- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

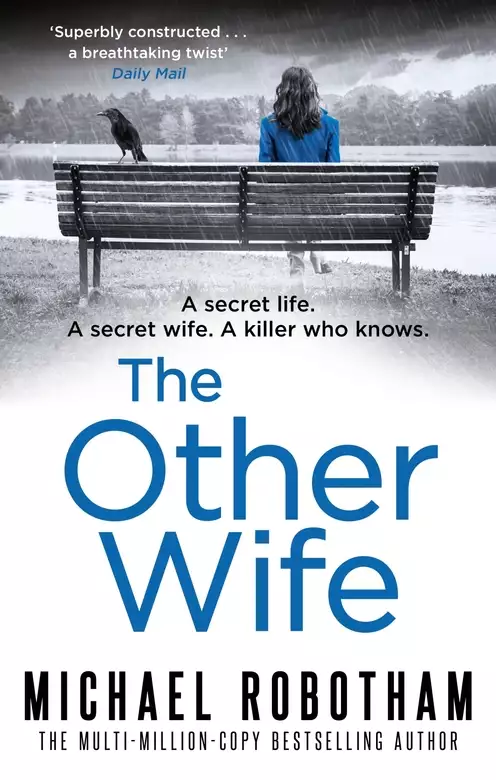

Synopsis

Childhood sweethearts William and Mary have been married for sixty years. William is a celebrated surgeon, Mary a devoted wife. Both have a strong sense of right and wrong. This is what their son, Joe O'Loughlin, has always believed. But when Joe is summoned to the hospital with news that his father has been brutally attacked, his world is turned upside down. Who is the strange woman crying at William's bedside, covered in his blood - a friend, a mistress, a fantasist or a killer? Against the advice of the police, Joe launches his own investigation. As he learns more, he discovers sides to his father he never knew - and is forcibly reminded that the truth comes at a price.

Release date: June 26, 2018

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Other Wife

Michael Robotham

I love this city. Built upon the ruins of the past, every square foot of it has been used, re-used, flattened, bombed, dismantled, rebuilt and flattened again until the layers of history are like sediments of rock that one day will be picked over by future archaeologists and treasure hunters.

I am no different – a broken man, built upon the wreckage of my past. It has been thirteen years since I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. It began with an unconscious, random flicker of my fingers on my left hand; a ghost movement that looked like a twitch, but read like a guilty verdict. Unknown to me, working in secret, my body had begun a long, drawn-out separation from my mind; a divorce where nobody gets to keep the record collection or fights over who gets the dog.

That small rolling of the thumb and forefinger has now spread silently through my limbs until they no longer do my bidding without the assistance of drugs. When I’m medicated properly, I can appear to be almost symptom-free. A little stooped and more deliberate in my movements but normal in most respects. At other times, Mr Parkinson is a cruel puppeteer, tugging at invisible strings, making me dance to music that only he can hear.

There is no cure – not yet – but I live in hope that science will win the race. In the meantime, daily exercise is recommended. That’s why I’m standing here, with all of London’s mangled and magnificent history on display. My eyes sweep from east to west and settle on the curved rooftops and netting of London Zoo. Julianne and I bought our first house a few streets from here. We would lie in bed on warm nights when the curtains swayed from open windows, listening to the calls of lions and hyenas and animals we couldn’t name.

It is sixteen months since she died. A surgical complication, they said; a blood clot that travelled from her groin to her heart and lodged in her left ventricle. She lived for a week on life support, lying on white sheets, looking tranquil and beautiful, but ‘not at home’, according to the neurologist. We turned off the machines and she slipped away like an empty rowing boat cut loose in the current.

The seasons since then have been like stages of grieving. Summer passed in denial and isolation, autumn brought anger, winter blame and by spring my depression had driven me to seek help.

I endure for the sake of my daughters, Charlie and Emma, because they deserve more than tragedy as their template and so much of Julianne lives within them; from the parting of their hair, to the inflection in their voices and the way they walk, frown and laugh.

We moved back to London a year ago, after selling the cottage in Somerset. I used the money from the sale and a bank loan to buy a top-floor flat in a mansion block called Wellington Court in Belsize Park, not far from Primrose Hill. Airy and bright, with high ceilings and a large bay window in the sitting room, it has three bedrooms and a small roof terrace, accessible from the kitchen window, where Emma and I sometimes watch the sun setting over London while sitting on deckchairs like passengers on an ocean liner.

