- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Not Yet Available

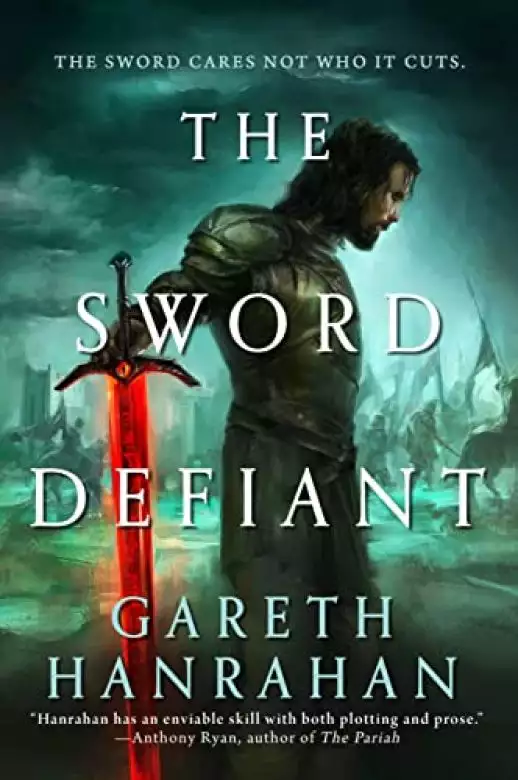

Release date: May 2, 2023

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 560

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

The Sword Defiant

Gareth Hanrahan

His story had not begun in a tavern, but Alf had ended up in one anyway.

“An ogre,” proclaimed the old man from the corner by the hearth, “a fearsome ogre! Iron-toothed, yellow-eyed, arms like oak branches!” He wobbled as he crossed the room towards the table of adventurers. “I saw it not three days ago, up on the High Moor. The beast must be slain, lest it find its way down to our fields and flocks!”

One of the young lads was beefy and broad-shouldered, Mulladale stock. He fancied himself a fighter, with that League-forged sword and patchwork armour. “I’ll wager it’s one of Lord Bone’s minions, left over from the war,” he declared loudly. “We’ll hunt it down!”

“I can track it!” This was a woman in green, her face tattooed. A Wilder-woman of the northern woods – or dressed as one, anyway. “We just need to find its trail.”

“There are places of power up on the High Moor,” said a third, face shadowed by his hood. He spoke with the refined tones of a Crownland scholar. An apprentice mage, cloak marked with the sign of the Lord who’d sponsored him. He probably had a star-trap strung outside in the bushes. “Ancient temples, shrines to forgotten spirits. Such an eldritch beast might…”

He paused, portentously. Alf bloody hated it when wizards did that, leaving pauses like pit traps in the conversation. Just get on with it, for pity’s sake.

Life was too short.

“… be drawn to such places. As might other… legacies of Lord Bone.”

“We’ll slay it,” roared the Mulladale lad, “and deliver this village from peril!”

That won a round of applause from the locals, more for the boy’s enthusiasm than any prospect of success. The adventurers huddled over the table, talking ogre-lore, talking about the dangers of the High Moor and the virtues of leaving at first light.

Alf scowled, irritated but unable to say why. He’d finish his drink, he decided, and then turn in. Maybe he’d be drunk enough to fall straight asleep. The loon had disturbed a rare evening of forgetfulness. He’d enjoyed sitting there, listening to village gossip and tall tales and the crackling of the fire. Now, the spell was broken and he had to think about monsters again.

He’d been thinking about monsters for a long time.

The old man sat down next to Alf. Apparently, he wasn’t done. He wasn’t that old, either – Alf realised he was about the same age. They’d both seen the wrong side of forty-five winters. “Ten feet tall it was,” he exclaimed, sending spittle flying into Alf’s tankard, “and big tusks, like a bull’s horns, at the side of its mouth.” He stuck his fingers out to illustrate. “It had the stink of Necrad about it. They have the right of it – it’s one of Bone’s creatures that escaped! The Nine should have put them all to the sword!”

“Bone’s ogres,” said Alf, “didn’t have tusks.” His voice was croaky from disuse. “They cut ’em off. Your ogre didn’t come out of Necrad.”

“You didn’t see the beast! I did! Only the Pits of Necrad could spawn such—”

“You haven’t seen the sodding Pits, either,” said Alf. He felt the cold rush of anger, and stood up. He needed to be away from people. He stumbled across the room towards the stairs.

Another of the locals caught his arm. “Bit of luck for you, eh?” The fool was grinning and red-cheeked. Twist, break the wrist. Grab his neck, slam his face into the table. Kick him into the two behind him. Then grab a weapon. Alf fought against his honed instincts. The evening’s drinking had not dulled his edge enough.

He dug up words. “What do you mean?”

“You said you were going off up the High Moor tomorrow. You’d run straight into that ogre’s mouth. Best you stay here another few days, ’til it’s safe.”

“Safe,” echoed Alf. He pulled his arm free. “I can’t stay. I have to go and see an old friend.”

The inn’s only private room was upstairs. Sleeping in the common room was a copper a night, the private room an exorbitant six for a poky attic room and the pleasure of hearing the innkeeper snore next door.

Alf locked the door and took Spellbreaker from its hiding place under the bed. The sword slithered in his grasp, metal twisting beneath the dragonhide.

“I could hear them singing about you.” Its voice was a leaden whisper. “About the siege of Necrad.”

“Just a drinking song,” said Alf, “nothing more. They didn’t know it was me.”

“They spoke the name of my true wielder, and woke me from dreams of slaughter.”

“It rhymes with rat-arsed, that’s all.”

“No, it doesn’t.”

“It does the way they say it. Acra-sed.”

“It’s pronounced with a hard ‘t’,” said the sword. “Acrai-st the Wraith-Captain, Hand of Bone.”

“Well,” said Alf, “I killed him, so I get to say how it’s said. And it’s rat-arsed. And so am I.”

He shoved the sword back under the bed, then threw himself down, hoping to fall into oblivion. But the same dream caught him again, as it had for a month, and it called him up onto the High Moor to see his friend.

The adventurers left at first light.

Alf left an hour later, after a leisurely breakfast. Getting soft, he muttered to himself, but he still caught up with them at the foot of a steep cliff, arguing over which of the goat paths would bring them up onto the windy plateau of the High Moor. Alf marched past them, shoulders hunched against the cold of autumn.

“Hey! Old man!” called one of them. “There’s a troll out there!”

Alf grunted as he studied the cliff ahead. It was steep, but not insurmountable. Berys and he had scaled the Wailing Tower in the middle of a howling necrostorm. This was nothing. He found a handhold and hauled himself up the rock face, ignoring the cries of the adventurers below. The Wilder girl followed him a little way, but gave up as Alf rapidly outdistanced her.

