- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

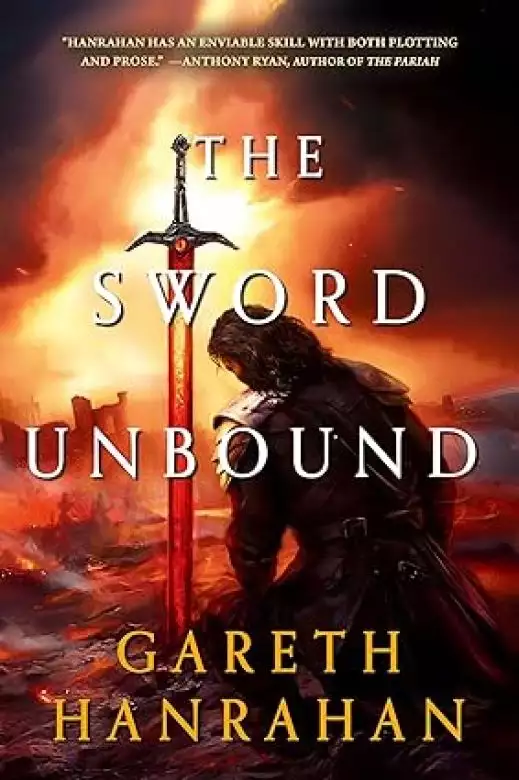

Gareth Hanrahan's acclaimed epic fantasy series of dark myth, daring warriors and bloodthirsty vengeance continues with The Sword Unbound.

He thought he was saving the world. That was his first mistake.

Twenty years ago, Alf and his companions defeated the Dark Lord and claimed his city. Now, those few of the Nine that remain find themselves unwilling rebels, defying the authority of both the mortal Lords they once served and the immortal king of the elves - the secret architect of everything they've ever known.

Once lauded as a mighty hero, Alf is now labelled a traitor and hunted by the very gods he seeks to bring down. As desperate rebellion blazes across the land, Alf seeks the right path through a maze of conspiracy, wielding a weapon of evil. The black sword Spellbreaker has found its purpose in these dark days. But can Aelfric remain a hero, or is his legend tarnished forever?

Praise for The Sword Defiant:

"A treat for all fantasy fans . . . . It’s an absolute blast.” ― Justin Lee Anderson, author of The Lost War

"In the tradition of Tolkien and Eddings, with a richly detailed narrative, well-drawn characters, epic battles, and political and religious intrigues, Hanrahan's outstanding first outing in the Lands of the Firstborn series will thrill fantasy readers—who will anxiously await the next book." ― Booklist (starred review)

"This novel has the potential to become a fan-favorite among those who appreciate vast and eloquent epic fantasy. Readers will enjoy the unique twists, absorbing intrigue, and endearing characters." ― Library Journal

"I will buy any novel that Gareth Hanrahan ever writes." ― The Fantasy Inn

For more from Gareth Hanrahan, check out:

The Black Iron Legacy

The Gutter Prayer

The Shadow Saint

The Broken God

Release date: May 7, 2024

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 560

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Sword Unbound

Gareth Hanrahan

She remembered putting her hand across a portion of the trunk, covering a few dozen lines, and thinking That’s it, that’s my span. Each ring had seemed so wide, each year so long. But they went quick.

A year ago, she’d held the Yule-feast in her house in Ersfel. Around the table she’d crowded a half-dozen of her tenants and labourers and their families. Last year, for the first time, she’d made Derwyn sit at the head. You’re of age now, she’d told him. You’re fifteen. And that made her think of the rings.

A year ago, she’d been the Widow Forster, the wife of the late Galwyn, Intercessors guard his soul. Prosperous, but those who envied what wealth she’d accrued had to admit that she’d paid a price. Her husband, her parents, her brothers – all dead. All but Alf, and Alf was gone. No one knew where.

But she’d known. She’d worked it out from the songs. A year ago, no one else in the village had guessed that big Alf had gone on to become Sir Aelfric Lammergeier, Hero of the Nine.

A year ago, Alf was dead to her, and she was – well, if not content, then at least safe.

A year ago, Derwyn had not died.

