- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Vincent Ruiz is lucky to be alive. A bullet in the leg, another through the hand, he is discovered clinging to a buoy in the River Thames, losing blood and consciousness fast. It takes six days for him to come out of his coma, and when he does, his nightmare is only just beginning. Because Vincent has no recollection of what happened, and nobody believes him...

Release date: May 13, 2014

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 432

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

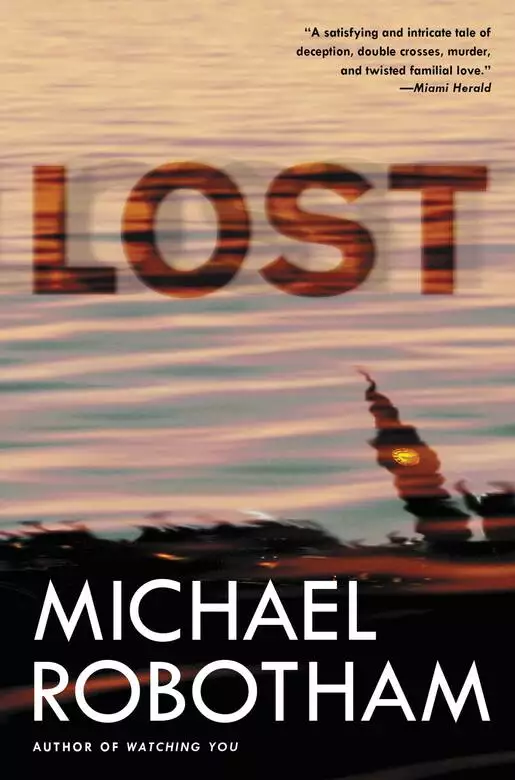

Lost

Michael Robotham

The Thames, London

I remember someone once telling me that you know it’s cold when you see a lawyer with his hands in his own pockets. It’s colder than that now. My mouth is numb and every breath like slivers of ice in my lungs.

People are shouting and shining torches in my eyes. In the meantime, I’m hugging this big yellow-painted buoy like it’s Marilyn Monroe. A very fat Marilyn Monroe, after she took all the pills and went to seed.

My favorite Monroe film is Some Like It Hot with Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis. I don’t know why I should think of that now, although how anyone could mistake Jack Lemmon for a woman is beyond me.

A guy with a really thick mustache and pizza breath is panting in my ear. He’s wearing a life vest and trying to peel my fingers away from the buoy. I’m too cold to move. He wraps his arms around my chest and pulls me backwards through the water. More people, silhouetted against the lights, take hold of my arms, lifting me onto the deck.

“Jesus, look at his leg!” someone says.

“He’s been shot!”

Who are they talking about?

People are shouting all over again, yelling for bandages and plasma. A black guy with a gold earring slides a needle into my arm and puts a bag over my face.

“Someone get some blankets. Let’s keep this guy warm.”

“He’s palping at one-twenty.”

“One-twenty?”

“Palping at one-twenty.”

“Any head injuries?”

“That’s negative.”

The engine roars and we’re moving. I can’t feel my legs. I can’t feel anything—not even the cold anymore. The lights are also disappearing. Darkness has seeped into my eyes.

“Ready?”

“Yeah.”

“One, two, three.”

“Watch the IV lines. Watch the IV lines.”

“I got it.”

“Bag a couple of times.”

“OK.”

The guy with pizza breath is puffing really hard now, running alongside the gurney. His fist is in front of my face, pressing a bag to force air into my lungs. They lift again and square lights pass overhead. I can still see.

A siren wails in my head. Every time we slow down it gets louder and closer. Someone is talking on a radio. “We’ve pumped two liters of fluid. He’s on his fourth unit of blood. He’s bleeding out. Systolic pressure dropping.”

“He needs volume.”

“Squeeze in another bag of fluid.”

“He’s seizing!”

“He’s seizing. See that?”