His shoulders, his knees ached as he climbed. Old fool. Showing off for what? To impress some village children? Why not wave Spellbreaker around? Or carry Lord Bone’s skull around on a pole? If you want glory, you’re twenty years too late, he thought to himself. He climbed on, stretching muscles grown stiff from disuse.

At the top, he sat down on a rock to catch his breath. He’d winded himself. The Wailing Tower, too, was nearly twenty years ago.

He pulled his cloak around himself to ward off the breeze, and lingered there for a few minutes. He watched the adventurers as they debated which path to take, and eventually decided on the wrong one, circling south-east along the cliffs until they vanished into the broken landscape below the moor. He looked out west, across the Mulladales, a patchwork of low hills and farmlands and wooded coppices. Little villages, little lives. All safe.

Twenty years ago? Twenty-one? Whenever it was, Lord Bone’s armies came down those goat paths. Undead warriors scuttling down the cliffs head first like bony lizards. Wilder scouts with faces painted pale as death. Witch Elf knights mounted on winged dreadworms. Golems, furnaces blazing with balefire. Between all those horrors and the Mulladales stood just nine heroes.

“It was twenty-two years ago,” said Spellbreaker. The damn sword was listening to his thoughts again – or had he spoken out loud? “Twenty-two years since I ate the soul of the Illuminated.”

“We beat you bastards good,” said Alf. “And chased you out of the temple. Peir nearly slew Acraist then, do you remember?”

“Vividly,” replied the sword.

Peir, his hammer blazing with the fire of the Intercessors. Berys, flinging vials of holy water she’d filched from the temple. Gundan, bellowing a war cry as he swung Chopper. Gods, they were so young then. Children, really, only a few years older than the idiot ogre-hunters. The battle of the temple was where they’d first proved themselves heroes. The start of a long, bitter war against Lord Bone. Oh, they’d got side-tracked – there’d been prophecies and quests and strife aplenty to lead them astray – but the path to Necrad began right here, on the edge of the High Moor.

He imagined his younger self struggling up those cliffs, that cheap pig-sticker of a sword clenched in his teeth. What would he have done, if that young warrior reached to the top and saw his future sitting there? Old, tired, tough as old boots. Still had all his limbs, but plenty of scars.

“We won,” he whispered to the shade of the past, “and it’s still bloody hard.”

“You,” said the sword, “are going crazy. You should get back to Necrad, where you belong.”

“When I’m ready.”

“I can call a dreadworm. Even here.”

“No.”

“Anything could be happening there. We’ve been away for more than two years, moping.” There was an unusual edge to the sword’s plea. Alf reached down and pulled Spellbreaker from its scabbard, so he could look the blade in the gemstone eye on its hilt and—

—Reflected in the polished black steel as it crept up behind him. Grey hide, hairy, iron-tusked maw drooling. Ogre.

Alf threw himself forward as the monster lunged at him and rolled to the edge of the cliff. Pebbles and dirt tumbled down the precipice, but he caught himself before he followed them over. He hoisted Spellbreaker, but the sword suddenly became impossibly heavy and threatened to tug him backwards over the cliff.

One of the bastard blade’s infrequent bouts of treachery. Fine.

He flung the heavy sword at the onrushing ogre, and the monster stumbled over it. Its ropy arms reached for him, but Alf dodged along the cliff edge, seized the monster’s wrist and pulled with all his might. The ogre, abruptly aware of the danger that they’d both fall to their deaths, scrambled away from the edge. It was off balance, and vulnerable. Alf leapt on the monster’s back and drove one elbow into its ear. The ogre bellowed in pain and fell forward onto the rock he’d been sitting on. Blood gushed from its nose, and the sight sparked unexpected joy in Alf. For a moment, he felt young again, and full of purpose. This, this was what he was meant for!

The ogre tried to dislodge him, but Alf wrapped his legs around its chest, digging his knees into its armpits, his hands clutching shanks of the monster’s hair. He bellowed into the ogre’s ear in the creature’s own language.

“Do you know who I am? I’m the man who killed the Chieftain of the Marrow-Eaters!”

The ogre clawed at him, ripping at his cloak. Its claws scrabbled against the dwarven mail Alf wore beneath his shirt. Alf got his arm locked across the ogre’s throat and squeezed.

“I killed Acraist the Wraith-Captain!”

The ogre reared up and threw itself back, crushing Alf against the rock. The impact knocked the air from his lungs, and he felt one of his ribs crack, but he held firm – and sank his teeth into his foe’s ear. He bit off a healthy chunk, spat it out and hissed:

“I killed Lord Bone.”

It was probably the pain of losing an earlobe, and not his threat, that made the ogre yield, but yield it did. The monster fell to the ground, whimpering.

Alf released his grip on the ogre’s neck and picked up Spellbreaker. Oh, now the magic sword was perfectly light and balanced in his hand. One swing, and the ogre’s head would go rolling across the ground. One cut, and the monster would be slain.

He slapped the ogre with the flat of the blade.

“Look at me.”

Yellow terror-filled eyes stared at him.

“There are adventurers hunting for you. They went south-east. You, run north. That way.” He pointed with the blade, unsure if the ogre even spoke this dialect. It was the tongue he’d learned in Necrad, the language the Witch Elves used to order their war-beasts around. “Run north!” he added in common, and he shoved the ogre again. The brute got the message and ran, loping on all fours away from Alf. It glanced back in confusion, unsure of what had just happened.

Alf lifted Spellbreaker, glared into the sword’s eye.

“I was testing you,” said the sword. “You haven’t had a proper fight in months. Tournies don’t count – no opponent has the courage to truly test you, and it’s all for show anyway. Your strength dwindles. My wielder must—”

“I’m not your bloody wielder. I’m your gaoler.”

“I am bored, wielder. Two years of wandering the forests and backroads. Two years of hiding and lurking. And when you finally pluck up the courage to go anywhere, it’s to an even duller village. I tell you, those people should have welcomed the slaughter my master brought, to relieve them of the tedium of their pathetic—”

“Try that again, and I’ll throw you off a cliff.”

“Do it. Someone will find me. Something. I’m a weapon of darkness, and I call to—”

“I’ll drop you,” said Alf wearily, “into a volcano.”

Last time, they’d reached the temple in two days. He’d spent twice as long already, trudging over stony ground, pushing through thorns and bracken, clambering around desolate tors and outcrops of bare rock. He’d known that finding the hidden ravine of the temple would be tricky, but it took him longer than he’d expected to reach Giant’s Rock, and that was at least a day’s travel from the ravine.

