- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

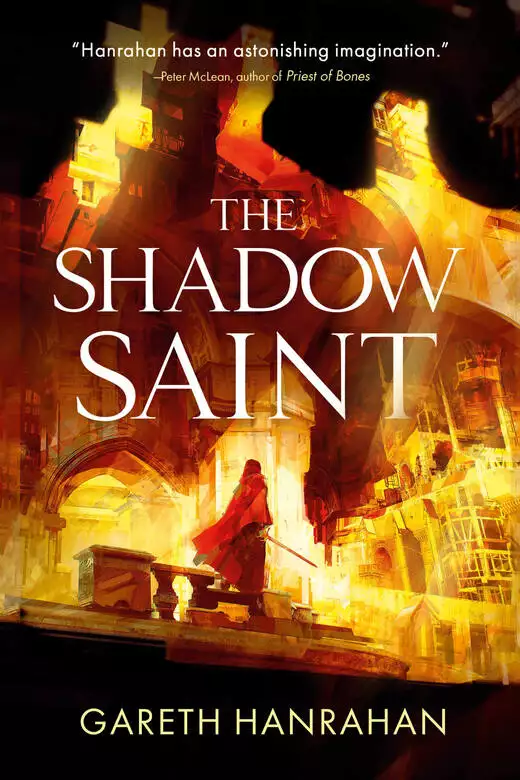

With his acclaimed debut, The Gutter Prayer, Gareth Hanrahan introduced a world of sorcerers and thieves, broken gods and dangerous magic. Now, this epic tale continues in The Shadow Saint, the gripping second novel in the Black Iron Legacy.

As the Godswar draws ever closer and tensions within the city escalate, how long will the people of Guerdon be able to keep their enemies at bay?

Release date: January 7, 2020

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 608

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Shadow Saint

Gareth Hanrahan

If Sanhada Baradhin had a son, the boy is dead.

But while the spy is not Sanhada Baradhin, and the boy in the cabin with him is not his son, for the duration of this voyage from the southlands to Guerdon he is Baradhin and the boy is Emlin. Eleven or twelve years old, maybe, but sometimes something far older looks out from his eyes.

The boy didn’t have a name when he was presented to the spy. They took his name away in the Paper Tombs.

Sanhada named him Emlin. It means ‘pilgrim’ in the tongue of Severast.

Taking on the roles of refugees from the Godswar was easy for both of them. Walk like you’re hollow. Keep your voice low, as though speaking too loud might attract the attention of some mad deity. Shudder when the weather changes, when light breaks through the clouds, when certain noises are too loud, too charged with significance. Flinch at portents. The man whose name is not Sanhada Baradhin and the boy who didn’t have a name arrived on board the steamer a week ago with bowed heads, shuffling up the gangplank with a crowd of other survivors. Sanhada’s contacts and god-wrought gold earned the pair a private cabin.

Taking on the roles of father and son is harder. Sanhada has no official standing in the Ishmere Intelligence Corps; nor is he a priest of Fate Spider. Nor, for that matter, was the spy ever a father before.

“I am chosen of the Fate Spider,” said Emlin on the first night at sea, when they were alone in the cabin. “Your fate has been woven for you. X84. The thread of your life is in my hands, and you shall obey me.” His adolescent voice broke as he recited the words they taught him in the temples. The boy’s small for his age. Dark hair, dark eyes, the pallor of years spent in the lightless Paper Tombs. He stood straight, with the pride of one who knew he’d been chosen by a god.

Sanhada had bowed his head solemnly, and said, “My life in your hands, little master–but outside this cabin, I am Sanhada Baradhin, and you’re my son. And I’ll thrash you if you speak out of turn.”

The boy frowned, his face flushed with anger, but before he could speak the spy added, “Live your cover, little master. It is pleasing to Fate Spider to keep secret that which is shadowed. No one outside this cabin shall know the truth, save you and I.”