One of the machines has gone into a prolonged cry. Why don’t they turn it off?

Pizza breath rips open my shirt and slaps two pads on my chest.

“CLEAR!” he yells.

The pain almost blows the top of my skull clean off.

He does that again and I’ll break his arms.

“CLEAR!”

I swear to God I’m going to remember you, pizza breath. I’m going to remember exactly who you are. And when I get out of here I’m coming looking for you. I was happier in the river. Take me back to Marilyn Monroe.

I am awake now. My eyelids flutter as if fighting gravity. Squeezing them shut, I try again, blinking into the darkness.

Turning my head, I can make out orange dials on a machine near the bed and a green blip of light sliding across a liquid-crystal display window like one of those stereo systems with bouncing waves of colored light.

Where am I?

Beside my head is a chrome stand that catches stars on its curves. Suspended from a hook is a plastic sachet bulging with a clear fluid. The liquid trails down a pliable plastic tube and disappears under a wide strip of surgical tape wrapped around my left forearm.

I’m in a hospital room. There is a pad on the bedside table. Reaching towards it, I suddenly notice my left hand—not so much my hand as a finger. It’s missing. Instead of a digit and a wedding ring I have a lump of gauze dressing. I stare at it idiotically, as though this is some sort of magic trick.

When the twins were youngsters, we had a game where I pulled off my thumb and if they sneezed it would come back again. Michael used to laugh so hard he almost wet his pants.

Fumbling for the pad, I read the letterhead: “St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington, London.” There is nothing in the drawer except a Bible and a copy of the Koran.

I spy a clipboard hanging at the end of the bed. Reaching down, I feel a sudden pain that explodes from my right leg and shoots out of the top of my head. Christ! Do not, under any circumstances, do that again.

Curled up in a ball, I wait for the pain to go away. Closing my eyes, I take a deep breath. If I concentrate very hard on a particular point just under my jawbone, I actually feel the blood sliding back and forth beneath my skin, squeezing into smaller and smaller channels, circulating oxygen.

My estranged wife Miranda was such a lousy sleeper she said my heart kept her awake because it beat too loudly. I didn’t snore or wake with the night terrors, but my heart pumped up a riot. This has been listed among Miranda’s grounds for divorce. I’m exaggerating, of course. She doesn’t need extra justification.

I open my eyes again. The world is still here.

Taking a deep breath, I grip the bedclothes and raise them a few inches. I still have two legs. I count them. One. Two. The right leg is bandaged in layers of gauze taped down at the edges. Something has been written in a felt-tip pen down the side of my thigh but I can’t read what it says.

Further down I can see my toes. They wave hello to me. “Hello toes,” I whisper.

Tentatively, I reach down and cup my genitals, rolling my testicles between my fingers.

A nurse slips silently through the curtains. Her voice startles me. “Is this a very private moment?”

“I was—I was—just checking.”

“Well, I think you should consider buying that thing dinner first.”

Her accent is Irish and her eyes are as green as mown grass. She presses the call button above my head. “Thank goodness you’re finally awake. We were very worried about you.” She taps the bag of fluid and checks the flow control. Then she straightens my pillows.

“What happened? How did I get here?”

“You were shot.”

“Who shot me?”

She laughs. “Oh, don’t ask me. Nobody ever tells me things like that.”

“But I can’t remember anything. My leg… my finger…”

“The doctor should be here soon.”

She doesn’t seem to be listening. I reach out and grab her arm. She tries to pull away, suddenly frightened of me.

“You don’t understand—I can’t remember! I don’t know how I got here.”

She glances at the emergency button. “They found you floating in the river. That’s what I heard them say. The police have been waiting for you to wake up.”

“How long have I been here?”

“Eight days… you were in a coma. I thought you might be coming out yesterday. You were talking to yourself.”

“What did I say?”

“You kept asking about a girl—saying you had to find her.”

“Who?”