Now, she sat at a long table of polished marble with many guests, and ate from a plate of silver. Derwyn sat opposite her, picking at the fine food the servants brought him. His appetite had not come back with him, and there was a hollowness to his face she did not like.

Next to her was a place set for Alf, but it was empty. The last time she’d eaten with Alf at the Yule-feast… that must have been nearly twenty-five years ago, before he’d gone away adventuring on the Road.

Many miles and many years away.

Her guests that night were not farmhands and tenants, but worthies of Necrad – those who had not fled when it seemed the city was about to fall. She knew none of them, and they did not know her. It made for stilted conversation.

They called her Queen of Necrad, and she did not know how a queen of Necrad should talk. She smiled as they praised her, or talked about the fine wines or generous portions. The wine, certainly, was wonderful, for Lord Vond had left an excellent cellar. The portions of venison, less so – but considering their situation, even the wealthiest could not scorn a meal.

At the head of the table sat Derwyn. His face was flushed, his smile wide, but then he caught her eye from across the table and she could tell he was scared beneath the bravado. He took another cup of wine and drank deep – too deep, to her mind. Slow down.

She raised her own glass in a toast. “To the Uncrowned King,” she said.

“The Uncrowned King,” chorused the table. Olva sipped her wine carefully, and Derwyn mimicked her.

The Uncrowned King. That was what they called her son. Three months ago, her son had been a prisoner, hostage to a scheme against her brother. Derwyn had died in the dungeon under the city. But the wizard Blaise had opened a door to the grey lands of Death.

She’d gone through. She’d brought him back.

Blaise had warned he would not come back unchanged.

One of the merchants stared at her. She felt her cheeks burn beneath the Witch-Elf ceruse they’d made her wear. “Is something not to your liking—” Damnation, what was his name?

Somehow, Threeday heard the concern in her voice from the far end of the table. The pale creature tugged at one of the servants with boneless fingers. “Master Allard’s glass is empty. See to it.”

“—Master Allard?” finished Olva.

Allard shook his head, his gaze still fixed on her face. “Forgive me,” he said, “but I had to see for myself.” He lowered his voice. “I heard it rumoured that you were in fact the Lady Berys in disguise.”

Olva tried to suppress a laugh and half-choked on it. “You can see I’m not!”

“Still, strange things are whispered about you. That you are a Changeling, or an Intercessor in mortal form. That Blaise grew you in a vat.”

“I’m just flesh and blood. A simple Mulladale woman.” She looked around at the room. “I’m not used to playing host to such great lords.”

“But you were a guest of the late Prince Maedos. Guest of elves, kinswoman to heroes, mother to kings – hardly a common woman from the Mulladales.” Allard leaned closer. “I’ve heard it said, too, that Derwyn is the son of Peir the Paladin – that you birthed him in secret, and hid him away during the war.”

“My son’s father Galwyn Forster. He died in the war.” Her voice sharper than intended.

Allard flinched. “These are rumours from the streets. After miracles, people look for meaning. You and your son came from nowhere, appearing in our hour of need to save us. You say he is not Peir’s son, but I look at him and I see the Paladin returned. How else are we to read this riddle?”

“I—” I went into the Grey Lands. I went to Death’s kingdom, and I rescued my son. She wanted to boast, to give them a reason to support her. If the city turned on them, where would they go? “That is – it is true he was brought back from death, and he carries something of the Paladin in him.”

“The strangest of all the tales,” said Allard, in a tone of disbelief. “Truly, we live in a time of miracles.”

“It will be a miracle if we see next Yule,” grumbled another. He stared into his wine glass. “Here we sit, waiting for the noose. The Lammergeier declared rebellion when he murdered Prince Maedos, and the mad wizard runs unchecked, brewing up who knows what else in his tower! You say that boy and the Nine saved us from destruction? Saved us? We’re trapped!” He jabbed his finger at Derwyn. “If we support you, we defy the law of the Lords of Summerswell. If we don’t, we’re prisoners in this hellish city!”

Derwyn sprang up. “You don’t know what you’re talking about! We saved you all! Prince—”

Threeday called from the end of the table. “Master Pendel’s glass is empty again – but perhaps water might be more to his taste.”

