- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

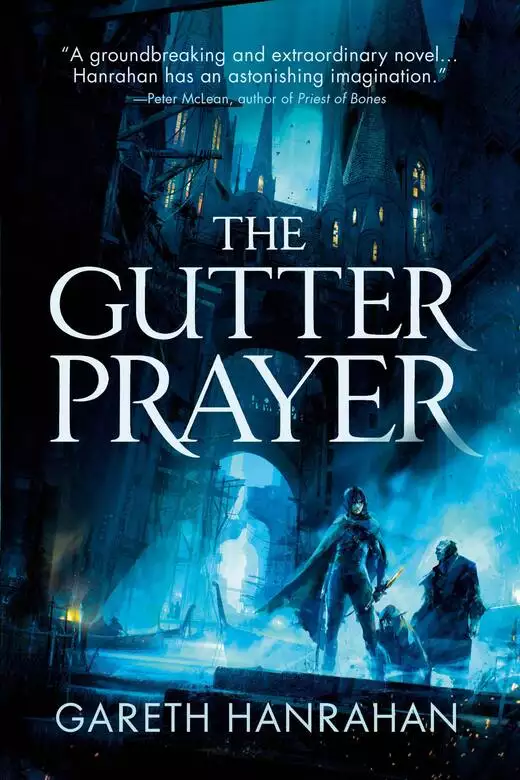

In the ancient city of Guerdon, three thieves — an orphan, a ghoul and a cursed man — are accused of a crime they didn't commit. Their quest for revenge exposes a perilous conspiracy, the seeds of which were sown long before they were born.

A centuries-old magical war is on the verge of reigniting, and in the tunnels deep below the city, a malevolent power stirs. Only by standing together can the three friends prevent a conflict that would bring total devastation to their city — and the world beyond.

Set in a world of dark gods and dangerous magic, The Gutter Prayer is thrilling and visceral debut fantasy from an exciting new talent.

Release date: January 22, 2019

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 560

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Gutter Prayer

Gareth Hanrahan

Some will come not as travellers, but as refugees. You stand as testament to the freedom that Guerdon offers: freedom to worship, freedom from tyranny and hatred. Oh, this freedom is conditional, uncertain—the city has, in its time, chosen tyrants and fanatics and monsters to rule it, and you have been part of that, too—but the sheer weight of the city, its history and its myriad peoples always ensure that it slouches back eventually into comfortable corruption, where anything is permissible if you’ve got money.

Some will come as conquerors, drawn by that wealth. You were born in such a conflict, the spoils of a victory. Sometimes, the conquerors stay and are slowly absorbed into the city’s culture. Sometimes, they raze what they can and move on, and Guerdon grows again from the ashes and rubble, incorporating the scar tissue into the living city.

You are aware of all this, as well as certain other things, but you cannot articulate how. You know, for example, that two Tallowmen guards patrol your western side, moving with the unearthly speed and grace of their kind. The dancing flames inside their heads illuminate a row of carvings on your flank, faces of long-dead judges and politicians immortalised in stone while their mortal remains have long since gone down the corpse shafts. The Tallowmen jitter by, and turn right down Mercy Street, passing the arch of your front door beneath the bell tower.

You are aware, too, of another patrol coming up behind you.

And in that gap, in the shadows, three thieves creep up on you. The first darts out of the mouth of an alleyway and scales your outer wall. Ragged hands find purchase in the cracks of your crumbling western side with inhuman quickness. He scampers across the low roof, hiding behind gargoyles and statues when the second group of Tallowmen pass by. Even if they’d looked up with their flickering fiery eyes, they’d have seen nothing amiss.

Something in the flames of the Tallowmen should disquiet you, but you are incapable of that or any other emotion.

The ghoul boy comes to a small door, used only by workmen cleaning the lead tiles of the roof. You know—again, you don’t know how you know—that this door is unlocked, that the guard who should have locked it was bribed to neglect that part of his duties tonight. The ghoul boy tries the door, and it opens silently. Yellow-brown teeth gleam in the moonlight.

Back to the edge of the roof. He checks for the tell-tale light of the Tallowmen on the street, then drops a rope down. Another thief emerges from the same alleyway and climbs. The ghoul hauls up the rope, grabs her hand and pulls her out of sight in the brief gap between patrols. As she touches your walls, you know her to be a stranger to the city, a nomad girl, a runaway. You have not seen her before, but a flash of anger runs through you at her touch as you share, impossibly, in her emotion.