That big pillar of stone, one side covered with shaggy grey-green moss – that was Giant’s Rock, right? In his memory it was bigger. Alf squinted at the rock, trying to imagine how it might be mistaken for a hunched giant. He’d seen real giants, and they were a lot bigger.

If this was Giant’s Rock, he should turn south there to reach the valley. If it wasn’t, then turning south would bring him into the empty lands of the fells where no one lived.

Maybe they’d come from a more northerly direction, last time. He walked around the pillar of stone. It remained obstinately un-giant-like. No one ever accused Alf of having the soul of a poet. A rock pile was a rock pile to him. The empty sky above him, the empty land all around. He regretted letting that ogre run off; maybe he should have forced it to guide him to the valley. Turn south, or continue east?

The valley was well hidden. There’d been wars fought in these parts, hundreds of years ago, in the dark days after… after… after some kingdom had fallen. The Old Kingdom. Alf’s grasp of history was as good as could be expected of a Mulladale farm boy who’d could barely write his name, and nearly thirty years of adventuring hadn’t taught him much more. Oh, he could tell you the best way to fight an animated skeleton, or loot an ancient tomb, but “whence came the skeleton” or “who built the tomb” were matters for cleverer heads. He remembered Blaise lecturing him on this battlefield, the wizard wasting his breath on talking when he should have been keeping it for walking. Different factions in the Old Kingdom clashed here. Rival cults, Blaise told him, fighting until both sides were exhausted and the Illuminated were driven into hiding. The green grass swallowed up the battlefields and the barrow tombs, and everything was forgotten until Lord Bone had called up those long-dead warriors. Skeletons crawled out of the dirt and took up their rusty swords, and roamed the High Moors again.

Last time, Thurn the Wilder led them. He could track anything and anyone, even the dead. He’d brought them straight to the secret path, following Lord Bone’s forces into the hidden heart of the temple. All Alf had to do was fight off the flying dreadworms sent to slow them down. Even then, Acraist had seen that the Nine of them were dangerous.

“No, he didn’t,” said the sword. It was the first time it had spoken since the cliff top.

“Stop that.”

“If Acraist thought you were a threat, he’d have sent more than a few riderless worms. He was intent on breaking the aegis of the temple, not worrying about you bandits. You were an irrelevant nuisance. You got lucky.”

“Well, he got killed. And so did Lord Bone, and you can’t say that was luck.”

A quiver ran through the sword. The blade’s equivalent of a derisive snort.

He took another step east, and the sword quivered again.

“What is it?”

“Nothing, O Lammergeier,” said Spellbreaker sullenly. Alf hated that nickname, given to him in the songs by some stupid poet drunk on metaphor. He’d never even seen one of the ugly vultures of the mountains beyond Westermarch. They were bone-breaking birds, feasters on marrow. And while Alf might be old and ugly enough now to resemble a vulture, the bloody song had given him that name twenty or so years ago. He’d broken Bone, hence – Sir Lammergeier.

Poetry was almost as bad as prophecy.

The sword only used the name when it wanted to annoy him – or distract him. What had that pretentious apprentice said in the inn, about creatures of Lord Bone sensing places of power? Alf drew the sword again and took a step forward. The jewelled eye seemed to wince, eldritch light flaring deep within the ruby.

He shook Spellbreaker. “Can you detect the temple?”

“No.”

Another step. Another wince.

“You bloody well can,” said Alf.

“It’s sanctified,” admitted Spellbreaker reluctantly. “Acraist protected me from the radiance, last time.”

Alf looked around at the moorland. No radiance was visible, at least none he had eyes to see.

“Well then.” He set off east, and only turned south when prompted by the twisting of the demonic sword.

Another day, and the terrain became familiar. Some blessing in the temple softened the harshness of the moor. Wildflowers grew all around. Streams cascaded down the rocks, chiming like silver bells. Alf felt weariness fall from his bones, sloughing away like he’d sunk into a warm bath.

Spellbreaker shrieked and rattled in its scabbard.

“It’s too bright. I cannot go in there. It will shatter me.”

“I’m not leaving you here.”

“Wielder, I cannot…”

Alf hesitated. Spellbreaker was among the most dangerous things to come out of Necrad, a weapon of surpassing evil. It could shatter any spell, break any ward. In the hands of a monster, it could wreak terrible harm upon the world. Even that ogre could become something dangerous under the blade’s tutelage. But maybe the sword was right – dragging it into the holy place might damage it. When they’d fought Acraist that first time, down in the valley, the Wraith-Captain wasn’t half as tough as when they battled him seven years later. The valley burned things of darkness.

Would it burn Alf if he carried the sword down there?

“Look,” sneered Spellbreaker. “You’re expected.”

A tiny candle flame of light danced in the air ahead of Alf. And then another kindled, and another, and another, a trail of sparks leading down into the valley.

Alf drew the sword and drove it deep into the earth. “Stay,” he said to it, scolding it like a dog.

Then down, into the hidden valley of the Illuminated One.

Rubble lay strewn across the valley. Acraist had shattered the temple arch before they’d arrived. Alf remembered the headlong race down the path, hastening to intervene before the Wraith-Captain slew the Illuminated One. Laerlyn leaping gracefully down the rocks, loosing arrows as she ran. Jan weeping even as she called on the Intercessors to shield them from Acraist’s death-spells. Miracles warring with dark magic in the air.

In retrospect, the greatest miracle was that none of them had tripped and broken their necks as they ran down the steep path into the valley. The little sparkling lights led Alf along the safest route, until he reached the valley floor. Then they shot off ahead of him, meteors racing over the rubble, dodging in and out of hiding places. There was something playful about their movements.

The Sanctum of the Illuminated One – another thing wizards did was Audibly Pronounce Capital Letters – was carved out of the rock of the canyon. Pillars covered with twining glyphs bore images of godly figures Alf didn’t recognise. One was a woman, her face so worn nothing of her features remained, although Alf could still make out chains carved on her wrists. Opposite her was a horned figure holding a staff, arcane sigils in an arc above him. He remembered Jan and Blaise had yammered about how bloody old the temple was – older than any shrine in Summerswell, even the big one in Arshoth.

If they liked old stuff, they’d love Alf now. Forty-five summers by the reckoning of the south, but Necrad didn’t have proper summers, or proper time, so who knew how old he was. He felt as ancient as the toppled statues around him.

He followed the lights, and they led him towards a hut of piled stones.

Jan sat waiting at the entrance.

She’d become thin – so thin he could see the hut through her, as though she was made of coloured glass. The little lights ran to her, flowed into her, and he could see them now like stars through the window of her body. She smiled at him, and it was like looking at a radiant sunset. Still, he shivered at the sight. They’d all changed so much.

