open the window in the partition and realised to her dismay that he was about to tell the cabby, a complete stranger, how he’d rescued her from the shackles of poverty. Not that she’d ever been poor, not poor the way she thought of it, not scratching in the gutter poor, not starving to death poor like her grandfather who’d worked the India Docks when the going rate was five pence an hour and you were lucky if you got eight hours continuous a week. To be fair, her dad had good reason to be proud. He’d raised her without any help and when the time came had scraped up the shekels to enrol her at Cowper’s College of Commerce and keep her there even during the dock strike when her brother Ronnie’s skimpy wage was all they’d had to live on.

‘Our Susan,’ her father said, ‘was born with a head on her shoulders. All I ever done was encourage ’er to use it. Make ’er mother proud, she was still alive. Never been flighty, our Susan, not like them young ’uns who get ’anded it on a silver platter. Right?’

‘Right,’ said the cabby obligingly.

‘Ain’t been no cake-walk, I can tell you, raising ’er on me own. But now she’s hobnobbin’ with toffs there’ll be no lookin’ back. Proves it can be done, don’t it?’

‘Right,’ said the cabby, then, ‘What can be done?’

‘Silk purse, sow’s ear: need I say more?’

Susan had heard the phrase so often that it no longer rankled.

Dad had insisted on hiring a cab for the trip across town to Paddington. No daughter of his, he said, was going to stumble out of the Underground all damp and draggled like a workhouse rat. She was leaving for green pastures at last and, by George, he was going to be there to see her off even if it meant sacrificing half a shift and forgoing his eight pence worth of steak and onion pie in Stratton’s Dining Rooms to do it.

‘What education’s for, ain’t it?’ he rattled on. ‘Diplomas, she’s got five of ’em. An’ she speaks proper. Four years that took; four years of Saturday afternoons with Miss Armitage at a half-crown a pop. Can fool anyone if you speaks proper. Saw that in a play, I did, when Susie weren’t much more than a nipper.’ He chuckled. ‘Say somethin’, sweetheart. Give the man a earful of King’s English.’

Miss Armitage had been on the stage at one time and claimed to have acted with Mrs Patrick Campbell when they were girls. Susan didn’t know whether to believe her or not. Miss Armitage didn’t much care for Dad, though that didn’t stop her taking his money and doing her best to plane away the worst excesses of Susan’s cockney twang. Susan, in turn, had kept her end of the bargain and had practised her exercises assiduously at home in front of a mirror, though she’d hidden her new-found vocal mannerisms from everyone at school because she knew they’d only laugh. Later, however, when she’d gone out into the world as a registered stenographer her ability to ‘speak proper’ had landed her the agency’s plum jobs.

She inched forward and in a soft, carrying whisper mischievously recited the first verse of a Christina Rossetti poem that had been one of Miss Armitage’s favourites. ‘“Does the road wind uphill all the way? Yes, to the very end. Will the day’s journey take the whole long day? From morn to night, my friend.”’

‘See,’ her father said smugly. ‘Told yer, didn’t I?’

‘Right,’ said the cabby for the third time and, more irked than impressed, it seemed, reached behind him and snapped the little window shut.

‘What’s biting ’im?’ her father said.

‘It’s been a long day and it’s raining. I expect he’s tired.’

‘Yus, that must be it,’ her father said and, not much mollified, rested his brow against the glass and watched the London landmarks rush past in the gloom.

Vivian Proudfoot waited by the station bookstall. She was a tall woman in the region of forty, unseasonably clad in a hacking jacket, tweed skirt and cable-knit sweater. She looked, Susan thought, more like a member of the Hoxton Ramblers’ Club than a bestselling author. A briefcase rested against her calf and a bulging rucksack was strapped to her back, the weight of which tugged at her shoulders and made her bosom protrude alarmingly.

‘Mr Hooper!’ she trumpeted. ‘I didn’t expect to see you here.’

‘Come up by taxi,’ Matt Hooper said, ‘to wave ’er ladyship off.’