“Damn it,” snapped Pendel, “let me at least get drunk.”

“Prince Maedos held my mother hostage and tortured me!” Derwyn slipped back his sleeve to reveal many scars. “My uncle saved us! Maedos deserved all that happened to him!”

“So you say,” said Pendel, “And even if all that’s true – may the Intercessors strike down those who bear false witness – what does it matter? Who outside Necrad will listen? Words don’t matter when it’s season for swords, and that’s what the thaw will bring. You’ve doomed us all.”

Olva interrupted him. “Derwyn, peace. And Master Pendel, if it’s talk of swords you want, then wait for my brother to return. Until then, my son’s words suffice. Now, this is a Yule-feast, not a council meeting. Fill your glass, and let’s be merry tonight.”

Wind rattled the shutters. The fortress might be sturdy, but it was damnably cold. Outside, Olva heard the last of the merchants departing, and breathed a sigh of relief. Derwyn sat down by the fireside. He looked haggard with the effort of playing the king. Some of it had been acting – Derwyn putting on airs, imitating stories she’d told about his father.

But not all of it.

“I’ll put more on the fire,” said Olva.

“It’s all right. Save the wood.” Derwyn gave her a wan smile. “Anyway, the servants would object to the queen soiling her hands.”

Olva snorted. Everything about that sentence was absurd. They’d inherited the Citadel’s serving staff – at least, the ones who hadn’t managed to flee Necrad during the siege. With nowhere else to go, unsure what to do, the servants continued to serve. They insisted on lighting the fires and cleaning the floors. They’d have dressed Olva if she’d let them.

And queen? Derwyn’s return had coincided with the awakening of the city’s magical defences. Somehow, overnight, a tale was told and retold in every corner of the city that her son was the destined king, a saviour come to right the wrongs of the world. That tale had united the ragged remnants of the city’s people. Mortal and Witch Elf, folk of the New Provinces and old – tales of the Uncrowned King were told among all of them.

Olva had her suspicions about who had planted those stories. Threeday, for one. He’d made himself indispensable to Alf and Blaise, just as he’d been indispensable to Timeon Vond.

Or Lord Bone.

It was all nonsense, but those stories protected her son, and for that she was grateful. And while she felt uncomfortable in Lord Vond’s palace it was better than anywhere else in Necrad. Why, here she could almost believe she was back south in Summerswell.

“I’ll put more on,” she repeated. She stood. Instantly there was a swarm of servants at the door.

“Permit me, my lady,” said a Vatling. He glided over to pile logs on the fire, the red light flushing his pale gelatinous face into something demonic. Others descended on the dining table, whisking away plates and glasses.

One hesitated over Alf’s untouched plate.

“Leave it,” said Derwyn. “He’ll be here.”

“And it’ll be cold when he arrives,” said Olva. “Take it and feed someone.”

“The cook told me it’s the last of the venison—”

“I know my brother. He’ll eat anything. As long as there’s bit of bread and something in the pot, Alf won’t notice. Take it, go on.”

“A feast fit for a hero,” said Derwyn. He laughed, then asked, suddenly subdued: “Will uncle Alf come back tonight?”

“He said he would.” They’d seen little of Alf since… since Derwyn had come back. The Lammergeier’s sword was needed everywhere. He was the last of the Nine left in the city – save Blaise, and the wizard was rarely seen outside his tower.

“Have you been sleeping any better?” she asked.

“A little. I keep waking myself up. I hear voices in my dreams.”

She’d heard him. Nightmares tormented her son. The first few nights, she’d gone to him when he woke screaming. All too often, she was awake herself, wracked by her own fears. But they both needed to live despite the shadow of the past.

“Sleep’s important. Sleep’s how you heal. I’ll ask Torun to have Blaise mix you up a potion.” Derwyn looked unconvinced, so she continued. “After your father died, old Widow Heather made me something to help me through the night. Everything that’s unsolvable and terrible in the small hours looks better by daylight.”

“It’s the light that keeps me from sleeping properly,” said Derwyn. “There’s no proper night here, nor daylight.” Even the tightest shutters failed to keep out the eerie glow of the necromiasma. “They’ll be lighting the fires in the holywood at home. There’ll be dancing after the Yule-feast.”