Emma is twelve. I left her sleeping at the flat with an alarm set for school. No longer my little girl, she’s on the cusp of womanhood, with green-grey eyes, curly hair and skin so pale it looks almost powdered like a kabuki dancer. In January she started at North Bridge House, an independent day school in North London with the sort of fees to make my eyes water. The scholarship came as a bonus and a surprise.

My eldest, Charlie, is in her second year at Oxford studying behavioural psychology. Parents are normally proud when children follow in their footsteps, but I take no pleasure in Charlie wanting to be a forensic psychologist, because I know where her fascination lies and how it started. She wants to understand why some people commit terrible acts and fantasise about even worse crimes; the psychopaths and sociopaths who haunt her nightmares.

Continuing down the hill, I cross the canal into Regent’s Park. A young woman jogs past me, her buttocks hugged by Lycra and her ponytail bobbing on her back. I contemplate catching up with her. We could run together. Connect. I’m dreaming. She’s gone.

I have an appointment this morning with Dr Victoria Naparstek at a café not far from her office in Harley Street. Victoria is a good-looking woman. Forty-something. Slim. Striking. I slept with her once when Julianne and I were separated. Victoria broke it off. When I asked her why, she said, ‘You’re still in love with your wife.’ I asked her if that mattered. ‘It does to me,’ she replied.

She’s waiting for me at a café in Portland Place. Dressed in an A-line skirt and matching jacket with a simple white blouse, open at the neck. She smiles and her dimples leave an impression on her cheeks.

‘Professor O’Loughlin.’

‘Dr Naparstek.’

‘You’re sweaty.’

‘See what you do to me.’

We banter. Flirt a little. A waitress has come to take our order. Tea. Coffee. Toast. Jam.

Everybody told me that I should talk to someone after Julianne’s death. I know the benefits of grief counselling, yet I fought against the idea until Victoria called me a ‘fucking idiot’ and a ‘typical man’ who shuts down and pretends the problem doesn’t exist.

‘You look good,’ she says.

‘I am.’

My first lie.

‘Have you been sleeping?’

‘Yes.’

Another one.

‘And the dreams?’

‘One or two.’

‘Always the same?’

I nod.

This is part of our routine. Therapy without being therapy. She will quiz me, I will answer, and neither of us will feel under any obligation to reveal confidences or offer advice.

Victoria wants me to verbalise my worst fears, but I don’t have to put them into words because I live them every day. I don’t have to imagine being alone, or having an illness, or suddenly bursting into tears over a broken cup, or a dropped egg.

‘How is Emma?’ she asks.

‘Good. Better. We spent yesterday painting her room and putting stencils on the walls.’

‘Did she mention Julianne?’

‘No.’

‘What about the photographs?’

‘She won’t look at them.’

Emma hasn’t cried or rebelled or asked questions about her mother’s death. She won’t visit Julianne’s grave, or look at photographs of her, or reminisce about the past. This isn’t about denial, or pretending nothing has changed. Emma knows that Julianne isn’t coming back, but refuses to labour the point, or have it define our existence.

Some nights, I’ve found her hiding in her wardrobe, curled in a ball.

‘What’s wrong?’

‘I can’t sleep.’

‘That’s OK. Just rest your eyes.’

‘What if I never sleep again?’

‘You will.’

‘What if I’m the only one awake? The whole world will be sleeping and I’ll be on my own, in the dark … with nobody to help me.’

‘I’ll be here.’

‘Promise you won’t fall asleep until I do.’

‘I promise.’

Emma worries about me because I am the last parent standing. When we cross the street, she insists on holding my hand – not to protect herself, but to protect me. She makes sure that I eat well and exercise and take my medication. I wake sometimes to find her leaning over my bed with her hand on my chest. She counts the number of breaths. Three sets of nine. Twenty-seven. Usually, that’s enough to reassure her.

Our coffees have arrived. Victoria tears open a sachet of sugar and shakes the contents into the foam.

‘Did you ask Emma if she’d talk to me?’

‘She’s not sold on the idea.’

‘I understand.’

‘I don’t want to push her.’

‘You shouldn’t. Let her make the decision when she’s ready.’

I’ve given the same advice to countless grieving parents when they’ve visited my consulting rooms, but when it comes to my own flesh and blood I begin to question my thirty years of clinical experience as a psychologist.

My mobile phone is vibrating on the table. I don’t recognise the number.

‘Is that Professor O’Loughlin?’ asks a female voice.

‘Yes.’

‘This is the registrar at St Mary’s Hospital in Paddington. Your father, William O’Loughlin, has been admitted with serious head injuries.’