And after that the spy saw secret pride in the boy’s face when he pretended to be Sanhada’s son.

Emlin, the spy hears, grew up in a monastery in Ishmere, although he’s not Ishmerian by birth. His family were killed in the Godswar; like many other war orphans, he was taken in by the church. In the morning, he tells the spy things he could not possibly know himself; the Fate Spider has been whispering in his ear as he slept, carrying intelligence reports from far away. No doubt there is another boy, or a blind old woman, or a young blade, or some other soul unlucky enough to be congruent with the deity, crouched in a prayer cell in the Paper Tombs, communing intelligence across the aether.

These reports are about the progress of the war, about advances and defeats. The Ishmeric armada has turned north.

Towards the land of Haith, Ishmere’s great rival, perhaps its last true danger. Towards Lyrix, the dragon-isle.

Guerdon, too, is in the north. Although Emlin never speaks of it directly, the spy infers that the gods of Ishmere are wary of challenging Guerdon directly. They fear the weapons that Guerdon birthed in the alchemists’ foundries, and worry that such god-killing tools might be wielded by other enemies, too.

In the privacy of their cramped cabin, the spy and the boy endlessly rehash their plans for reaching the city undetected, and what they will do when they get there. Neither of them has any knowledge of the intelligence corps’ plans for them once they arrive in the city, beyond making contact with the Ishmeric agents already in place. Emlin guesses that his role will be to relay information back to the fleet. For now, the spy is just a courier, tasked only with getting Emlin past Guerdon’s religious inspections. Foreign saints are forbidden in the city.

Sometime they eavesdrop on the conversations that filter down from the deck above. The spy paid extra to ensure he and Emlin have a private cabin, paid even more to ensure they’d be asked no questions. The pair remain mostly overlooked and forgotten.

Over breakfast on the fourth day out of Mattaur, Emlin asks him about Severast.

“Did you ever visit the temple of the Fate Spider there?” he says around a mouthful of fruit. He is always ravenous on waking.

The spy knows that Sanhada Baradhin visited that temple many times. The man was a smuggler, and the Spider is patron deity of thieves and liars as well as spies. Baradhin would visit the gaudy temple of the Many-Handed Goddess, the Severastian goddess of trade, and then stroll across the plaza and through the maze of alleyways in the medina, brushing past dancing girls, fire-eaters, smoke-seers, street vendors selling all manner of delights. The Spider’s temple in Severast was underground, hidden from view, connected to the surface by dozens of narrow winding staircases. Only one of these stairways was open at a time; to reach the temple, Sanhada Baradhin had to know which little shop in the medina was a front for the Fate Spider on a particular day. He bribed beggars to learn the secret of the streets.

“Once or twice,” admits the spy.

“It must have been glorious,” says Emlin, “before it became a den of thieves.”

“Thieves were always holy to the Spider in Severast.”

“Not in Ishmere,” declares Emlin emphatically. Reciting what he’s been taught.

No, thinks the spy. Not in Ishmere. The Fate Spider was worshipped in both lands, but in different ways. In Severast, he was a deity of the underworld, worshipped by the lost and the poor, the desperate and the disenfranchised. In Ishmere, in mad, cruel Ishmere, the Fate Spider was part of their militant pantheon, put into harness for the war effort. There, the Spider is a god of secrets, of prophecy and stratagems. God of endings, Fate-eater, poisoner of hope.

“The temple was beautiful,” admits the spy. “It was all veiled in shadow, each altar and shrine revealing itself only by touch. I—”

“I don’t see shadows,” interrupts Emlin. “All darkness is light to me.” His eyes gleam, and the spy realises he has never seen the boy stumble in the dim cabin. The fanatics of Fate Spider have robbed him of the beautiful gradations of shadow, of the softness of the dark, of the capacity for doubt.