You have never felt this or anything else before, and wonder at it. Her hatred is not directed at you, but at the man who compels her to be here tonight, but you still marvel at it as the feeling travels the length of your roof-ridge.

The girl is familiar. The girl is important.

You hear her heart beating, her shallow, nervous breathing, feel the weight of the dagger in its sheathe pressing against her leg. There is, however, something missing about her. Something incomplete.

She and the ghoul boy vanish in through the open door, hurrying through your corridors and rows of offices, then down the side stairs back to ground level. There are more guards inside, humans—but they’re stationed at the vaults on the north side, beneath your grand tower, not here in this hive of paper and records; the two thieves remain unseen as they descend. They come to one of your side doors, used by clerks and scribes during the day. It’s locked and bolted and barred, but the girl picks the lock even as the ghoul scrabbles at the bolts. Now the door’s unlocked, but they don’t open it yet. The girl presses her eye to the keyhole and watches, waits, until the Tallowmen pass by again. Her hand fumbles at her throat, as if looking for a necklace that usually rests there, but her neck is bare. She scowls, and the flash of anger at the theft thrills you.

You are aware of the ghoul, of his physical presence within you, but you feel the girl far more keenly, share her fretful excitement as she waits for the glow of the Tallowmen candles to diminish. This, she fears, is the most dangerous part of the whole business.

She’s wrong.

Again, the Tallowmen turn the corner onto Mercy Street. You want to reassure her that she is safe, that they are out of sight, but you cannot find your voice. No matter—she opens the door a crack and gestures, and the third member of the trio lumbers from the alley.

Now, as he thuds across the street in the best approximation of a sprint he’s capable of, you see why they needed to open the ground-level door when they already had the roof entrance. The third member of the group is a Stone Man. You remember when the disease—or curse—first took root in the city. You remember the panic, the debates about internment, about quarantines. The alchemists found a treatment in time, and a full-scale epidemic was forestalled. But there are still outbreaks, patches, leper colonies of sufferers in the city. If the symptoms aren’t caught early enough, the result is the motley creature that even now lurches over your threshold—a man whose flesh and bone are slowly transmuting into rock. Those afflicted by the plague grow immensely strong, but every little bit of wear and tear, every injury hastens their calcification. The internal organs are the last to go, so towards the end they are living statues, unable to move or see, locked forever in place, labouring to breathe, kept alive only by the charity of others.

This Stone Man is not yet paralysed, though he moves awkwardly, dragging his right leg. The girl winces at the noise as she shuts the door behind him, but you feel an equally unfamiliar thrill of joy and relief as her friend reaches the safety of their hiding place. The ghoul’s already moving, racing down the long silent corridor that’s usually thronged with prisoners and guards, witnesses and jurists, lawyers and liars. He runs on all fours, like a grey dog. The girl and the Stone Man follow; she stays low, but he’s not that flexible. Fortunately, the corridor does not look out directly onto the street outside, so, even if the patrolling Tallowmen glanced this way, they wouldn’t see him.

The thieves are looking for something. They check one record room, then another. These rooms are secure, locked away behind iron doors, but stone is stronger and the Stone Man bends or breaks them, one by one, enough for the ghoul or the human girl to wriggle through and search.

At one point, the girl grabs the Stone Man’s elbow to hasten him along. A native of the city would never do such a thing, not willingly, not unless they had the alchemist’s cure to hand. The curse is contagious.

They search another room, and another and another. There are hundreds of thousands of papers here, organised by a scheme that is a secret of the clerks, whispered only from one to another, passed on like an heirloom. If you knew what they sought, and they could understand your speech, you could perhaps tell them where to find what they seek, but they fumble on half blind.

They cannot find what they are looking for. Panic rises. The girl argues that they should leave, flee before they are discovered. The Stone Man shakes his head, as stubborn and immovable as, well, as stone. The ghoul keeps his own counsel, but hunches down, pulling his hood over his face as if trying to remove himself from their debate. They will keep looking. Maybe it’s in the next room.

Elsewhere inside you, one guard asks another if he heard that. Why, might that not be the sound of an intruder? The other guards look at each other curiously, but then in the distance, the Stone Man smashes down another door, and the now-attentive guards definitely hear it.

You know—you alone know—that the guard who alerted his fellows is the same one who left the rooftop door unlocked. The guards fan out, sound the alarm, begin to search the labyrinth within you. The three thieves split up, try to evade their pursuers. You see the chase from both sides, hunters and hunted.