“You didn’t say. Please let go of my arm. You’re hurting me.”

My fingers open and she steps well away, rubbing her forearm. She won’t come close again.

My heart won’t slow down. It is pounding away, getting faster and faster, like Chinese drums. How can I have been here eight days?

“What day is it today?”

“October the third.”

“Did you give me drugs? What have you done to me?”

She stammers, “You’re on morphine for the pain.”

“What else? What else have you given me?”

“Nothing.” She glances again at the emergency button. “The doctor is coming. Try to stay calm or he’ll have to sedate you.”

She’s out of the door and won’t come back. As it swings closed I notice a uniformed policeman sitting on a chair outside the door, with his legs stretched out like he’s been there for a while.

I slump back in bed, smelling bandages and dried blood. Holding up my hand I look at the gauze bandage, trying to wiggle the missing finger. How can I not remember?

For me there has never been such a thing as forgetting, nothing is hazy or vague or frayed at the edges. I hoard memories like a miser counts his gold. Every scrap of a moment is kept as long as it has some value.

I don’t see things photographically. Instead I make connections, spinning them together like a spider weaving a web, threading one strand into the next. That’s why I can reach back and pluck details of criminal cases from five, ten, fifteen years ago and remember them as if they happened only yesterday. Names, dates, places, witnesses, perpetrators, victims—I can conjure them up and walk through the same streets, have the same conversations, hear the same lies.

Now for the first time I’ve forgotten something truly important. I can’t remember what happened and how I finished up here. There is a black hole in my mind like a dark shadow on a chest X-ray. I’ve seen those shadows. I lost my first wife to cancer. Black holes suck everything into them. Not even light can escape.

Twenty minutes go by and then Dr. Bennett sweeps through the curtains. He’s wearing jeans and a bow tie under his white coat.

“Detective Inspector Ruiz, welcome back to the land of the living and high taxation.” He sounds very public school and has one of those foppish Hugh Grant fringes that falls across his forehead like a serviette on a thigh.

Shining a pen torch in my eyes, he asks, “Can you wiggle your toes?”

“Yes.”

“Any pins and needles?”

“No.”

He pulls back the bedclothes and scrapes a key along the sole of my right foot. “Can you feel that?”

“Yes.”

“Excellent.”

Picking up the clipboard hanging at the end of my bed, he scrawls his initials with a flick of the wrist.

“I can’t remember anything.”

“About the accident.”

“It was an accident?”

“I have no idea. You were shot.”

“Who shot me?”

“You don’t remember?”

“No.”

This conversation is going around in circles.

Dr. Bennett taps the pen against his teeth, contemplating this answer. Then he pulls up a chair and sits on it backwards, draping his arms over the backrest.

“You were shot. One bullet entered just above your gracilis muscle on your right leg leaving a quarter-inch hole. It went through the skin, then the fat layer, through the pectineus muscle, just medial to the femoral vessels and nerve, through the quadratus femoris muscle, through the head of the biceps femoris and through the gluteus maximus before exiting through the skin on the other side. The exit wound was far more impressive. It blew a hole four inches across. Gone. No flap. No pieces. Your skin just vaporized.”

He whistles impressively through his teeth. “You had a pulse when they found you but you were bleeding out. Then you stopped breathing. You were dead but we brought you back.”

He holds up his thumb and forefinger. “The bullet missed your femoral artery by this far.” I can barely see a gap between them. “Otherwise you would have bled to death in three minutes. Apart from the bullet we had to deal with infection. Your clothes were filthy. God knows what was in that water. We’ve been pumping you full of antibiotics. Bottom line, Inspector, you are one lucky puppy.”

Is he kidding? How much luck does it take to get shot?

I hold up my hand. “What about my finger?”

“Gone, I’m afraid, just above the first knuckle.”

