- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

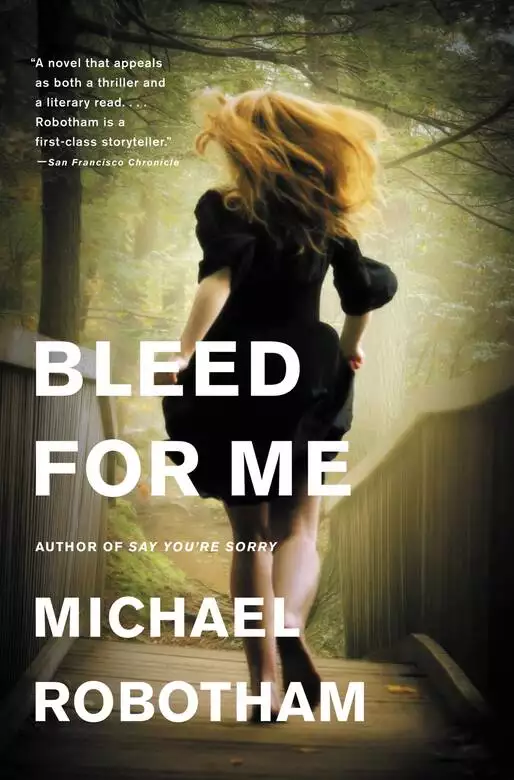

Synopsis

She's standing at the front door. Covered in blood. Is she the victim of a crime? Or the perpetrator?

A teenage girl--Sienna, a troubled friend of his daughter--comes to Joe O'Loughlin's door one night. She is terrorized, incoherent-and covered in blood.

The police find Sienna's father, a celebrated former cop, murdered in the home he shared with Sienna. Tests confirm that it's his blood on Sienna. She says she remembers nothing.

Joe O'Loughlin is a psychologist with troubles of his own. His marriage is coming to an end and his daughter will barely speak to him. He tries to help Sienna, hoping that if he succeeds it will win back his daughter's affection. But Sienna is unreachable, unable to mourn her father's death or to explain it.

Investigators take aim at Sienna. O'Loughlin senses something different is happening, something subterranean and terrifying to Sienna. It may be something in her mind. Or it may be something real. Someone real. Someone capable of the most grim and gruesome murder, and willing to kill again if anyone gets too close.

His newest thriller is further evidence that Michael Robotham is, as David Baldacci has said, "the real deal--we only hope he will write faster."

Release date: February 27, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Bleed For Me

Michael Robotham

As defining events go, nothing else comes close for Liam, not the death of his mother or his faith in God or the three years he has spent in a secure psychiatric hospital—all of which can be attributed, in one way or another, to that moment of madness in a cinema queue.

“That moment of madness” is the term his psychiatrist just used. Her name is Dr. Victoria Naparstek and she’s giving evidence before a Mental Health Review Tribunal, listing Liam’s achievements as though he’s about to graduate from university.

Dr. Naparstek is a good-looking woman, younger than I expected; midthirties with honey-blond hair, brushed back and gathered in a tortoiseshell clasp. Strands have pulled loose and now frame her features, which otherwise would look quite elfin and sharp. Despite her surname, her accent is Glaswegian but not harsh or guttural, more a Scottish lilt, which makes her sound gay and carefree, even when a man’s freedom is being argued. I wonder if she’s aware that her eyes devour rather than register a person. Perhaps I’m being unfair.

Liam is sitting on a chair beside her. It has been four years since I saw him last, but the change is remarkable. No longer awkward and uncoordinated, Liam has put on weight and his glasses are gone, replaced by contact lenses that make his normally pale blue eyes appear darker.

Dressed in a long-sleeved cotton shirt and jeans, he wears shoes with pointed toes, which are fashionable and he has gelled his hair so that it pokes towards the ceiling. I can picture him getting ready for this hearing, taking extra care with his appearance because he knows how important it is to look his best.