“Their feast won’t be a patch on ours,” said Olva.

“I wish we could see them. I wonder what Harlan’s doing now? Or Kivan? Or Quenna? Or even old Thomad?”

“Thomad,” said Olva, “had better be minding my farm, and I don’t care that it’s a feast-day. As for your friends, up to no good I expect.” A pang of homesickness struck her. It was not as though she was fond of any of Derwyn’s troublesome friends, but after meeting so many strangers and seeing such unearthly sights, she craved familiar faces.

“Quenna – she’d bought a comb from a trophy-monger at the fair. I said she looked as fair as a Witch Elf queen with her hair pinned back.”

“Did you now?”

“Well, I thought it. I was going to say it, but I got into a fight with Kivan instead.” He blushed, which put some welcome colour in his cheeks.

“You’ll see them again.”

“They wouldn’t believe any of this.”

“Which part?” asked Olva. “Us having the Yule-tide feast in a castle like great lords and ladies, or…” She waved at the window and the city beyond.

“Any of it.”

“Aye, well…” Olva took another glass of wine. “The rest of the world seems like a wild story if you never go down the Road. And you’re too young to remember the war, when the world came pressing in on us.”

An unfamiliar expression crossed Derwyn’s face, and he seemed about to speak, when another gust of wind blew the window open, the metal grille of the shutter clattering against the stone. Chill air carried with it the smell of the miasma. Olva went to close it.

She could see out over the rooftops of the Garrison district, the portion of the city claimed by the occupying forces of the League. The occupiers – human, dwarf, Wood Elf – had tried to make their enclave into an outpost of home, but succeeded only in making it grotesque. A gaudy mask hiding a monster’s face. Beyond the walls were the other portions of the city, the Liberties where the defeated Witch Elves dwelt, and the forbidden Sanction – although, after the siege, the Sanction was no longer secure. The guards that had once watched over its laboratories and temples were gone, dead or fled or withdrawn to the Garrison. Necrad hunched before her, a creature of slate and marble, flanks bristling with barbed spires and scaly rooftops, a thousand windowed eyes.

Through the vapours, she could see Blaise’s tower at the heart of the city. There, they had brought Derwyn back. The Wailing Tower and the Citadel were poised spears, keeping the monster at bay.

Olva reached out to close the shutter, conscious of the sheer drop below, the stout wall of the Citadel keep a four-storey cliff above a sprawl of lesser buildings. Looking down, she glimpsed a man clinging to the wall. A blade clenched in his teeth, cloak plastered to his body by the rain, fingers and toes digging into cracks in the mortar. For an instant, she stared at him in disbelief.

He saw her too. His eyes widened, and he scrambled up to scrabble at the windowsill. Olva grabbed at the shutter, but the – Thief? Assassin? Madman? – got one arm in before she could slam it shut. With a roar, the man shoved himself over, falling on top of her, down in a tangle of limbs. A stranger, hair cropped in a monk’s tonsure, eyes fixed not on her but on Derwyn. He held her down, his forearm across her collarbones, pinning her left hand, pressing against her throat. His other hand came up, and in it he had a delicate crossbow, elf-wrought, a wasp of polished steel with a barbed and deadly stinger.

Aimed at Derwyn.

Olva heaved herself up, surprising the attacker – and herself – with her strength. She knocked him over, and then she was on top of him, straddling him and punching him, slamming his right hand against the tiled floor until he lost his grip on the crossbow with a bone-snapping crack.

Derwyn was at her side then, a sword in his hand, the tip at the man’s throat. Her son’s hand shook, but his voice was steady. “Yield.”

“Not to you, abomination. Intercessors, receive my soul and carry—”

Olva snatched up the crossbow and struck the madman across the face. “Who sent you?”

“The grail-cup showed me your sins, mother of abomination. The Intercessors charged me with this holy mission. Know that I am the first of many. All of Summerswell stands against you!”