That night, while the boy sleeps, the spy stays awake and remembers the fires of Severast. How the burning medina crashed and collapsed into the temple caverns below, the pale seers howling as the sunlight caught them. How all the delicious ambiguity of the temple was laid bare by the certainty of destruction. That night, while the boy sleeps, the spy watches him in the darkness and dreams of revenge.

Sanhada Baradhin is too long a name for the hasty Guerdonese, so the crew call him San. The ship’s name is Dolphin, and the spy can think of few names less fitting. Angry Metal Hippo or Ugly Floating Tub would be more appropriate. Driven by her roaring, stinking alchemical engines, she wallows with great enthusiasm through the waves, smashing her way across the ocean.

X84 is not the only passenger on the Dolphin; two dozen other people huddle on the deck, and there are more in the holds below. Most come from Severast; some from Mattaur or the Caliphates, or more distant lands. Some mutter prayers to defeated gods. Others are silent, hollow-eyed, looking to the empty horizon for meaning.

Ostensibly, Dolphin’s a freighter, not a passenger liner; when she left the docks of Guerdon, her hold was full of alchemical weapons. The ship is double-hulled with reinforced steel, warding runes half occluded by rust and barnacles, to ensure that her cargo of death was safe until it arrived. The spy wonders if that’s wholly necessary. The way the Godswar is going, the whole world will be consumed sooner or later, every living soul devoured in the hungers of the mad deities. If that’s the case, then what does it matter where the bombs go off? The only difference between a battlefield in Mattaur and some marketplace in Guerdon is a matter of time.

Time and money. The master of the ship makes great profit by selling bombs that explode on the battlefield, and would be greatly irritated if a bomb went off in a marketplace in Guerdon. It strikes the spy that the master is uniquely suited to his ship–both are singularly ugly, both approach the world as something to be smashed through, and both are wrapped in iron hulls to keep something toxic locked away. The master is named Dredger; at all times he wears a protective suit, a thing of valves and filters and tubes, so that not an inch of skin is exposed. His hands are heavy stubby-fingered gauntlets; his face is a mask of lenses, ports and wheezing bellows. The story among the crew is that Dredger has been exposed to so many alchemical weapons over the years that his flesh is thoroughly permeated by toxins, that he’d explode into a cloud of poisonous gas if he ever removed his containment suit.

Having observed Dredger for the last few days on the journey north to Guerdon, the spy has another theory–that there’s nothing wrong with Dredger at all, that the armour is a marketing gimmick. Certainly, it’s helped Dredger protect his niche of alchemical salvage, reusing the unthinkable weapons brewed up by the guilds of Guerdon. Who would want to get into a business when the cost is writ in the tormented flesh of the market leader?

Sanhada Baradhin did plenty of business with Dredger over the years, but the two never met. They corresponded by letter and courier, and the spy’s agents intercepted and read all those letters over the years. He feels as though he knows Dredger as well as Sanhada Baradhin did, that he has just as much claim to the man’s friendship. In Dredger’s eyes–lens-masked and hidden–the spy is Sanhada Baradhin, and that assumption is reality enough.

Dredger leans on the railing next to the spy. Some valve on his back hisses and spits steam as his pose relaxes a little.

“San,” he says, “have you given any thought to what you’re going to do when you get to Guerdon? I could probably find something for you, if you want.”

“What sort of work?”

“Nothing in the yards. Got Stone Men for that shit. No, I’m thinking maybe… sales? You must have contacts down south that ain’t dead, and if they ain’t dead, they’re buying, right?”

The spy considers the offer, weighing it, testing its balance like a fencer tests a sword. On the one hand, it’s a plausible next move for Sanhada Baradhin, and would provide him with a base of operations. On the other hand, he wants to get a feel for the city, and tying himself down to the first offer that comes his way is the wrong move. Racing straight towards his goal means sprinting into a minefield. He must approach obliquely.

