- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

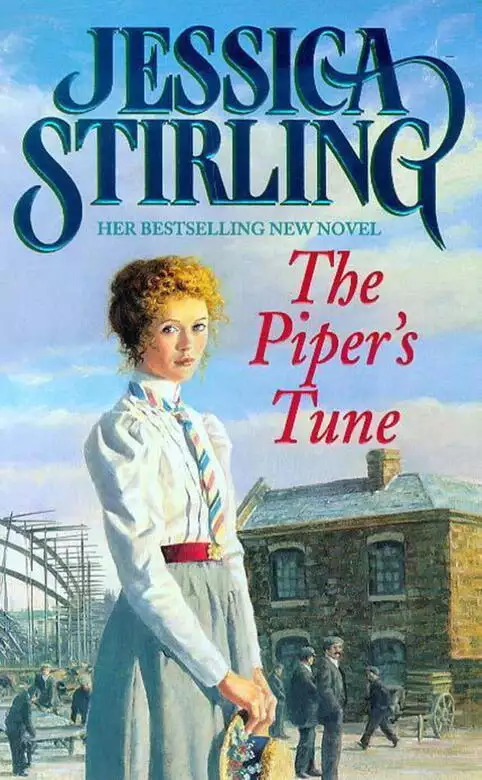

Jessica Stirling's Glasgow comes to scintillating life in the story of love and fortune set in Edwardian Scotland, the first in a trilogy. Lindsay Franklin's life is an adventure she has just begin to enjoy. At eighteen, Arthur Franklin's cosseted daughter has left her Glasgow school and finds her role as a marriageable young lady with a widowed father more than agreeable. But Lindsay's life takes an unexpected turn when her ambitious, charming Irish cousin Forbes comes to Glasgow to join the family business. When her grandfather retires Lindsay is unexpectedly left with a share in the business - and equally unexpectedly, she decides that she must master that business as carefully as her male cousins. What is not surprising is that several eligible men decide that it is time to master Lindsay... As the mysteries of shipbuilding open to her, and the puzzle of male behaviour becomes both more fascinating and more dangerous, Lindsay will have to make some fateful decisions. Decisions that will make or mar her whole future.

Release date: January 19, 2012

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 493

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Piper's Tune

Jessica Stirling

Floating Capital

‘What,’ Lindsay said, ‘do you want to do this afternoon? Go out for a walk?’

‘In this dreary weather?’ Forbes said. ‘No, I’m perfectly happy to sit tight and wait for Runciman to fetch us afternoon tea.’

‘Miss Runciman.’

‘Miss Runciman then.’

Forbes stretched an arm along the back of the sofa and toyed with a lock of Lindsay’s hair. She felt no particular excitement. She knew by experience that nothing would come of his flirting. She would have preferred to be out of doors, even if only for a short promenade along Brunswick Crescent. Forbes was right, though; the weather was not conducive to exercise.

A mild, misty drizzle enveloped Clydeside. Drab evergreens and trees not yet in bud dripped moisture, the big windows of the drawing-room were opaque with condensation. Church that morning had smelled distinctly damp, not wintry but bluff and loamy. The weather had failed to quash Papa’s enthusiasm for the massed choir rehearsal, however. He had hurried off straight from kirk to catch a bite of lunch at Harper’s Hill before Donald and he walked the short distance to St Andrew’s Halls together.

Forbes had appeared at the front door about half past two o’clock. Miss Runciman had shown him into the drawing-room.

Lindsay had been been upstairs in the library engrossed in the latest issue of The Shipbuilder when Miss Runciman, wearing her everlasting smile, had announced Forbes’s arrival. Showing no sign of annoyance at the interruption, Lindsay went downstairs at once, prepared to behave as if she were overjoyed. The sight of Forbes in his Sunday best had given her a lift, for however tedious she found his conversations of late his charm more than made up for it.

By half past three, though, she was bored again. She was loath to admit even to herself that she took less and less pleasure in Forbes’s company these days. She still loved him, of course she did, but she could hardly recall the magnetism that had once attracted her to him.

He toyed with her hair, then, letting his hand slide from her shoulder, appeared to lose interest. He rolled out of the sofa, put his hands in his trouser pockets and meandered to the window.

Then he said, ‘Are you in a position to get married yet?’

