- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

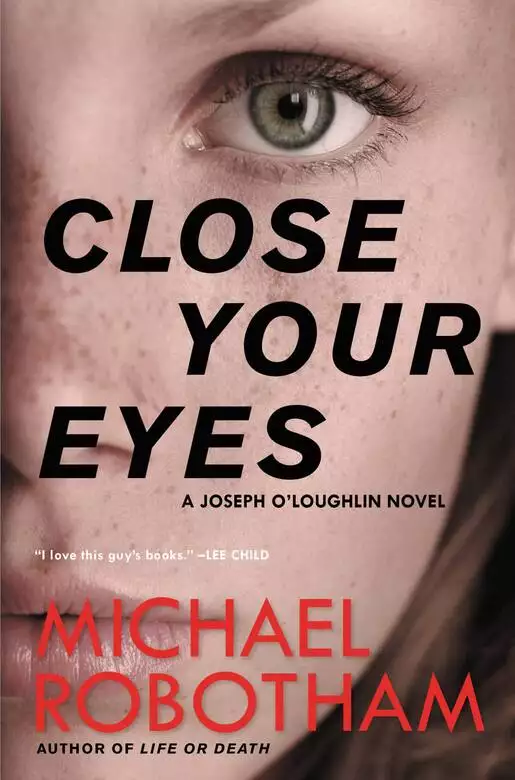

Synopsis

When a former student bungles a murder investigation, clinical psychologist Joseph O’Loughlin steps in to face a ruthless killer.

A mother and her teenage daughter are found murdered in a remote farmhouse, one defiled by multiple stab wounds and the other posed like Sleeping Beauty waiting for her prince. Joe O’Loughlin is drawn into the investigation when a former student, trading on Joe’s reputation by calling himself the “Mindhunter,” jeopardizes the police inquiry by leaking details to the media and stirring up public anger.

With no shortage of suspects and tempers beginning to fray, Joe discovers a link between these murders and a series of brutal attacks where the men and women are choked unconscious and the letter “A” is carved into their foreheads.

As the case becomes ever more complex, nothing is quite what it seems and soon Joe’s fate, and that of those closest to him, become intertwined with a merciless, unpredictable killer.

Release date: April 12, 2016

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close Your Eyes

Michael Robotham

My mother died with her head in another man’s lap. The car collided head-on with a milk tanker, which in turn crashed into an oak tree, sending acorns pinging and bouncing off the bodywork like hailstones. Mr. Shearer lost an appendage. I lost my mother. Fate laughs at probabilities.

The car was a bright red Fiesta that my mother called her “sexy little beast.” She bought it second-hand and had it resprayed at some back-street cutting shop my father knew about. I watched her leave that day. I stood at the upstairs window as she reversed out of the driveway and drove past the Tinklers’ house and Mrs. Evans who was pruning her rose bushes and Millicent Jackson who lives on the corner with her twelve cats. I didn’t realize that my world was coming apart until later. It was as though she had taken hold of a loose thread and the further she drove away from me the more the thread unraveled like a cheap sweater, first the sleeve, then the shoulder, then the front and back until I was standing naked at the window.

My Aunt Kate told me what happened—not the whole story, of course—nobody tells a seven-year-old that his mother died with a penis in her mouth. Those details tend to be glossed over like plot holes in a shitty movie or questions about how Santa Claus squeezes down all those chimneys in a single night. Everybody at my school knew before I did (about my mother, not Santa Claus). Some of the older boys couldn’t wait to tell me, while the girls giggled behind their hands.

My father said nothing, not that first day or the next or any of the subsequent ones. Instead he sat in his armchair, mouthing words as though conducting some unfinished argument. One day I asked him if Mum was in Heaven.

“No.”

“Where is she?”

“Rotting in Hell.”

“But Hell is for bad people.”

“It’s what she deserves.”