And, after the guards leave their post by the vaults, other figures enter. Two, three, four, climbing up from below. How have you not sensed them before? How did they come upon you, enter you, unawares? They move with the confidence of experience, sure of every action. Veterans of their trade.

The guards find the damage wrought by the Stone Man and begin to search the south wing, but your attention is focused on the strangers in your vault. With the guards gone, they work unimpeded. They unwrap a package, press it against the vault door, light a fuse. It blazes brighter than any Tallowman’s candle, fizzing and roaring and then—

—you are burning, broken, rent asunder, thrown into disorder. Flames race through you, all those thousands of documents catching in an instant, old wooden floors fuelling the inferno. The stones crack. Your western hall collapses, the stone faces of judges plummeting into the street outside to smash on the cobblestones. You feel your awareness contract as the fire numbs you. Each part of you that is consumed is no longer part of you, just a burning ruin. It’s eating you up.

It is not that you can no longer see the thieves—the ghoul, the Stone Boy, the nomad girl who taught you briefly to hate. It is that you can no longer know them with certainty. They flicker in and out of your rapidly fragmenting consciousness as they move from one part of you to another.

When the girl runs across the central courtyard, pursued by a Tallowman, you feel every footstep, every panicked breath she takes as she runs, trying to outdistance creatures that move far faster than her merely human flesh can hope to achieve. She’s clever, though—she zigzags back into a burning section, vanishing from your perception. The Tallowman hesitates to follow her into the flames for fear of melting prematurely.

You’ve lost track of the ghoul, but the Stone Man is easy to spot. He stumbles into the High Court, knocking over the wooden seats where the Lords Justice and Wisdom sit when proceedings are in session. The velvet cushions of the viewer’s gallery are already on fire. More pursuers close in on him. He’s too slow to escape.

Around you, around what’s left of you, the alarm spreads. A blaze of this size must be contained. People flee the neighbouring buildings, or hurl buckets of water on roofs set alight by sparks from your inferno. Others gather to gawk, as if the destruction of one of the city’s greatest institutions was a sideshow for their amusement. Alchemy wagons race through the streets, carrying vats of fire-quelling liquids, better than water for dealing with a conflagration like this. They know the dangers of a fire in the city; there have been great fires in the past, though none in recent decades. Perhaps, with the alchemists’ concoctions and the discipline of the city watch, they can contain this fire.

But it is too late for you.

Too late, you hear the voices of your brothers and sisters cry out, shouting the alarm, rousing the city to the danger.

Too late, you realise what you are. Your consciousness shrinks down, takes refuge in its vessel. That is what you are, if not what you have always been.

You feel a second emotion—fear—as the flames climb the tower. Something beneath you breaks, and the tower sags suddenly to one side, sending you rocking back and forth. Your voice jangles in the tumult, a sonorous death rattle.

Your supports break, and you fall.

Carillon crouches in the shadow, eyes fixed on the door. Her knife is in her hand, a gesture of bravado to herself more than a deadly weapon. She’s fought before, cut people with it, but never killed with it. Cut and run, that’s her way.

In this crowded city, that’s not necessarily an option.

If one guard comes through the door, she’ll wait until he goes past her hiding place, then creep after him and cut his throat. She tries to envisage herself doing it, but can’t manage it. Maybe she can get away with just scaring him, or shanking him in the leg so he can’t chase them.

If it’s two, then she’ll wait until they’re about to find the others, hiss a warning and leap on one of them. Surely, between herself, Spar and Rat, they’ll be able to take out two guards without giving themselves away.

Surely.

If it’s three, same plan, only riskier.

She doesn’t let her mind dwell on the other possibility—that it won’t be humans like her who can be cut with her little knife, but something worse like the Tallowmen or Gullheads. The city has bred horrors all its own.

Every instinct in her tells her to run, to flee with her friends, to risk Heinreil’s wrath for returning empty-handed. Better yet, to not return at all, but take the Dowager Gate or the River Gate out of the city tonight, be a dozen miles away before dawn.

Six. The door opens and it’s six guards, all human, one two three big men, in padded leathers, maces in hand, and three more with pistols. She freezes for an instant in terror, unable to act, unable to run, caught against the cold stone of the old walls.