The Holy Intercessors, guardians of humanity. All her life, she’d been taught to see them as blessed spirits. The memory of Berys’ warning rang through her mind. It’s the Wood Elves. It’s always been the Wood Elves. The Church is theirs, too – the Erlking sent the Intercessors to watch us.

She pulled his head forward so her son could see the shaved pate. “A monk.” Olva scrambled to her feet and took the sword from Derwyn. She steeled herself to press the sword down, in case she needed to kill this man. Her hand did not waver. Where were the guards? How could this intruder have crept into the Citadel unchecked?

Derwyn leaned back against the windowsill. “You’re not from Necrad, then,” he said, and there was a strange timbre in his voice. “The Intercessors never answer prayers in this city.”

“I was an acolyte in Staffa when the Intercessors chose me.”

“I once thought they chose me, too, friend,” said Derwyn, but Olva could tell it wasn’t just her son. He came back from death, but not alone. “I was their champion, and I wielded the fire of the Intercessors from the High Moor to the gates of Necrad.”

“Peir the Paladin is dead,” spat the monk. “I have heard the lies they tell about you – that you claim to be Peir returned. The Intercessors told me the truth – that you are an abomination, as unholy as any horror spawned in the Pits of Necrad.”

“I do not know what I am,” said Derwyn. He spoke slowly, as if considering every word. “But the Intercessors could not aid me once I passed under the miasma. I entered the city alone, save for my companions.” He knelt down and touched the monk’s injured cheek. “But I found strength within me.” A light welled up in his hand, and the wound healed.

Olva stared at her son’s miracle.

The monk crawled away, his hand brushing against his cheek. “The Paladin returned?” He gasped in awe, all his righteous anger melting away into doubt. “Forgive me! I-I misread the signs!” He buried his face in Derwyn’s boots. “Forgive me,” he mumbled.

Olva grabbed the monk and dragged him away from Derwyn. The door across the room burst open and two guards rushed in, wearing the livery of the Citadel. “Milady, Lord Derwyn, are you both unhurt?”

“No thanks to you,” spat Olva. “Where were you when we called?”

The guards glanced at each other. “The door at the foot of the stairs was locked, milady,” said Winebald. “We had to break it down.”

She shoved the monk over to them. “Take him. Find out who locked that door. And search the Citadel – make sure there’s no one else out there. You’ll answer to the Lammergeier if anything else goes awry.”

“As you command, milady.” They bowed and departed, taking the monk with them.

Olva sank into her chair, suddenly sickened. She placed the crossbow on the table, next to her empty bowl.

Derwyn sat down too. He was pale, breathing heavily, but he was himself again, the eerie presence gone. “You use the same tone,” he said between gasps, “when giving out to the farmhands. At least when Cottar left the pigsty gate ajar, the pigs weren’t armed.”

“He tried to kill you.”

“I need to get used to that, don’t I?” Derwyn picked up his bowl and ate ravenously.

That night, Olva climbed the west tower. The moon beyond the necromiasma was full, so in the distance she could see the endless mudflats of the Charnel shimmering white with frost, and the black ribbon of the Road stretching away into the night. Soon, the spring thaw would make the Road navigable once more.

But she doubted she would ever go home again.

Beyond her sight, far far away – but linked by that very Road – lay the lands of Summerswell. There were maps in the Garrison, and she recalled them now: Arden in the Cleft with its high walls, Arshoth of the temples, wild Westermarch, the brave knights of the Riverlands, the mighty fleets of Ellscoast, old Ilaventur, the enchanted Eaveslands, the seat of the Lords in the Crownland, and even her beloved Mulladales. She recalled the perilous journey to Ellscoast, her terror at leaving home to chase Derwyn. The journey seemed unthinkable, but she now knew that it was only a tiny part of the lands of Summerswell.

Know that I am the first of many. All of Summerswell stands against you!

The monk said that, and Olva believed him. All the world she knew – all she could imagine – now stood against her family. Against her. Against Derwyn. And against Alf. The full might of Summerswell was aimed at them, and beyond Summerswell, the Everwood of the Elves, the heavenly Intercessors. The threat was greater than she could conceive, and she could not imagine how they might survive the coming year.

But felling the oak in the backfield was unthinkable too, until Alf chopped it down.

Prison gave Bor time to think.