I had always assumed that Mr. Shearer also went to Hell, but discovered later that he survived the crash. I don’t know if they reattached his penis. I don’t expect they cremated it with my mother. Maybe they had to make him a prosthetic one—a bionic penis—but that sounds like something from a cheap porno.

Details like this have stayed with me while most of my other childhood memories disappeared into the long grass. My mother’s final day, in particular, is fixed in my mind, flickering against my closed eyelids, light and dark, playing on a continuous loop like an old home movie. I have protected and preserved these scenes because so little remained of my mother after my father had finished expunging her from his life and mine.

I cling to them still, these fragments of my childhood, some real, others imagined, polished like gems and as tangible and definite to me as the world I walk through now, as solid as the trees and as cool as the sea breeze. I stand on the brow of a hill and look at the spired town, shimmering beneath shades of darkening blue. Thin wisps of cloud are like chalk marks on the cold upper air. Beyond the rooftops, past the headlands and rocky beaches and sandstone cliffs, I can make out the distant shore where fallen boulders resemble sculptures, carved and smoothed by the weather.

I am not a fast walker. I take my time, stopping and pointing out things. Sheep. Cows. Birds. Horses. I make the sounds. Sheep are such passive, apathetic creatures, don’t you think? There is no intelligence in their eyes—not like dogs or horses. Sheep are just blobs of wool, blindly obedient, ignorant, as gullible as lemmings.

The footpath reaches a blind bend, hidden by the trees. This is a good place to wait. I sit with my back braced against a trunk and take an apple from my pocket, along with a blade.

“Would you like a piece?” I ask. “No? Suit yourself. You keep walking.”

I don’t mind waiting. Patience is not an absence of action—it is about timing. We wait to be born, we wait to grow up and we wait to grow old…Some days, most days, I go home disappointed, but not unhappy. There will always be other opportunities. I have the patience of a fisherman. I have the patience of Job. I know all about the saints, how Satan destroyed Job’s family and his livestock and turned him from a rich man to a childless pauper overnight, yet Job refused to condemn God for his suffering.

The breeze moves through the branches of the trees and I can smell the salt and the seaweed drying on the shingle. A sharper gust of wind blows leaves against my legs and somewhere above me a dove coos monotonously. Then a dog barks, setting off a conversation with others, back and forth, bantering or grandstanding.

I get up and put on my mask. I slip my hand into my trousers and cup my scrotum. My penis doesn’t seem to belong to me. It looks incongruous, like a strange worm that doesn’t know if it wants to be a tail or a talisman.

Withdrawing my hand, I sniff my fingers and lean against the tree, watching the path. This is the right place. This is where I want to be. She will be along soon, if not today then perhaps tomorrow.

My father liked to fish. He had so little patience with most things in life, yet could spend hours staring at the tip of his rod or the float bobbing on the surface of the water, humming to himself.

“Thou shall have a fishy on a little dishy,

Thou shall have a fishy when the boat comes in.”

1

You can’t lie on the grass,” says a voice.

“Pardon?”

“You’re on the grass.”

A figure stands over me, blocking the sun. I can only see his outline until he moves his head and then I’m blinded by the glare.

“I didn’t see a sign,” I say, shielding my eyes, my hand glowing pinkly around the edges.

“Someone stole it,” says the university porter, who is wearing a bowler hat, blue blazer, and the requisite college tie. He’s in his sixties with gray hair trimmed everywhere except his eyebrows, which resemble twin caterpillars chasing each other across his forehead.

“I didn’t think Oxford suffered petty crime,” I say.

“Student high jinks,” explains the porter. “Some of ’em are too bloody clever for their own good, if you’ll pardon my language, sir.”

He offers his hand and helps me to stand. As if by magic, he produces a lint roller from his coat pocket and runs it over my shoulders and the back of my shirt, collecting the grass clippings. He takes my sports jacket and holds it open. I feel as though I’m Bertie Wooster being dressed by Jeeves.

“Were you a gownie, sir?”

“No. I went to university in London.”

The porter nods. “It was Durham for me. More an open prison than a place of higher learning.”