“I’ve got some, ah, outstanding business to take care of first, my friend. And I was able to bring a little money out of Severast, so I’ll be all right for a few weeks. But thank you, and I might well take you up on it if the offer’s still open in a while.”

“Not like the war’s ending anytime soon.”

“Will there be a problem bringing money into the city?”

“Depends on whether or not you catch the eye of the customs inspectors. You’re not a man of faith, are you?”

“Not especially.”

Dredger points to another refugee, a middle-aged woman who has carried a number of small clay idols out of the sacked city. Bracing herself against the churning motion of the boat, she prays to them. Dancer and Kraken, Blessed Bol and Fate Spider. “They watch for foreign saints. They don’t much care in Guerdon which gods you pray to, so long as those gods don’t answer back,” says Dredger. “‘Specially not the gods of Ishmere.”

“The gods of Ishmere were the gods of Severast,” says the spy. “There were temples in Severast to the Lion Queen, too, and they did the rites just as faithfully there.”

A lens in Dredger’s helmet clicks and swivels, refocusing on the spy. “So what happened? Why’d the gods turn on Severast?”

“I’m not sure they did. There were saints of the Lion Queen on both sides, for a while. Those who say the gods are mad are right, I think, and mad people sometimes argue with themselves.” There’s a cloud in the distance that catches the spy’s attention. It’s moving against the wind. “And you can’t blame everything on the gods. If a runaway chariot runs over a child in the street, do you blame the charioteer or the horses?”

“I blame the parents,” mutters Dredger.

“Speaking of which,” says the spy, “the boy’s… a little god-touched. Your city watch–can they be bribed?”

There’s a gurgling sound from inside Dredger’s helmet, like he’s contemplatively suckling on the end of some tube. “Tricky, these days. Tricky.” He shakes his head. “And in my position, San, I can’t afford to piss off the watch by sneaking you into the city.”

He’s interrupted by one of the crew. “Master, there’s another ship off to the west. It’s a Haithi warship.” The sailor hands Dredger a telescope, and he inspects the distant ship.

“Keep on. We’ve no quarrel with them. And nothing worth confiscating on the return trip, eh?”

“See anything in that cloud?” asks the spy. Dredger swings the telescope around, peers at the dark smudge on the horizon.

“Not a thing. Why?”

“Just a feeling.”

The sound of praying voices grows louder. Several of the other refugees on deck gather around the woman with the clay icons. One of the icons is moving now, clay transmuting into scaly flesh. The tentacles of the Kraken break free of their earthy prison and thrash about on the deck. A collateral miracle.

“Dredger!”

“I see it! Turn! Turn!”

They’re too late. The cloud’s racing towards the Haithi warship now, and they’re caught right between the two belligerents. The Dolphin’s engines roar and belch smoke as they’re thrown to full power, but the blades can’t find purchase in the suddenly glassy water. A miracle has seized the waves, stealing them and claiming them for a hostile god. The water becomes unnaturally calm and clear for a mile in every direction, an icy track running from the stormcloud to the Haithi warship. Looking through the impossibly clear water, the spy can see all the way to the seabed a thousand fathoms below.

Tremendous tentacles writhe there, like the ones on the little clay icon but ten thousand times bigger.

“TURN!” roars Dredger. In a fury he snatches up the woman’s icons and hurls them overboard. They land on the surface of the sea and do not sink.

Emlin emerges onto the deck. “Go back down!” shouts the spy. “Stay below!” The boy retreats, half closing the door. Staring out at the transformed sea in wonder.

The Haithi warship is aware of the danger. She’s an older ship, a sailing frigate refitted as best they could for the perils of the Godswar. Rune-scored armour, proof against lesser miracles. Phlogiston shells loaded in her cannon. No doubt key crew members are Vigilant, their souls bound to their bodies, so they can fight on despite death and dismemberment. She turns to bring her guns broadside-on to the threat.