He didn’t like it.

Thinking was wood-rot, eating away at his courage, making once-solid things frail and treacherous. Thinking was his sins coming back to him, and he had made mistakes enough to fill every one of the sixty nights he’d spent in this cell.

Thinking wasn’t a fit occupation for a man like him. Bor was a sellsword. Thinking on the battlefield got you killed. You practised until you acted without thinking, fought by instinct. That was his life.

Had been his life.

Now, he sat by the barred window and listened to the street below. He’d heard bells ring out wildly a few weeks ago – not a summons to prayer, not to mark the approach of Yuletide, but an alarm, a warning. Then shouting in the streets, and later, many feet marching. Horses, too, and the jangle of armour. Troops mustering for war.

He should be down there. There was money in war, especially if you were a survivor like Bor. Stay clear of the battles, stay clear of the cursed magic, and take coin from the desperate. In times of chaos, thinkers were at a disadvantage.

Now all he could do was sit here.

Thinking.

Rotting.

Where were they marching? Was there a quarrel between the Lords of Summerswell? Trouble on the Westermarch? Or north? If there were soldiers marching through the Crownland, then something big was afoot, on the scale of Lord Bone’s war a generation ago.

And he was out of it.

If he wasn’t careful, his thoughts would turn to how he came to be here, and those thoughts were bad. He’d have to remember what he’d done. He’d have to remember he was damned, that the Holy Intercessors had come down and judged him and condemned him to this cell.

An angel smote him in an alleyway.

There was nothing here to distract him from thoughts of damnation. A barred window that looked out over an empty yard, the snowfall of three weeks ago unmarred by footprints. A narrow bed, a thin blanket. A piss-pot in the corner. A locked door.

And a stool for the interrogators.

There had been plenty of questions in those first days. Cold-eyed and nameless, demanding answers he couldn’t give. They’d asked him about his meeting with the Lammergeier at the Highfield Fair, and how the Lammergeier had commanded that Bor bring a message to his sister. Demanded he describe everything he could recall about the hero, about the black sword he bore, about those who spoke to the Lammergeier afterwards. They talked as though they suspected Bor of lying – and that, he thought, was utter nonsense. What would it profit him to lie about meeting a great hero like the Lammergeier? More to the point, why would he give a fortune in coin to some woman he’d never met?

Their questions were like the seeds of thorn bushes planted in his brain. They’d ask him a question he couldn’t answer – like What was in the Lammergeier’s letter to Olva Forster? – and afterwards, in the night, his thoughts would fester. His brain would get caught trying to work out what the answer might be, or why it was important. He’d told them, over and over, that he knew nothing.

Maybe they’d believed him, because no one had come to his cell in weeks.

He had, of course, tried to escape.

The first time, he just acted. The servant fumbled when trying to bolt the door, and Bor pounced like a wildcat, yanking the door open and smashing the servant against the wall. He’d nearly made it out of the tower before darkness claimed him. He remembered being unable to breathe, and grey eyes, and pain, and nothing.

Then the cell again.

The second time, he planned it as well as Bor had ever planned anything. He tested every element of his cell – looked for loose stones, tried to pull the bars from the mortar, tried to lift the door off its hinges – until finally, he found the answer. It was the week of the Feast of the First Grail, the holy day marking when the Erlking revealed the Intercessors to the first Lords of Summerswell. It was among the highest of festivals, and every pious soul was obliged to go and give thanks for their salvation.

Bor’s plan was this: first, he fashioned a knife from a broken chair, and hid it in his boot. Then, when the servant came, Bor demanded that he be allowed to attend church on the morrow. They could not deny his request, after all. Then, when the moment was right, he would draw the knife, put it to the throat of the priest. No one would risk spilling the blood of a cleric on holy ground. He’d demand a horse, and he’d drag the priest with him until he was sure no one had pursued him, and then he would ride away.

It was, by Bor’s standards, an intricate plan.

It lasted six heartbeats.

The morning of the feast-day, the door to the cell was opened not by the mute servant, but by a grey-eyed interrogator. She kicked Bor in the groin. He doubled over, and she plucked the shank from his boot.