‘Head injuries.’

‘He underwent surgery six hours ago.’

‘Surgery.’

‘To relieve pressure on his brain. He was bleeding internally. Right now he’s in a medically induced coma.’

‘Coma.’

Why am I repeating everything she says?

The café has a shelf of bonsai plants, miniature trees with gnarled trunks and moss-covered branches. I find myself staring at the shrunken forest, no longer listening to what the registrar is saying. My knees are shaking.

‘Are you there, Professor?’

‘Yes. Sorry. What was my father doing in London?’

What difference does it make?

‘I don’t have that information,’ replies the registrar.

Of course she doesn’t! It’s a stupid question.

‘Does my mother know?’

‘She’s with him now.’

‘Can I talk to her?’

‘We don’t allow mobile phones in the ICU.’

‘I see. Right. Tell her I’m coming.’

I end the call and stare at the blank screen. I should call my sisters. No, Mum will have done that. I should catch a cab. Emma is at home. I’m supposed to walk her to school and then I have patients to see. I can cancel my appointments.

Victoria searches for her wallet. ‘You go. Call me later.’

Within moments I’m on the pavement, looking for a cab. Three of them pass. Occupied. I start jogging, desperately trying to lift my feet and swing my arms in sequence. Traffic is backed up along Euston Road. I cut across Regent’s Park and up Primrose Hill. My lungs hurt and lactic acid is building up in my legs.

Having climbed the stairs at Wellington Court, I’m ready to collapse.

‘Did you run all the way?’ asks Emma, who is sitting at the kitchen bench, in her school uniform – a striped dress, red cardigan, black tights and buckled shoes.

‘Granddad … in hospital … I have to go.’

‘What happened?’

‘Some sort of accident. I need a shower.’

‘Is he going to be OK?’

‘He’s in good hands.’

Emma follows me down the hallway. ‘Bad things happen at hospitals.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘People die.’ Her lips are pulled down at the corners and her tea-coloured eyes are shining.

‘Not always. Most of them get better,’ I say, knowing that my words sound hollow to someone who has lost her mother.

‘I don’t want you to go,’ she says.

‘Nothing is going to happen to me.’

‘At least let me come.’

‘You have school.’

‘Who’s going to take me?’

‘I’ll talk to the boys.’

The boys are men – Duncan and Arturo – a gay couple who live on the floor below. One works in advertising and the other runs an art gallery in Islington. Having showered and changed, I knock on their door. Duncan answers. He’s wearing a short gown just long enough to brush the top of his thighs.

‘Joseph,’ he says excitedly, kissing both my cheeks. I bend in the middle to avoid groin-to-groin contact.

‘My dad is in hospital. Can one of you take Emma to school?’

Duncan relays the message over his shoulder and Arturo replies, yelling from the kitchen. ‘I can take her on the back of my bike.’

I want to say no. Duncan does it for me. ‘You’re not taking her on the bike. You ride like a maniac.’

‘I did a safe-riding course.’

‘With Evel Knievel.’

I’ve triggered a domestic dispute. Duncan waves me away. ‘You go, I’ll walk her. I hope your father is all right.’

Minutes later I’m in a cab, stuck in traffic on Edgware Road, listening to the talkback callers complaining about Brexit, ‘fake news’, immigrants and low wages. I’ve grown tired of politics and current affairs. I don’t want to be informed by journalists or governed by politicians of any persuasion. Democracy has failed. Let’s try a benign dictatorship.

My father is in a coma. He turned eighty this year and I don’t remember him ever being in hospital – not as a patient. I long ago labelled him ‘God’s-Personal-Physician-in-Waiting’ because of his indefatigable energy and unrivalled self-belief. For more than fifty years he was a medical giant – a professor of surgery and public health; advisor to governments, founder of the International Trauma Research Unit, lecturer, author, commentator and philanthropist. Our family’s charitable trust – the O’Loughlin Foundation – gives millions of pounds in research grants each year.

I saw Dad two weeks ago. We had lunch at his club in Mayfair; a pleasant enough two hours in a tweedy, pass-the-port sort of way. I don’t remember what we spoke about. Nothing meaningful. He looked well. Happy. He spends most of his time at the farmhouse in Wales, but comes to London quite regularly for meetings and lectures.