I find it hard to imagine this man ever being a student. No, that’s not true. I can picture him as an overbearing prefect at some minor boarding school in Hertfordshire in the 1960s, where he had an unfortunate nickname like Fishy Rowe or Crappy Cox.

“Why can’t people lie on the grass?” I ask. “It’s a lovely day—the sun is shining, the birds are singing.”

“Tradition,” he says, as though this should explain everything. “No walking on the grass, no sitting on the grass, no dancing on the grass.”

“Or the Empire will crumble.”

“Bit late for that,” he admits. “Are you sure we haven’t met, sir? I’m pretty good with faces.”

“Positive.”

He snaps his fingers exultantly. “You’re that psychologist. I’ve seen you on the news.” He’s wagging his finger now. “Professor Joseph O’Loughlin, isn’t it? You helped find that missing girl. What was her name? Don’t tell me. It’s on the tip of…the tip of…Piper, that’s it. Piper Hadley.” He beams as though waiting to be congratulated. “What brings you here? Are you going to be lecturing?”

“No.”

I glance across the college lawn where colored flags flutter above the entrances and balloons hang from windows. The university Open Day is in full swing and students are manning tables and stalls, handing out brochures to prospective undergraduates, publicizing the various courses, clubs, and activities. There is a Real Ale Society and a Rock Music Society and a C. S. Lewis Society; and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer/Questioning Society—a mouthful whichever way you swing.

“My daughter is looking over the colleges,” I say. “She and her mother are inside.”

“Excellent,” says the porter. “Has she been offered a place?”

“I’m not sure,” I say, trying to sound informed. “I mean, I think so, or she might still take a gap year.” In truth, I have no idea. The porter frowns and his eyebrows begin to crawl, dipping and bowing above his eyes.

My body chooses that moment to freeze and I’m caught in a classic James Bond crouch, without the gun, of course, my face rigid and body locked in place like I’m a playing a game of musical statues.

“Everything all right?” asks the porter when I jerk back into motion. “You went all stiff and scary.”

“I have Parkinson’s.”

“Tough break. I have gout,” he says, as though the two conditions are somehow comparable. “My doctor says I drink too much and my eyesight is getting worse. I have trouble distinguishing between a pub sign and a house fire.”

Two teenagers are chasing each other across the grass. The porter yells at them to stop. He touches his bowler hat and wishes me the best of luck before he takes off in pursuit, swinging his arms as though doing a quick march on a parade ground.

The midday tour of the college is finishing. I look around for Charlie and Julianne among the crowds of people spilling from the doors and wandering along the paths. I hope I haven’t missed them.

There they are! Charlie is chatting to a student—a boy, who points to something over her shoulder, giving her directions. He tosses a non-existent fringe out of his eyes and types her number into his mobile phone. Another boy leans down and whispers in his ear. They’re checking my daughter out.

“She’s not even a fresher yet,” I mutter to myself.

Julianne is picking up brochures from a table. She’s wearing white linen trousers and a silk blouse, with a pair of red sunglasses perched on her head. She doesn’t look so different from when we first met almost thirty years ago—tall and dark-haired, a little more muscular, athletic although curvaceous. Estranged wives shouldn’t look this good; they should be unappealing and sexless, with belly fat and drooping breasts. I’m not being sexist. Ex-husbands should be the same—overweight, balding, going to seed…

Charlie has chosen a loose-fitting dress and Doc Martens, a combination that doesn’t come as a surprise. Mother and daughter are almost the same height, with the same full lips, thick eyelashes, and a widow’s peak on their foreheads. My daughter has the more inquisitive face and is prone to sarcasm and occasional profanities, which I can live with unless she utters them in front of Emma, her younger sister.

Eleven weeks from now, Charlie will be leaving home for university. She was interviewed for a place at Oxford last December—as well as at three other universities—and I know she received offers in January, but she hasn’t revealed which one she accepted or what she might study. Lately I have caught myself hoping that she’s flunked her A-levels exams and will have to retake them. I know that’s a terrible thing for a father to wish, although I suspect I’m not the first.

