- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

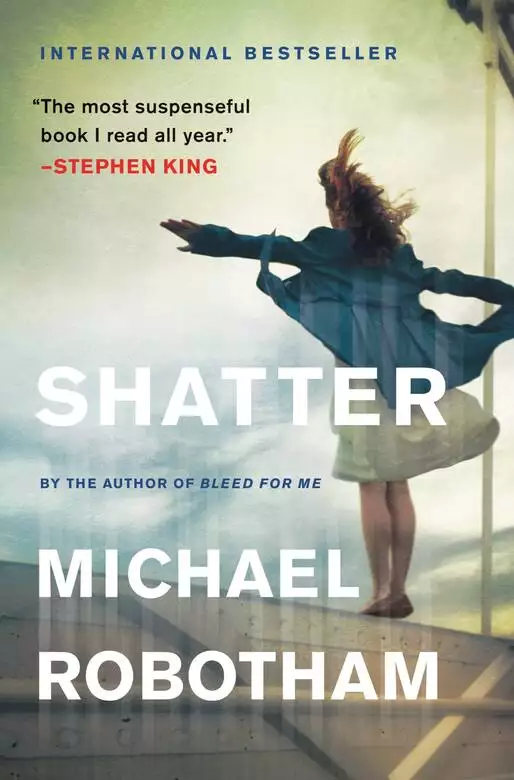

In this fast-paced thriller, a psychologist faces off against a killer who destroys his victims from the inside out.

Joe O’Loughlin is in familiar territory—standing on a bridge high above a flooded gorge, trying to stop a distraught woman from jumping. “You don’t understand,” she whispers, and lets go. Joe is haunted by his failure to save the woman, until her teenage daughter finds him and reveals that her mother would never have committed suicide—not like that. She was terrified of heights.

What could have driven her to commit such a desperate act? Whose voice? What evil?

Having devoted his career to repairing damaged minds, Joe must now confront an adversary who tears them apart. With pitch-perfect dialogue, believable characters, and astonishingly unpredictable plot twists, Shatter is guaranteed to keep even the most avid thriller readers riveted long into the night.

A Blackstone Audio production.

Release date: January 26, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 496

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Shatter

Michael Robotham

It’s eleven o’clock in the morning, late September, and outside it’s raining so hard that cows are floating down rivers and birds are resting on their bloated bodies.

The lecture theater is full. Tiered seats rise at a gentle angle between the stairs on either side of the auditorium, climbing into darkness. Mine is an audience of pale faces, young and earnest, hung over. Fresher’s Week is in full swing and many of them have waged a mental battle to be here, weighing up whether to attend any lectures or go back to bed. A year ago they were watching teen movies and spilling popcorn. Now they’re living away from home, getting drunk on subsidized alcohol and waiting to learn something.

I walk to the center of the stage and clamp my hands on the lectern as if frightened of falling over.

“My name is Professor Joseph O’Loughlin. I am a clinical psychologist and I’ll be taking you through this introductory course in behavioral psychology.”

Pausing a moment, I blink into the lights. I didn’t think I would be nervous lecturing again but now I suddenly doubt if I have any knowledge worth imparting. I can still hear Bruno Kaufman’s advice. (Bruno is the head of the psychology department at the university and is blessed with a perfect Teutonic name for the role.) He told me, “Nothing we teach them will be of the slightest possible use to them in the real world, old boy. Our task is to offer them a bullshit meter.”

“A what?”

“If they work hard and take a little on board, they will learn to detect when someone is telling them complete bullshit.”

Bruno had laughed and I found myself joining him.

“Go easy on them,” he added. “They’re still clean and perky and well-fed. A year from now they’ll be calling you by your first name and thinking they know it all.”

How do I go easy on them, I want to ask him now. I’m new at this too. Breathing deeply, I begin again.

“Why does a well-spoken university graduate studying urban preservation fly a passenger plane into a skyscraper, killing thousands of people? Why does a boy, barely into his teens, spray a schoolyard with bullets, or a teenage mother give birth in a toilet and leave the baby in the wastepaper bin?”