He jingled coins in his pockets and did not seem in the least interested in her reply.

‘What do you mean, Forbes, “in a position”? Of course I’m in a position to get married. I’m single and over twenty-one.’

‘I mean,’ he said, ‘financially.’

‘Ah!’

He returned to the sofa and leaned his forearms on the back of it, giving her his full attention. ‘How much did your trust turn up?’

‘I’m not sure you have a right to ask me that,’ Lindsday said.

‘Oh, come on, my love,’ Forbes said. ‘If I’m going to take you on then I’m entitled to know how much you’re worth.’

‘What did you say?’

‘Sorry.’ He smiled sheepishly. ‘That didn’t sound right, did it?’

‘Just for a moment you sounded like a real Irish horse-coper.’ Lindsay let her pique show. ‘Take me on indeed! What a callous way of putting it.’

He slid an arm about her, cupped her shoulder, nuzzled her neck. His cheek was shaven smooth and she could smell cologne. She wondered when he had taken to wearing cologne.

‘I mean,’ Forbes said, ‘if we plan to set a date this year then we have to be practical about it. I want you, Linnet. Can’t you tell how much I need you? I really can’t wait much longer.’ He kissed her neck, letting his lips linger. ‘That’s all I meant.’

She felt guilty. The touch of his lips was so tender and loving that she could not help but forgive him. She covered his hand with hers. It was so still and clammy in the drawing-room that the rustle of her skirts sounded like a crackle of thunder. Where was Miss Runciman? Probably in the kitchen personally preparing the neat little sardine sandwiches that Forbes professed to adore. What would Miss Runciman say, Lindsay wondered, if she came into the drawing-room and found them sprawled on the carpet in a passionate embrace?

‘It’s too early to consider announcing our engagement,’ Lindsay said. ‘I’m no less keen than you to be married but my father does have a point.’

‘What point is that, sweetheart?’

‘You’re not twenty-one yet.’

‘What’s that got to do with it?’

‘You’re not – not established.’

He came swiftly around the sofa, seated himself by her side and took her face between his hands. ‘Look at me, Linnet. Do I seem like a boy to you?’

She shook her head. His hands tightened, fingertips finding and resting on the pulses behind her ears. He said, ‘Do you think a man has to be twenty-one to make a woman happy?’

‘Forbes . . .’

‘Linnet, I don’t want to lose you.’

‘Lose me?’

‘To someone else.’

‘There is no one else.’

He took a deep breath, released it. ‘No,’ he said. ‘No, of course there isn’t.’ He slid his hands from her face and sat back. ‘Anyhow, I thought we were going to be practical.’

‘And talk about money, you mean?’

‘If you like,’ Forbes said.

‘Are you asking me how much I’m worth?’

‘Oh, I see. That’s what’s got you riled, is it? No, Lindsay, that’s not what I’m asking, not at all.’

‘What then?’

‘I want to know how much we’ll be worth when the time comes.’

‘Haven’t you asked Martin?’

‘He claims he doesn’t know.’

‘Donald then, or Pappy?’ Lindsay said. ‘You’re fully entitled to see the figures – or your mother is. I’m not sure how trust law works when juveniles are involved.’

‘Juveniles! Jesus, I hate that expression. I’ll be twenty-one next year. I’ll have finished my diploma course and most of my managerial training. I’ll be established. You’ve seen the figures. You know what I’ll be earning. Will it be enough, Linnet, just tell me that? Can we make do?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Forbes. Of course we can make do. Good Lord, you’re carrying on as if we were being condemned to nail-biting poverty.’

‘I don’t want to have to depend on anyone.’

‘I applaud that sentiment,’ Lindsay said. ‘But it doesn’t alter the fact that my father doesn’t want us to marry until you’re older.’

‘How old? Twenty-five, thirty-five? Forty, fifty? Until my cock withers and drops off?’

‘Forbes!’

‘Well, it’s the truth, Linnet. Your daddy doesn’t want you to get married at all, especially not to me. He likes having his little girl at home. It makes him feel ageless. And then along comes this hairy Dubliner—’

‘Nonsense! Absolute nonsense!’

‘Are you blushing?’

‘No.’

‘You are, damn it, you’re blushing.’ He touched her again, brushing her hair with his palm. This time she shivered. ‘Is it that naughty word I used? I notice you know what it means?’