‘Don’t you think a girl of twenty might be capable of waving herself off?’ Miss Proudfoot said. ‘Female emancipation’s all the rage, you know.’

‘Our Susie ain’t never been away from ’ome before,’ her father said. ‘I don’t want ’er to get into no trouble.’

‘Susan will be fine,’ the woman assured him. ‘I’ll take good care of her.’

Then, hoisting up the briefcase and adjusting the straps of her rucksack, she marched off towards the platform, leaving Susan to plant a hasty kiss on her father’s cheek and follow on behind.

The summer sky still held hours of daylight but soot and rain had created an almost wintry murk through which signal lights and early lights in offices and shops blinked wanly as the train pulled out of the station.

Back home, to the east of Aldgate, the gutters ran like rivers and the river itself was the colour of rusty iron. You couldn’t see the river from the terraced house in Pitt Street but on wet nights like this you could smell it. For three years Susan had temped for lawyers, bondsmen and stockbrokers in elegant rooms and panelled chambers but no matter how late she’d returned Dad would be sitting up with a pot of tea and a plate of toast, anxious to hear what she’d been up to. Tonight, with her brother Ronnie out drinking as usual, her dad would be all alone.

‘You’re not sulking, are you?’ Vivian Proudfoot asked.

‘Of course not.’

‘Don’t tell me you’re scared?’

‘Perhaps a little.’

‘We’ll pop along for afternoon tea soon; that’ll perk you up.’

There were three men in the compartment busy reading newspapers and pretending they had no interest in the pretty young thing in the seat by the window.

Miss Proudfoot put a hand on Susan’s knee.

‘You’re not afraid of me, are you?’ she said. ‘It’s not as if we’re strangers.’

‘It’s not you,’ Susan said. ‘I don’t know what it is.’

‘A crisis of confidence would be my guess.’

‘Yes, I suppose you might call it that.’

Miss Proudfoot laughed. ‘Come now, Susan, we’re not lodging with the Astors. My brother and his brood aren’t in the least intimidating.’

‘Do they have servants?’

‘Oh, yes, a few: a cook, a day maid or two and, I dare say, some lad from the village to do the boots; nothing for you to worry about. Now you’ve raised the subject, however, may I remind you that you are not – repeat not – a servant. You are my personal assistant. If anyone orders you to tote luggage or fetch tea you have my permission – nay, my instruction – to tell them to push off and if they come over all high-hat then refer them, whoever they are, to me.’

‘Oh!’

‘Don’t look so stricken, girl. It won’t come to that. There’s an egalitarian streak in my brother that neither Harrow nor the Guards quite eliminated and if he does forget himself and become a trifle uppity his wife and daughters will soon put him in his place. Besides, my agent, Mercer Hughes, will be joining us. You’ve met him, haven’t you?’

‘No,’ Susan said, ‘actually, I haven’t.’

‘Then, my dear’ – Miss Proudfoot patted her knee – ‘you’ve a treat in store. There’s no one – repeat no one – quite like Mercer Hughes.’

By the time Matt Hooper reached Stratton’s Dining Rooms, Georgie was already taking in the menu board. It was about the only thing Georgie was allowed to do unsupervised, for the poor lad was several pence short of a shilling and too clumsy to be trusted with saucepans, dishes or knives.

‘Here, Georgie, let me give you a ’and with that,’ Matt Hooper offered.

Taking an end of the board, he backed through the street door into the empty shop. The tables had been cleared but the green and white chequered cloths that Nora’s auntie had sent over from Limerick had not been removed. Dishes clattered in the back kitchen where sinks, stoves and storerooms were situated and which served Nora Romano and her family as a living room when the business of the day was over. Matt leaned the blackboard against the base of the window so it wouldn’t drip on the linoleum.

‘Switch the slat, Georgie,’ he said. ‘I reckon you’re closed for the night.’

Georgie Romano was over six feet tall, a head taller than Matt. He still had the baffled stare of an eight-year-old, though, and only his size and the stubble that fringed his jaw indicated that he wasn’t some freakish child but a man in his twenties.