Out the window I can see a walled courtyard, dotted with potted plants and small trees. A dozen patients are exercising, each inhabiting a different space, without acknowledging the others’ existence. Some take a few strides in one direction and then stop, as though lost, and start in a different direction. Others are swinging their arms and marching around the perimeter as though it is a parade ground. One young man seems to be addressing an audience while another has crawled beneath a bench as if sheltering from an imaginary storm.

Dr. Naparstek is still talking.

“In my months working with Liam, I have discovered a troubled young man, who has worked very hard to better himself. His anger issues are under control and his social skills are greatly improved. For the past four months he has been part of our shared-house program, living cooperatively with other patients, cooking, cleaning and washing, making their own rules. Liam has been a calming influence—a team leader. Recently, we had a critical incident when a male resident took a hostage at knifepoint and barricaded a door. It took five minutes for security to gain access to the shared house, by which time Liam had defused the situation. It was amazing to watch.”

I glance at the three members of the review tribunal—a judge, a medical specialist and a lay person with mental health experience. Do they look “amazed,” I wonder. Perhaps they’re just not showing it.

The tribunal must decide if Liam should be released. That’s how the system works. If an offender is thought to be cured, or approaching being cured, they are considered for rehabilitation and release. From a high-security hospital they’re transferred to a regional secure unit for further treatment. If that goes well, they are given increasing amounts of leave, first in the grounds of the unit and later in the local streets with an escort, and then alone.

I am not here in any official capacity. This should be one of my half-days at Bath University, where I’ve taught psychology for the past three years. That’s how long it’s been since I quit my clinical practice. Do I miss it? No. It lives with me still. I remember every patient—the cutters, the groomers, the addicts, the narcissists, the sociopaths and the sexual predators; those who were too frightened to step out into the world and the few who wanted to burn it down.

Liam was one of them. I guess you could say I put him here because I recommended he be sectioned and given treatment rather than sent to a regular prison.

Dr. Naparstek has finished. She smiles and leans down to whisper something in Liam’s ear, squeezing his shoulder. Liam’s eyes swim but aren’t focused on her face. He is looking down the front of her blouse. Resuming her seat, she crosses her legs beneath her charcoal-gray skirt.

The judge looks up. “Is there anyone else who would like to address the tribunal?”

It takes me a moment to get to my feet. Sometimes my legs don’t do as they’re told. My brain sends the messages but they fail to arrive or like London buses they come all at once causing my limbs to either lock up or take me backwards, sideways and occasionally forwards, so that I look like I’m being operated via remote control by a demented toddler.

The condition is known as Parkinson’s—a progressive, degenerative, chronic but not contagious disease that means I’m losing my brain without losing my mind. I will not say incurable. They will find a cure one day.

I have found my feet now. “My name is Professor Joseph O’Loughlin. I was hoping I could ask Liam a few questions.”

The judge tilts his chin to his chest. “What’s your interest in this case, Professor?”

“I’m a clinical psychologist. Liam and I are acquainted. I provided his pre-sentencing assessment.”

“Have you treated Liam since then?”

“No. I’m just hoping to understand the context.”

“The context?”

“Yes.”

Dr. Naparstek has turned to stare at me. She doesn’t seem very impressed. I make my way to the front of the room. The linoleum floor is shining as daylight slants through barred windows, leaving geometric patterns.

“Hello, Liam, do you remember me?”

“Yes.”

“Come and sit up here.”

I place two chairs facing each other. Liam looks at Dr. Naparstek, who nods. He moves forward, taller than I remember, less confident than a few minutes ago. We sit opposite, our knees almost touching.

“It’s good to see you again. How have you been?”

“Good.”

“Do you know why we’re here today?”

He nods.

“Dr. Naparstek and the people here think you’re better and it’s time you moved on. Is that what you want?”

Again he nods.

“If you are released, where would you go?”

“I’d find somewhere to live. G-g-get a job.”

Liam’s stutter is less pronounced than I remember. It gets worse when he’s anxious or angry.

“You have no family?”

“No.”

“Most of your friends are in here.”

“I’ll m-m-make new friends.”

“It’s been a while since I saw you last, Liam. Remind me again why you’re here.”

“I did a bad thing, but I’m better now.”