And then—she feels the shock through the wall before she hears the roar, the crash. She feels the whole House of Law shatter. She was in Severast when there was an earth tremor once, but it’s not like that—it’s more like a lightning strike and thunderclap right on top of her. She springs forward without thinking, as if the explosion had physically struck her, too, jumping through the scattered confusion of the guards.

One of them fires his pistol, point blank, so close she feels the sparks, the rush of air past her head, hot splinters of metal or stone showering down across her back, but the pain doesn’t blossom and she knows she’s not hit even as she runs.

Follow me, she prays as she runs blindly down the passageway, ducking into one random room and another, bouncing off locked doors. From the shouts behind her, she knows that some of them are after her. It’s like stealing fruit in the market—one of you makes a big show of running, distracts the fruitseller, and the others grab an apple each and one more for the runner. Only, if she gets caught, she won’t be let off with a thrashing. Still, she’s got a better chance of escaping than Spar has.

She runs up a short stairway and sees an orange glow beneath the door. Tallowmen, she thinks, imagining their blazing wicks on the far side, before she realises that the whole north wing of the square House is ablaze. The guards are close behind her, so she opens the door anyway, ducking low to avoid the thick black smoke that pours through.

She skirts along the edge of the burning room. It is a library, with long rows of shelves packed with rows of cloth-bound books, journals of civic institutions, proceedings of parliament. At least, half of it is a library; the other half was a library. Old books burn quickly. She clings to the wall, finding her way through the smoke by touch, trailing her right hand along the stone blocks while groping ahead with her left.

One of the guards has the courage to follow her in, but, from the sound of his shouts, she guesses he went straight forward, thinking she’d run towards the fires. There’s a creak, and a crash, and a shower of sparks as one of the burning bookcases topples. The guard’s shouts to his fellows become a scream of pain, but she can do nothing for him. She can’t see, can scarcely breathe. She fights down panic and keeps going until she comes to the side wall.

The House of Law is a quadrangle of buildings around a central green. They hang thieves there, and hanging seems like a better fate than burning right now. But there was a row of windows, wasn’t there? On the inside face of the building, looking out onto that green. She’s sure there is, there must be, because the fires have closed in behind her and there’s no turning back.

The outstretched fingers of her left hand touch warm stone. The side wall. She scrabbles and sweeps her fingers over it, looking for the windows. They’re higher than she remembers, and she can barely reach the sill even when stretching, standing on tiptoes. The windows are thick, leaded glass, and, while the fires have blown some of them out, this one is intact. She grabs a book off a shelf and flings it at the glass, to no avail. It bounces back. There’s nothing she can do to break the glass from down here.

On this side, the sill’s less than an inch wide, but if she can get up there, maybe she can lever one of the panes out, make an opening. She takes a step back to make a running jump up, and a hand closes around her ankle.

“Help me!”

It’s the guard who followed her in. The burning bookcase must have fallen on him. He’s crawling, dragging a limp and twisted leg, and he’s horribly burnt down his left side. Weeping white-red blisters and blackened flesh on his face.

“I can’t.”

He’s still clutching his pistol, and he tries to aim it at her while still grabbing her ankle, but she’s faster. She grabs his arm and lifts it, pulls the trigger for him. The report, that close to her ear, is deafening, but the shot smashes part of the window behind her. More panes and panels fall, leaving a gap in the stained glass large enough to crawl through if she can climb up to it.

A face appears in the gap. Yellow eyes, brown teeth, pitted flesh—a grin of wickedly sharp teeth. Rat extends his rag-wrapped hand through the window. Cari’s heart leaps. She’s going to live. In that moment, her friend’s monstrous, misshapen face seems as beautiful as the flawless features of a saint she once knew. She runs towards Rat—and stops.

Burning’s a terrible way to die. She’s never thought so before, but now that it’s a distinct possibility it seems worse than anything. Her head feels weird, and she knows she’s not thinking straight, but between the smoke and the heat and terror, weird seems wholly reasonable. She kneels down, slips an arm beneath the guard’s shoulders, helps him stand on his good leg, to limp towards Rat.

“What are you doing?” hisses the ghoul, but he doesn’t hesitate either. He grabs the guard by the shoulders when the wounded man is within reach of the window, and pulls him through the gap. Then he comes back for her, pulling her up, too. Rat’s sinewy limbs aren’t as tough or as strong as Spar’s stone-cursed muscles, but he’s more than strong enough to lift Carillon out of the burning building with one hand and pull her through into the blessed coolness of the open courtyard.