A skinny-looking intern with a number two cut pokes his head through the curtains. Dr. Bennett lets out a low-pitched growl that only underlings can hear. Rising from the chair, he buries his hands in the pockets of his white coat.

“Will that be all?”

“Why can’t I remember?”

“I don’t know. It’s not really my field, I’m afraid. We can run some tests. You’ll need a CT scan or an MRI to rule out a skull fracture or hemorrhage. I’ll call neurology.”

“My leg hurts.”

“Good. It’s getting better. You’ll need a walking frame or crutches. A physiotherapist will come and talk to you about a program to help you strengthen your leg.” He flips his fringe and turns to leave. “I’m sorry about your memory, Inspector. Be thankful you’re alive.”

He’s gone, leaving a scent of aftershave and superiority. Why do surgeons cultivate this air of owning the world? I know I should be grateful. Maybe if I could remember what happened I could trust the explanations more.

So I should be dead. I always suspected that I would die suddenly. It’s not that I’m particularly foolhardy but I have a knack of taking shortcuts. Most people die only the once. Now I’ve had two lives. Throw in three wives and I’ve had more than my fair share of living. (I’ll definitely forgo the three wives, should someone want them back.)

My Irish nurse is back again. Her name is Maggie and she has one of those reassuring smiles they teach in nursing school. She has a bowl of warm water and a sponge.

“Are you feeling better?”

“I’m sorry I frightened you.”

“That’s OK. Time for a bath.”

She pulls back the covers and I drag them up again.

“There’s nothing under there I haven’t seen,” she says.

“I beg to differ. I have a pretty fair recollection of how many women have danced with old Johnnie One-Eye and, unless you were that girl in the back row of the Shepherd’s Bush Empire during a Yardbirds concert in 1963, I don’t think you’re one of them.”

“Johnnie One-Eye?”

“My oldest friend.”

She shakes her head and looks sorry for me.

A familiar figure appears from behind her—a short square man, with no neck and a five-o’clock shadow. Campbell Smith is a Chief Superintendent, with a crushing handshake and a no-brand smile. He’s wearing his uniform, with polished silver buttons and a shirt collar so highly starched it threatens to decapitate him.

Everyone claims to like Campbell—even his enemies—but few people are ever happy to see him. Not me. Not today. I remember him! That’s a good sign.

“Christ, Vincent, you gave us a scare!” he booms. “It was touch and go for a while. We were all praying for you—everyone at the station. See all the cards and flowers?”

I turn my head and look at a table piled high with flowers and bowls of fruit.

“Someone shot me,” I say, incredulously.

“Yes,” he replies, pulling up a chair. “We need to know what happened.”

“I don’t remember.”

“You didn’t see them?”

“Who?”

“The people on the boat.”

“What boat?” I look at him blankly.

His voice suddenly grows louder. “You were found floating in the Thames shot to shit and less than a mile away there was a boat that looked like a floating abattoir. What happened?”

“I don’t remember.”

“You don’t remember the massacre?”

“I don’t remember the fucking boat.”

Campbell has dropped any pretence of affability. He paces the room, bunching his fists and trying to control himself.

“This isn’t good, Vincent. This isn’t pretty. Did you kill anyone?”

“Today?”

“Don’t joke with me. Did you discharge your firearm? Your service pistol was signed out of the station armory. Are we going to find bodies?”

Bodies? Is that what happened?

Campbell rubs his hands through his hair in frustration.

“I can’t tell you the crap that’s flying already. There’s going to be a full inquiry. The Commissioner is demanding answers. The press will have a fucking field day. The blood of three people was found on that boat, including yours. Forensics says at least one of them must have died. They found brains and skull fragments.”

The walls seem to dip and sway. Maybe it’s the morphine or the closeness of the air. How could I have forgotten something like that?

“What was I doing on that boat? It must have been a police operation—”

“No,” he declares angrily, “you weren’t working a case. This wasn’t a police operation. You were on your own.”