There it is: an admission and an excuse in the same breath.

“So why are you here?”

“You sent me here.”

“I must have had a reason.”

“I had a per-per-personality disorder.”

“What do you think that means?”

“I hurt someone, but it weren’t my fault. I couldn’t help it.” He leans forward, elbows on his knees, eyes on the floor.

“You beat a girl up. You punched and kicked her. You crushed her spine. You broke her jaw. You fractured her skull. Her name was Zoe Hegarty. She was sixteen.”

Each fact resonates as though I’m clashing cymbals next to his ear, but nothing changes in his eyes.

“I’m sorry.”

“What are you sorry for?”

“For what I d-d-did.”

“And now you’ve changed?”

He nods.

“What have you done to change?”

He looks perplexed.

“Hostility like that has to come from somewhere, Liam. What have you done to change?”

He begins talking about the therapy sessions and workshops that he’s done, the anger-management courses and social skills training. Occasionally, he looks over his shoulder towards Dr. Naparstek, but I ask him to concentrate on me.

“Tell me about Zoe.”

“What about her?”

“What was she like?”

He shakes his head. “I don’t remember.”

“Did you fancy her?”

Liam flinches. “It w-w-weren’t like that.”

“You followed her home from the cinema. You dragged her off the street. You kicked her unconscious.”

“I didn’t rape her.”

“I didn’t say anything about raping her. Is that what you intended to do?”

Liam shakes his head, tugging at the sleeves of his shirt. His eyes are focused on the far wall, as if watching some invisible drama being played out on a screen that nobody else can see.

“You once told me that Zoe wore a mask. You said a lot of people wore masks and weren’t genuine. Do I wear a mask?”

“No.”

“What about Dr. Naparstek?”

The mention of her name makes his skin flush.

“N-n-no.”

“How old are you now, Liam?”

“Twenty-two.”

“Tell me about your dreams.”

He blinks at me.

“What do you dream about?”

“Getting out of here. Starting a n-n-new life.”

“Do you masturbate?”

“No.”

“I don’t believe that’s true, Liam.”

He shakes his head.

“What’s wrong?”

“You shouldn’t talk about stuff like that.”

“It’s very natural for a young man. When you masturbate who do you think about?”

“Girls.”

“There aren’t many girls around here. Most of the staff are men.”

“G-g-girls in magazines.”

“Dr. Naparstek is a woman. How often do you get to see Dr. Naparstek? Twice a week? Three times? Do you look forward to your sessions?”

“She’s been good to me.”

“How has she been good to you?”

“She doesn’t judge me.”

“Oh, come on, Liam, of course she judges you. That’s why she’s here. Do you ever have sexual fantasies about her?”

He bristles. Edgy. Uncomfortable.

“You shouldn’t say things like that.”

“Like what?”

“About her.”

“She’s a very attractive woman, Liam. I’m just admiring her.”

I look over his shoulder. Dr. Naparstek doesn’t seem to appreciate the compliment. Her lips are pinched tightly and she’s toying with a pendant around her neck.

“What do you prefer, Liam, winter or summer?”

“Summer.”

“Day or night?”

“Night.”

“Apples or oranges?”

“Oranges.”

“Coffee or tea?”

“Tea.”

“Women or men?”

“Women.”

“In skirts or trousers?”

“Skirts.”

“Long or short?”

“Short.”

“Stockings or tights?”

“Stockings.”

“What color lipstick?”

“Red.”

“What color eyes does she have?”

“Blue.”

“What is she wearing today?”

“A skirt.”

“What color is her bra?”

“Black.”

“I didn’t mention a name, Liam. Who are you talking about?”

He stiffens, embarrassed, his face a beacon. I notice his left knee bouncing up and down in a reflex action.

“Do you think Dr. Naparstek is married?” I ask.

“I d-d-don’t know.”

“Does she wear a wedding ring?”

“No.”

“Maybe she has a boyfriend at home. Do you think about what she does when she leaves this place? Where she goes? What her house looks like? What she wears to bed? Maybe she sleeps naked.”

Flecks of white spit are gathered in the corners of Liam’s mouth.