The guard moans and crawls away across the grass. They’ve done enough for him, Carillon decides; a half-act of mercy is all they can afford.

“Did you do this?” Rat asks in horror and wonder, flinching as part of the burning buildings collapses in on itself. The flames twine around the base of the huge bell tower that looms over the north side of the quadrangle.

Carillon shakes her head. “No, there was some sort of … boom. Where’s Spar?”

“This way.” Rat scurries off, and she runs after him. South, along the edge of the garden, past the empty old gibbets, away from the fire, towards the courts. There’s no way now to get what they came for, even if the documents that Heinreil wants still exist and aren’t falling around her as a blizzard of white ash, but maybe they can get away if they can get out onto the streets again. They just need to find Spar, find that big slow limping lump of rock, and get out.

She could leave him behind, just like Rat could abandon her. The ghoul could make it over the wall in a flash; ghouls are prodigious climbers. But they’re friends—the first true friends she’s had in a long time. Rat found her on the streets after she was stranded in this city, and he introduced her to Spar, who gave her a place to sleep safely.

The two also introduced her to Heinreil, but that wasn’t their fault—Guerdon’s underworld is dominated by the thieves’ brotherhood, just like its trade and industry is run by the guild cartels. If they’re caught, it’s Heinreil’s fault. Another reason to hate him.

There’s a side door ahead, and if she hasn’t been turned around it’ll open up near where they came in, and that’s where they’ll find Spar.

Before they can get to it, the door opens and out comes a Tallowman.

Blazing eyes in a pale, waxy face. He’s an old one, worn so thin he’s translucent in places, and the fire inside him shines through holes in his chest. He’s got a huge axe, bigger than Cari could lift, but he swings it easily with one hand. He laughs when he sees her and Rat outlined against the fire.

They turn and run, splitting up. Rat breaks left, scaling the wall of the burning library. She turns right, hoping to vanish into the darkness of the garden. Maybe she can hide behind a gibbet or some monument, she thinks, but the Tallowman’s faster than she can imagine. He flickers forward, a blur of motion, and he’s right in front of her. The axe swings, she throws herself down and to the side and it whistles right past her.

Again the laugh. He’s toying with her.

She finds her courage. Finds she hasn’t dropped her knife. She drives it right into the Tallowman’s soft waxy chest. His clothes and his flesh are the same substance, yielding and mushy as warm candle wax, and the blade goes in easily. He just laughs again, the wound closing almost as fast as it opened, and now her knife’s in his other hand. He reverses it, stabs it down, and her right shoulder’s suddenly black and slick with blood.

She doesn’t feel the pain yet, but she knows its coming.

She runs again, half stumbling towards the flames. The Tallowman hesitates, unwilling to follow, but it stalks her, herding her, cackling as it goes. It offers her a choice of deaths—run headlong into the fire and burn to death, bleed out here on the grass where so many other thieves met their fates, or turn back and let it dismember her with her own knife.

She wishes she had never come back to this city.

The heat from the blaze ahead of her scorches her face. The air’s so hot it hurts to breathe, and she knows the smell of soot and burning paper will never, ever leave her. The Tallowman keeps pace with her, flickering back and forth, always blocking her from making a break.

She runs towards the north-east corner. That part of the House of Law is on fire, too, but the flames seem less intense there. Maybe she can make it there without the Tallowman following her. Maybe she can even make it before it takes her head off with its axe. She runs, cradling her bleeding arm, bracing herself all the while for the axe to come chopping through her back.

The Tallowman laughs and comes up behind her.

And then there’s a clang, the ringing of a tremendous bell, and the sound lifts Carillon up, up out of herself, up out of the courtyard and the burning building. She flies high over the city, rising like a phoenix out of the wreckage. Behind her, below her, the bell tower topples down, and the Tallowman shrieks as burning rubble crushes it.

She sees Rat scrambling over rooftops, vanishing into the shadows across Mercy Street.

She sees Spar lumbering across the burning grass, towards the blazing rubble. She sees her own body, lying there amid the wreckage, pelted with burning debris, eyes wide but unseeing. She sees—

Stillness is death to a Stone Man. You have to keep moving, keep the blood flowing, the muscles moving. If you don’t, those veins and arteries will become carved channels through hard stone, the muscles will turn to useless inert rocks. Spar is never motionless, even when he’s standing still. He flexes, twitches, rocks—yes, rocks, very funny—from foot to foot. Works his jaw, his tongue, flicks his eyes back and forth. He has a special fear of his lips and tongue calcifying. Other Stone Men have their own secret language of taps and cracks, a code that works even when their mouths are forever frozen in place, but few people in the city speak it.