We have an old-fashioned staring contest. I own this one. I might never blink again. Morphine is the answer. God, it feels good.

Finally Campbell slumps into a chair and plucks a handful of grapes from a brown paper bag beside the bed.

“What is the last thing you remember?”

We sit in silence as I try to recover shreds of a dream. Pictures float in and out of my head, dim and then sharp: a yellow life buoy, Marilyn Monroe…

“I remember ordering a pizza.”

“Is that it?”

“Sorry.”

Staring at the gauze dressing on my hand, I marvel at how the missing finger feels itchy. “What was I working on?”

Campbell shrugs. “You were on leave.”

“Why?”

“You needed a rest.”

He’s lying to me. Sometimes I think he forgets how far we go back. We did our training together at the Police Staff College, Bramshill. And I introduced him to his wife Maureen at a barbecue thirty-five years ago. She has never completely forgiven me. I don’t know what upsets her most—my three marriages or the fact that I palmed her off on to someone else.

It’s been a long while since Campbell called me buddy and we haven’t shared a beer since he made Chief Superintendent. He’s a different man. No better and no worse, just different.

He spits a grape seed into his hand. “You always thought you were better than me, Vincent, but I got promoted ahead of you.”

You were a brown-noser.

“I know you think I’m a brown-noser. (He’s reading my mind.) But I was just smarter. I made the right contacts and let the system work for me instead of fighting against it. You should have retired three years ago, when you had the chance. Nobody would have thought any less of you. We would have given you a big send-off. You could have settled down, played a bit of golf, maybe even saved your marriage.”

I wait for him to say something else but he just stares at me with his head cocked to one side.

“Vincent, would you mind if I made an observation?” He doesn’t wait for my answer. “You put a pretty good face on things considering all that’s happened but the feeling I get from you is… well… you’re a sad man. But it’s something more than that… you’re angry.”

Embarrassment prickles like heat rash under my hospital gown. He doesn’t stop.

“Some people find solace in religion, Vincent, and others have people they can talk to. I know that’s not your style. Look at you! You hardly see your kids. You live alone… Now you’ve gone and fucked up your career. I can’t help you anymore. I told you to leave this alone.”

“What was I supposed to leave alone?”

He doesn’t answer. Instead he picks up his hat and polishes the brim with his sleeve. Any moment now he’s going to turn and tell me what he means. Only he doesn’t; he keeps on walking out of the door and along the corridor.

My grapes have also gone. The stalks look like dead trees on a crumpled brown paper plain. Beside them a basket of flowers has started to wilt. The begonias and tulips are losing their petals like fat fan dancers and dusting the top of the table with pollen. A small white card embossed with a silver scroll is wedged between the stems. I can’t read the message.

Some bastard shot me! It should be etched in my memory. I should be able to relive it over and over again like those whining victims on daytime talk shows who have personal injury lawyers on speed dial. Instead, I remember nothing. And no matter how many times I squeeze my eyes shut and bang my fists on my forehead it doesn’t change.

The really strange thing is what I imagine I remember. For instance, I recall seeing silhouettes against bright lights; masked men wearing plastic shower caps and paper slippers, who were discussing cars, pension plans and football results. Of course this could have been a near-death experience. I was given a glimpse of Hell and it was full of surgeons.

Perhaps, if I start with the simple stuff, I may get to the point where I can remember what happened to me. Staring at the ceiling, I silently spell my name: Vincent Yanko Ruiz; born 11 December 1945. I am a Detective Inspector of the London Metropolitan Police and the head of the Serious Crime Group (Western Division). I live in Rainville Road, Fulham…

I used to say I would pay good money to forget most of my life. Now I want the memories back.

2

I know only two people who have been shot. One was a chap I went through police training college with. His name was Angus Lehmann and he wanted to be first at everything—first in his exams, first to the bar, first to get promoted…

A few years back he led a raid on a drugs factory in Brixton and was first through the door. An entire magazine from a semi-automatic took his head clean off. There’s a lesson in that somewhere.