The cab arrives at St Mary’s and I hurry past a cluster of nurses and orderlies, smoking cigarettes on the pavement. The Major Trauma Ward is on the ninth floor. Waiting for the lift to arrive, I catch that hospital smell of antiseptic, floor polish and bodily fluids. Memories bubble up and scald my throat. Swallowing hard, I force them down, tasting the vomit.

I press a buzzer outside the ICU. A nursing sister answers, the heavy door sucking inwards like she’s opening an airlock.

‘My father is here. William O’Loughlin. My mother is with him.’

Her smile is encouraging. I wonder how long she’s practised it.

‘Please wash your hands,’ she says, showing me to a sink with antibacterial soap and a paper towel dispenser. I follow her through a long dimly lit ward past rows of beds partitioned by machines and curtains. Each pool of light contains someone who is close to death, plugged in, taped up, filled and drained, hydrated and evacuated, medicated and sedated.

‘He’s the last cubicle,’ says the nurse. ‘Please don’t try to wake him.’

I approach tentatively, catching my first glimpse of a broken man lying on a bed, imprisoned by tubing and cables. His head is heavily bandaged. An oxygen mask covers his mouth. IV bags hang above his head. Needles have been driven into his veins. Sensors are monitoring his vital signs.

I want to turn back and say, ‘That’s not my father. There’s been a mistake,’ but I know it’s him.

A woman is sitting beside the bed, partially in shadow. She looks up as though startled, her eyes red-rimmed and bruised from lack of sleep.

Letting go of Dad’s hand, she gets to her feet.

‘It’s Joseph, isn’t it?’

I nod.

‘I didn’t want us to meet like this.’

‘I don’t understand. Where’s my mother?’

‘She’s not here.’

‘But I was told …’

‘I asked the hospital to call you.’

‘I’m sorry, but who are you?’

‘I’m his other wife.’

How long do I stand there, unable to speak? I laugh uncomfortably, which is supposed to be her cue to say that she’s joking. She doesn’t take it. I look feeble and embarrassed, growing angry at her silence. What sort of cruel joke is this? Where are the hidden cameras? When will someone jump out and yell, ‘April Fool!?’ Only it’s November not April and I don’t think I’m a fool.

The man in bandages is my father. The woman next to him is not my mother.

‘I’m Olivia Blackmore,’ she says, offering her hand.

I look at her outstretched fingers as though she’s pointing a gun.

‘I think you’ve made a mistake,’ I say. ‘How did you get my number?’

‘William told me that if something like this happened, I was to call you first.’

‘Something like what?’

‘An accident or an emergency.’

In her forties with dark hair and the remnants of make-up, she has a slight accent, East European perhaps, which has faded over time. She’s wearing high-heeled shoes, dark tights and a loosely belted trench coat.

‘I was told my mother was here …’

‘The nurse misunderstood me.’

I’m searching for words in vain. ‘Is my mother coming?’

‘No.’

I start again. ‘What happened to him?’

‘I found him at the bottom of the stairs.’

‘What stairs?

‘At the house.’

‘Whose house?’

‘Ours.’

‘Who are you?’

‘I’m his wife.’

‘He’s already married.’

‘His other wife.’

‘You’re his mistress?’

‘No.’

It’s a fatuous conversation. I want to stop myself. Why am I deigning to talk to her? Clearly, she’s crazy. How did she get past security?

I try again. ‘He can only have one wife. Are you saying he’s a bigamist?’

Olivia shakes her head. ‘I’m sorry, Joseph, I’m not making myself very clear. I know this comes as a shock. Your father, William, made a commitment to me. We married in Bali. It was a Buddhist ceremony.’

‘He’s never been to Bali.’

‘You’re mistaken.’

‘He isn’t a Buddhist.’

‘No,’ she replies, ‘but I am.’

Is a Buddhist marraige legally recognised in the UK, I wonder. My body chooses this moment to freeze. It does that occasionally – locks up or seizes completely as though playing a game of musical statues and someone has stopped the music.

‘Do you need your medication?’

How does she know about that?

‘I can get you some water.’ She touches my forearm.

‘No!’ I snap, brushing her hand away.

Olivia steps back as though suddenly frightened of me. She resumes her seat, reaching across the sheet to hold Dad’s hand.

‘I don’t want you touching him.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘Get your hands off him or I’ll call the police.’

‘Go ahead.’

It occurs to me that nobody has contacted my mother. I take out my phone.

‘You can’t use that in here,’ says Olivia, pointing to a sign. ‘You’ll have to go outside.’

I step closer to the bed, whispering angrily, ‘I don’t know who you are, or why you’re here, but my father and my mother have been married for sixty years. He doesn’t have “other wives”.’