So when they hear the thunderclap or whatever-it-was, Spar’s already moving. Rat’s faster than he is, so Spar follows as best he can. His right leg drags behind him. His knee is numb and stiff behind its stony shell. Alkahest might cure it, if he gets some in time. The drug’s expensive, but it slows the progress of the disease, keeps flesh from turning to stone. It has to be injected subcutaneously, though, and more and more he’s finding it hard to drill through his own hide and hit living flesh.

He barely feels the heat from the blazing courtyard, although he guesses that if he had more skin on his face it’d be burnt by contact with the air. He scans the scene, trying to make sense of the dance of the flames and the fast-moving silhouettes. Rat vanishes across a rooftop, pursued by a Tallowman. Cari … Cari’s there, down in the wreckage of the tower. He stumbles across the yard, praying to the Keepers that she’s still alive, expecting to find her beheaded by a Tallowman’s axe.

She’s alive. Stunned. Eyes wide but unseeing, muttering to herself. Nearby, a pool of liquid and a burning wick, twisting like an angry cobra. Spar stamps down on the wick, killing it, then scoops Cari up, careful not to touch her skin. She weighs next to nothing, so he can easily carry her over one shoulder. He turns and runs back the way he came.

Lumbering down the corridor, not caring about the noise now. Maybe they’ve got lucky; maybe the fire drove the Tallowmen away. Few dare face a Stone Man in a fight, and Spar knows how to use his strength and size to best advantage. Still, he doesn’t want to try his luck against Tallowmen. Luck is what it would be—one hit from his stone fists might splatter the waxy creations of the alchemists’ guild, but they’re so fast he’d be lucky to land that one hit.

He marches past the first door out onto the street. Too obvious.

He stumbles to a huge pair of ornate internal doors and smashes them to flinders. Beyond is a courtroom. He’s been here before, he realises, long ago. He was up there in the viewer’s gallery when they sentenced his father to hang. Vague memories of being dragged down a passageway by his mother, him hanging off her arm like a dead weight, desperate to stay behind but unable to name his fear. Heinreil and the others, clustering around his mother as an invisible honour guard, keeping the press of the crowd away from them. Old men who smelled of drink and dust despite their rich clothes, whispering that his father had paid his dues, that the Brotherhood would take care of them, no matter what.

These days, that means alkahest. Spar’s leg starts to hurt as he drags it across the court. Never a good sign—means it’s starting to calcify.

“Hold it there.”

A man steps into view, blocking the far exit. He’s dressed in leathers and a grubby green half-cloak. Sword and pistol at his belt, and he’s holding a big iron-shod staff with a sharp hook at one end. The broken nose of a boxer. His hair seems to be migrating south, fleeing his balding pate to colonise the rich forest of his thick black beard. He’s a big man, but he’s only flesh and bone.

Spar charges, breaking into a Stone Man’s approximation of a sprint. It’s more like an avalanche, but the man jumps aside and the iron-shod staff comes down hard, right on the back of Spar’s right knee. Spar stumbles, crashes into the doorframe, smashing it beneath his weight. He avoids falling only by digging his hand into the wall, crumbling the plaster like dry leaves. He lets Cari tumble to the ground.

The man shrugs his half-cloak back, and there’s a silver badge pinned to his breast. He’s a licensed thief-taker, a bounty hunter. Recovers lost property, takes sanctioned revenge for the rich. Not regular city watch, more of a bonded freelancer.

“I said, hold it there,” says the thief-taker. The fire’s getting closer—already, the upper gallery’s burning—but there isn’t a trace of concern in the man’s deep voice. “Spar, isn’t it? Idge’s boy? Who’s the girl?”

Spar responds by wrenching the door off its hinges and flinging it, eight feet of heavy oak, right at the man. The man ducks under it, steps forward and drives his staff like a spear into Spar’s leg again. This time, something cracks.

“Who sent you here, boy? Tell me, and maybe I let her live. Maybe even let you keep that leg.”

“Go to the grave.”

“You first, boy.” The thief-taker moves, almost as fast as a Tallowman, and smashes the staff into Spar’s leg for the third time. Pain runs up it like an earthquake, and Spar topples. Before he can try to heave himself back up

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...