Dr. Naparstek wants to stop the questioning, but the judge tells her to sit down.

Liam tries to turn but I lean forward and put my hands on his shoulders, my mouth close to his ear. I can see the sweat wetting the roots of his hair and a fleck of shaving foam beneath his ear.

In a whisper, “You think about her all the time, don’t you, Liam? The smell of her skin, her shampoo, the delicate shell of her ear, the shadow in the hollow between her breasts… every time you see her, you collect more details so that you can fantasize about what you want to do to her.”

Liam’s skin has flushed and his breathing has gone ragged.

“You fantasize about following her home—just like you followed Zoe Hegarty. Dragging her off the street. Making her beg you to stop.”

The judge suddenly interrupts. “We can’t hear your questions, Professor. Please speak up.”

The spell is broken. Liam remembers to breathe.

“My apologies,” I say, glancing at the review panel. “I was just telling Liam that I might ask Dr. Naparstek out to dinner.”

“B-b-but y-y-you’re married.”

He noticed my wedding ring.

“I’m separated. Maybe she’s available.”

Again, I lean forward, putting my cheek next to his.

“I’ll take her to dinner and then I’ll take her home. I bet she’s a dynamite fuck, what do you think? The prim and proper ones, all cool and distant, they go off like chainsaws. Maybe you want to fantasize about that.”

Liam has forgotten to breathe again. His brain is sizzling in an angry-frantic way, screaming like a guitar solo.

“Does that upset you, Liam? Why? Let’s face it, she’s not really your type. She’s pretty. She’s educated. She’s successful. What would she want with a sad, sadistic fuck like you?”

Liam’s eyes jitter back and forth like a shot of adrenaline has punched straight into his brain. He launches himself out of his seat, taking me with him across the room. The world is flying backwards for a moment and his thumbs are in my eye sockets and his hands squeezing my skull. I can barely hear a thing above my own heartbeat until the sound of heavy boots on the linoleum.

Liam is dragged off me, panting, ranting. Hospital guards have secured his arms, lifting him bodily, but he’s still lashing out at me and screaming, telling me what he’s going to do.

The tribunal members have been evacuated or sought refuge in another room. I can still hear Liam being wrestled down a distant corridor, kicking at the walls and doors. Victoria Naparstek has gone with him, trying to calm him down.

My eyes are streaming and through closed lids I can see a kaleidoscope of colored stars merging and exploding. Dragging myself to a chair, I pull out a handkerchief to wipe my cheeks. After a few minutes I can see clearly again.

Dusting off my jacket, I pick up my battered briefcase and make my way through the security stations and locked doors until I reach the parking area where my old Volvo estate looks embarrassingly drab. I’m about to unlock the door when Victoria Naparstek appears, moving unsteadily in high heels over the uneven tarmac.

“What the hell was that? It was totally unprofessional. How dare you talk about what I wear to bed! How dare you talk about my underwear!”

“I’m sorry if I offended you.”

“You’re sorry! I could have you charged with misconduct. I should report you to the British Psychological Society.”

Her brown irises are on fire and her nostrils pinched.

“I’m sorry if you feel that way. I simply wanted to see how Liam would react.”

“No, you wanted to prove me wrong. Do you have something against Liam or against me?”

“I don’t even know you.”

“So it’s Liam you don’t like?”

The accusation clatters around my head and my left leg spasms. I feel as though it’s going to betray me and I’ll do something embarrassing like kick her in the shins.

“I don’t like or dislike Liam. I just wanted to make sure he’d changed.”

“So you tricked him. You belittled him. You bullied him.” She narrows her eyes. “I’ve heard people talk about you, Professor O’Loughlin. They always use hushed tones. I had even hoped I might learn something from you today. Instead you bullied my patient, insulted me and revealed yourself to be an arrogant, condescending, misogynistic prick.”

Not even her Scottish lilt can make this sound gay or carefree. Up close she is indeed a beautiful woman. I can see why a man might fixate upon her and ponder what she wears in bed and what sounds she makes in the throes of passion.

“He’s devastated. Distraught. You’ve set back his rehabilitation by months.”