‘Just me,’ she says softly.

‘I want you to leave,’ I say, furious with her.

‘Please don’t raise your voice.’

‘I’ll do as I damn well please.’

An ICU nurse arrives, drawn by our argument. Moon-faced and pretty, with dreadlocked hair, she tells us both to be quiet.

‘This woman is not my mother,’ I tell her. ‘She’s tricked her way in.’

The nurse looks at Olivia suspiciously. ‘Is that true?’

‘No, I’m his wife.’

‘I’ve never seen her before,’ I say. ‘I want her out of here.’

Olivia pleads: ‘I know you’re upset, Joseph, but don’t do this. Go and call your mother. I’ll sit with William.’

Her belted coat has fallen open. Underneath she’s wearing a pale green cocktail dress stained by something darker.

‘Is that blood?’

She closes the coat. ‘I found him. He was lying at the bottom of the stairs.’

‘Where?’

‘I told you. At the house in Chiswick. It’s where we live.’

I shake my head. ‘No! No! No!’

‘I’m telling you the truth.’

‘You’re delusional.’

The nurse has heard enough. ‘I want you both to leave.’

‘Please. We’ll be quiet,’ says Olivia.

‘I’m calling security,’ says the nurse. ‘They can sort this out.’

‘Somebody has to stay,’ says Olivia, looking at Dad.

‘No! Both of you get out.’ She’s not going to change her mind.

Olivia collects her handbag from beneath the chair. I wait for her to leave first in case she tries something. I don’t know what I expect – she could sabotage the machines or smother Dad with a pillow.

The ICU doors close behind us. Olivia takes a tissue from her coat pocket and blows her nose. ‘I have heard so many good things about you Joseph, but I didn’t think you’d be so cruel.’

She pauses, making sure I’ve heard, before moving away and taking a seat further along the corridor. She searches her handbag and finds another tissue.

I call my mother’s number. The phone rings. I picture her padding down the hallway at the farmhouse in Wales, picking up the receiver, using her posh-sounding phone voice. But there’s no answer. She has a mobile phone. I try the number.

She answers, shouting to be heard above the background noise.

‘Joseph?’

‘Where are you?’

‘I’m on the train.’

‘Are you coming to London?’

‘No. Why?’

‘Dad is in hospital. Intensive care.’

I hear her sudden inhalation.

‘He’s in the ICU. They operated last night. I’m here now. I thought they might have called you.’

‘No.’ Her voice is trembling.

‘He has head injuries. I don’t know all the details. You should be here.’

‘Yes, of course … I’ll … I’ll …’

‘What was Dad doing in London?’ I ask.

‘He had a board meeting. He left yesterday. What happened?’

‘I think he fell down the stairs.’

‘Do the girls know?’

She’s talking about my sisters: Lucy, Patricia and Rebecca.

‘I’m going to call them.’

‘Please don’t leave your father alone,’ she says. ‘Stay with him.’

‘I will.’

After ending the call, I glance up and see two police officers emerge from the lifts – one in uniform and the other in plain clothes. The detective is older and heavier with wire-rimmed glasses and Nordic features. He talks to a nurse, who points them along the corridor in my direction. I wait for them, but they’re not looking for me. They stop at Olivia, who looks up from her phone. I can’t hear the conversation, but I see her grow agitated. She’s been busted! Exposed as a liar. Good! In the same instant I see hurt rather than fear in her eyes.

They’re preparing to leave. Olivia looks at her feet, as though she might have dropped something.

‘Where are you taking her?’ I ask, having moved closer.

The detective turns to face me, setting his legs apart. ‘What’s your name, sir?’

‘Joseph O’Loughlin.’

‘Are you related to William O’Loughlin?’

‘He’s my father.’

‘Can I see some identification?’

I show him my driver’s licence.

He motions to Olivia Blackmore. ‘Do you know this woman?’

‘No.’

‘Have you ever seen her before?’

‘Never. Why?’

The detective ignores the question and turns away, walking towards the lift. I follow. ‘What happened to him? Was it an accident?’

Neither officer breaks stride. They’re at the lift. I stop the doors from closing.

‘Did she do this?’

‘Please, step back,’ says the detective.

‘Where are you taking her?’

‘Chiswick police station.’

The doors are closing. Olivia raises her eyes to mine.

‘If he wakes up, tell him … tell him … I love him.’