Silence.

“How did a hairless primate evolve into a species that manufactures nuclear weapons, watches Celebrity Big Brother and asks questions about what it means to be human and how we got here? Why do we cry? Why are some jokes funny? Why are we inclined to believe or disbelieve in God? Why do we get turned on when someone sucks our toes? Why do we have trouble remembering some things, yet can’t get that annoying Britney Spears song out of our heads? What causes us to love or hate? Why are we each so different?”

I look at the faces in the front rows. I have captured their attention, for a moment at least.

“We humans have been studying ourselves for thousands of years, producing countless theories and philosophies and astonishing works of art and engineering and original thought, yet in all that time this is how much we’ve learned.” I hold up my thumb and forefinger a fraction of an inch apart.

“You’re here to learn about psychology—the science of the mind; the science that deals with knowing, believing, feeling and desiring; the least understood science of them all.”

My left arm trembles at my side.

“Did you see that?” I ask, raising the offending arm. “It does that occasionally. Sometimes I think it has a mind of its own but of course that’s impossible. One’s mind doesn’t reside in an arm or a leg.

“Let me ask you all a question. A woman walks into a clinic. She is middle-aged, well-educated, articulate and well-groomed. Suddenly, her left arm leaps to her throat and her fingers close around her windpipe. Her face reddens. Her eyes bulge. She is being strangled. Her right hand comes to her rescue. It peels back the fingers and wrestles her left hand to her side. What should I do?”

Silence.

A girl in the front row nervously raises her arm. She has short reddish hair separated in feathery wisps down the fluted back of her neck. “Take a detailed history?”

“It’s been done. She has no history of mental illness.”

Another hand rises. “It is an issue of self-harm.”

“Obviously, but she doesn’t choose to strangle herself. It is unwanted. Disturbing. She wants help.”

A girl with heavy mascara brushes hair behind her ear with one hand. “Perhaps she’s suicidal.”

“Her left hand is. Her right hand obviously doesn’t agree. It’s like a Monty Python sketch. Sometimes she has to sit on her left hand to keep it under control.”

“Is she depressed?” asks a youth with a gypsy earring and gel in his hair.

“No. She’s frightened but she can see the funny side of her predicament. It seems ridiculous to her. Yet at her worst moments she contemplates amputation. What if her left hand strangles her in the night, when her right hand is asleep?”

“Brain damage?”

“There are no obvious neurological deficits—no paralysis or exaggerated reflexes.”

The silence stretches out, filling the air above their heads, drifting like strands of web in the warm air.

A voice from the darkness fills the vacuum. “She had a stroke.”

I recognize the voice. Bruno has come to check up on me on my first day. I can’t see his face in the shadows but I know he’s smiling.

“Give that man a cigar,” I announce.

The keen girl in the front row pouts. “But you said there was no brain damage.”

“I said there were no obvious neurological deficits. This woman had suffered a small stroke on the right side of her brain in an area that deals with emotions. Normally, the two halves of our brain communicate and come to an agreement but in this case it didn’t happen and her brain fought a physical battle using each side of her body.

“This case is fifty years old and is one of the most famous in the study of the brain. It helped a neurologist called Dr. Kurt Goldstein develop one of the first theories of the divided brain.”

My left arm trembles again, but this time it is oddly reassuring.

“Forget everything you’ve been told about psychology. It will not make you a better poker player, nor will it help you pick up girls or understand them any better. I have three at home and they are a complete mystery to me.

“It is not about dream interpretation, ESP, multiple personalities, mind-reading, Rorschach Tests, phobias, recovered memories or repression. And most importantly—it is not about getting in touch with yourself. If that’s your ambition I suggest you buy a copy of Big Jugs magazine and find a quiet corner.”

There are snorts of laughter.