‘Forbes, please. Don’t.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘You’re right as usual. I mustn’t taunt myself. We’ve got to be sensible, practical – nice. Nothing else for it.’

‘Twelve hundred pounds,’ Lindsay said.

He whistled.

‘Twelve hundred and eighteen pounds and eleven shillings.’

He whistled again.

‘Including accrued interest.’

‘At what rate?’ Forbes asked.

‘I’ve no idea,’ Lindsay answered.

‘Say, eleven hundred base over three years. Say, three hundred and sixty per annum. Halve it for one per cent. Multiply by seven. Good God!’

‘It’s a great deal of money.’

‘I’ll say it is.’ He whistled once more, not silently. ‘If you add in the interest, I’ll be picking up not far short of five thousand quid on my birthday.’

‘Had you no idea that Franklin’s were doing so well?’

‘None. Not really. Not in hard cash.’ He permitted himself a grin. ‘Small wonder that Rora Swann considers our Martin a rare old catch.’

‘I don’t think the money matters. I think she loves him.’

‘Of course she does,’ Forbes said. ‘Same as I love you.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Well, I can’t just be after your money, my love, can I?’ He eased himself back in the sofa and put his hands behind his head. ‘Do you know what the arithmetic means, Lindsay?’ He did not allow her to answer. ‘It means we don’t have to kowtow to anyone. We can do as we damned well please, whenever we please.’

‘Forbes, I really don’t think we should get carried—’

With startling agility he leaped forward and snared her about the waist. He was alert and animated, no longer distant. No longer boring. He kissed her mouth firmly, kissed it again.

‘Let’s do it, Linnet,’ he said.

‘Do – do what?’

‘Between you and me, Lindsay, just between ourselves, let’s agree a date.’

‘For what?’

‘Our wedding, of course,’ said Forbes.

Tom could not make up his mind if the Hartnells deliberately set out to make him feel small or if it was merely negligence that caused them to offer him a low wooden chair. He didn’t think that Florence was the devious type but he was less sure about her husband. Something about Albert rubbed Tom up the wrong way and it would not have surprised him to learn that the chap had sawn the legs off the chair just to increase his awkwardness.

The tenement apartment was furnished with odd bits and pieces of furniture and not much of it at that. It was, however, clean; far too clean, not just spotless but scrubbed within an inch of its life, every plate, spoon and fork, every square inch of worn linoleum buffed by one of the damp bristle brushes that were propped like artillery shells on the draining board over the sink. Even the pan of tripe and onions that bubbled on the stove smelled more antiseptic than appetising.

Tom tucked his heels under the spar of the chair and, bent almost double, tried not to click his chin on his knees. Florence and Albert were seated at the kitchen table. There was nothing on the table, not so much as a crumb.

‘You’ve brought payment, I assume?’ said Florence.

‘I have,’ Tom answered.

He fumbled to free an elbow, dipped into his overcoat pocket and produced a signed cheque. He craned forward, chest to thighs, reached up and offered the cheque to the couple. Albert glanced at Florence. Florence nodded. Albert took the cheque and passed it to Florence. Florence studied it with care.

‘I think you’ll find it in order,’ Tom said.

‘Hmm, you took your time with it,’ Florence said.

‘I’ve been away on business. Working.’

Tom gave the word ‘working’ a little extra emphasis. He had a suspicion that work was anathema to Albert Hartnell who, when interrogated, admitted only to being a ‘contractual storeman’, whatever that entailed, and would not be drawn into naming his current employers. If, fourteen years ago, Tom had known the Hartnells better he would not have handed his daughter into their care: it was too late to reclaim Sylvie now, though.

Albert said, ‘Africa again?’

‘Portsmouth.’

‘At the naval dockyard?’ Albert said.

‘Yes,’ Tom said, to save further explanation.

‘Rule Britannia!’ Albert said. ‘Britain rules the waves, what!’

‘Albert,’ Florence warned in a dreadfully deep voice. ‘Enough out of you.’

Tom squirmed. His joints were locking up. He eased back, tried to stretch, felt the knob of the chair-back dig into the base of his spine like a poking finger.

‘Where’s Sylvie?’ he said.

‘Out,’ said Albert.

‘Resting,’ said Florence.