The rest of the Nine had, anyway. Alf remained Alf.

“Hello, Aelfric,” said Jan.

“I got the dream you sent.”

She nodded. “And it guided you here.”

“Guided ain’t the way I’d put it, but aye.” He paused, awkwardly. He’d loved Jan, they all did, the little mouse of the Nine, but he’d never claimed to understand her. “Should I kneel?”

“Just sit, Alf. Holiness isn’t in your knees.”

Alf settled awkwardly opposite Jan. He found himself holding his breath, as if exhaling too forcefully might blow away the gossamer of her existence. “Jan… what happened to you?” Last time he’d seen her was when she left Necrad a decade ago. Then, she’d been exhausted by her work in the city. Angry, too – simmering, bitter, her kindness worn down until it was a thin crust over bubbling lava.

Now, she was something else.

“Are you going elf on us?” he asked. Old elves faded, but not like this – and Jan wasn’t an elf.

She ignored his questions. “Are you hungry? I don’t eat any more.”

“I could eat.”

He noticed a bowl just inside the entrance to the hut. Steam rose from it, carrying a smell that was instantly familiar. His mother had made stews just like this. He picked it up and took a spoonful.

“Is this real?”

“It’s nourishing,” said Jan.

He grunted at that non-answer, but he still ate. His instinct was to never turn down the offer of a meal.

“I left Necrad because I was losing myself,” Jan said. “My faith, my hope. Call it what you will. I couldn’t stay there any longer. Despite everything we did, there’s a pall of darkness over that city. I went away looking for renewal. I went to the temples and looked for the Intercessors, but they didn’t answer. In the end I found my way back here. Back to where it all began for us.” She waved her hand at the ruins of the temple, and Alf couldn’t help notice that her fingers trailed off into mist when she moved. “The Illuminated One and his monks were dead, of course, and Acraist destroyed their library, but I was able to reconstruct some of their secrets. I only intended to stay here for a little while, but…” She shrugged. “That’s not how things turned out.”

“You dead?”

She laughed. “You haven’t changed, Alf. Always cutting things down to the simplest possible question. No, I’m not dead. I’m on a different path now, though. I’m the new Illuminated One, I suppose. I commune with the light.” She brushed back her greying hair. She still had little silver bells and talismans woven into it, but they made no sound.

“Right, right. Sounds nice.” He stirred his stew, trying to work out what it meant for Jan to call herself the Illuminated One. Back home, the village clerics always warned their flocks to shun the followers of the Illuminated. It was misguided, they preached, to reject the kindly hand of the holy Intercessors. Mortals were not meant to commune with cosmic forces directly. The weaving of fate was supposed to be beyond mortal comprehension. Clerics prayed to the Intercessors, and the Intercessors passed word to whatever was up there.

Alf’s grasp of theology was on a par with his history.

“You’re thinking that I sound like the crazy monks who used to beg for alms at harvest time, back when you were a boy,” said Jan, a mischievous smile playing around her faint lips.

“I don’t like it when people read my thoughts,” snapped Alf.

Jan flickered, her whole form vanishing for an eye blink. “I didn’t,” she said, “I wouldn’t do that. I don’t need to, Alf – I know your face. I can tell when you have doubts.”

“Aye, well. I have thoughts so rarely, I want to keep ’em for myself.”

“And your thought was a true one. Those monks were among the last acolytes of the Illuminated One. They were guardians of an ancient tradition, humanity’s first path towards the light. The Wood Elves taught us another way, through the Intercessors. I once followed the elven way, but I’m on the older path now.”

“You don’t believe in the Intercessors any more?” Alf had never been especially devout, but reverence for the Intercessors was deeply ingrained into him. He’d always liked the thought that even when things seemed darkest, wiser powers were watching over everyone.

“Oh, the spirits are real. But they don’t talk to me any more. I lost the blessing before we got to Necrad. I hoped that they’d come back after we defeated Lord Bone, but they didn’t.” She smiled. “Nothing turned out quite like we hoped, did it?”

“I didn’t know.” He stopped eating. “You helped us pray, though. Said the litanies and all. Took Peir’s confession.” In truth, Alf had never found much of worth in the prayers. It had all seemed like a waste of time to him. He could always think of something more productive to do than sit around and listen to the litany. But he’d sat there and listened, for Peir’s sake if nothing else, and it had been a comfort.

“I was still your cleric. Even if my own beliefs wavered, I could still say the words if they helped you. Faith is a strange thing, Alf. If you hold true to something, if you hold onto it with all your strength, body and soul – you can accomplish wonders. Peir did. He never stopped believing, not even when everything looked hopeless. And he brought us through.” A sad smile ghosted across her face. “My own doubts didn’t matter a bit, compared to his certainty. It was what we needed then. Now… now it’s up to us that are left. Or, well, to you.”

“You’re not coming back to Necrad.”

“I cannot.” The light in her flickered for a moment at the thought of returning to Lord Bone’s city. “Tell me, where were you when I called? My dream-sendings could not enter Necrad, so I know you weren’t there when you got my message. Why did you leave the city?”

Why indeed? “I got hurt,” he said slowly, “down in the Pits. A linnorm poisoned me. Healers patched me up, of course, but…” He shoved the spoon around the bowl, as though the answer was hidden in stew that was probably an illusion or a parable anyway. “But I knew I’d messed up. I let my guard down. I needed to get my nerve back, so I went for a walk.” He shifted awkwardly and looked down at his feet. “Been walking for a few years.”

“You were badly wounded,” said Jan, her voice full of concern.

“I’ve had worse,” Alf lied. Or half lied. He’d suffered worse injuries, certainly, during the war. But back then, he was never alone. If he fell, then Thurn or Gundan or Peir would step in to hold the line, Jan or Blaise or Lath would treat his wounds. But he had been alone when he faced the linnorm, alone as he crawled back up through the endless Pits. Nearly alone when he died.

“Where did you go?”

“North, first. Through the New Provinces. They’ve grown like you wouldn’t believe – they’re building forts all along the edge of the wood, and clearing farmland. Great bloody crowds of people coming up through Necrad, now, seeking their fortune on the frontier. Dwarves, too. They found hills full of gold. I went looking for Thurn, first, but I couldn’t find him. The Wilder have gone into the deep wood.” He’d searched for the tribes in primordial wilderness, tangled and unwelcoming. He’d wandered there and in the wastes for months, and scarcely seen another living mortal. The Wilder had avoided him deliberately. The sword he bore was a horror to them: a weapon forged by Witch Elves.

Thurn always reminded them that the Witch Elves conquered the Wilder long before they’d attacked the rest of the world.