“I make no apologies for that. Liam Baker has learned to mimic helpfulness and cooperation, to pretend to be better. He’s not ready to be released.”

“With all due respect, Professor…”

Whenever anyone begins a sentence like this I brace myself for what’s coming.

“… I’ve spent the past eighteen months working with Liam. You saw him half a dozen times before he was sentenced. I think I’m in a far better position to judge his progress than you are. I don’t know what you whispered to Liam, but it was completely unfair.”

“Unfair to whom?”

“To Liam and to me.”

“I’m trying to be fair to Zoe Hegarty. You might not agree with me, Doctor, but I think I just did you an enormous favor.”

She scoffs. “I’ve been doing this job for ten years, Professor. I know when someone poses a danger to society.”

I interrupt her. “It’s not society I’m worried about. It’s far more personal than that.”

Dr. Naparstek hesitates for a moment. I can almost picture her mind at work—her prefrontal cortex making the connections between Liam’s words, his stolen glances and his knowledge of her underwear and where she lives. Her eyes widen as the realization reaches her amygdala, the fear center.

The Volvo starts first time, which makes it more reliable than my own body. As the boom gate rises, I catch a glimpse of the doctor still standing in the car park staring after me.

The grounds of Shepparton Park School are bathed in the spring twilight with shadows folding between the trees. Most of the buildings are dark except for Mitford Hall, where the windows are brightly lit and young voices are raised.

I’m early to pick up Charlie. The rehearsals haven’t finished. Slipping through a side door, I hide in the darkness of the auditorium, gazing across rows of empty seats to the brightly lit stage.

School musicals and dance recitals are a rite of passage for every parent. Charlie’s first performance was eight years ago, a Christmas pageant in which she played a very loud cow. Now she’s fourteen with bobbed hair and dressed in a twenties flapper dress, having been transformed into Miss Dorothy Brown, the best friend of Thoroughly Modern Millie.

I could never do it myself—tread the boards. My only theatrical appearance was aged five in a primary school production of The Sound of Music when I was cast as the youngest von Trapp child (normally a girl, I know, but size rather than talent won me the part). I was small enough to be carried upstairs by the girl who played Liesl (Nicola Bray in year six) when the von Trapp children sang “So Long, Farewell.” I was in love with Nicola and wanted her to carry me to bed every night. That was forty-four years ago. Some crushes don’t get crushed.

I recognize some of the cast, including Sienna Hegarty, who is in the chorus. She desperately wanted to play the lead role of Millie Dillmount, but Erin Lewis won the part to everyone’s surprise and Sienna had to settle for being her understudy.

As I watch her move about the stage, my mind goes back to the tribunal hearing and Liam Baker. There are little pictures and big pictures at play. The little everyday picture is that Sienna is my daughter’s best friend. The big picture is that her older sister is Zoe Hegarty, the girl in the wheelchair, who could once stand and dance and run, until Liam Baker’s “moment of madness,” which had been coming all his life.

The music stops and Mr. Ellis, the drama teacher, vaults onto the stage, repositioning some of the dancers. Dressed in trainers and faded jeans, he’s handsome in a geekish sort of way. A fringe of dark brown hair falls across his eyes and he casually brushes it away.

The scene starts again—an argument between the play’s hero and heroine. Millie plans to marry her boss even though it’s obvious Jimmy loves her. The quarrel escalates and Jimmy grabs her, planting a clumsy kiss.

Erin pushes him away angrily, wiping her mouth. “I said no tongue.”

There are whistles and catcalls from backstage and the boy bows theatrically, milking the laughter.

Mr. Ellis leaps onto the stage again, annoyed at yet another interruption. He snaps at Sienna. “What are you grinning at?”

“Sorry, sir.”

“How many times have I told you to come in on the third bar? You’re half a step behind everyone else. If you can’t get this right, I’ll put you at the back. Permanently.”

Sienna bows her head glumly.

The drama teacher claps his hands. “OK, let’s do that scene again. I’ll play your part, Lockwood. It’s a kiss, OK? I’m not asking you to take out her tonsils.”

Mr. Ellis takes his place opposite Erin, who is tall for her age and wearing flat shoes. The scene begins with an argument and ends when he puts a single finger beneath her chin and tilts her face towards his, whispering in a voice that penetrates even at the lowest volume. Erin’s hands are by her sides. Trembling slightly, her lips part and she topples fractionally forward as if surrendering. For a moment I think he’s going to kiss her, but he pulls away abruptly, breaking contact. Erin looks like a disappointed child.

“OK, that’s it for today,” says Mr. Ellis. “We’ll have another rehearsal on Friday afternoon and a full dress rehearsal next Wednesday. Nobody be late.”

He looks pointedly at Sienna. “And I expect everything to be perfect.”

The cast wander offstage and the band begins packing away instruments. Easing open a fire door, I circle a side path to the main doors of the hall where a dozen parents are waiting, some with younger children clinging to their hands or playing tag on the grass.

A woman’s voice behind me: “Professor O’Loughlin?”

I turn. She smiles. It takes me a moment to remember her name. Annie Robinson, the school counselor.

“Call me Joe.”

“We haven’t seen you for a while.”

“No. I guess my wife does most of this.” I motion to the school buildings, or maybe I’m pointing to my life in general.

Miss Robinson looks different. Her clothes are tighter and her skirt shorter. Normally she seems so shy and distracted, but now she’s more focused, standing close as if she wants to share a secret with me. She’s wearing high heels and her liquid brown eyes are level with my lips.

“It must be difficult—the breakup.”

I clear my throat and mumble yes.

Her extra-white teeth are framed by bright painted lips.

Dropping her voice to a whisper, “If you ever need somebody to talk to… I know what it’s like.” She smiles and her fingers find my hand. Intense embarrassment prickles beneath my scalp.

“That’s very kind. Thank you.”

I muster a nervous smile. At least I hope I’m smiling. That’s one of the problems with my “condition.” I can never be sure what face I’m showing the world—the genial O’Loughlin smile or the blank Parkinson’s mask.

“Well, it’s good to see you again,” says Miss Robinson.

“You too, you’re looking…”

“What?”

“Good.”

She laughs with her eyes. “I’ll take that as a compliment.”

Then she leans forward and pecks me on the lips, withdrawing her hand from mine. She has pressed a small piece of paper into my palm, her phone number. At that moment I spy Charlie in the shadows of the stage door, carrying a schoolbag over her right shoulder. Her dark hair is still pinned up and there are traces of stage makeup around her eyes.

“Were you kissing a teacher?”

“No.”

“I saw you.”

“She kissed me…”

“Not from where I was standing.”

“It was a peck.”

“On the lips.”

“She was being friendly.”

Charlie isn’t happy with the answer. She’s not happy with a lot of things I do and say these days. If I ask a question, I’m interrogating her. If I make an observation, I’m being judgmental. My comments are criticisms and our conversations are “arguments.”

This is supposed to be my territory—human behavior—but I seem to have a blind spot when it comes to understanding my eldest daughter, who doesn’t necessarily say what she means. For instance, when Charlie says I shouldn’t bother coming to something, really she wants me to be there. And when she says, “Are you coming?” it means “Be there, or else!”

I take her bag. “The musical is great. You were brilliant.”

“Did you sneak inside?”

“Just for the second half.”

“Now you won’t come to the opening night. You’ll know the ending.”

“It’s a musical—everyone knows the ending.”

Charlie pouts and looks over her shoulder, her ponytail swinging dismissively.

“Can we give Sienna a lift home?” she asks.

“Sure. Where is she?”

“Mr. Ellis wanted to see her.”

“Is she in trouble?”

Charlie rolls her eyes. “She’s always in trouble.”

Across the grounds, down the gentle slope, I can see headlights nudging from the parking area.

Sienna emerges from the hall. Slender and pale, almost whiter than white, she’s wearing her school uniform with her hair pulled back in a ponytail. She hasn’t bothered removing her stage makeup and her eyes look impossibly large.

“How are you, Sienna?”