Tripped on a small lie, the Hartnells frowned at each other.

‘Which is it to be?’ Tom said. ‘Out or resting?’

‘Ah, is she in then, dear?’ Albert said, widening his eyes. ‘Has she returned from being, from being – out?’

‘She’s lying down in the room,’ said Florence.

‘Of course, of course she is,’ Albert said. ‘Having a nice wee nap, I expect. I wouldn’t want to disturb her, would you, Tom?’

‘What’s wrong with her?’ Tom asked. His indifference to Sylvie’s welfare was only skin deep, it seemed. He could not entirely erase the guilt and responsibility that were the very essences of fatherhood. ‘Is she ill?’

‘Ill? Oh, no – hah-hah – course she ain’t ill,’ said Albert.

‘She’s – unwell, shall we say,’ Florence told him.

‘I’d like to see her,’ said Tom.

‘She is asleep,’ said Florence.

‘Has she been missing her schooling?’

‘Not a single day,’ said Florence. ‘She isn’t that unwell.’

‘I see,’ said Tom uncomfortably. ‘I trust she hasn’t been overdoing it.’

‘What do you mean?’ said Albert. ‘Overdoing what?’

‘Church work, Mission work, school,’ Tom said. ‘Burning the candle, sort of thing.’ He was tempted to add ‘like her mother before her’, but he did not consider the remark appropriate. Besides, Florence had been just as shocked as he had been when her sister’s moral collapse came to light.

‘She’s very dedicated to the Coral Strand,’ said Florence.

‘No stopping her,’ said Albert.

‘I would like to see her,’ said Tom again.

‘She’s asleep. I’m certain she’s asleep.’

‘I won’t waken her,’ Tom promised.

‘You might,’ said Albert.

Tom tried to rise with dignity but the little chair seemed to be glued to his bottom and rose with him, sticking out like some piece of medieval mummery. He struck at it with his elbow, failed to dislodge it and, fearing for his balance, sat down again.

‘I’ll wait,’ he said.

‘Wait?’

‘Until she wakens. Or until you waken her for supper.’

‘Not enough in the pot for four,’ said Florence.

‘I’m not scrounging,’ said Tom. ‘I just want to see that Sylvie’s all right.’

‘Why shouldn’t she be – all right?’ Albert enquired.

‘I don’t know,’ Tom said. ‘I haven’t seen her in months, you know.’

‘She hasn’t changed,’ Florence said.

‘We thought you’d forgotten about her,’ said Albert.

‘Is that what Sylvie thinks too?’ said Tom.

‘Oh, no,’ said Florence calmly. ‘She’s a real pet lamb, our Sylvie. She goes her own way and gets on with her own life.’

‘In the service of others,’ said Albert.

‘Yes,’ Florence said. ‘In the service of others.’

‘She finishes her schooling soon, doesn’t she?’ Tom said.

‘In July, yes,’ said Florence.

‘What will she do then? College, perhaps?’

‘She’s a girl,’ said Albert.

‘Some girls do go to college these days,’ said Tom. ‘If it’s a matter of cash, I don’t mind paying for her to learn how to utilise a typewriting machine, or some other skill for that matter.’

‘Park School girls do not become stenographers,’ said Florence.

‘Don’t they?’ said Tom.

‘In any case,’ said Albert, ‘she wants to be a missionary.’

‘A medical missionary?’ said Tom, surprised.

‘She ain’t clever enough for medicine, alas,’ said Albert. ‘Knows her own limitations, does our wee sweetheart. No, she has her heart set on working on the home front for the Coral Strand. She’ll do the training course, like I did.’

‘You didn’t,’ Florence reminded him. ‘I did.’

‘Same thing, dearest,’ said Albert. ‘However, working for the Coral Strand is what our Sylvie has set her heart on.’

‘You won’t stand in her way, will you, Tom?’ said Florence.

‘No, probably not,’ Tom said. ‘I’d like to find out more about it, though.’

‘More about what?’ said Albert.

‘This organisation: the Coral Strand. What precisely is it? What does it do with its funds? Where are its offices and what training will Sylvie receive?’

Florence glanced at her husband who raised a weak eyebrow.

Florence said, ‘We can answer all your questions, Tom.’

‘Quite right and proper, quite natural for you to ask,’ said Albert magnanimously. ‘Got the papers handy, dearest?’