Charlie spots me and waves. She breaks into a trot like a pedigree dog at Crufts. Likening my teenage daughter to a dog is not very PC or paternal, but Charlie has many other fine canine traits, not least of them loyalty, intelligence, and sorrowful brown eyes.

Julianne puts her arm through mine. She walks slightly up on her toes, resembling a ballet dancer. Always has done.

“So what have you been up to?” she asks.

“Chatting to the locals.”

“Was that a college porter?”

“It was.”

“It’s nice to see you making friends.”

“I’m that sort of guy.”

“Normally you appraise people rather than befriend them.”

“What does that mean?”

“You remind me of a mechanic who can’t look at the car without wondering what’s under the bonnet.”

Julianne smiles and I marvel at how she can make a criticism sound remarkably similar to a compliment. I was married to this woman for twenty-two years and we’ve been separated for six. Not divorced. They say hope springs eternal, but I sense that I may have excavated that particular well and found it to be bone dry.

“So what do you think?” I ask Charlie.

“It’s like Hogwarts for grown-ups,” she replies. “They even wear gowns to dinner.”

“What about a sorting hat and floating candles?”

She rolls her eyes.

I don’t know what’s more out-of-date, Harry Potter or my jokes.

“There’s a band playing down by the river,” says Charlie. “Can I go?”

“Don’t you want to have lunch?”

“I’m not hungry.”

“We should talk about university,” I say.

“Later,” she replies.

“Have you accepted an offer?”

“Yes.”

“Where?”

She holds out her arms. “I’ll give you one guess.”

“But what are you going to study?”

“Good question.”

Charlie is teasing me. Keeping her own counsel. I will be the last to know unless fatherly advice or money is needed, when suddenly I will become the fount of all wisdom and master of the wallet.

“Where are we going to meet?” asks Julianne.

“I’ll call you,” replies Charlie, holding out her open palm toward me. I pretend to look elsewhere. Her fingers make a curling gesture. I take out my wallet and, before I can count the notes, she has plucked a twenty from my fingers and kissed me on the cheek. “Thanks, Daddy.”

She turns to Julianne. “Did you ask him?” she whispers.

“Shush.”

“Ask me what?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

They’re obviously planning something. Charlie has been particularly attentive all day, holding my hand—the left one, of course—and matching stride with me.

What is it that I’m not being told?

When I look back from Julianne, Charlie has already gone, her dress billowing in the breeze, pushed down by her hands.

It’s almost lunchtime. I need food or my medication will likely go haywire and I’ll begin twerking like Miley Cyrus.

“Where do you want to eat?” I ask.

“The pub,” says Julianne, making it sound obvious. We walk through the arched stone gate and turn along St. Aldate’s where the pavements are crowded with parents, prospective students, tourists, and shoppers. Chinese and Japanese tour groups in matching T-shirts are following brightly colored umbrellas.

“It’s all very Brideshead Revisited, isn’t it? Sometimes I wonder if it’s more a theme park than a university.”

“Has Charlie told you what she’s going to study?” I ask.

“Not a word,” says Julianne, sounding unconcerned.

“Surely there must be some rule against that. No walking on the grass—or keeping secrets from your parents.”

“She’ll tell us when she’s ready.”

Despite my reservations about her leaving home, I love the idea of Charlie going to university. I envy her the friends she’ll make and the fresh ideas she’ll hear, the discussions and debates, the subsidized alcohol, the parties, the bands and romances.

As we approach the intersection, I hear a commotion. A protest march is converging on the high street. People are chanting and carrying placards. Pedestrians have been stopped at the corner by several police officers. Someone is beating a snare drum next to a girl playing “Yankee Doodle” on a flute. A boy with pink streaks in his hair thrusts a leaflet into my hand.

“What are they protesting about?” asks Julianne.

“Starbucks.”

“For serving lousy coffee?”

“For not paying UK tax.”