“I don’t know any of you yet, but I know things about you. Some of you want to stand out from the crowd and others want to blend in. You’re possibly looking at the clothes your mother packed you and planning an expedition to H&M tomorrow to purchase something distressed by a machine that will express your individuality by making you look like everyone else on campus.

“Others among you might be wondering if it’s possible to get liver damage from one night of drinking, and speculating on who set off the fire alarm in Halls at three o’clock this morning. You want to know if I’m a hard marker or if I’ll give you extensions on assignments or whether you should have taken politics instead of psychology. Stick around and you’ll get some answers—but not today.”

I walk back to the center of the stage and stumble slightly.

“I will leave you with one thought. A piece of human brain the size of a grain of sand contains one hundred thousand neurons, two million axons and one billion synapses all talking to each other. The number of permutations and combinations of activity that are theoretically possible in each of our heads exceeds the number of elementary particles in the universe.”

I pause and let the numbers wash over them. “Welcome to the great unknown.”

“Dazzling, old boy, you put the fear of God into them,” says Bruno, as I gather my papers. “Ironic. Passionate. Amusing. You inspired them.”

“It was hardly Mr. Chips.”

“Don’t be so modest. None of these young philistines have ever heard of Mr. Chips. They’ve grown up reading Harry Potter and the Stoned Philosopher.”

“I think it’s ‘the Philosopher’s Stone.’ ”

“Whatever. With that little affectation of yours, Joseph, you have everything it takes to be much loved.”

“Affectation?”

“Your Parkinson’s.”

He doesn’t bat an eyelid when I stare at him in disbelief. I tuck my battered briefcase under my arm and make my way towards the side door of the lecture hall.

“Well, I’m pleased you think they were listening,” I say.

“Oh, they never listen,” says Bruno. “It’s a matter of osmosis; occasionally something sinks through the alcoholic haze. But you did guarantee they’ll come back.”

“How so?”

“They won’t know how to lie to you.”

His eyes fold into wrinkles. Bruno is wearing trousers that have no pockets. For some reason I’ve never trusted a man who has no use for pockets. What does he do with his hands?

The corridors and walkways are full of students. A girl approaches. I recognize her from the lecture. Clear-skinned, wearing desert boots and black jeans, her heavy mascara makes her look raccoon-eyed with a secret sadness.

“Do you believe in evil, Professor?”

“Excuse me?”

She asks the question again, clutching a notebook to her chest.

“I think the word ‘evil’ is used too often and has lost value.”

“Are people born that way or does society create them?”

“They are created.”

“So there are no natural psychopaths?”

“They’re too rare to quantify.”

“What sort of answer is that?”

“It’s the right one.”

She wants to ask me something else but struggles to find courage. “Would you agree to an interview?” she blurts suddenly.

“What for?”

“The student newspaper. Professor Kaufman says you’re something of a celebrity.”

“I hardly think…”

“He says you were charged with murdering a former patient and beat the rap.”

“I was innocent.”

The distinction seems lost on her. She’s still waiting for an answer.

“I don’t give interviews. I’m sorry.”

She shrugs and turns, about to leave. Something else occurs to her. “I enjoyed the lecture.”

“Thank you.”

She disappears down the corridor. Bruno looks at me sheepishly. “Don’t know what she’s talking about, old boy. Wrong end of the stick.”

“What are you telling people?”

“Only good things. Her name is Nancy Ewers. She’s a bright young thing. Studying Russian and politics.”

“Why is she writing for the newspaper?”

“ ‘Knowledge is precious whether or not it serves the slightest human use.’ ”

“Who said that?”

“A. E. Housman.”

“Wasn’t he a communist?”

“A pillow-biter.”

It is still raining. Teeming. For weeks it has been like this. Forty days and forty nights must be getting close. An oily wave of mud, debris and sludge is being swept across the West Country, making roads impassable and turning basements into swimming pools. There are radio reports of flooding in the Malago Valley, Hartcliffe Way and Bedminster. Warnings have been issued for the Avon, which burst its banks at Evesham. Locks and levees are under threat. People are being evacuated. Animals are drowning.