‘Not just to hand.’ Florence paused. ‘Next time you come, Tom, I’ll have them all laid out for your inspection. Meanwhile, to save you hanging on, I’ll slip through to the room and see if she’s awake yet.’ Florence smiled. ‘If she’s not you can have a little peep at her, Tom. Would that not be nice?’

‘Yes,’ Tom said. ‘That would be very nice. Thank you.’

‘No thanks necessary,’ Albert said, and like a true gentleman rose to open the door for his wife.

She lay with her head on a silk pillow, one small fist curled against her cheek. Her hair was spread about her head and babyish perspiration dewed her upper lip. She wore nothing but a shift. Tom could see the outline of her breasts against the cambric, the nipples curiously elongated. She looked, he thought, slightly flushed but not unhealthy. He was embarrassed to be hovering over her while she slept, unaware that she was being observed, but the fact was that he preferred her asleep to wide awake.

The net curtain over the window was too flimsy to filter out the evening light and he could make out Sylvie’s clothes folded over a high chair, drawers, stockings, an embroidered garter of which the staff of the Park School would certainly not approve. On the mantel above the fireplace two plaster-cast bookends held a dozen books in line; two little black boys knelt in prayer, foreheads pressed to Latin primers and English grammars as if to acquire knowledge by osmosis. There were no other ornaments in the narrow bedroom, not even functional objects like a mirror or a candlestick and the only furnishings were a dressing-table and a head-high tallboy.

Sylvie sighed, opening one hand and closing it again.

‘Aw, she’s dreaming,’ Albert whispered. ‘Sweet dreams, dearest.’

‘Have you seen enough, Tom?’ Florence murmured from the doorway. ‘It’s just flushing, quite natural in a girl of her age.’

‘Yes.’ Tom eased himself out of the alcove. He had seen enough, more than enough. It was the first time that he had observed his daughter’s slumbers since her infancy, and somehow he wished he hadn’t.

‘I’ll tell her you called, shall I?’ said Florence.

‘Please do,’ said Tom, and left.

Arthur Franklin had nothing against marriage between cousins. The upper brackets of the shipping industry were full of such unions, encouraged to protect the closed nature of family firms and keep predators firmly beyond the pale. Arthur was willing to concede that Forbes McCulloch would probably wind up as his son-in-law but until that day came he was determined that Forbes would not be given the run of the house.

He entered the hall cautiously, handed hat and overcoat to Eleanor Runciman and peeked at the door that led to the drawing-room.

‘Is he still here?’

‘No, sir. He’s gone.’

‘He was here, though?’

‘Yes, most of the afternoon and much of the evening.’

‘I guessed as much,’ Arthur said. ‘When neither Lindsay nor he showed up at Harper’s Hill for dinner I thought they’d be here.’

‘I provided him with dinner.’

‘Did you indeed?’

‘I assumed that you had gone back with your brother,’ Eleanor said, ‘and that there would be meat to spare here.’

Arthur hesitated, then, still buoyant with the pleasures of the afternoon, headed for the parlour.

‘Eleanor, gin or brandy?’

‘Brandy, if you please.’

A late evening tête-à-tête had become part of the pattern in Brunswick Crescent. Arthur liked to have someone to talk to at the end of the day. Now that Lindsay was growing away from him he depended increasingly upon the housekeeper to provide him with company and, when required, advice. He did not, of course, take advantage of their intimacy and Eleanor was far too respectful to impose upon their close relationship.

‘Did you dine with them?’ Arthur said.

‘Of course.’

‘Any plans discussed?’

‘What sort of plans?’

‘Matrimonial plans.’

‘Not in front of me,’ Eleanor said.

‘Pappy declares they’ll marry before the year’s out.’

‘Do you have no say in the matter?’

‘It seems not,’ Arthur said. ‘It seems I’m just expected to conform.’

‘You could surprise them.’

‘Could I? How?’

‘Give them your blessing.’

Arthur was seated in an armchair, she on the sofa.

He said, ‘You rather like the Irish cousin, don’t you?’

‘I see no harm in him.’

Arthur smiled. ‘Because he’s a handsome young devil, eh? Does he remind you of that chap from Cork?’

‘Chap from . . . Oh!’ Eleanor almost blushed. ‘How did you hear about the chap from Cork?’