‘Mammy, Mammy says …’

‘Mammy says you’re closed, Georgie.’

‘She – she told you ’at?’

‘She did.’

The obvious question was ‘when’ but nothing was ever obvious to Georgie. He clapped his hands and tackled the wooden slat that hung from a cord on the window. He took it in both fists as if he were about to crush it like a tin can and, tongue between teeth, twisted it from ‘Open’ to ‘Closed’.

‘Okay, Mr ’Ooper?’ he asked anxiously.

‘Spot-on, Georgie. Spot-on,’ Matt said and, with a hand on the young man’s shoulder, steered him through the shop into the kitchen.

Nora Romano’s heart skipped a beat when she heard Matt barging about. She had her kids, her lodger and her cooking but Matt Hooper was the nearest thing she’d had to a man of her own since her husband, Leo, had emptied the cash drawer and scarpered with the tarty little piece from the Fawley Street fish bar.

Leo had always been an idle beggar whose ‘line of work’, as he called it, involved hanging about racetracks and drinking clubs and running errands for any of the shifty mob, Jews, Irish or Italians, who’d stand him a gin and grape juice and drop him a few bob now and then. When she’d first met him she’d asked him what kind of a name Leo was, fearing it might be Jewish, and he’d told her he’d been called Leonardo after the painter to distinguish him from a million other blokes named Romano who’d been born in the Eternal City.

The only decent thing Leo had ever done was help secure the lease of the dining rooms from old Harry Stratton. Even so, she’d been shaken by the manner of his departure. She’d even considered packing up and taking Georgie and her daughter, Breda, off to Limerick. Might have done it too if Matt Hooper hadn’t told her how much he’d miss her steak and onions.

‘Susie get away all right?’

‘Right as rain,’ Matt answered.

‘Turn on the waterworks, did she?’

‘Not ’er.’

‘You?’

‘Nah, not me neither,’ Matt said. ‘It ain’t like she’s goin’ off for good.’

He sat down, wiped his face with his cap, hung the cap on the knob of the chair then disconsolately rested his chin on his palm. He had broad shoulders, a determined sort of chin, hair greying above the ears and blue-grey eyes that didn’t seem to have a laugh in them. He was handsome, though. Even Breda thought so and Breda, at nineteen, was notoriously picky.

‘Anything good in the pot, Nora?’

‘Mince,’ Georgie chipped in. ‘Mince on Friday, Mr ’Ooper.’

‘Got enough for one more?’

‘I reckon we can find you a plate,’ said Nora.

Minced beef on toast was not the best meal on her menu but she did her market shopping on Saturday and on Friday night the family had to make do with leftovers. She placed four thick slices of bread under the grill of the big gas stove then stepped into the corridor at the rear of the kitchen and called to Breda, who was putting on her face in the bedroom upstairs.

‘Can’t believe Susie’s gone,’ Matt said. ‘It’s not for me to stand in ’er way, though.’

‘Stand in her way?’ said Nora. ‘What you talkin’ about? It was you what pushed her in the first place.’

‘I only put a word in.’

‘Some word!’ said Nora. ‘From what I hear you practically had an arm lock on that Proudfoot woman.’

‘It was all done through the typing agency.’

‘It ain’t being done through no typing agency now, though, is it?’

‘That’s true,’ Matt Hooper admitted. ‘But if things don’t work out with Miss Proudfoot, the agency’ll take Susie back. She’s the best they got.’

‘Not that you’re biased, like.’

He had the decency to grin. ‘Nah, not that I’m biased.’

Matt’s wife, Freda, had died soon after giving birth to Susan and his mother had stubbornly refused to raise another baby. His father had slipped him a few bob to pay for a wet nurse and had offered sound advice. ‘First thing you do is find some old woman to tend the kids while you’re on shift. Second thing you do is register as a pacifist. Keep you out o’ the war an’, most like, on the dock. Be a long war, no matter what Asquith tells us. War or no war, the merchants of London won’t starve. So tighten your belt, son, an’ go an’ do what has to be done for your kiddies.’