“I was looking for… I don’t know. Trouble. Evil. I went searching through all the old Witch Elf strongholds I could find, looking for any of Bone’s allies that got away. I went hunting a dragon I’d heard tell of in the New Provinces. All for nought.”

Alf closed his eyes. His heart was pounding as if he was in the middle of a battle, even though he knew there was nothing to fear. There were few safer places in the world than this valley.

“Then back south through the Dwarfholt and the Cleft. I thought I’d go home. Didn’t even make it as far as Highfield before…” He shook his head. “No one remembered me. They knew the Lammergeier, of course, so I got to sit at the right hand of all the lords and sleep in beds with silken sheets, everyone licking my arse and telling me things that don’t matter about court nonsense. But no one knew me. And why would they? Haven’t been back since I went away adventuring. Most kids who run off end up dead in some goblin-hole within

“An ogre,” proclaimed the old man from the corner by the hearth, “a fearsome ogre! Iron-toothed, yellow-eyed, arms like oak branches!” He wobbled as he crossed the room towards the table of adventurers. “I saw it not three days ago, up on the High Moor. The beast must be slain, lest it find its way down to our fields and flocks!”

One of the young lads was beefy and broad-shouldered, Mulladale stock. He fancied himself a fighter, with that League-forged sword and patchwork armour. “I’ll wager it’s one of Lord Bone’s minions, left over from the war,” he declared loudly. “We’ll hunt it down!”

“I can track it!” This was a woman in green, her face tattooed. A Wilder-woman of the northern woods – or dressed as one, anyway. “We just need to find its trail.”

“There are places of power up on the High Moor,” said a third, face shadowed by his hood. He spoke with the refined tones of a Crownland scholar. An apprentice mage, cloak marked with the sign of the Lord who’d sponsored him. He probably had a star-trap strung outside in the bushes. “Ancient temples, shrines to forgotten spirits. Such an eldritch beast might…”

He paused, portentously. Alf bloody hated it when wizards did that, leaving pauses like pit traps in the conversation. Just get on with it, for pity’s sake.

Life was too short.

“… be drawn to such places. As might other… legacies of Lord Bone.”

“We’ll slay it,” roared the Mulladale lad, “and deliver this village from peril!”

That won a round of applause from the locals, more for the boy’s enthusiasm than any prospect of success. The adventurers huddled over the table, talking ogre-lore, talking about the dangers of the High Moor and the virtues of leaving at first light.

Alf scowled, irritated but unable to say why. He’d finish his drink, he decided, and then turn in. Maybe he’d be drunk enough to fall straight asleep. The loon had disturbed a rare evening of forgetfulness. He’d enjoyed sitting there, listening to village gossip and tall tales and the crackling of the fire. Now, the spell was broken and he had to think about monsters again.

He’d been thinking about monsters for a long time.

The old man sat down next to Alf. Apparently, he wasn’t done. He wasn’t that old, either – Alf realised he was about the same age. They’d both seen the wrong side of forty-five winters. “Ten feet tall it was,” he exclaimed, sending spittle flying into Alf’s tankard, “and big tusks, like a bull’s horns, at the side of its mouth.” He stuck his fingers out to illustrate. “It had the stink of Necrad about it. They have the right of it – it’s one of Bone’s creatures that escaped! The Nine should have put them all to the sword!”

“Bone’s ogres,” said Alf, “didn’t have tusks.” His voice was croaky from disuse. “They cut ’em off. Your ogre didn’t come out of Necrad.”

“You didn’t see the beast! I did! Only the Pits of Necrad could spawn such—”

“You haven’t seen the sodding Pits, either,” said Alf. He felt the cold rush of anger, and stood up. He needed to be away from people. He stumbled across the room towards the stairs.

Another of the locals caught his arm. “Bit of luck for you, eh?” The fool was grinning and red-cheeked. Twist, break the wrist. Grab his neck, slam his face into the table. Kick him into the two behind him. Then grab a weapon. Alf fought against his honed instincts. The evening’s drinking had not dulled his edge enough.

He dug up words. “What do you mean?”

“You said you were going off up the High Moor tomorrow. You’d run straight into that ogre’s mouth. Best you stay here another few days, ’til it’s safe.”

“Safe,” echoed Alf. He pulled his arm free. “I can’t stay. I have to go and see an old friend.”

The inn’s only private room was upstairs. Sleeping in the common room was a copper a night, the private room an exorbitant six for a poky attic room and the pleasure of hearing the innkeeper snore next door.

Alf locked the door and took Spellbreaker from its hiding place under the bed. The sword slithered in his grasp, metal twisting beneath the dragonhide.

“I could hear them singing about you.” Its voice was a leaden whisper. “About the siege of Necrad.”

“Just a drinking song,” said Alf, “nothing more. They didn’t know it was me.”

“They spoke the name of my true wielder, and woke me from dreams of slaughter.”

“It rhymes with rat-arsed, that’s all.”

“No, it doesn’t.”

“It does the way they say it. Acra-sed.”

“It’s pronounced with a hard ‘t’,” said the sword. “Acrai-st the Wraith-Captain, Hand of Bone.”

“Well,” said Alf, “I killed him, so I get to say how it’s said. And it’s rat-arsed. And so am I.”

He shoved the sword back under the bed, then threw himself down, hoping to fall into oblivion. But the same dream caught him again, as it had for a month, and it called him up onto the High Moor to see his friend.

The adventurers left at first light.

Alf left an hour later, after a leisurely breakfast. Getting soft, he muttered to himself, but he still caught up with them at the foot of a steep cliff, arguing over which of the goat paths would bring them up onto the windy plateau of the High Moor. Alf marched past them, shoulders hunched against the cold of autumn.

“Hey! Old man!” called one of them. “There’s a troll out there!”

Alf grunted as he studied the cliff ahead. It was steep, but not insurmountable. Berys and he had scaled the Wailing Tower in the middle of a howling necrostorm. This was nothing. He found a handhold and hauled himself up the rock face, ignoring the cries of the adventurers below. The Wilder girl followed him a little way, but gave up as Alf rapidly outdistanced her.

His shoulders, his knees ached as he climbed. Old fool. Showing off for what? To impress some village children? Why not wave Spellbreaker around? Or carry Lord Bone’s skull around on a pole? If you want glory, you’re twenty years too late, he thought to himself. He climbed on, stretching muscles grown stiff from disuse.

At the top, he sat down on a rock to catch his breath. He’d winded himself. The Wailing Tower, too, was nearly twenty years ago.

He pulled his cloak around himself to ward off the breeze, and lingered there for a few minutes. He watched the adventurers as they debated which path to take, and eventually decided on the wrong one, circling south-east along the cliffs until they vanished into the broken landscape below the moor. He looked out west, across the Mulladales, a patchwork of low hills and farmlands and wooded coppices. Little villages, little lives. All safe.