‘You’ve told the tale to Lindsay so often it would be a miracle if I hadn’t heard it. I’m not deaf, you know,’ Arthur said. ‘Fiancé, was he?’

‘No, not – not quite, sir.’

‘Not good enough for you, eh?’

‘Rather the other way around, I fear.’

‘How long ago was this near-run thing?’

‘Years and years ago. Too many to count.’

‘Why do women have such a soft spot for Irishmen?’ Arthur sat back and unloosed his collar and cuff links. Eleanor held his whisky glass while he did so. ‘I mean, is it the gift of the gab or the brooding looks or the elfin charm? Damned if I can see the attraction.’

‘I think’ – Eleanor gave him back the glass, fitting it carefully into his outstretched hand – ‘I honestly think it’s the charm.’

‘Skin deep.’

‘That’s as may be,’ Eleanor said. ‘Better skin deep than not at all.’

‘Don’t the Scots have charm?’

‘Some do, some don’t.’

‘Aren’t I charming enough?’

‘At times, sir, yes – fairly.’

Arthur shook his head ruefully. ‘Damned with faint praise.’

‘It isn’t charm that makes a marriage.’

‘Really? What is it then?’

‘Mutual respect.’

‘Try telling that to two young people who fancy themselves in love.’

‘I would not dare,’ said Eleanor.

She had gauged his mood at last. He wasn’t really fretting about Forbes McCulloch. The great lift of voices that had filled St Andrew’s Halls that afternoon had lifted his spirits. For a time, she thought, he had soared above pettiness while Donald and he, and two or three hundred other singing souls, had shared in musical communion. She wished sometimes that she had a voice that could soar and that she might share that exquisite pleasure with him.

She said, ‘Is there no one for you, sir?’

‘No one? What do you mean, Eleanor?’

‘I mean . . .’

Arthur laughed, a little uncomfortably. ‘Ah, so you’re still dwelling on the fellow from Cork, are you? Lost opportunities, and all that?’

‘I was thinking of your welfare, your happiness.’

‘I’m happy enough with things as they stand.’

‘And after Lindsay goes?’

‘She won’t be far away. McCulloch has his work . . .’

‘She need not go at all,’ said Eleanor.

‘Hmmm?’

‘They could live here with us. With you, I mean.’

‘So,’ Arthur said, still not riled. ‘So that’s what’s on my darling daughter’s mind, is it? Did she ask you to sound me out?’

‘I think it’s only a vague suggestion.’

‘Lindsay’s idea, or McCulloch’s?’

‘It is a very large house for a single gentleman to occupy,’ Eleanor said.

‘I might consider moving.’

‘Do you wish to move?’

‘No,’ Arthur said. ‘But I think I’d prefer moving to sharing.’

‘It would be a simple thing to arrange,’ Eleanor said. ‘The couple could have the entire upper floor and use the drawing-room for their parlour.’

‘Where would you go?’

‘I could take the little bedroom on the second floor, next to Nanny.’

‘Cramped, very cramped,’ said Arthur.

Eleanor paused. ‘Nanny may not be with us for much longer.’

Arthur sighed. ‘That’s true.’

‘It is, of course, only a vague suggestion.’

She watched him swirl whisky in his glass. He put the glass on the carpet at his feet, crossed one knee over the other and tugged at his earlobe.

‘Did Lindsay put you up to this?’ he asked.

‘I don’t think she’s frightfully keen to leave you.’

‘Leave me?’ Arthur said.

‘She worries about your future.’

‘Good God! I’m not in my dotage yet, you know.’

‘She thinks you might be lonely.’

Arthur picked up the glass again. ‘Did she actually say that?’

‘Not in so many words, no.’

‘Ah, but you know her too well to be fooled, Eleanor.’

‘I’ve known her most of her life,’ Eleanor said.

She was hedging his questions skilfully so far and felt rather pleased with her deviousness. The ‘suggestion’ hadn’t come from Lindsay but from young Mr McCulloch who had enlisted her help when Lindsay was out of the room.

‘I’m not surprised that McCulloch wants to plunge helter-skelter into matrimony,’ Arthur said. ‘I expect he’ll want to take on a house of his own too.’

‘I think,’ Eleanor said, ‘that the young man may be more sensible than you give him credit for, sir.’