My eldest sister Lucy lives in Henley, west of London, with her husband Eric, an air-traffic controller, and their three children whose names I can never remember because they all end in the same ‘ee’ sound. I punch out her number and listen to it ringing.

Lucy answers. My left arm trembles. She’s in the car. The school run.

‘Can you talk?’

‘I’m on the hands-free. What’s wrong?’

‘Dad is in hospital. He had some sort of accident. They operated last night to relieve pressure on his brain.’

Her voice changes, rising higher. ‘Was he driving?’

‘A fall, I think. He’s at St Mary’s in Paddington.’

‘Have you talked to him?’

‘He’s in a coma.’

‘Christ! Where’s Mummy?’

‘She’s catching a train.’

‘What about Patricia and Rebecca?’

‘I called you first.’

Lucy is the natural leader among my siblings – the competent, organised figure who arranges family gatherings, remembers birthdays and coordinates our ‘secret Santa’ present-buying each Christmas. Patricia, my middle sister, lives in Cardiff with her husband Simon, a criminal barrister. Rebecca, the youngest girl, is a high achiever who works for the World Bank in Geneva. I’m the baby of the family – the long-awaited boy, although not the Little Prince. I abdicated that position when I chose to become a psychologist rather than a surgeon, ending a medical dynasty that dated back more than a century.

‘I’ll call Patricia,’ says Lucy, taking charge. ‘Rebecca is in South Sudan. You might reach her on her mobile. I’ll be there as soon as I can.’

After Lucy hangs up, I call Rebecca’s mobile and leave a message, giving her the briefest of details, telling her not to worry and to call me. What should I do next? There must be other friends or family I can contact, but I don’t want to share the news, not yet. Functioning on a kind of autopilot, I stare out the window at a skyline dotted with cranes and half-built office towers. Pigeons wheel across a pale blue sky that is marked by the chalk-like smudges of jets travelling in the troposphere. A day like this should be darker and bleak. It should mirror the news or my mood.

Returning to the ICU, I sit beside Dad and take his hand – something I haven’t done since I was a child. Did I do it as a child? I must have done.

I study his face. His hair, so white and thick, was dyed until his mid-fifties, but turned white overnight when he threw away the bottle and aged as gracefully as he lived. A stranger might believe the wrinkles around his eyes were laughter lines, but the runnels are deepest where his skin has folded most often, perfectly illustrating his complaining nature and general dissatisfaction with people, particularly his children, most notably me.

This feels strange, being so intimate. I don’t think in my entire life I have spent ten minutes alone with Dad when he didn’t demean, belittle or insult me. Maybe that’s an exaggeration, but his opinions were mostly disapproving or judgemental. Children were to be seen and not heard. Never mollycoddled or over-praised.

There is no lightness about my father, no play or mischief. Growing up, I don’t remember him singing ditties or doing silly dances or acting the goat. He didn’t chase us around the garden, or play hide and seek, or put on funny voices. He didn’t get us dressed or make us breakfast or drop us at school, or drive us to sport, or listen to us practise piano, or help with our homework. When we fell over and hurt ourselves, none of us ran to Dad, or cried his name, or crawled on to his lap.

I’m not saying he neglected us. Others fulfilled these tasks: my mother, nannies, au pairs or housekeepers. Dad was needed elsewhere. Required by the wounded or broken or diseased. He saved lives. He pioneered surgical techniques. He battled infections that ate children and illnesses that tore families apart.

Some women are referred to being ‘natural mothers’ and men as being ‘natural fathers’. I don’t know what that means. My father is simply my father. Stiff. Self-conscious. Opinionated. Cantankerous. Demanding. Absent.

Even when home, he would spend long hours in his study. If we were playing in the garden, we knew to keep the noise down or risk having him open the window and bellow for us to be quiet. One time Rebecca peed her pants at the sound of his voice, although she was notorious for peeing her pants when she got too excited.

When I was eight or nine I complained of being hungry and Dad denied me food all day so I could experience deprivation and appreciate the most basic of elements. Another time, when I forgot to keep the wood-fired Aga alight, he made everyone eat a cold supper, insisting my sisters ‘share’ my punishment.

Where was my mother in all this? In the middle. Keeping the peace.

She hugged, kissed, bathed, bandaged and mended. She told us every day that Dad loved us and made us say prayers for him.

As a boy, I realised very quickly that Dad wasn’t like other fathers.

At social gatherings, he didn’t stand around the barbecue, drinking beer and turning sausages, talking cricket or rugby. He stood on the fringes, a glass of fizzy water in his hand, wearing. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...