Twenty years ago? Twenty-one? Whenever it was, Lord Bone’s armies came down those goat paths. Undead warriors scuttling down the cliffs head first like bony lizards. Wilder scouts with faces painted pale as death. Witch Elf knights mounted on winged dreadworms. Golems, furnaces blazing with balefire. Between all those horrors and the Mulladales stood just nine heroes.

“It was twenty-two years ago,” said Spellbreaker. The damn sword was listening to his thoughts again – or had he spoken out loud? “Twenty-two years since I ate the soul of the Illuminated.”

“We beat you bastards good,” said Alf. “And chased you out of the temple. Peir nearly slew Acraist then, do you remember?”

“Vividly,” replied the sword.

Peir, his hammer blazing with the fire of the Intercessors. Berys, flinging vials of holy water she’d filched from the temple. Gundan, bellowing a war cry as he swung Chopper. Gods, they were so young then. Children, really, only a few years older than the idiot ogre-hunters. The battle of the temple was where they’d first proved themselves heroes. The start of a long, bitter war against Lord Bone. Oh, they’d got side-tracked – there’d been prophecies and quests and strife aplenty to lead them astray – but the path to Necrad began right here, on the edge of the High Moor.

He imagined his younger self struggling up those cliffs, that cheap pig-sticker of a sword clenched in his teeth. What would he have done, if that young warrior reached to the top and saw his future sitting there? Old, tired, tough as old boots. Still had all his limbs, but plenty of scars.

“We won,” he whispered to the shade of the past, “and it’s still bloody hard.”

“You,” said the sword, “are going crazy. You should get back to Necrad, where you belong.”

“When I’m ready.”

“I can call a dreadworm. Even here.”

“No.”

“Anything could be happening there. We’ve been away for more than two years, moping.” There was an unusual edge to the sword’s plea. Alf reached down and pulled Spellbreaker from its scabbard, so he could look the blade in the gemstone eye on its hilt and—

—Reflected in the polished black steel as it crept up behind him. Grey hide, hairy, iron-tusked maw drooling. Ogre.

Alf threw himself forward as the monster lunged at him and rolled to the edge of the cliff. Pebbles and dirt tumbled down the precipice, but he caught himself before he followed them over. He hoisted Spellbreaker, but the sword suddenly became impossibly heavy and threatened to tug him backwards over the cliff.

One of the bastard blade’s infrequent bouts of treachery. Fine.

He flung the heavy sword at the onrushing ogre, and the monster stumbled over it. Its ropy arms reached for him, but Alf dodged along the cliff edge, seized the monster’s wrist and pulled with all his might. The ogre, abruptly aware of the danger that they’d both fall to their deaths, scrambled away from the edge. It was off balance, and vulnerable. Alf leapt on the monster’s back and drove one elbow into its ear. The ogre bellowed in pain and fell forward onto the rock he’d been sitting on. Blood gushed from its nose, and the sight sparked unexpected joy in Alf. For a moment, he felt young again, and full of purpose. This, this was what he was meant for!

The ogre tried to dislodge him, but Alf wrapped his legs around its chest, digging his knees into its armpits, his hands clutching shanks of the monster’s hair. He bellowed into the ogre’s ear in the creature’s own language.

“Do you know who I am? I’m the man who killed the Chieftain of the Marrow-Eaters!”

The ogre clawed at him, ripping at his cloak. Its claws scrabbled against the dwarven mail Alf wore beneath his shirt. Alf got his arm locked across the ogre’s throat and squeezed.

“I killed Acraist the Wraith-Captain!”

The ogre reared up and threw itself back, crushing Alf against the rock. The impact knocked the air from his lungs, and he felt one of his ribs crack, but he held firm – and sank his teeth into his foe’s ear. He bit off a healthy chunk, spat it out and hissed:

“I killed Lord Bone.”

It was probably the pain of losing an earlobe, and not his threat, that made the ogre yield, but yield it did. The monster fell to the ground, whimpering.

Alf released his grip on the ogre’s neck and picked up Spellbreaker. Oh, now the magic sword was perfectly light and balanced in his hand. One swing, and the ogre’s head would go rolling across the ground. One cut, and the monster would be slain.

He slapped the ogre with the flat of the blade.

“Look at me.”

Yellow terror-filled eyes stared at him.

“There are adventurers hunting for you. They went south-east. You, run north. That way.” He pointed with the blade, unsure if the ogre even spoke this dialect. It was the tongue he’d learned in Necrad, the language the Witch Elves used to order their war-beasts around. “Run north!” he added in common, and he shoved the ogre again. The brute got the message and ran, loping on all fours away from Alf. It glanced back in confusion, unsure of what had just happened.

Alf lifted Spellbreaker, glared into the sword’s eye.

“I was testing you,” said the sword. “You haven’t had a proper fight in months. Tournies don’t count – no opponent has the courage to truly test you, and it’s all for show anyway. Your strength dwindles. My wielder must—”

“I’m not your bloody wielder. I’m your gaoler.”

“I am bored, wielder. Two years of wandering the forests and backroads. Two years of hiding and lurking. And when you finally pluck up the courage to go anywhere, it’s to an even duller village. I tell you, those people should have welcomed the slaughter my master brought, to relieve them of the tedium of their pathetic—”

“Try that again, and I’ll throw you off a cliff.”

“Do it. Someone will find me. Something. I’m a weapon of darkness, and I call to—”

“I’ll drop you,” said Alf wearily, “into a volcano.”

Last time, they’d reached the temple in two days. He’d spent twice as long already, trudging over stony ground, pushing through thorns and bracken, clambering around desolate tors and outcrops of bare rock. He’d known that finding the hidden ravine of the temple would be tricky, but it took him longer than he’d expected to reach Giant’s Rock, and that was at least a day’s travel from the ravine.

That big pillar of stone, one side covered with shaggy grey-green moss – that was Giant’s Rock, right? In his memory it was bigger. Alf squinted at the rock, trying to imagine how it might be mistaken for a hunched giant. He’d seen real giants, and they were a lot bigger.

If this was Giant’s Rock, he should turn south there to reach the valley. If it wasn’t, then turning south would bring him into the empty lands of the fells where no one lived.

Maybe they’d come from a more northerly direction, last time. He walked around the pillar of stone. It remained obstinately un-giant-like. No one ever accused Alf of having the soul of a poet. A rock pile was a rock pile to him. The empty sky above him, the empty land all around. He regretted letting that ogre run off; maybe he should have forced it to guide him to the valley. Turn south, or continue east?