Matt had followed his father’s advice to the letter. He’d sworn off tobacco, booze and women, every pleasure except an occasional night at the Adelphi when Leo Romano had finagled free tickets from one of his dubious acquaintances. But now, as he watched Breda Romano push away her empty plate and fish for the packet of ciggies she kept tucked in the leg of her drawers, a trace of the old appetites rose up in him again.

Breda tapped the pack, flipped out a cigarette, lit it, inhaled deeply and blew smoke though her nose. ‘Whatcha gonna do now, Mr ’Ooper,’ she said, ‘now you got nobody to go ’ome to?’

‘But I do have somebody to go ’ome to,’ Matt answered.

‘Who’s ’at then?’

‘Ronnie.’

‘Ronnie!’ The girl snorted. ‘You ain’t gonna see none o’ Ronnie tonight.’

‘Why’s that?’

‘He’ll have himself a fancy piece. Ain’t you got a fancy piece, Mr ’Ooper?’

‘Nah,’ Matt said. ‘I ain’t got a fancy piece.’

Breda wetted her lips and sat back. She had a chest on her, that much he had noticed, and she knew how to use those big Italian eyes. If he didn’t know better he’d swear she was flirting with him.

‘’Ow about my ma,’ Breda said. ‘Ain’t she fancy enough for yer?’

‘Breda!’ Nora snapped.

‘I’m just ’aving ’im on,’ Breda purred. ‘Well, Mr ’Ooper, what is it? Ain’t my ma fancy enough for you? Or ain’t you man enough for ’er?’

Matt said, ‘You want me to answer your question, Breda, it’ll cost yer.’

‘Cost me what?’

‘One of them cigarettes.’

The girl smirked. ‘Yeah, right!’

‘Nah,’ Matt said. ‘I mean it.’

She shrugged, tapped the last cigarette from the packet, lit it and held it out across the table. When Matt reached for it she drew it away. He reached again and again she withdrew it, then, like the strike of a snake, he shot out a hand and caught her wrist. He drew her forward until her breasts were crushed against the table top.

Breda, round-eyed, opened her fingers and let him remove the cigarette.

Matt Hooper sat back and, tipping his chin towards the ceiling, savoured the cheap little smoke as if it were a fine cigar.

‘Now,’ he said thickly, ‘what was your question again?’

There was something quaint about Hereford railway station, something not quite twentieth century. Lugging her suitcase, Susan followed her employer out on to the pavement to be greeted by a great canopy of sky, a broad well-lit high street and a taste of country air which, if not exactly wine, was a deal fresher than the stuff that seeped through the back streets of Shadwell. A mud-spattered, open-topped motorcar was parked outside the station. A man in a frayed army trench-coat, corduroy breeches and rubberised boots stood by it, grinning.

Dropping her briefcase, Vivian wrapped her arms around him.

‘David, you scoundrel!’ she cried. ‘My God, you look like a scarecrow.’

‘Been busy, old sausage. How you?’

‘Me fine. Starved.’

‘Gwen’s waiting supper.’

‘Glad to hear it.’

‘Who’s this?’

‘My new assistant, Miss Hooper.’

He offered his hand. ‘Proudfoot.’

The hand was dry and hard, the grip not quite crippling.

‘Pleased ter – to meet you, sir,’ said Susan politely.

Mr Proudfoot heaved Vivian’s rucksack into the rear seat, followed it with Susan’s suitcase, then, taking Susan’s arm, helped her into the car. He slid into the driver’s seat next to his sister.

‘Now, remember, David, this is not Kop Hill,’ Vivian told him, ‘and you are not Raymond Mays. Don’t go showing off.’

‘Yes, my dear,’ David Proudfoot said, slammed the car into gear and shot it forward into the high street while Susan cowered nervously among the luggage and, quite literally, held on to her hat.