A farmer in our valley called Bruce Curley is the other one. He shot himself in the foot when he tried to chase his wife’s lover out of the bedroom window. Bruce was fat with gray hair sprouting from his ears and Mrs. Curley used to cower like a dog whenever he raised a hand. Shame he didn’t shoot himself between the eyes.

During my police training we did a firearms course. The instructor was a Geordie with a head like a billiard ball and he took against me from the first day because I suggested the best way to keep a gun barrel clean was to cover it with a condom.

We were standing on the live firing range, freezing our bollocks off. He pointed out the cardboard cutout at the end of the range. It was a silhouette of a crouching gun-wielding villain with a painted white circle over his heart and another on his head.

Taking a service pistol the Geordie crouched down with his legs apart and squeezed off six shots—a heartbeat between each of them—every one grouped in the upper circle.

Flicking the smoking clip into his hand, he said, “Now I don’t expect any of you to do that but at least try to hit the fucking target. Who wants to go first?”

Nobody volunteered.

“How about you, condom boy?”

The class laughed.

I stepped forward and raised my revolver. I hated how good it felt in my hand. The instructor said, “No, not like that, keep both eyes open. Crouch. Count and squeeze.”

Before he could finish the gun kicked in my hand, rattling the air and something deep inside me.

The cutout swayed from side to side as the pulley dragged it down the range towards us. Six shots, each so close together they formed a ragged hole through the cardboard.

“He shot out his arsehole,” someone muttered in astonishment.

“Right up the Khyber Pass.”

I didn’t look at the instructor’s face. I turned away, checked the chamber, put on the safety catch and removed my earplugs.

“You missed,” he said triumphantly.

“If you say so, sir.”

I wake with a sudden jolt and it takes a while for my heart to settle. I look at my watch—not so much at the time but the date. I want to make sure I haven’t slept for too long or lost any more time.

It’s been two days since I regained consciousness. A man is sitting by the bed.

“My name is Wickham,” he says, smiling. “I’m a neurologist.”

He looks like one of those doctors you see on daytime chat shows.

“I once saw you play rugby for Harlequins against London Scottish,” he says. “You would have made the England team that year if you hadn’t been injured. I played a bit of rugby myself. Never higher than seconds…”

“Really, what position?”

“Outside center.”

I figured as much—he probably touched the ball twice a game and is still talking about the tries he could have scored.

“I have the results of your MRI scan,” he says, opening a folder. “There is no evidence of a skull fracture, aneurysms or a hemorrhage.” He glances up from his notes. “I want to run some neurological tests to help establish what you’ve forgotten. It means answering some questions about the shooting.”

“I don’t remember it.”

“Yes, but I want you to answer regardless—even if that means guessing. It’s called a forced-choice recognition test. It forces you to make choices.”

I think I understand, although I don’t see the point.

“How many people were on the boat?”

“I don’t remember.”

Wickham reiterates, “You have to make a choice.”

“Four.”

“Was there a full moon?”

“Yes.”

“Was the name of the boat the Charmaine?”

“No.”

“How many engines did it have?”

“One.”

“Was it a stolen boat?”

“Yes.”

“Was the engine running?”

“No.”

“Were you anchored or drifting?”

“Drifting.”

“Were you carrying a weapon?”

“Yes.”

“Did you fire your weapon?”

“No.”

This is ridiculous! What possible good does it do? I’m guessing the answers.

Suddenly, it dawns on me. They think I’m faking amnesia. This isn’t a test to see how much I remember—they’re testing the validity of my symptoms. They’re forcing me to make choices so they can work out what percentage of questions I answer correctly. If I’m telling the truth, pure guesswork should mean half of my answers are correct. Anything significantly above or below 50 percent could mean I’m trying to “influence” the result by deliberately getting things right or wrong.