The valley was well hidden. There’d been wars fought in these parts, hundreds of years ago, in the dark days after… after… after some kingdom had fallen. The Old Kingdom. Alf’s grasp of history was as good as could be expected of a Mulladale farm boy who’d could barely write his name, and nearly thirty years of adventuring hadn’t taught him much more. Oh, he could tell you the best way to fight an animated skeleton, or loot an ancient tomb, but “whence came the skeleton” or “who built the tomb” were matters for cleverer heads. He remembered Blaise lecturing him on this battlefield, the wizard wasting his breath on talking when he should have been keeping it for walking. Different factions in the Old Kingdom clashed here. Rival cults, Blaise told him, fighting until both sides were exhausted and the Illuminated were driven into hiding. The green grass swallowed up the battlefields and the barrow tombs, and everything was forgotten until Lord Bone had called up those long-dead warriors. Skeletons crawled out of the dirt and took up their rusty swords, and roamed the High Moors again.

Last time, Thurn the Wilder led them. He could track anything and anyone, even the dead. He’d brought them straight to the secret path, following Lord Bone’s forces into the hidden heart of the temple. All Alf had to do was fight off the flying dreadworms sent to slow them down. Even then, Acraist had seen that the Nine of them were dangerous.

“No, he didn’t,” said the sword. It was the first time it had spoken since the cliff top.

“Stop that.”

“If Acraist thought you were a threat, he’d have sent more than a few riderless worms. He was intent on breaking the aegis of the temple, not worrying about you bandits. You were an irrelevant nuisance. You got lucky.”

“Well, he got killed. And so did Lord Bone, and you can’t say that was luck.”

A quiver ran through the sword. The blade’s equivalent of a derisive snort.

He took another step east, and the sword quivered again.

“What is it?”

“Nothing, O Lammergeier,” said Spellbreaker sullenly. Alf hated that nickname, given to him in the songs by some stupid poet drunk on metaphor. He’d never even seen one of the ugly vultures of the mountains beyond Westermarch. They were bone-breaking birds, feasters on marrow. And while Alf might be old and ugly enough now to resemble a vulture, the bloody song had given him that name twenty or so years ago. He’d broken Bone, hence – Sir Lammergeier.

Poetry was almost as bad as prophecy.

The sword only used the name when it wanted to annoy him – or distract him. What had that pretentious apprentice said in the inn, about creatures of Lord Bone sensing places of power? Alf drew the sword again and took a step forward. The jewelled eye seemed to wince, eldritch light flaring deep within the ruby.

He shook Spellbreaker. “Can you detect the temple?”

“No.”

Another step. Another wince.

“You bloody well can,” said Alf.

“It’s sanctified,” admitted Spellbreaker reluctantly. “Acraist protected me from the radiance, last time.”

Alf looked around at the moorland. No radiance was visible, at least none he had eyes to see.

“Well then.” He set off east, and only turned south when prompted by the twisting of the demonic sword.

Another day, and the terrain became familiar. Some blessing in the temple softened the harshness of the moor. Wildflowers grew all around. Streams cascaded down the rocks, chiming like silver bells. Alf felt weariness fall from his bones, sloughing away like he’d sunk into a warm bath.

Spellbreaker shrieked and rattled in its scabbard.

“It’s too bright. I cannot go in there. It will shatter me.”

“I’m not leaving you here.”

“Wielder, I cannot…”

Alf hesitated. Spellbreaker was among the most dangerous things to come out of Necrad, a weapon of surpassing evil. It could shatter any spell, break any ward. In the hands of a monster, it could wreak terrible harm upon the world. Even that ogre could become something dangerous under the blade’s tutelage. But maybe the sword was right – dragging it into the holy place might damage it. When they’d fought Acraist that first time, down in the valley, the Wraith-Captain wasn’t half as tough as when they battled him seven years later. The valley burned things of darkness.

Would it burn Alf if he carried the sword down there?

“Look,” sneered Spellbreaker. “You’re expected.”

A tiny candle flame of light danced in the air ahead of Alf. And then another kindled, and another, and another, a trail of sparks leading down into the valley.

Alf drew the sword and drove it deep into the earth. “Stay,” he said to it, scolding it like a dog.

Then down, into the hidden valley of the Illuminated One.

Rubble lay strewn across the valley. Acraist had shattered the temple arch before they’d arrived. Alf remembered the headlong race down the path, hastening to intervene before the Wraith-Captain slew the Illuminated One. Laerlyn leaping gracefully down the rocks, loosing arrows as she ran. Jan weeping even as she called on the Intercessors to shield them from Acraist’s death-spells. Miracles warring with dark magic in the air.

In retrospect, the greatest miracle was that none of them had tripped and broken their necks as they ran down the steep path into the valley. The little sparkling lights led Alf along the safest route, until he reached the valley floor. Then they shot off ahead of him, meteors racing over the rubble, dodging in and out of hiding places. There was something playful about their movements.

The Sanctum of the Illuminated One – another thing wizards did was Audibly Pronounce Capital Letters – was carved out of the rock of the canyon. Pillars covered with twining glyphs bore images of godly figures Alf didn’t recognise. One was a woman, her face so worn nothing of her features remained, although Alf could still make out chains carved on her wrists. Opposite her was a horned figure holding a staff, arcane sigils in an arc above him. He remembered Jan and Blaise had yammered about how bloody old the temple was – older than any shrine in Summerswell, even the big one in Arshoth.

If they liked old stuff, they’d love Alf now. Forty-five summers by the reckoning of the south, but Necrad didn’t have proper summers, or proper time, so who knew how old he was. He felt as ancient as the toppled statues around him.

He followed the lights, and they led him towards a hut of piled stones.

Jan sat waiting at the entrance.

She’d become thin – so thin he could see the hut through her, as though she was made of coloured glass. The little lights ran to her, flowed into her, and he could see them now like stars through the window of her body. She smiled at him, and it was like looking at a radiant sunset. Still, he shivered at the sight. They’d all changed so much.

The rest of the Nine had, anyway. Alf remained Alf.

“Hello, Aelfric,” said Jan.

“I got the dream you sent.”

She nodded. “And it guided you here.”

“Guided ain’t the way I’d put it, but aye.” He paused, awkwardly. He’d loved Jan, they all did, the little mouse of the Nine, but he’d never claimed to understand her. “Should I kneel?”

“Just sit, Alf. Holiness isn’t in your knees.”

Alf settled awkwardly opposite Jan. He found himself holding his breath, as if exhaling too forcefully might blow away the gossamer of her existence. “Jan… what happened to you?” Last time he’d seen her was when she left Necrad a decade ago. Then, she’d been exhausted by her work in the city. Angry, too – simmering, bitter, her kindness worn down until it was a thin crust over bubbling lava.