In London you didn’t have to think about where you were going. East was east and west meant the West End and if you got lost somewhere in between there was always a bus route to follow, a handy Underground station or some passer-by willing to steer you in the right direction. There were no such navigational aids in the country, Susan realised. Once they’d left the town behind, churches, humped stone bridges and timbered buildings leapt at her out of the darkness with, here and there, the glimpse of a barn or whitewashed cottage.

When Mr Proudfoot swung the car into a rutted lane the suitcase toppled into her lap, the rucksack pressed her against the door and it crossed her mind that if the door flew open she would be thrown out and no one – certainly not Mr Proudfoot – would be any the wiser.

The car flew past a listing signpost – Hackles – and a few yards further on a lawn, silvered by moonlight, the posts of a tennis court and – Susan blinked – a man seated on top of an umpire’s chair. He rose, swaying. ‘At last the goddess has come upon us,’ he shouted at the pitch of his voice. ‘About bloody time too.’

‘Is that him?’ Susan asked. ‘Is that your agent?’

‘Yes,’ Vivian answered. ‘That’s Mercer playing the fool, as usual.’

The car nosed to a halt in front of a huge, two-storey, Tudor-style farmhouse and Susan sat back and let out her breath. Wherever she was and however she’d got here, she knew that at last she’d arrived.

He loped across the lawn, stepped over the knee-high hedge that bordered the tennis court and, in a gesture that struck Susan as very French, kissed Vivian first on one cheek and then the other. He glanced at Susan and obviously deciding that she wasn’t worthy of attention, put an arm about Vivian’s waist and escorted her along the pathway to the porch.

Four gnarled pillars supported a steep thatched roof that reminded Susan of a Rackham illustration in a book of fairy tales that she’d admired in the bookcase in Sir Alfred Pennington’s chambers. Sir Alfred had noted her interest and, being a kindly old gent, had taken out the book and had shown it to her. He had turned the pages one by one, very gingerly, his hands so pale and spotted that they might have been drawn by the fairy-tale artist too.

‘Theory is’ – David Proudfoot came up behind her – ‘that the whole tottering edifice started with the porch and just growed like little Topsy.’ He paused. ‘I don’t suppose you know who little Topsy is, do you?’

Susan knew perfectly well who little Topsy was – she’d read Uncle Tom’s Cabin in three different versions, courtesy of Shadwell public library – but she nursed a suspicion that ignorance was expected of her.

She shook her head. ‘No, sir. I don’t.’

‘My daughter, Caro, was afraid of that porch when she was little,’ Mr Proudfoot said. ‘Wouldn’t set foot inside it even in broad daylight. Supposed to be haunted. Not the porch, the house. Ghost of some Civil War heroine is reputed to float about upstairs but I’ve never seen her. Not scared of ghosts, are you?’

‘Never met one, sir,’ said Susan. ‘Don’t suppose they’ll do me no harm.’

‘Sensible attitude,’ David Proudfoot said. ‘Viv will give you the grand tour tomorrow, I expect. The house is not entirely without historical merit. Hungry?’

‘Yes, sir, I am rather.’

‘Straight ahead,’ David Proudfoot told her. ‘Watch out for the step.’

He ushered her under the brow of thatch, through a doorway into a hall.

Black-painted beams and a sagging plaster ceiling loomed overhead. An electrical light bulb dangled from a twisted cord and a big lamp in a parchment shade flickered on a corner table. There were doors everywhere, black-painted like the beams. David Proudfoot nudged her with the suitcase.

‘Kitchen’s at the end of the passage,’ he said. ‘I’ll take the luggage upstairs. Do you need to make use of the facilities?’

‘The what?’ Susan said.

‘The lavatory.’

‘No,’ she said. ‘Thank you all the same.’

She took off her hat, tidied her hair, then, throwing back her shoulders, pushed open the door and headed along a passageway. A moment later she found herself in a kitchen so vast that it might comfortably have accommodated three families from Shadwell with room to spare for lodgers and dogs.

‘Ah, there you are!’ said Vivian. ‘Where’s David?’