The quadrangle is washed by rain, driven sideways in sheets. Students huddle under coats and umbrellas, making a dash for their next lecture or the library. Others are staying put, mingling in the foyer. Bruno observes the prettier girls without ever making it obvious.

It was he who suggested I lecture—two hours a week and four tutorials of half an hour each. Behavioral psychology. How hard could it be?

“Do you have an umbrella?” he asks.

“Yes.”

“We’ll share.”

My shoes are full of water within seconds. Bruno holds the umbrella and shoulders me as we run. As we near the psychology department, I notice a police car parked in the emergency bay. A young black constable steps from inside wearing a raincoat. Tall, with short-cropped hair, he hunches his shoulders slightly as if beaten down by the rain.

“Dr. Kaufman?”

Bruno acknowledges him with a half-nod.

“We have a situation on the Clifton Bridge.”

Bruno groans. “No, no, not now.”

The constable doesn’t expect a refusal. Bruno pushes past him, heading towards the glass doors to the psychology building, still holding my umbrella.

“We tried to phone,” yells the officer. “I was told to come and get you.”

Bruno stops and turns back, muttering expletives.

“There must be someone else. I don’t have the time.”

Rain leaks down my neck. I ask Bruno what’s wrong.

Suddenly he changes tack. Jumping over a puddle, he returns my umbrella as though passing on the Olympic torch.

“This is the man you really want,” he says to the officer. “Professor Joseph O’Loughlin, my esteemed colleague, a clinical psychologist of great repute. An old hand. Very experienced at this sort of thing.”

“What sort of thing?”

“A jumper.”

“Pardon?”

“On the Clifton Suspension Bridge,” adds Bruno. “Some halfwit doesn’t have enough sense to get out of the rain.”

The constable opens the car door for me. “Female. Early forties,” he says.

I still don’t understand.

Bruno adds, “Come on, old boy. It’s a public service.”

“Why don’t you do it?”

“Important business. A meeting with the chancellor. Heads of Department.” He’s lying. “False modesty isn’t necessary, old boy. What about that young chap you saved in London? Well-deserved plaudits. You’re far more qualified than me. Don’t worry. She’ll most likely jump before you get there.”

I wonder if he hears himself sometimes.

“Must dash. Good luck.” He pushes through the glass doors and disappears inside the building.

The officer is still holding the car door. “They’ve blocked off the bridge,” he explains. “We really must hurry, sir.”

Wipers thrash and a siren wails. From inside the car it sounds strangely muted and I keep looking over my shoulder expecting to see an approaching police car. It takes me a moment to realize that the siren is coming from somewhere closer, beneath the bonnet.

Masonry towers appear on the skyline. It is Brunel’s masterpiece, the Clifton Suspension Bridge, an engineering marvel from the age of steam. Taillights blaze. Traffic is stretched back for more than a mile on the approach. Sticking to the apron of the road, we sweep past the stationary cars and pull up at a roadblock where police in fluorescent vests control onlookers and unhappy motorists.

The constable opens the door for me and hands me my umbrella. A sheet of rain drives sideways and almost rips it from my hands. Ahead of me the bridge appears deserted. The masonry towers support massive sweeping interlinking cables that curve gracefully to the vehicle deck and rise again to the opposite side of the river.

One of the attributes of bridges is that they offer the possibility that someone may start to cross but never reach the other side. For that person the bridge is virtual; an open window that they can keep passing or climb through.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a landmark, a tourist attraction and a one-drop shop for suicides. Well-used, oft-chosen, perhaps “popular” isn’t the best choice of word. Some people say the bridge is haunted by past suicides; eerie shadows have been seen drifting across the vehicle deck.

There are no shadows today. And the only ghost on the bridge is flesh and blood. A woman, naked, standing outside the safety fence, with her back pressed to the metal lattice and wire strands. The heels of her red shoes are balancing on the edge.

Like a figure from a surrealist painting, her nakedness isn’t particularly shocking or even out of place. Standing upright, with a rigid grace, she stares at the water with the demeanor of someone who has detached herself from the world.