“If you are a fool,” she said, “try again.”

Then she hauled him out of the tower and brought him to the nearest chapel. She sat next to him and made him listen while the priest celebrated the Feast of the First Grail, and the people gave thanks for the kindness of the Intercessors. All the while, she kept Bor’s own knife pressed against his ribs.

After, she brought him back to the tower, and locked the door. He did not see her or any of the other interrogators again. So he sat there, with nothing to do except contemplate his own damnation.

After an eternity, a visitor.

It was not the servant, nor the cold-eyed inquisitor. His visitor came huffing up, walking stick tapping on the spiral steps. He was sixty at least, red-cheeked, squeezing his bulk through the narrow door of the cell. He sagged onto the creaking bed and waved at Bor to take the stool while he mopped his brow with a handkerchief.

The old fool had left the door open.

Bor didn’t think. He acted. He leaped for the doorway—

–—and crashed heavily to the ground as the old man speared Bor’s ankle with his cane.

“If you’d—” the old man gasped for breath “—wait a moment, I have a proposition for you. One far more profitable than another ill-considered escape attempt.”

Bor picked himself up with a groan. “Who the fuck are you?”

The stranger looked around the cell. “We’ll have to get you moved somewhere more salubrious. I’d never fit a writing desk in here. I know I did my best work in a prison cell, but it was a damn sight more comfortable than this. You don’t even have a wine rack, for heaven’s sake.”

“Who. The fuck. Are you?”

“Oh, a humble storyteller. I was a knight, once.” The man slapped his belly. “But now I wield a pen instead. Call me Rhuel.”

“Rhuel,” repeated Bor. “Sir Rhuel of Eavesland!?”

“Bless you, my boy. It’s always gratifying to be recognised.”

“You wrote The Song of the Nine!”

“I did. From a cell much like this one, in fact. Though at least I had the sense to try to force myself on a pretty maiden, not Sir Lammergeier’s dried-up old sister.”

Bor struggled to his feet. “That’s not how it happened! Olva – the Lammergeier’s sister – hired me to help find her missing son. But he was beyond rescue. I told her to go home, but she wouldn’t listen. She’d have gotten herself killed if I hadn’t… if I hadn’t…”

“Betrayed her? Given her into the hands of her enemies?”

Bor hung his head. “Aye.”

“Well, you can forget all that, my boy. Put aside your guilt. It makes for a sad story. No, what we need here is something much more entertaining. Blood and lust and peril, not the maundering of a sellsword.” Sir Rhuel produced a quill and a sheet of paper. “Let’s start again. Tell me your tale, Bor the Rootless.”

“I don’t understand what you want of me.”

“It’s quite simple, my boy. Twenty years ago, I was in another prison, and my cell overlooked the stables. I got all the gossip from the lord’s messengers when they changed horses. I heard wild rumours about a band of adventurers, and it caught my imagination. I wrote down those rumours, collated them, expanded on them. Added some poetic flourishes. I sold my first manuscripts through the bars of my cell for a penny a sheet.” He smiled fondly. “I found patronage. In time, my writings won me a pardon. The Nine might have saved the world, Bor, they won the war and slew Lord Bone, but their deeds are nothing without my words. I made them heroes in the hearts of the commoners, you see.”

He picked up the pen again. “And now, I have a new patron and a new commission. Or rather, we do. I shall write, and your testimony shall give it the ring of truth.” He pointed the quill at Bor. “I made the Nine into heroes. But what I must give the groundlings now, friend, is a villain.”

Bor had thought he’d never be warm again, the way the wind whipped through the narrow bars of his cell. This inn had a fireplace big enough to roast a sheep, and he contemplated climbing inside it to burn the chill from his bones.

“A bad winter, indeed,” remarked Sir Rhuel from his desk. “As bad as the Hopeless Winter, maybe? Or is that hyperbolic? No, no, this is for the commoners – they eat up references to the old stories. I’ve grown cautious.” Rhuel leaned towards Bor and spoke in a stage whisper. “You see, lately, I’ve been writing mostly for the Lords, and they sometimes have Wood Elves as guests in their halls. And elves are bastards when it comes to literary criticism. You make some o

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...