‘Taking the luggage upstairs,’ said Susan.

‘Is he, indeed?’ said Mercer Hughes. ‘Isn’t that your job?’

‘Now, now, Mercer,’ said Vivian. ‘She isn’t a skivvy, you know.’

A slim, very pretty woman with short fluffy fair hair was folding napkins. Beside her, holding a casserole dish wrapped in a towel, was a plump older woman. Two girls, clearly sisters, were seated at a long oak table set for supper. Mercer Hughes stood behind the elder of the girls, a stocky blonde not quite Susan’s age.

‘Where do you find them, Vivian?’ he said. ‘Selfridges’ budget basement? Where are you from, my dear? You’re a little too well scrubbed for Silvertown. Stepney, by any chance?’

Susan had encountered too many arrogant bullies while temping in the City to be cowed by a literary agent.

‘Shadwell,’ she said. ‘You’re out by only a few streets, sir. You seem to know the East End of London pretty well. Were you born there?’

Mercer Hughes laughed. ‘I suppose I asked for that. Must say, Miss …’

‘Hooper,’ Vivian informed him. ‘Susan Hooper.’

‘Must say, Miss Hooper, you don’t sound like a citizen of Shadwell.’

‘Chelsea,’ piped up the younger girl. ‘She sounds like Chelsea.’

‘She doesn’t sound a bit like Chelsea,’ said the blonde waspishly.

‘Girls,’ the woman spoke up, ‘may I remind you it’s not polite to discuss someone in the third person.’ She glided round the table and held out her hand. ‘I’m Gwen Proudfoot. These uncultured creatures are my daughters, Eleanor and Caroline. Mrs Wentworth is our cook. You, I imagine, are Vivian’s new secretary.’

‘Oh, a typist!’ Caro Proudfoot said. ‘How exciting! Perhaps you’ll teach me to type, Miss Hooper. I’d so much like to learn.’

‘Susan won’t have time to teach you anything,’ Vivian informed her niece. ‘She’ll be far too busy. We’re here to work.’

‘Hammering out your next bestseller?’ Eleanor asked.

‘Absolutely,’ Vivian answered.

‘Another Bible story?’ said Caro.

‘In Defence of Herod was hardly a Bible story.’ Mercer Hughes tapped the little girl lightly on the crown of her head. ‘Haven’t you read it?’

‘Papa wouldn’t let me,’ Caro pouted.

‘Papa wouldn’t let you what?’ David Proudfoot entered the kitchen. ‘What slander is this you’ve cooked up against me now?’

‘Aunt Vivian’s book,’ said Eleanor.

‘Oh, that!’ David said. ‘No, well, you’re far too young for political manifestos, Caroline.’

‘I’m twelve,’ Caro reminded him. ‘You let Eleanor read it.’

‘And how did Eleanor find it?’ Vivian asked.

‘Incredibly dull,’ Eleanor answered.

‘Oh, you fibber, Elly. You said you loved it,’ Caro protested.

‘To protect my tender feelings, no doubt,’ said Vivian.

‘Absolutely!’ Eleanor Proudfoot declared and at that moment, Susan thought, not only looked but even sounded like a miniature version of her aunt.

Georgie had fallen asleep slumped across the table, his head cradled on his arms. Nora had stacked cups and plates on the draining board and had placed the greasy pots and pans in a neat row on newspapers on the floor.

All very orderly and methodical, Matt thought, her routine. It didn’t occur to him to pick up a dish mop and help out. Eccentric he might be but not as eccentric as all that. Half the women in Pitt Street already thought he was a sissy because he wouldn’t let his precious Susan play in the street and, like some fussy old hen, called her in to do her homework or eat her bite of supper off a plate. He’d even been spotted in the public washhouse rinsing blouses, knickers and vests, and whistling as if he were enjoying himself.

Nora was still trim and moved without the shuffle most women of her age developed when their arches fell. She was no doll like Breda, had never been a doll like Breda, not even when Leo had picked her out of the crowd. For a woma. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...