‘Well, he certainly isn’t short of a shilling or two,’ Arthur said. ‘At least he won’t be when he reaches his majority.’

‘Floating capital,’ Eleanor said, ‘looking for a berth?’

‘Perhaps I should offer to sell McCulloch this place and look out for something smaller and more suitable to my needs.’

This was precisely what Forbes McCulloch had warned her against.

‘I would not be able to accompany you, sir,’ Eleanor said.

‘What? Why ever not?’

‘I am unmarried.’

‘You’re unmarried now and nobody gives a fig.’

‘There is, or was, a child in the house.’

‘And that’s all that respectability requires, is it?’

‘Do you remember the sensation when Mr Fingleton employed a young housekeeper? What talk there was about that?’

‘Malicious gossip,’ Arthur said. ‘Nobody could ever prove that he was sleeping – that the young woman was anything other than she appeared to be. Besides, Ronald Fingleton was a notorious old rake and she was such a pretty young thing. No, no, no. There’s no comparison.’

‘Even so . . .’ said Eleanor, and let it hang.

Arthur sighed again and finished his whisky.

He was settled in now and would keep her talking for a good hour or more. She had laid out the hand, had planted the notion that he might lose her as well as his daughter and, with luck and a little manipulation in the course of conversation, she might discover just how much he valued her.

‘If this does come to pass,’ Arthur said, ‘he’ll have to pay his way.’

‘From what you’ve told me, sir, that would not be a problem.’

‘No, I don’t suppose it would,’ Arthur conceded. ‘It wouldn’t take much to convert this barn into two separate establishments. What’s up there? Five apartments?’

‘Yes, five.’

‘I’m not giving up my study.’

‘Lindsay would not expect you to.’

‘You have discussed this with her, haven’t you, Eleanor?’

‘In a general way, sir, yes.’

‘Well, if McCulloch does move into my house after marriage there’s one thing I would insist upon.’

‘No dogs?’ said Eleanor.

‘No mother-in-law,’ said Arthur.

Lindsay had never known what it was like to be other than prosperous. She accepted her position in society with the equanimity that is the birthright of all middle-class children. Money, like time, had had no real significance for her.

‘Live here?’ she said. ‘Papa would never stand for it.’

‘For a time, a year or two, while Forbes – your husband – establishes himself,’ Miss Runciman said. ‘Did I not hear you discuss some such thing with him yesterday afternoon?’

‘Did you? No, I think you’re mistaken,’ Lindsay said hesitantly.

‘Ah, in that case . . .’

‘Well, perhaps we did,’ said Lindsay, frowning.

She had been half asleep yesterday, particularly in the hour before dinner. She was under the impression that Forbes had been going on about the state of the war, particularly de Wet’s invasion of Cape Colony, details of which had just appeared in The Times. She had her own views about the war in South Africa but she did not have the temerity to argue her case with Forbes. Something less distant might have been said in the course of the evening, however. She tried to recapture the ebb and flow of the conversations that had marked out the dreary Sunday: some talk of money, much talk of marriage, a brief interlude of kissing – then what? She could not for the life of her recall.

‘I rather received the impression that you and Forbes were in agreement,’ Eleanor Runciman said.

‘About what?’

‘Marrying and coming to live here.’

‘Oh, did he say that? I mean, did I agree?’

‘I seem to remember,’ Eleanor went on, casually rather than cautiously, ‘that when Forbes said it might be an acceptable means of persuading your father that you aren’t too young to marry . . .’

‘Yes?’

‘You agreed with him.’

‘In that case,’ said Lindsay, ‘I suppose I must have. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I really must dash. I’m meeting Aunt Lilias in town at noon.’

‘Shopping?’

‘Lunching. Uncle Donald’s off somewhere working on a tender and my aunt’s feeling a little bit out in the cold.’

‘Poor soul,’ Miss Runciman said tactfully, and tactfully said no more.

‘Are you rich?’ Sylvie asked.

‘What makes you think that?’

‘Because you bring me here.’

Forbes looked round. It hadn’t occurred to him that the lounge of the Imperial Hotel in North Street was a particular haunt of the wealthy.

‘I bring you here because it’s convenient,’ Forbes said.

He was drinking tea in an effort to create the imp

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...