The storm crashes over and past the Dolphin. The glassy water is whipped into razor waves that scour the deck, shredding anyone caught in their path to red ribbons. The old woman was at the railing, reaching for her lost idols. She falls back, keening, her hands ruined and bloody. The wind laughs in his ears, and he glimpses a shape flitting through the sky overhead.

Of course. Somewhere up there is an Ishmeric saint, a locus of divine attention. Kraken and Cloud Mother are vast as the sea and the sky; the gods choose mortals as channels for their energies in the mortal realm. Dredger staggers across the deck, shouting at the helmsman. The storm’s passed them by, so if they can limp out of the afflicted patch of ocean, maybe they can get away intact. The Dolphin’s engines scream as the ship struggles in the water that is no longer water. A miracle of the Kraken. Still, they’re making a little progress—

—And then the Haithi ship is right on top of them, less than a spear’s throw away. The storm twists back on itself, pushing the Dolphin even closer to the warship. Cannons bark, and the spy throws himself to the deck as gunshots ring out over his head. To the credit of the Haithi gunners, not a single shot hits the Dolphin. Phlogiston shells burst in the storm clouds overhead, trailing blazing streamers as the alchemical substance burns mist and seawater and empty air alike.

The kraken rises, but there isn’t space for it to surface between the Dolphin and the Haithi warship. By closing the gap between the two vessels, the Haithi sailors have constrained their gigantic enemy, closing off one line of attack. They’re using Dredger’s ship as cover.

Gigantic tentacles rise out of the glass-smooth ocean on the far side of the Haithi ship, and the cannons on the other side answer in unison.

The Kraken-saint screams. One blazing tentacle sweeps across the Haithi deck, knocking sailors and cannons and anything else it can scrape off into the ocean. It leaves a slimy trail of burning phlogiston behind it. Haithi sailors rush to dump buckets of fire-quelling foam on the greenish flames, fighting alchemy with alchemy. Then the storm engulfs the two ships again, plunging them both into a laughing lightning-riven darkness and the spy can’t see the Haithi ship any more. There’s the occasional flicker of fire, but he can’t tell if that’s the ship catching fire or the muzzle flash of cannon.

The spy whispers into the wind: “I’m an Ishmeric spy. I’m on your side, you idiot. Back off!”

There’s no answer. He didn’t think there would be. His conscience, he decides, is clear.

Another tentacle explodes out of the ocean and swipes blindly for the Haithi warship. It finds the Dolphin instead and paws at the side of the ship, tearing a yard-wide hole just above the waterline. A cannon blast sprays burning liquid into the air. The spy’s lungs start to burn, and he coughs at the acrid smoke.

He stumbles across the deck in the direction that Dredger went. Climbs over the bodies of the other refugees–he can’t tell if they’re dead, clinging to the hull to avoid being thrown overboard, or just prostrate with divine terror. A short ladder leads up to a higher deck. He hears Dredger shouting orders, but there’s no time to explain himself. He sees a rifle in a rack and grabs it. Chambers a round, a little ampoule of alchemical blasting-power and lead.

Somewhere up there is the saint. The spy points his gun towards the heavens, looking for the heart of the storm.

There.

His shot strikes true. A human figure, held suspended by the clouds like an elemental trapeze, suddenly visible, suddenly twisted in agony. The figure tumbles, clutching at its side. The spy reloads, fires again, misses, reloads.

Mists thicken around the figure, slowing its descent, cradling it. The cloud reddens like a giant’s bandage as blood seeps into it, and as the cloud seeps into the saint’s body. A miracle of transmutation–the man will become more and more cloud, just as Captain Isigi is becoming more and more Lion Queen. That injury would be lethal to a mortal man, but a saint is more than mortal. It takes more than that to kill the earthly avatar of a god.

It takes, for example, a whole platoon of Haithi marksmen. Remorselessly accurate rifle fire targets the now exposed saint, shot after shot striking home. The Haithi gunners are Vigilant. Fear is only a memory to them. Undead limbs don’t tremble, and undead eye sockets don’t blink.

And then the saint falls. The storm breaks, unravelling with impossible speed as the natural order reasserts itself. The sea, too, is suddenly itself again as the Kraken-saint sinks away, releasing the waters from the grasp of its miracle. The Dolphin lurches forward, going from supernaturally becalmed to full acceleration in an instant. Even if they wanted to, it would be hard to circle back to the damaged Haithi warship, to the wounded but still dangerous kraken.

The Dolphin, after all, flies the flag of Guerdon, and Guerdon is neutral in this war.

Emlin cheers. The spy breathes again. He hands the weapon back to Dredger.

The armoured man takes the gun, methodically unchambers the last round, checks the barrel, weighs the odds. Then says:

“I’ll get your boy across safe, San. And then we’re square.”

“Just think of it,” says Dr Ramegos, “as building a bridge. Opening a door.”

Eladora Duttin nods, bites her lip to keep from stammering, then chants the spell Ramegos taught her. It’s not like opening a door, she thinks, it’s like pulling an anvil down on your head.

Eladora’s unprepared for this lesson in sorcery, but that’s true of this entire impromptu apprenticeship. She cannot quite recall when she first met Ramegos–sometime in the painful, chaotic haze after the Crisis. The days after that horror are lost in fog–Eladora vaguely remembers stumbling down from the Thay family tomb on Gravehill, body and soul wounded by her dead grandfather’s blasphemous sorceries. After that, there were weeks spent in a hospital bed, the metallic taste of the painkillers, and a succession of half-remembered grey figures who questioned her, over and over. Men from the city watch, from the church, the alchemists’ guild, from the emergency committee, all trying to piece together the events that had remade Guerdon. To take the broken, reeling city and give it an account of itself that made sense.

One of those figures never left Eladora’s side, and, over the weeks, resolved itself into a bright-eyed woman, too energetic to be as old as her wrinkled dark skin suggested. The endless interrogations and debriefings slowly became conversations and one-sided confessionals, and along the way Ramegos declared that she was going to teach Eladora sorcery.

Eladora extends her hand, feels the power flow along her arm. Feels the pain, anyway, and she assumes that means she’s channelling something. She clenches her fist, slowly, imagining the spell paralysing a target, holding them in unseen chains of sorcery–but then she loses control, the magic slipping through her fingers. For a moment, her hand feels like she’s thrust it into an open fire, the unseen chains suddenly turned to molten metal, her skin blistering. A spell gone awry can discharge unpredictably–if she swallows the power she’s drawn down, she can ground it inside her body, risking internal damage. If she lets it go, she might ignite something, and this cramped backroom in the IndLib’s parliamentary office is crammed with papers and books.

She holds her hand in the fire, trapped in indecision, until Ramegos leans forward and brushes away the errant spell as if it’s a cobweb clinging to her skin. The older woman’s casual use of power is impressive.

“That was a good attempt,” says Ramegos, “but sloppy. You’ve been neglecting your practice.”

“I-It’s been hard to find time. Mr Kelkin—”

“Kelkin will work us both to death if we let him.” Ramegos tosses a damp cloth at Eladora, who wraps it around her hand. “Not everything has to happen according to his schedule.”

It’s not his schedule, Eladora wants to protest, I’m working to fix Guerdon, and you’re… doing whatever a Special Thaumaturge does. But she doesn’t want to have that argument again. Ramegos may know, intellectually, what happened to this city, but she’s not from Guerdon. She doesn’t feel the same fierce urgency to save it that Eladora does.

She picks another conversational tack. “Whereas you intend to kill me at your leisure.”

“Sorcery,” says Ramegos, “is a perfectly healthy mental exercise, with only a small chance of self-immolation. If all you want out of life is wealth, power and sanity, go be an alchemist.” In the last century, Guerdon’s alchemical revolution has transformed the city–and the trade in alchemical weapons brought vast wealth in from overseas, as the Godswar consumes half the world.