“I’m fine, Mr. O. Did you bring your dog?”

“No.”

“How is he?”

“Still dumb.”

“I thought Labradors were supposed to be intelligent.”

“Not my one.”

“Maybe he’s intelligent but not obedient.”

“Maybe.”

Sienna surveys the car park, as though looking for someone. She seems preoccupied or perhaps she’s upset about the rehearsal. Then she remembers and turns to me.

“Did that hearing happen today?”

“Yes.”

“Are they going to let him out?”

“Not yet.”

Satisfied, she turns and walks ahead of me, bumping shoulders with Charlie, speaking in a strange language that I’m not supposed to understand.

Although slightly taller, Charlie seems younger or less worldly than Sienna, who loves to make big entrances and create big reactions, shocking people and then reacting with coyness as if to say, “Who, me?”

Charlie is a different creature around her—more talkative, animated, happy—but there are times when I wish she’d chosen a different best friend. Twelve months ago they were picked up for shoplifting at an off-license in Bath. They stole cans of cider and a six-pack of Breezers. Charlie was supposed to be sleeping over at Sienna’s house that night but they were going to sneak out to a party. They were thirteen. I wanted to ground Charlie until she was twenty-one, but her remorse seemed genuine.

The girls have reached my third-hand Volvo estate, which reeks of wet dog and has a rear window that won’t close completely. The floor is littered with coloring books, plastic bracelets, doll’s clothes and empty crisp packets.

Sienna claims the front passenger seat.

“Sit with me in the back,” begs Charlie.

“Next time, loser.”

Charlie looks at me as though I’m to blame.

“Maybe both of you should sit in the back,” I say.

Sienna wrinkles her nose at me and shrugs dismissively but does as I ask. I can hear a mobile ringing. It’s coming from her schoolbag. She answers, frowns, whispers. The metallic-sounding voice leaks into the stillness.

“You said ten minutes. No… OK… fifteen…”

She ends the call.

“I don’t need a lift anymore. My boyfriend is picking me up.”

“Your boyfriend?”

“You can drop me at Fullerton Road shops.”

“I think you should ask your mother first.”

Sienna rolls her eyes and punches in a new number on her phone. I can only hear one side of the conversation.

“Hi, Mum, I’m going to see Danny… OK… He’ll drop me back. I won’t be late. I will… yes… no… OK… see you in the morning.”

Sienna flips the mobile shut and begins rooting in her bag, pulling out her flapper dress, which is short, beaded and sparkling.

“Eyes on the road, Mr. O, I’m getting changed.”

I tilt the rearview mirror so I can’t see behind me as I pull out of the parking area. Clothes are discarded, hips lifted and tights rolled down. By the time I reach the shops, Sienna is dressed and retouching her makeup.

“How do I look?” she asks Charlie.

“Great.”

“Where is he taking you?” I ask.

“We’re going to hang.”

“What does that mean?”

“Hang, you know. Chill.”

Sienna leans between the seats and adjusts the mirror, checking her mascara. As she pushes the mirror back in place her eyes meet mine. Did I have a girlfriend at fourteen? I can’t remember. I probably wanted one.

We’ve reached Fullerton Road. I pull up behind a battered Peugeot with two different paint-jobs and an engine that rumbles through a broken muffler. Three young men are inside. One of them emerges. Sienna is out the door, skipping into his arms. Kisses his lips. Her low-waisted dress is fringed with tassels that sway back and forth with the swing of her hips.

It looks wrong. It feels wrong.

As the car pulls away and does a U-turn, Sienna waves. I don’t respond. I’m looking in the rearview mirror unsuccessfully trying to read the number plate.

Julianne answers the door dressed in jeans and a checked shirt. Her dark hair is cut short in a new style, which makes her look younger. Sweet. Sexy. Her loose shirt shows hollows above her collarbones and the outline of her bra beneath.

She kisses Charlie’s cheek. It’s practiced. Intimate. They are almost the same height. Another two inches and they’ll see eye to eye.

“What took you so long?”

“We stopped for pizza,” answers Charlie.

“But I’ve kept your dinner!”

Julia

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...