Further along the street, I notice the Starbucks logo. One of the posters bobs past, reading, Too little, too latte.

“We used to march against apartheid,” I say.

“It’s a different world.”

The march moves on. They’re a harmless-looking bunch. I can’t imagine any of them blowing up parliament or piloting the tumbrils to the guillotines. Most of them are probably heirs to family fortunes or ancestral titles. They’ll be running the country in thirty years. God help us!

Julianne chooses a pub by the river, which is decorated with hanging baskets of flowers and has an outside courtyard with tables overlooking the water. There are couples punting on the river, negotiating the wilting branches of willow trees and the swifter current on the outside of each bend. A rogue balloon skitters across the rippled surface and gets caught in the reeds.

After ordering a mezze plate to share, I go to the bar and get a large glass of wine for Julianne and a soft drink for myself. We toast and clink and make small talk, which is relaxed and natural. Ever since the separation we’ve continued to communicate, phoning each other twice a week to discuss the girls. Julianne is always bright and cheerful—happier now that she’s not with me.

As exes go, she’s one of the better ones—from all reports. Maybe it would be easier if she were a harridan or a poisonous shrew. I could have put our marriage behind me and found someone else. Instead I hang on, forever hopeful of a second chance or extra time. I’d happily go to penalties if the scores are still level.

“Are you sure Charlie has a plan?” I ask.

“Did you have a plan at eighteen?”

“I wanted to sleep with lots of girls.”

“How did that work out?”

“It was going fine until you came along.”

“So I should apologize for cramping your style.”

“You dented my average.”

“You were a complete tail-ender. A number eleven batsman if ever I saw one.”

“I managed to bowl you over.”

“Now you’re mixing metaphors.”

“No, I’m not—I’m an all-rounder.”

She laughs and waves me away. It feels good to make her happy. I met Julianne at London University. I’d spent three years doing medicine despite fainting at the first sight of blood, and Julianne was a fresher in her first year studying languages. I changed direction and transferred to psychology—much to my father’s disgust. He’d expected me to become a surgeon and carry on four generations of family history. They say a chain always breaks at the weakest link.

Our food has arrived. Julianne scoops hummus on to crusty bread and chews thoughtfully. “Are you seeing anyone?” she asks, sounding nervous.

“Not really, how about you?”

She shakes her head.

“What about that lawyer? I can’t remember his name.”

“Yes, you can.”

She’s right. Marcus Bryant. Handsome, successful, painfully worthy—a suitor from central casting, if such an agency existed. I once made the mistake of looking him up on Google, but didn’t get past his four-year stint working for the International War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague and his pro-bono work with death row inmates in Texas.

There is another long silence. Julianne speaks first.

“If I had my life over again, I don’t think I would have married so young.”

“Why?”

“I wish I’d done more traveling.”

“I didn’t stop you traveling.”

“I’m not criticizing you, Joe,” she says, “I’m just making an observation.”

“What else do you wish you’d done—had more lovers?”

“That would have been nice.”

I try to share her laugh, but instead feel melancholy.

She responds, reaching across the table. “Oh, I’ve hurt you now. Don’t get sad. You were great in the sack.”

“I’m not sad. It’s the medication.”

She smiles, not believing me. “There must be something you’d change.”

“No.”

“Really?”

“Maybe one thing.”

“What?”

“I wouldn’t have slept with Elisa.”

The admission creates a sudden vacuum and Julianne withdraws her hand, half turning away. Her gaze slips across the river to a boathouse on the far bank. For the briefest of moments her eyes seem to glisten but the sheen has gone when she turns back.

Almost ten years ago, on the day I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease I didn’t go straight home. I didn’t buy a red Ferrari or book a world cruise or draw up a bucket list. Nor did I purchase a case of Glenfiddich and crawl into bed for a month. Instead I slept with a woman who wasn’t my wife. It was a stupid, stupid, stupid mistake that I have tried to rationalize ever since, but my excuses don’t measure up to the damage I caused.

A single, random, foolish event can often change a life—a chance meeting, or an accident or a moment of madness. But more often it happens by increments like a creeping tide, so slowly that we barely notice. My life was altered by a diagnosis. It was never going to be a death sentence, but it has robbed me by degrees.

“I apologize for prying,” says Julianne, toying with the stem of her wine glass.

“You’re allowed.”

“Why?”

“I guess technically we’re still married.”

She sips her wine, not responding. Silence again.

“So what are your plans for the summer?” she asks. “Going anywhere nice?”

“I haven’t decided. I might pick up one of those late package deals to Florida. Palm trees. Pouting girls. Bikinis. Surgically enhanced bodies.”

“You hate the beach.”

“Salsa. Mambo. Cuban cigars.”

“You don’t smoke and you can’t dance.”

“There you go—spoiling my fun.”

Julianne leans forward, putting her elbows on the table. “I have something important to ask you.”

“OK.”

“Perhaps I should have asked sooner. I’ve thought about it for a long time, but I guess I’m a little scared of what you might say.”

This is it! She wants a divorce. No more tiptoeing around the subject or beating around the bush. Maybe she’s going to marry Marcus and join him in America. Or she’s decided to sell the last of her father’s paintings and take a round-the-world cruise. But she hates cruises. An African safari—she’s always talked about going to Africa.

“Joe?”

“Huh?”

“Have you been listening?”

“Sorry.”

“I was telling you a story.”

“You know I love stories.”

Her eyes darken, warning me to take this seriously.

“It was in the newspaper. An old woman in Glasgow lay dead inside her house for eight years. No one came to visit. Nobody raised the alarm. Her gas and electricity were cut off. Windows were broken in a storm. Mail piled up on the floor inside. But nobody came. They found her skeleton lying next to her bed. They think she fell and broke her hip and could have lived for days before she died, crying out for help, but nobody heard her. And now her family are fighting over her house. They all want a slice of her money. Makes you wonder…”

“What about?”

“How terrible it must be to die alone.”

“We all die alone,” I say, but regret it immediately because it sounds too flippant and dismissive. It’s my turn to reach across the table and touch her hand. She raises her fingertips and our fingers interlock. “We’re not responsible for other people’s mistakes. Isn’t that what you’re always telling me?”

She nods.

“You’re a good father, Joe.”

“Thank you.”

“You’re too soft on the girls.”

“Someone has to be the good cop.”

“I’m being serious.”

“So am I.”

“You’re a kind man.”

I’ve always been a kind man. I was a kind man six years ago when you left me.

Is this leading up to some sort of apology, I wonder. Maybe she wants to give me another chance. A pearl of sweat slides from my hairline, down my spine to the small of my back.

“I know we can’t have our time over again,” says Julianne, “and we can’t make amends for all of our mistakes…”

“You’re beginning to frighten me,” I say.

“It’s nothing that dramatic,” she replies, solemn again. “What I wanted to ask is whether you’d like to spend the summer with us?”

“Pardon?”

“Emma and Charlie are willing to share, which means you’ll have a room to yourself.”

“At the cottage?”

“You said you were going to take a few weeks off. You could commute to London if you have to work. The girls really want to see more of you.”

“You want me to move back in…as a guest.”

“You’re not a guest. You’re their father.”

“And you and I…?”

Her head tilts slightly to one side. “Don’t read too much into it, Joe. I just thought it might be nice to spend the summer together.” She withdraws her hand and looks away. Breathes out. Breathes big. “I know it’s short notice. You don’t have to say yes.”

“No.”

“Oh.”

“No, I mean, I know there’s no pressure. It sounds perfect, it really does…it’s just…”

“What?”

“I guess I’m scared that if I spend so much time with the girls, it’s going to be hard to say goodbye again.”

She nods.

“And I might fall madly in love with you again.”

“Restrain yourself.”

I hope I’m smiling. A young couple at a nearby table laugh loudly. The girl’s voice is light and sweet and happy. I take a deep breath and hold it in my lungs.

Saying nothing is the wrong choice. I must make a declaration or meet her halfway. She has thrown me a lifeline. I should grab it with both hands, but I’m not sure if the lifeline is tied on to anything.

“You don’t have to let me know straight away,” she says defensively. Hurt.

“No, I think I’ll come.”

Even as I utter the statement, I can hear a small alarm pinging in my head, as though I haven’t fastened the seat belt or I’ve left my keys in the ignition. It’s not much of a plan. There are bound to be repercussions. Tears.

Julianne’s lips stretch into a wide smile, showing off her teeth, wrinkling her eyes. We continue to eat, but the conversation isn’t as easy as before, the questions or the answers.

Charlie calls and arranges to meet us. She’s not far away. Outside the pub, Julianne fishes for her car keys in her soft leather shoulder bag.

“You do understand that this is just for the summer?”

“Of course.”

“I don’t want you getting your hopes up.”

“My hopes are exactly where you want them to be.”

Julianne turns her back to me as though she’s retrieving something secret from her bag, but she’s carrying nothing when she turns. “So when would you like to come?”

“How about at the weekend?”

“Excellent,” she answers. “I guess I don’t have to give you directions.”

“No.”

She pauses. “Do you feel all right, Joe?”

“I do.”

“There are lots of things we haven’t talked about.”

“True.”

“Maybe we will.”

She leans closer to kiss me. I am tempted to go for the lips, but she turns her cheek and I make do with the warm, soap-scented smell of her and the weight of her head when it rests for a moment on my shoulder.

Take heart, I tell myself, as she slips on her sunglasses.

My phone is vibrating. I fish it out of my pocket and glance at the screen. Veronica Cray is calling me. I put the phone away.

“You should get that,” says Julianne.

“It can wait.”

My phone vibrates again. Same caller ID. It won’t be good news. It never is when it comes from a detective chief superintendent in charge of a serious crime squad. She won’t be calling to say I’ve inherited a fortune or picked a six-horse accumulator or won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Julianne is watching me. Waiting. I smile at her apologetically and hold up a finger, mouthing the words “one minute.”

“Chief Superintendent.”

“Professor.”

“Can I call you back?”

“No.”

“It’s just that I’m—”

“Busy, yeah, I know, so am I. I’m busier than a one-legged Riverdancer and you won’t call me back because you don’t want to talk to me. You never do because you think I want something. But just stop for a moment and consider that this could be a social call. I might be calling as a friend. I might want to chew the fat.”

“Are you calling as a friend?”

“Of course.”

“So you want to chew the fat?”

“Absolutely, but since we’ve run out of things to talk about, I want you to look at something for me.”

“I’ve retired from profiling.”

“I’m not asking for a profile. I want your opinion.”

“On a crime?”

“Yes.”

“A murder.”

“Two of them.”

I wait, picturing the detective, who is built like a barrel with spiky, short-cropped hair and a penchant for wearing men’s shoes. She spells her surname with a “C” not a “K” because she doesn’t want anyone to know that she’s related to a pair of psychotic brothers, twins who terrorized London’s East End in the sixties.

I’ve known Ronnie Cray for almost seven years, ever since she watched me vomit by a roadside after a naked woman jumped to her death from the Clifton Suspension Bridge. I was supposed to talk the woman down. I failed. The events that followed cost me my marriage. Ronnie Cray was in charge of that investigation. I think she blames herself for not protecting my family, but it was nobody’s fault except mine. Since then the DCS has stayed in touch, sometimes asking for my advice on a particular case or dropping details like breadcrumbs, hoping that I might follow the trail. Now she’s a friend, although I’m never quite sure when to call someone a friend. I have so few of them.

“Find another psychologist,” I tell her.

“I did. He calls himself ‘the Mindhunter.’ Advertises his services. You must have heard of him.”

“No.”

“That’s odd. He says you taught him everything he knows.”

“What!”

. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...