I don’t want to be an alchemist. Or a politician’s adviser. Or…

“Now, again. But try not blowing yourself up this time.”

Eladora groans and tries to clear her mind, or at least brush aside a few of her more urgent worries. She lifts her hand again, envisages the twisting, impossible shapes—

And there’s a hammering at the door. Perik’s annoying voice shouting. “The chairman’s on his way! He’s called—”

He’s cut off abruptly. Eladora opens the door to reveal Perik’s stand there, frozen by the spell in the act of knocking. Ramegos snorts in amusement, dispels the paralysis with a wave of her hand. Perik’s standing there in confusion, caught in the action of knocking.

“—the committee,” finishes Perik. He glares at Eladora and would glare at Ramegos if he dared. The sorceress ignores him, picks up her heavy grimoire and hurries off, floating through the uproar of the outer office.

“Remember to practise your Khebeshi,” she instructs Eladora as she leaves. “You won’t get far as a sorcerer if your Khebeshi is poor.” Ramegos would say that–she’s from the distant city of Khebesh–and mastering the obscure and difficult tongue is very, very far down Eladora’s list of priorities.

Perik waits until Ramegos is gone before speaking. “Chairman Kelkin sent an aethergraph message an hour ago,” says Perik venomously, “he wants your report. I didn’t want to interrupt your time with the Special Thaumaturge.”

Eladora curses under her breath. She squeezes past Perik and hurries over to her desk in the outer office. A dozen other assistants to the emergency committee glance up at her, then return to their work, every one of them scribbling frantically like it’s the last minute of a final exam. The distant chatter of an aethergraph in another room; the hubbub of voices in the corridor, like a gathering wave. Kelkin’s nearly here.

She piles papers into her worn satchel, praying to no gods they’re in the right order. In her mind’s eye she can see Kelkin–her boss, everybody’s boss, chair of the emergency committee and de facto ruler of Guerdon–stomping up from Venture Square like a little puffing steam engine, dragging behind him a huge crowd of supplicants and clerks, beggars and bodyguards, lunatics and journalists, and heaven knows what else. When Kelkin appears in public these days, it’s always one breath away from a riot. Normally, Eladora’s nervous that something will happen when Effro Kelkin’s out and about in the city he temporarily rules. Today, she almost wants something to happen.

Anything to slow him down.

She’s not ready.

Eladora briefly wishes she’d been practising something more painful than a paralysis formula. Instead, all she can think to do is ask Perik for a favour. “Can you, ah, stall him? I just need five minutes.”

In truth, she needs five months.

Maybe five years.

The gigantic report on her desk is an inquiry into the origins, demographics, structure and status of the New City.

Ten months ago, at the height of what some call the Crisis and others the Gutter Miracle, a new city exploded into being within Guerdon. A warren of streets and tunnels, palaces and tower blocks, all made from pearly white stone, erupted from the corpse of a criminal named Spar and engulfed the south-east quadrant of Guerdon, inflicting untold damage on the Alchemists’ Quarter and the docks. Since then the New City has been colonised at speed. Refugees, mostly, but anyone brave enough could go down there and stake a claim to one of the empty palaces or the gleaming, silent arcades.

Guerdon was already reeling from a series of attacks; the city watch overstretched. There was no way to take control of the New City when it formed. The newspapers ran riot with lurid tales of depravity and crime. Anything’s possible there; even reality isn’t quite nailed down in the New City–her report is crammed with accounts of miracles and magic that she cannot attribute to any known god. There are cries and editorials demanding the New City be tamed, be purged, be quarantined or demolished or dispelled, but no one can agree on what should be done or how to do it.

Eladora’s impossible task was to understand the New City, to map it and take stock of it. Others on the Industrial Liberal staff were to build on her work, as part of the gre

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...