Now, she was something else.

“Are you going elf on us?” he asked. Old elves faded, but not like this – and Jan wasn’t an elf.

She ignored his questions. “Are you hungry? I don’t eat any more.”

“I could eat.”

He noticed a bowl just inside the entrance to the hut. Steam rose from it, carrying a smell that was instantly familiar. His mother had made stews just like this. He picked it up and took a spoonful.

“Is this real?”

“It’s nourishing,” said Jan.

He grunted at that non-answer, but he still ate. His instinct was to never turn down the offer of a meal.

“I left Necrad because I was losing myself,” Jan said. “My faith, my hope. Call it what you will. I couldn’t stay there any longer. Despite everything we did, there’s a pall of darkness over that city. I went away looking for renewal. I went to the temples and looked for the Intercessors, but they didn’t answer. In the end I found my way back here. Back to where it all began for us.” She waved her hand at the ruins of the temple, and Alf couldn’t help notice that her fingers trailed off into mist when she moved. “The Illuminated One and his monks were dead, of course, and Acraist destroyed their library, but I was able to reconstruct some of their secrets. I only intended to stay here for a little while, but…” She shrugged. “That’s not how things turned out.”

“You dead?”

She laughed. “You haven’t changed, Alf. Always cutting things down to the simplest possible question. No, I’m not dead. I’m on a different path now, though. I’m the new Illuminated One, I suppose. I commune with the light.” She brushed back her greying hair. She still had little silver bells and talismans woven into it, but they made no sound.

“Right, right. Sounds nice.” He stirred his stew, trying to work out what it meant for Jan to call herself the Illuminated One. Back home, the village clerics always warned their flocks to shun the followers of the Illuminated. It was misguided, they preached, to reject the kindly hand of the holy Intercessors. Mortals were not meant to commune with cosmic forces directly. The weaving of fate was supposed to be beyond mortal comprehension. Clerics prayed to the Intercessors, and the Intercessors passed word to whatever was up there.

Alf’s grasp of theology was on a par with his history.

“You’re thinking that I sound like the crazy monks who used to beg for alms at harvest time, back when you were a boy,” said Jan, a mischievous smile playing around her faint lips.

“I don’t like it when people read my thoughts,” snapped Alf.

Jan flickered, her whole form vanishing for an eye blink. “I didn’t,” she said, “I wouldn’t do that. I don’t need to, Alf – I know your face. I can tell when you have doubts.”

“Aye, well. I have thoughts so rarely, I want to keep ’em for myself.”

“And your thought was a true one. Those monks were among the last acolytes of the Illuminated One. They were guardians of an ancient tradition, humanity’s first path towards the light. The Wood Elves taught us another way, through the Intercessors. I once followed the elven way, but I’m on the older path now.”

“You don’t believe in the Intercessors any more?” Alf had never been especially devout, but reverence for the Intercessors was deeply ingrained into him. He’d always liked the thought that even when things seemed darkest, wiser powers were watching over everyone.

“Oh, the spirits are real. But they don’t talk to me any more. I lost the blessing before we got to Necrad. I hoped that they’d come back after we defeated Lord Bone, but they didn’t.” She smiled. “Nothing turned out quite like we hoped, did it?”

“I didn’t know.” He stopped eating. “You helped us pray, though. Said the litanies and all. Took Peir’s confession.” In truth, Alf had never found much of worth in the prayers. It had all seemed like a waste of time to him. He could always think of something more productive to do than sit around and listen to the litany. But he’d sat there and listened, for Peir’s sake if nothing else, and it had been a comfort.

“I was still your cleric. Even if my own beliefs wavered, I could still say the words if they helped you. Faith is a strange thing, Alf. If you hold true to something, if you hold onto it with all your strength, body and soul – you can accomplish wonders. Peir did. He never stopped believing, not even when everything looked hopeless. And he brought us through.” A sad smile ghosted across her face. “My own doubts didn’t matter a bit, compared to his certainty. It was what we needed then. Now… now it’s up to us that are left. Or, well, to you.”

“You’re not coming back to Necrad.”

“I cannot.” The light in her flickered for a moment at the thought of returning to Lord Bone’s city. “Tell me, where were you when I called? My dream-sendings could not enter Necrad, so I know you weren’t there when you got my message. Why did you leave the city?”

Why indeed? “I got hurt,” he said slowly, “down in the Pits. A linnorm poisoned me. Healers patched me up, of course, but…” He shoved the spoon around the bowl, as though the answer was hidden in stew that was probably an illusion or a parable anyway. “But I knew I’d messed up. I let my guard down. I needed to get my nerve back, so I went for a walk.” He shifted awkwardly and looked down at his feet. “Been walking for a few years.”

“You were badly wounded,” said Jan, her voice full of concern.

“I’ve had worse,” Alf lied. Or half lied. He’d suffered worse injuries, certainly, during the war. But back then, he was never alone. If he fell, then Thurn or Gundan or Peir would step in to hold the line, Jan or Blaise or Lath would treat his wounds. But he had been alone when he faced the linnorm, alone as he crawled back up through the endless Pits. Nearly alone when he died.

“Where did you go?”

“North, first. Through the New Provinces. They’ve grown like you wouldn’t believe – they’re building forts all along the edge of the wood, and clearing farmland. Great bloody crowds of people coming up through Necrad, now, seeking their fortune on the frontier. Dwarves, too. They found hills full of gold. I went looking for Thurn, first, but I couldn’t find him. The Wilder have gone into the deep wood.” He’d searched for the tribes in primordial wilderness, tangled and unwelcoming. He’d wandered there and in the wastes for months, and scarcely seen another living mortal. The Wilder had avoided him deliberately. The sword he bore was a horror to them: a weapon forged by Witch Elves.

Thurn always reminded them that the Witch Elves conquered the Wilder long before they’d attacked the rest of the world.

“I was looking for… I don’t know. Trouble. Evil. I went searching through all the old Witch Elf strongholds I could find, looking for any of Bone’s allies that got away. I went hunting a dragon I’d heard tell of in the New Provinces. All for nought.”

Alf closed his eyes. His heart was pounding as if he was in the middle of a battle, even though he knew there was nothing to fear. There were few safer places in the world than this valley.

“Then back south through the Dwarfholt and the Cleft. I thought I’d go home. Didn’t even make it as far as Highfield before…” He shook his head. “No one remembered me. They knew the Lammergeier, of course, so I got to sit at the right hand of all the lords and sleep in beds with silken sheets, everyone licking my arse and telling me things that don’t matter about court nonsense. But no one knew me. And why would they? Haven’t been back since I went away adventuring. Most kids who run off end up dead in some goblin-hole within

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved