- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

During the worst blizzard in decades, a husband and wife are brutally killed in their home while half of London is without power. The suspect, a troubled young man who reported the killings, is in custody, unable or unwilling to explain his presence in the couple's home. Joe O’Loughlin is certain the young man is hiding something—but with murders this methodical, and a suspect who exhibits the signs of developing schizophrenia, the young man seems anything but responsible. But if the suspect isn’t the killer, who is? And what do the murders have to do with the disappearance of the teenaged girl who once inhabited the very same room where the murders took place?

Release date: October 2, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

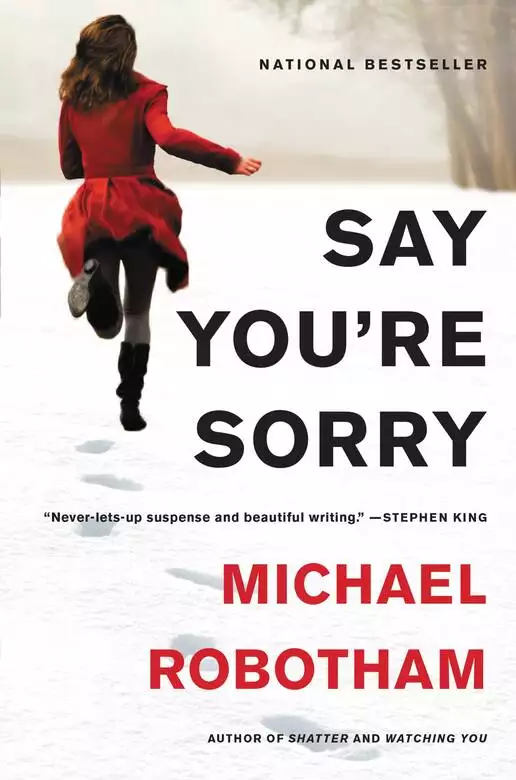

Say You're Sorry

Michael Robotham

I went missing on the last Saturday of the summer holidays three years ago. I didn’t disappear completely and I didn’t run away, which is what a lot of people thought (those who didn’t believe I was dead). And despite what you may have heard or read, I didn’t get into a stranger’s car or run off with some sleazy pedo I met online. I wasn’t sold to Egyptian slave traders or forced to become a prostitute by a gang of Albanians or trafficked to Asia on a luxury yacht.

I’ve been here all along—not in Heaven or in Hell or that place in between whose name I can never remember because I didn’t pay attention at Sunday scripture classes. (I only went for the cake and the cordial.)

I’m not exactly sure of how many days or weeks or months I’ve been here. I tried to keep count, but I’m not very good with numbers. Completely crap, to be honest. You can ask Mr. Monroe, my old math teacher, who said he lost his hair teaching me algebra. That’s bollocks by the way. He was balder than a turtle on chemo before he ever taught me.

Anyone who follows the news will know that I didn’t disappear alone. My best friend Tash was with me. I wish she were here now. I wish she’d never squeezed through the window. I wish I had gone in her place.

When you read those stories about kids who go missing, they are always greatly loved and their parents want them back, whether it’s true or not. I’m not saying that we weren’t loved or missed, but that’s not the whole story.

Kids who blitz their exams don’t run away. Winners of beauty pageants don’t run away. Girls who date hot guys don’t run away. They’ve got a reason to stay. But what about the kids who are bullied or borderline anorexic or self-conscious about their bodies or sick of their parents fighting? There are lots of factors that might push a kid to run away and none of them are about being loved or wanted.

I don’t want to think about Tash because I know it’s going to make me upset. My handwriting is messy at the best of times, which is weird when you consider I won a handwriting competition when I was nine and they gave me a fountain pen in a fancy box that bit my finger every time I closed it.

We disappeared together, Tash and me. That was a summer of hot winds and fierce storms that came and went like, well, storms do. It was on a clear night at the end of August after the Bingham Summer Festival, when the funfair rides had fallen silent and the colored lights had been turned off.

They didn’t realize we were gone until the next morning. At first it was just our families who searched, then neighbors and friends, calling our names across playgrounds, down streets, over hedges and across the fields. As the hours mounted they phoned the police and a proper search was organized. Hundreds of people gathered on the cricket field, dividing up into teams to search the farms, forests and along the river.

By the second day there were five hundred people, police helicopters, sniffer dogs and soldiers from RAF Brize Norton. Then came the journalists with their satellite dishes and broadcast vans, parking on Bingham Green and paying locals to use their toilets. They did their reports from in front of the town clock, telling people there was nothing to report, but saying it anyway. This went on for days on every channel, every hour, because the public wanted to be kept up-to-date on the nothingness.

They called us “the Bingham Girls” and people made shrines of flowers and tied yellow ribbons to lampposts. There were balloons and soft toys and candles just like when Princess Diana died. Complete strangers were praying for us, weeping as though we belonged to them, as though we summed up the tragedies in their own lives.

We were like fairy-tale twins, like Hansel and Gretel or the babes in the wood, or the Soham girls in their matching Man United shirts. I remember the Soham girls because our school sent cards to their families saying our prayers were with them.

I don’t like those old fairy tales—the ones about children getting eaten by wolves or kidnapped by witches. At our primary school they took Hansel and Gretel off the shelves because some of the parents complained it was too scary for children. My dad called them PC Nazis and said next time they’d be saying Humpty Dumpty promoted violence against unborn chickens.

My dad isn’t famous for his sense of humor, but he does have his moments. He once made me laugh so hard I snorted tea out my nose.

As the days passed, the media storm blew through Bingham. Cameras came into our houses, up the stairs, into our bedrooms. My bra was hanging off the doorknob and there was an empty tampon box on my bedside table. They called it a typical teenager’s room because of the posters and my collection of crystals and my photo-booth portraits of my friends.

My mum would normally have gone mental about the house being so messy, but she mustn’t have felt much like cleaning up. She didn’t feel much like breathing by the look of her. Dad did most of the talking, but still came across as a man of few words, the strong silent type.

Our parents picked apart our last days, putting them together from fragments of information like those scrapbooks people make about their newborn babies. Every detail seemed important. What book I was reading: Curious Incident—for the sixth time. What DVD I last borrowed: Shaun of the Dead. If I had a boyfriend: Yeah, right!

Everyone had a story about us—even the people who never liked us. We were cheeky, fun-loving, popular, hard-working; we were straight-A students. I laughed my ass off at that one.

People put a shine on us that wasn’t there for real, making us into the angels they wanted us to be. Our mothers were decent. Our fathers were blameless. Perfect parents who didn’t deserve to be tormented like this.

Tash was the bright one and the pretty one. She knew it too. Always wearing short skirts and tight tops. Even in her school uniform she was striking, with breasts like hood ornaments that announced her arrival. They belonged to a grown woman, a lucky woman, a woman who could model bras or be draped over the bonnet of a sports car at a motor show. She lapped up the attention, rolling the waistband of her skirt to make it shorter, undoing the top button of her blouse.

At fifteen a girl’s looks are pretty fickle. Some blossom and others play the clarinet. I was skinny with freckles, a big old head of tangly black hair, a pointy chin and the eyelashes of a llama. My assets hadn’t arrived, or they’d been delivered to someone who must have prayed harder, or prayed at all.

I was built for speed rather than low-cut dresses and short skirts. Rake-thin, a runner, I was second in the nationals for my age group. My father said I was part-whippet, until I pointed out that likening me to a dog did nothing for my self-esteem. Homely, was my grandmother’s description. Bookish, said my mother. They could have said plain as a pikestaff, but I don’t know what a pikestaff looks like. Maybe I make a pikestaff look good.

Tash was an ugly duckling that blossomed into a swan, while I was the duckling who grew into a duck—a less happy ending, I know, but more realistic. Put another way, if I was an actress in a horror movie, you’d take one look at me and say, “She’s toast.” Whereas Tash would be the girl who gets her kit off in the shower and is rescued in the nick of time and lives happily ever after with the hero and his perfect teeth.

Maybe she deserved that happy ending, because real life hadn’t been such a picnic. Tash grew up in an old farmhouse half a mile from Bingham, along a narrow lane that is just wide enough for single cars or tractors. Mr. McBain rented the farm, hoping to buy it, but he could never raise the money.

I remember my mother saying the McBains were white trash, something I never really understood. A lot of people rent houses and send their kids to public schools, but that doesn’t make them any more fucked up than the rich people living in Priory Corner.

That’s where I used to live, in a house called The Old Vicarage. It used to house the vicar until the church decided it needed even more money and sold off the house and land. The streets of Priory Corner aren’t paved with gold, but our neighbors act as though they should be.

Like everyone else in town, they put up posters in their windows and stickers on their cars after we disappeared. There were candlelight vigils and special masses at St. Mark’s and prayers at school. So many prayers, I wonder how God missed hearing any of them.

You’re probably wondering how I know this stuff about the police search and the vigil. During those first few weeks George let us watch TV and read the newspapers. We were chained up in an attic room with sloping ceilings and a skylight that was stained with birdshit. The room was airless and hot beneath the tiles, but still much nicer than this place. There was a proper bed and an old TV with a coat hanger aerial and a blizzard of static on most channels.

On the third day, I saw Mum and Dad on the screen, looking like rabbits caught in a high beam. Mum wore her black pencil dress by Alexander McQueen and a dark pair of half-pumps. Tash knew the brand. I’m not very good with designer clothes. Mum was clutching a photograph. She’d found her voice and they couldn’t stop her talking.

She listed all the clothes I might have been wearing, as though I might have dropped them like breadcrumbs, leaving a trail for people to follow. Then she paused and stared at the TV cameras. A tear hovered halfway down her cheek and everyone waited for it to fall, not listening to what she said.

Mr. and Mrs. McBain were also at the news conference. Mrs. McBain hadn’t bothered about make-up… or sleeping. She had bags under her eyes and was wearing a T-shirt and an old pair of jeans.

“Like something the cat dragged in,” said Tash.

“She’s worried about you.”

“She always looks like that.”

My dad took a shaky breath, but the words came out clearly.

“Somebody out there must have seen Piper and Tash. Maybe you’re not sure or you’re protecting someone. Please think again and call the police. You can’t imagine what Piper means to us. We’re a strong family and we don’t survive well apart.”

He looked directly into the cameras. “If you took our babies, please just bring them home. Drop them off at the end of the road or leave them somewhere. They can catch a bus or a train. Let them walk away.”

Then he spoke to Tash and me.

“Piper, if you and Tash are watching. We’re coming to find you. Just hold on. We’re coming.”

Mum had panda eyes from her mascara running but still looked like a film star. Nobody poses for a photograph like she does.

“Whoever you are—we forgive you. Just send Piper and Tash home.”

My sister Phoebe was put in front of the cameras wearing her prettiest dress, standing pigeon-toed, sucking on her fingers. Mum had to prompt her.

“Come home, Piper,” she said. “We all miss you.”

Tash’s father had his arms crossed through the whole circus. He didn’t say a word until at the very end when a reporter asked, “Haven’t you got anything to say, Mr. McBain?”

He gave the reporter a death stare and unfolded his arms. Then he said, “If you still have them, let them go. If they’re dead, tell somebody where you left them.”

He folded his arms again. That was it. Two sentences.

Something tore inside Tash’s mum and she made this small, frightened animal sound, like a kitten squeaking in a box.

There were rumors about Mr. McBain after that. People asked, “Where was his emotion? Why did he suggest they were dead?”

Apparently, you’re supposed to quiver and blubber at news conferences. It’s like some unwritten law, otherwise people will think you’ve raped and murdered your daughter and her best friend.

At the end of the questions, my mother held up a photograph of Tash and me. It’s the picture that became famous, the one everyone remembers, taken by Mr. Quirk, our school photographer (he of the wandering hands and minty breath, notorious for straightening collars, brushing skirts and feeling boobs).

In the photograph Tash and I are sitting together in the front row of our class. Tash’s skirt is so short she has to keep her knees together and her hands on her lap to avoid flashing the camera. Flashing the flash, so to speak. I’m next to her with a mop of hair and a fake smile that would make Victoria Beckham proud.

That’s the photograph everybody remembers: two girls in school uniform, Piper and Tash, the Bingham Girls.

No matter what channel you switched on, you could see us, or hear our parents pleading for information. Millions of words were written in the newspapers, page after page about new developments, which weren’t really new and added up to nothing.

At the candlelight vigil Reverend Trevor led the prayers while his wife Felicity led the gossiping. She’s like a human megaphone with a huge arse and reminds me of those dippy birds that rock back and forth, putting their beaks into a glass.

She and the reverend have a son called Damian who should have a cross carved in his forehead because he belongs to the dark side. The little shit likes to creep up behind girls and flick their bra straps. He never did it to me because I’m quicker than he is and I once shoved his asthma inhaler up his nose.

There was standing room only at St. Mark’s for the vigil. They had to put loud speakers outside so people could hear the prayers and the hymns. The only thing missing were the children. Parents were so terrified of more kidnappings that they kept their little ones at home behind locked doors, safely tucked away.

That was the weekend that the grief tourists began arriving. People drove from Oxford and beyond, circling the streets. They went to the church and stared at our school and at The Old Vicarage.

They watched the reporters talking breathlessly to cameras, making nothing into something, picking the scabs off past tragedies, tossing out names like Holly Wells, Jessica Chapman and Sarah Payne, filling a few more hours with rumor and speculation.

Afterwards the tourists drove away looking slightly disappointed. They wanted Bingham to be more sinister, a place where teenagers disappeared and didn’t come home.

It’s freezing outside—minus twenty-six degrees in places—extraordinary for this time of year. I felt like Scott of Antarctica when I walked to work this morning across Hyde Park—O’Loughlin of the Serpentine, battling the extremes—although I looked more like a bloated contestant on Dancing on Ice.

The snow began falling four days ago, big wet flakes that melted, refroze and were covered again, stupefying traffic and silencing roads. There aren’t enough snowplows to clear motorways or council trucks to grit the streets. More grit has been needed, literally and figuratively.

Airports have been shut. Flights grounded. Vehicles abandoned. Tens of thousands of people are stranded at terminals and motorway service stations, which look like refugee camps full of the displaced and dispossessed, huddling beneath thermal blankets in a sea of silver foil.

According to the TV weather reports, a dense block of cold air is sitting over Greenland and Iceland, blocking the jet stream from the Atlantic. At the same time winds from the Arctic and Siberia have “turbo-charged” the cold because of something called an Arctic Oscillation.

Normally, I don’t mind the snow. It can hide a lot of sins. London looks beautiful under laundered sheets, like a city from a fairy tale or a sound studio. But today I need the trains to be running on time. Charlie is coming up to London and we’re going to spend four days together in Oxford. This is a father–daughter bonding weekend although she would probably call it something else.

A boy is involved. His name is Jacob.

“Couldn’t you find an Edward?” I asked Charlie. She gave me a look—the one she learned from her mother.

I don’t know much about Jacob other than his brand of underwear, which he advertises below his arse crack. He could be very nice. He may have a vocabulary. I do know that he’s five years older than Charlie, and that they were caught together in her bedroom with the door closed. Kissing, they said, although Charlie’s blouse was unbuttoned.

“You have to talk to her,” Julianne told me, “but do it gently. We don’t want to give her a complex.”

“What sort of complex could we give her?” I asked.

“We could turn her off sex.”

“That sounds like a bonus.”

Julianne didn’t find this funny. She has visions of Charlie succumbing to low self-esteem, which apparently is the first step on the slippery slope to eating disorders, rotten teeth, a bad complexion, tumbling grades, drug addiction and prostitution. I’m exaggerating of course, but at least Julianne turns to me for advice.

We’re estranged, not divorced. The subject is raised occasionally (never by me) but we haven’t got round to signing the papers. In the meantime, we share the raising of two daughters, one of them a bright, enchanting seven-year-old, the other a teenager with a smart mouth and a dozen different moods.

I moved back to London eight months ago. Sadly, I don’t see as much of the girls, which is a shame. I have almost come full circle—establishing a new clinical practice and living in north London. This is how it used to be five years ago when Julianne and I had a house on the border of Camden Town and Primrose Hill. In the summer, when the windows were open, we could hear the sound of lions and hyenas at London Zoo. It was like being on safari without the minivans.

Now I live in a one-bedroom flat that reminds me of something I had when I was at college—cheap, transitory, full of mismatched furniture and a fridge stocked with Indian pickles and chutneys.

I try not to dwell on the past. I touch it only gingerly with the barest tips of my thoughts, as though it were a worrying lump in my testis, probably benign, but lethal until proven otherwise.

I am practicing again. There is a bronze plaque on the door saying JOSEPH O’LOUGHLIN, CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST, with various letters after my name. Most of my referrals are from the Crown Prosecution Service, although I work two days a week for the NHS.

So far today I have seen a cross-dressing car salesman, an obsessive-compulsive florist and a nightclub bouncer with anger management issues. None of them are particularly dangerous, simply struggling to cope.

My secretary, Bronwyn, knocks on the door. She’s an agency temp who chews gum faster than she types.

“Your two-o’clock is here,” she says. “I was wondering if I could leave early today?”

“You left early yesterday.”

“Yes.”

She departs without further discussion.

Mandy enters, aged twenty-nine, blonde and overweight, with terrible skin and eyes that should belong to an older woman. She has been sent to see me because her two children were found alone in a locked flat in Hackney. Mandy had gone clubbing with her boyfriend and slept over at his place. She told police that she felt her daughter, aged six, was old enough to look after her younger brother, four. Both children are fine, by the way. A neighbor found them fluttering like chickens over the biscuit crumbs and feces that dotted the carpet.

Mandy looks at me accusingly now, as though I’m personally responsible for her children being taken into care. For the next fifty minutes we discuss her history and I listen to her excuses. We agree to meet next week and I write up my notes.

It’s just after three. Charlie’s train arrives in half an hour and I’m going to meet her at the station. I don’t know what we’ll do in Oxford on the weekend. I’m due to talk at a mental health symposium, although I can’t imagine anyone showing up, given the weather, but the tickets have been sent (first class) and they’ve booked me into a nice hotel.

Packing my briefcase, I take my overnight bag from the cupboard and lock up the office. Bronwyn has already gone, leaving a hint of her perfume and a lump of chewing gum stuck to her mug.

At Paddington Station I look for Charlie among crowds of passengers spilling from the carriages of the First Great Western service. She’s among the last off the train. She’s talking to a boy who is pushing a mountain bike with all the nonchalance of a Ferrari driver. He’s wearing a duffel coat and is cultivating sideburns.

The boy rides away. Charlie restores a set of white earbuds to her ears. She’s wearing jeans, a baggy sweater and an overcoat left over from the German Luftwaffe.

She offers me each cheek to kiss and then leans into a hug.

“Who was that?”

“Just a guy.”

“Where did you meet him?”

“On the train.”

“What was his name?”

She stops me. “Is this going to be twenty questions, Dad, because I didn’t take notes. Was I supposed to take notes? You should have warned me. I could have written you a full report.”

The sarcasm she inherited from her mother, or maybe they teach it at that private school that costs me so much money.

“I was just making conversation.”

Charlie shrugs. “His name is Christian, he’s eighteen, he comes from Bristol and he’s going to be a doctor—a pediatrician to be exact—and he thinks he might work in the Third World for a while, but he’s not my type.”

“You have a type?”

“Yep.”

“May I ask what your type is?”

She sighs, weary of explaining things. “No girl my age should ever date a boy her parents would approve of.”

“Is that a rule?”

“Yep.”

I take her bag and check the departures board. Our train to Oxford leaves in forty minutes.

“So is there any news I should know about? Any latest developments?”

“Nope.”

“How’s school?”

“Good.”

“Emma?”

“She’s fine.”

I’m interrogating her again. Charlie isn’t a talker. Her baseline demeanor is too-cool-to-care.

We buy sandwiches in plastic triangles and soft drinks in plastic bottles. Charlie puts her headphones back in her ears so I can hear the fuzzy thunga-thunga-twang as we board the train and sit opposite each other.

She has dyed her hair since I saw her last and has an annoying fringe that falls over her eyes. I worry about her. She frowns too often. For some reason she seems compelled to figure out life too early, long before she has the equipment.

The train leaves on time and we pass out of London, the wheels playing a jazz percussion beneath my feet. Houses give way to fields—a landscape frozen into still life, where the only signs of life are smudges of smoke rising from chimneys or the headlights of cars waiting at crossings.

A couple are kissing in the seats across the aisle, locked together. Her leg is pressed between his thighs.

“That’s disgusting,” says Charlie.

“They’re just kissing.”

“I can hear suction.”

“It’s a public place.”

“They should get a room.”

I glance at the couple again and feel a Pavlovian twinge of arousal or nostalgia. The girl is young and pretty. She reminds me of Julianne at the same age. Being in love. Belonging to someone.

Just outside of Oxford, the train slows and stops. The wheels creak forward periodically and then shudder to a standstill. Charlie presses her hand against the carriage window and watches a long line of men move across a snowy field, bent at the waist, as though pulling invisible plows.

“Have they lost something?”

“I don’t know.”

The train nudges forward again. Through the sleet-streaked window I see a police car bogged axle deep in snow on a farm track. A muddy Land Rover is parked on the nearby embankment. A circle of men, figures in white, are erecting a canvas tent at the edge of a lake. Spreading a domed arch over the spars, they fight against the wind, which makes the canvas flap and snap until pegs are driven into the frozen earth and ropes are pulled tight.

As the train edges past, I see what they’re trying to shield. At first it looks like cast-off clothing or a dead animal, but then I recognize the human shape: a body, trapped beneath the ice like an insect locked in clear amber.

Charlie sees it too.

“Was there some sort of accident?”

“Looks like it.”

“Did they fall from a train?”

“I don’t know.”

Charlie presses her forehead to the glass.

“Maybe you shouldn’t look,” I say. “You might have nightmares.”

“I’m not six.”

The train shudders and picks up speed again. Snow swirls like confetti from the roof. For a brief moment, the world has tilted out of true and I feel a sense of growing disquiet. There is a void in the world… somebody not coming home.

I’m here.

I want to shout it.

Scream it.

I’m here.

I’M HERE

I’M HERE!

Three days. Something has gone wrong. Tash should be back by now. Maybe George caught her. Maybe he hit her over the head with a shovel and buried her in the forest, which he always said he’d do if we escaped.

Maybe she’s lost. Tash doesn’t have a great sense of direction. Once she managed to get lost at Westgate Shopping Center in Oxford when we were supposed to meet at Apricot to spend my Christmas money on a beaded belt and a pair of dark wash jeans.

That’s the day Tash got into a fight with Bianca Dwyer and threatened to stab her with a pen because she was flirting with Aiden Foster. She would have done it too. Tash once stabbed me with a pen, right through my school tights. I have the world’s tiniest tattoo as evidence. She was angry because I lost the friendship ring that she gave me for my twelfth birthday.

Anyway, Tash has a terrible sense of direction—almost as bad as her taste in boyfriends.

I’m so cold it’s unbelievable. I’m wearing every piece of clothing—and some of Tash’s stuff too. I know she won’t mind.

I pull the blanket over my head. Smell my stale breath. Sweat. Every little while I poke my head out and take a few gulps of clean air and then duck under again.

Maybe I will die of the cold before they find me.

It was different those first few weeks. It was summer and the attic room was hot under the tiles. We had a proper bed, decent food and could watch the TV. George told us we’d be going home soon. He didn’t seem like a monster. He brought us magazines to read and oversized chocolate bars.

I don’t know if George is his real name. Tash came up with it. She said it suited him because he looked like a younger, fatter version of George Clooney, but I think we should have called him Freddy like the guy in Nightmare on Elm Street or that other sicko who wears a hockey mask and carries a chainsaw.

In the beginning George talked a lot about a ransom.

“Your parents are rich,” he told me, “but they don’t want to pay.”

“That’s not true.”

“They don’t want you back.”

“Yes, they do.”

It was another lie. There was never going to be a ransom demand. How can you pay for something if nobody knows the price?

Chained together on the bed, we watched the TV, waiting for news. Meanwhile, the country watched their TVs and waited for news. Everybody had an opinion. Every rumor was dissected. We were kidnapped by an Internet pedophile, according to one story. He’d met us online in a chatroom and made us take off our clothes. As if!

A clairvoyant from Bristol said we were dead and our bodies had been dumped in water. The police dragged the river at Abingdon and searched dozens of wells and drainage ditches.

Mrs. Jarvis, our next-door neighbor, told police she saw a man peering through her bedroom window when she was undressing. Tash laughed at that one. “Jarvis leaves her bedroom curtains open every night, hoping someone might look.”

A London cabbie claimed he’d seen us outside a cinema in Finchley. And a motorist in High Barnet reported seeing two girls in the back of a white van pressing their hands against the windows.

Why is it always a white van? Nobody ever sees kids being snatched by people in purple vans or yellow vans.

Tash’s brother Hayden told reporters that he’d seen a man acting suspiciously in a field not far from Bingham. He took them back to the scene, pointing out the exact place. When he talked about Tash he almost cried, wiping his eyes and threatening to kill anyone who hurt her.

It’s amazing how the truth can be stretched so thin that if people turned it sideways it would probably disappear. It’s like they invented a fantasy version of our lives and pretended it was real.

The Sun offered £200,000 for information leading to our recovery. Suddenly, there were “sightings” in Bristol, Manchester, Aberdeen, Lockerbie and Dover—surges of hope and then despair.

The Oxford Mail revealed there were 984 registered sex offenders in Oxfordshire. More than three hundred lived within a fifteen-mile radius of Bingham. Who knew there were so many perverts living so close?

One of them was old Mr. Purvis, who has a house opposite the green. He’s a creepy old guy who hangs around the train station telling girls they remind him of his daughter.

Police dug up Mr. Purvis’s garden but they didn’t find anything except the skeleton of his dog Buster. By that time, people had marched on the house, calling him a child killer and a pedo.

The police had to rescue Mr. Purvis, taking him away with a blanket over his head. You could just see his baggy trousers and his brown shoes with one sock hanging down. Somebody pulled the blanket away and he looked like a frightened old man.

Things just got wo

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...