The officer in charge introduces himself. He’s in uniform: Sergeant Abernathy. I don’t catch his first name. A junior officer holds an umbrella over his head. Water streams off the dark nylon dome, falling on my shoes.

“What do you need?” asks Abernathy.

“A name.”

“We don’t have one. She won’t talk to us.”

“Has she said anything at all?”

“No.”

“She could be in shock. Where are her clothes?”

“We haven’t found them.”

I glance along the pedestrian walkway, which is enclosed by a fence topped with five strands of wire, making it difficult for anyone to climb over. The rain is so heavy I can barely see the far side of the bridge.

“How long has she been out there?”

“Best part of an hour.”

“Have you found a car?”

“We’re still looking.”

She most likely approached from the eastern side which is heavily wooded. Even if she stripped on the walkway dozens of drivers must have seen her. Why didn’t anyone stop her?

A large woman with short cropped hair, dyed black, interrupts the meeting. Her shoulders are rounded and her hands bunch in the pockets of a rain jacket hanging down to her knees. She’s huge. Square. And she’s wearing men’s shoes.

Abernathy stiffens. “What are you doing here, ma’am?”

“Just trying to get home, Sergeant. And don’t call me ma’am. I’m not the bloody Queen.”

She glances at the TV crews and press photographers who have gathered on a grassy ridge, setting up tripods and lights. Finally she turns to me.

“What are you shaking for, precious? I’m not that scary.”

“I’m sorry. I have Parkinson’s Disease.”

“Tough break. Does that mean you get a sticker?”

“A sticker?”

“Disabled parking. Lets you park almost anywhere. It’s almost as good as being a detective only we get to shoot people and drive fast.”

She’s obviously a more senior police officer than Abernathy.

She looks towards the bridge. “You’ll be fine, Doc, don’t be nervous.”

“I’m a professor, not a doctor.”

“Shame. You could be like Doctor Who and I could be your female sidekick. Tell me something, how do you think the Daleks managed to conquer so much of the universe when they couldn’t even climb stairs?”

“I guess it’s one of life’s great mysteries.”

“I got loads of them.”

A two-way radio is being threaded beneath my jacket and a reflective harness loops over my shoulders and clips at the front. The woman detective lights a cigarette and pinches a strand of tobacco from the tip of her tongue. Although not in charge of the operation, she’s so naturally dominant that the uniformed officers seem more ready to react to her every word.

“You want me to go with you?” she asks.

“I’ll be OK.”

“All right, tell Skinny Minnie I’ll buy her a low-fat muffin if she steps onto our side of the fence.”

“I’ll do that.”

Temporary barricades have blocked off both approaches to the bridge, which is deserted except for two ambulances and waiting paramedics. Motorists and spectators have gathered beneath umbrellas and coats. Some have scrambled up a grassy bank to get a better vantage point.

Rain bounces off the tarmac, exploding in miniature mushroom clouds before coursing through gutters and pouring off the edges of the bridge in a curtain of water.

Ducking under the barricades, I begin walking across the bridge. My hands are out of my pockets. My left arm refuses to swing. It does that sometimes—fails to get with the plan.

I can see the woman ahead of me. From a distance her skin had looked flawless, but now I notice that her thighs are crisscrossed with scratches and streaked with mud. Her pubic hair is a dark triangle: darker than her hair, which is woven into a loose plait that falls down the nape of her neck. There is something else—letters written on her stomach. A word. I can see it when she turns towards me.

SLUT.

Why the self-abuse? Why naked? This is public humiliation. Perhaps she had an affair and lost someone she loves. Now she wants to punish herself to prove she’s sorry. Or it could be a threat—the ultimate game of brinkmanship—“leave me and I’ll kill myself.”

No, this is too extreme. Too dangerous. Teenagers sometimes threaten self-harm in failing relationships. It’s a sign of emotional immaturity. This woman is in her late thirties or early forties with fleshy thighs and cellulite forming faint depressions on her buttocks and hips. I notice a scar. A cesarean. She’s a mother.