The chance of someone with memory loss answering only ten questions correctly out of fifty, for example, is smaller than 5 percent. I know enough about statistics to see the objective.

Wickham has been taking notes. No doubt he’s studying the distribution of my answers—looking for patterns that might indicate something other than random chance.

Stopping him, I ask, “Who wrote these questions?”

“I don’t know.”

“Guess.”

He blinks at me.

“Come on, Doc, true or false? I’ll accept a guess. Is this a test to see if I’m faking memory loss?”

“I don’t know what you mean,” he stammers.

“If I can guess the answer, so can you. Who put you up to this—Internal Affairs or Campbell Smith?”

Struggling to his feet, he tucks the clipboard under his arm and turns towards the door. I wish I’d met him on the rugby field. I’d have driven his head into a muddy hole.

Swinging my legs out of bed, I put one foot on the floor. The lino is cool and slightly sticky. Gulping hard on the pain, I slide my forearms into the plastic cuffs of the crutches.

I’m supposed to be using a support frame on wheels but I’m too vain. I’m not going to walk around in a chrome cage like some geriatric in a post office queue. I look in the cupboard for my clothes. Empty.

I know it sounds paranoid but they’re not telling me everything. Someone must know what I was doing on the river. Someone will have heard the shots or seen something. Why haven’t they found any bodies?

Halfway down the corridor I see Campbell talking to Wickham. Two detectives are with them. I recognize one of them: John Keebal. I used to work with him until he joined the Met’s Anti-Corruption Group, otherwise known as the Ghost Squad.

Keebal is one of those coppers who call all gays “fudge-packers” and Asians “Pakis.” He is loud, bigoted and totally obsessed with the job. When the Marchioness riverboat sank in the Thames, he did thirteen death-knocks before lunch-time, telling people their kids had drowned. He knew exactly what to say and when to stop talking. A man like that can’t be all bad.

“Where do you think you’re going?” asks Campbell.

“I thought I might get some fresh air.”

Keebal interrupts, “Yeah, just got a whiff of something myself.”

I push past them heading for the lift.

“You can’t possibly leave,” says Wickham. “Your dressing has to be changed every few days. You need painkillers.”

“Fill my pockets and I’ll self-administer.”

Campbell grabs my arm. “Don’t be so bloody foolish.”

I realize I’m shaking.

“Have you found anyone? Any… any bodies.”

“No.”

“I’m not faking this, you know. I really can’t remember.”

“I know.”

He steers me away from the others. “But you know the drill. The IPCC has to investigate.”

“What’s Keebal doing here?”

“He wants to talk to you.”

“Do I need a lawyer?”

Campbell laughs but it doesn’t reassure me like it should. Before I can weigh up my options, Keebal leads me down the corridor to the hospital lounge—a stark, windowless place, with burnt orange sofas and posters of healthy people. He unbuttons his jacket and takes a seat, waiting for me to lever myself down from my crutches.

“I hear you nearly met the Grim Reaper.”

“He offered me a room with a view.”

“And you turned him down?”

“I’m not a good traveler.”

For the next ten minutes we shoot the breeze about mutual acquaintances and old times working in west London. He asks about my mother and I tell him she’s in a retirement village.

“Some of those places can be pretty expensive.”

“Yep.”

“Where you living nowadays?”

“Right here.”

The coffee arrives and Keebal keeps talking. He gives me his opinion on the proliferation of firearms, random violence and senseless crimes. The police are becoming easy targets and scapegoats all at once. I know what he’s trying to do. He wants to draw me in with a spiel about good guys having to stick together.

Keebal is one of those police officers who adopt a warrior ethic as though something separates them from normal society. They listen to politicians talk about the war on crime and the war on drugs and the war on terror and they start picturing themselves as soldiers fighting to keep the streets safe.

“How many times have you put your life on the line, Ruiz? You think any of the bastards care? The left call us pigs and the right call us

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...