I am close to her now. A matter of feet and inches.

Her buttocks and back are pressed hard against the fence. Her left arm is wrapped around an upper strand of wire. The other fist is holding a mobile phone against her ear.

“Hello. My name is Joe. What’s yours?”

She doesn’t answer. Buffeted by a gust of wind, she seems to lose her balance and rock forward. The wire is cutting into the crook of her arm. She pulls herself back.

Her lips are moving. She’s talking to someone on the phone. I need her attention.

“Just tell me your name. That’s not so hard. You can call me Joe and I’ll call you…”

Wind pushes hair over her right eye. Only her left is visible.

A gnawing uncertainty expands in my stomach. Why the high heels? Has she been to a nightclub? It’s too late in the day. Is she drunk? Drugged? Ecstasy can cause psychosis. LSD. Ice, perhaps.

I catch snippets of her conversation.

“No. No. Please. No.”

“Who’s on the phone?” I ask.

“I will. I promise. I’ve done everything. Please don’t ask me…”

“Listen to me. You won’t want to do this.”

I glance down. More than two hundred feet below a fat-bellied boat nudges against the current, held by its engines. The swollen river claws at the gorse and hawthorn on the lower banks. A confetti of rubbish swirls on the surface: books, branches and plastic bottles.

“You must be cold. I have a blanket.”

Again she doesn’t answer. I need her to acknowledge me. A nod of the head or a single word of affirmation is enough. I need to know that she’s listening.

“Perhaps I could try to put it around your shoulders—just to keep you warm.”

Her head snaps towards me and she sways forward as if ready to let go. I pause in mid-stride.

“OK, I won’t come any closer. I’ll stay right here. Just tell me your name.”

She raises her face to the sky, blinking into the rain like a prisoner standing in a exercise yard, enjoying a brief moment of freedom.

“Whatever’s wrong, whatever has happened to you or has upset you, we can talk about it. I’m not taking the choice away from you. I just want to understand why.”

Her toes are dropping and she has to force herself up onto her heels to keep her balance. The lactic acid is building in her muscles. Her calves must be in agony.

“I have seen people jump,” I tell her. “You shouldn’t think it is a painless way of dying. I’ll tell you what happens. It will take less than three seconds to reach the water. By then you will be traveling at about seventy-five miles per hour. Your ribs will break and the jagged edges will puncture your internal organs. Sometimes the heart is compressed by the impact and tears away from the aorta so that your chest will fill with blood.”

Her gaze is now fixed on the water. I know she’s listening.

“Your arms and legs will survive intact but the cervical discs in your neck or the lumbar discs in your spine will most likely rupture. It will not be pretty. It will not be painless. Someone will have to pick you up. Someone will have to identify your body. Someone will be left behind.”

High in the air comes a booming sound. Rolling thunder. The air vibrates and the earth seems to tremble. Something is coming.

Her eyes have turned to mine.

“You don’t understand,” she whispers to me, lowering the phone. For the briefest of moments it dangles at the end of her fingers, as if trying to cling onto her and then tumbles away, disappearing into the void.

The air darkens and a half-formed image comes to mind—a gape-mouthed melting figure screaming in despair. Her buttocks are no longer pressing against the metal. Her arm is no longer wrapped around the wire.

She doesn’t fight gravity. Arms and legs do not flail or clutch at the air. She’s gone. Silently, dropping from view.

Everything seems to stop, as if the world has missed a heartbeat or been trapped in between the pulsations. Then everything begins moving again. Paramedics and police officers are dashing past me. People are screaming and crying. I turn away and walk back towards the barricades, wondering if this isn’t part of a dream.

They are gazing at where she fell. Asking the same question, or thinking it. Why didn’t I save her? Their eyes diminish me. I can’t look at them.

My left leg locks and I fall onto my hands and knees, staring into a black puddle. I pick myself up again and push through the crowd, ducking beneath the barricade.

Stumbling along the side of the road, I splash through a shallow drain, swatting away raindrops. Denuded trees reach across the sky, leaning towards me accusingly. Ditches gurgle and foam. The line of vehicles is an unmoving stream. I hear motorists talking to each other. One of them yells to me.

“Did she jump? What happened? When are they going to open the road?”

I keep walking, my gaze fixed furiously ahead, my left arm no longer swinging. Blood hums in my ears. Perhaps it was my face that made her do it. The Parkinson’s Mask, like cooling bronze. Did she see something or not see something?

Lurching towards the gutter, I lean over the safety rail and vomit until my stomach is empty.

There’s a guy on the bridge puking his guts out, on his knees, talking to a puddle like it’s listening. Breakfast. Lunch. Gone. If something round, brown and hairy comes up, I hope he swallows hard.

People are swarming across the bridge, staring over the side. They watched my angel fall. She was like a puppet whose strings had been cut, tumbling over and over, loose limbs and ligaments, naked as the day she was born.

I gave them a show; a high-wire act; a woman on the edge stepping into the void. Did you hear her mind breaking? Did you see the way the trees blurred behind her like a green waterfall? Time seemed to stop.

I reach into the back pocket of my jeans and draw out a steel comb, raking it through my hair, creating tiny tracks front to back, evenly spaced. I don’t take my eyes off the bridge. I press my forehead to the window and watch the swooping cables turned blue in the flashing lights.

Droplets are darting down the outside of the glass driven by gusts that rattle the panes. It’s getting dark. I wish I could see the water from here. Did she float or go straight to the bottom? How many bones were broken? Did her bowels empty the moment before she died?

The turret room is part of a Georgian house that belongs to an Arab who has gone away for the winter. A rich wanker dipped in oil. It used to be an old boardinghouse until he had it tarted up. It’s two streets back from Avon Gorge, which I can see over the rooftops from the turret room.

I wonder who he is—the man on the bridge? He came with the tall police constable and he walked with a strange limp, one arm sawing at the air while the other didn’t move from his side. A negotiator perhaps. A psychologist. Not a lover of heights.

He tried to talk her down but she wasn’t listening. She was listening to me. That’s the difference between a professional and a fucking amateur. I know how to open a mind. I can bend it or break it. I can close it down for the winter. I can fuck it in a thousand different ways.

I once worked with a guy called Hopper, a big redneck from Alabama, who used to puke at the sight of blood. He was a former marine and he was always telling us that the deadliest weapon in the world was a marine and his rifle. Unless he’s puking, of course.

Hopper had a hard-on for films and was always quoting from Full Metal Jacket—the Gunnery Sergeant Hartman character, who bellowed at recruits, calling them maggots and scumbags and pieces of amphibian shit.

Hopper wasn’t observant enough to be an interrogator. He was a bully, but that’s not enough. You’ve got to be smart. You’ve got to know people—what frightens them, how they think, what they cling to when they’re in trouble. You’ve got to watch and listen. People reveal themselves in a thousand different ways. In the clothes they wear, their shoes, their hands, their voices, the pauses and hesitations, the tics and gestures. Listen and see.

My eyes drift above the bridge to the pearl-gray clouds still crying for my angel. She did look beautiful when she fell, like a dove with a broken wing or a plump pigeon shot with an air rifle.

I used to shoot pigeons as a kid. Our neighbor, old Mr. Hewitt who lived across the fence, had a pigeon loft and used to race them. They were proper homing pigeons and he’d take them away on trips and let them go. I’d sit in my bedroom window and wait for them to come home. The silly old bastard couldn’t work out why so many of them didn’t make it.

I’m going to sleep well tonight. I have silenced one whore and sent a message to the others.

To the one…

She’ll come back just like a homing pigeon. And I’ll be waiting.

A muddy Land Rover pulls onto the verge, skidding slightly on the loose gravel. The woman detective I met on the bridge leans across and opens the pas

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...