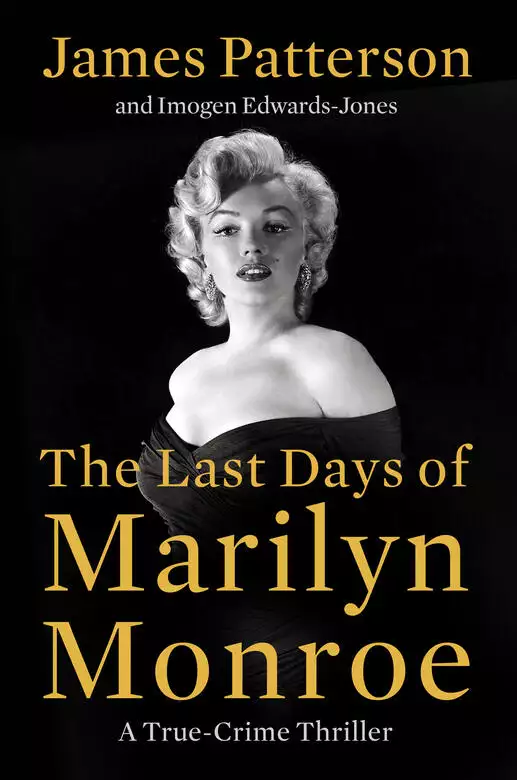

The Last Days of Marilyn Monroe

- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

With unparalleled ambition, instinctual physicality, keen business intelligence, and a remarkable sense of humor, Marilyn Monroe achieved sensational celebrity. Yet, she insisted, “I never really felt like a star. Not really, not in my heart.”

In the months before her death, Marilyn polishes the script for her ultimately unfinished film, Something’s Got to Give.

In the weeks before her death, she drinks champagne on Santa Monica Beach with the last photographer to take her picture.

In the days before her death, she's a guest of Frank Sinatra in the Celebrity Room at the Cal-Neva Lodge.

In the hours before her death, she argues with U.S. Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and his brother-in-law Peter Lawford.

In an emergency session with her psychiatrist, she confesses: “Here I am, the most beautiful woman in the world, and I do not have a date for Saturday night.”

On June 1, 2026, the world celebrates Marilyn Monroe’s 100th birthday. Without her.

In life, her superstardom defies classification.

In death, she remains shrouded in mystery.

The Last Days of Marilyn Monroe is a true crime thriller about a woman who changed Hollywood history, and whose indelible image captures our imagination to this day.

Release date: December 1, 2025

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Last Days of Marilyn Monroe

James Patterson

August 5, 1962

HOUSEKEEPER EUNICE MURRAY wakes suddenly, fear lodged in the pit of her stomach. It’s the middle of the night. She is worried, unsettled without knowing why.

It could be the stifling heat, or the cheap bedsheets that need changing. She gets out of bed, fumbling for her padded pink slippers and matching terry cloth dressing gown.

Opening her bedroom door, the housekeeper shuffles out into the vaulted hall of the home where she lives and works. The Spanish Colonial–style hacienda is tucked away at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive, a wooded cul-de-sac in Brentwood.

It belongs to her employer, movie star Marilyn Monroe.

Boxes are everywhere, half unpacked, the sideboard and spare chairs piled with papers and movie scripts. Unhung framed pictures sit on the floor, turned toward the wall to protect the glassed-in images.

The house is a relatively recent purchase, made on the advice of Marilyn’s psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson.

“Marilyn, you need to put down some roots,” he’d advised her. “Get yourself a house of your own.”

It’s true that after a childhood that included stints in eleven foster homes, two years in an orphanage, and a mother locked up in a mental asylum, Marilyn has always felt deprived of a real home.

So she had bought this house. But even after six months, she still hasn’t really moved in, hasn’t found the time to arrange things in the main house, much less the big backyard, the swimming pool, and the citrus grove. Half her furniture is still on order.

Mrs. Murray crosses the corridor to Marilyn’s bedroom. The door is shut, but the telephone cord wedged under the door attracts her attention. It’s the white telephone.

Marilyn has two lines. The white telephone is for personal calls. Marilyn often telephones her friends in the evenings, one after another. She lies in bed, cracks open a Nembutal capsule, adds a chloral hydrate tablet, drinks a champagne chaser, then gives them all a call. How she keeps track of what she says to whom, Mrs. Murray has no idea.

The other telephone, the pink one, is her general line, and it often rings during the night. Marilyn usually muffles the pink telephone and leaves it in the next room, smothering it under some cushions so it doesn’t wake her. She’s a light sleeper. An insomniac who’s obsessed with sleep.

It’s been over ten years since Marilyn has gone to bed without sedation. Barbiturates. Nembutal. Powerful drugs. Sometimes they make her forgetful. When she can’t remember if she’s taken the pills, she rolls over in bed, cracks open another bottle, and pops some more.

Mrs. Murray looks at the telephone cord again. Lamplight seeps out from the crack between the carpet and the door. She puts her ear to the door and listens. The silence concerns her. No giggles. No breathy whispers. Something isn’t right.

She tries the door handle, but the door is locked. That’s unexpected. Marilyn is fearful of locked doors. Her bedroom door is only locked when she’s with a gentleman friend. Tonight she went to bed alone.

Eunice tries again, but she can’t get the door opened. Starting to panic, she runs into the next room, throws the cushions off the pink telephone, and dials Dr. Greenson.

She knows the number by heart. Not only has Ralph Greenson been Marilyn’s personal psychiatrist for the past two years, he’s also the person who first hired Mrs. Murray to work with Marilyn. He treats Marilyn at home because she is too famous to visit his clinic. He lives nearby and was over to the house earlier that day.

The phone rings and rings.

“Come on!” begs Mrs. Murray, pulling her dressing gown tighter around her. “Pick up! Pick up…”

“Hello?” Dr. Greenson answers sleepily.

“It’s Marilyn,” she blurts. “Her door is locked. I can’t raise her.”

“Eunice?”

“Please…”

“I’m on my way.”

Marilyn’s bedroom overlooks the front lawn. Mrs. Murray hurries through the living room and out the front door. Along the way, she grabs a metal poker from the fireplace.

Outside on the lawn, she stops in front of Marilyn’s bedroom. Her light is on, but the curtains are drawn. One window is slightly ajar. Standing on her tiptoes, Mrs. Murray pushes the poker through the crack and jabs at the top of the curtains, edging one aside along the rail, exposing an eerie scene.

There she is.

Marilyn Monroe.

The most famous woman in the world.

“MEN DON’T SEE ME. They just lay their eyes on me.”

Mrs. Murray never understood what Marilyn meant by those words—until now. The housekeeper can’t scream, she can’t shout, she can only stare.

Has Marilyn overdosed again? Is she simply asleep? Or is she actually dead? There have been other nights Marilyn took too many pills. Times she’s been rushed to the hospital to have her stomach pumped, only to return, phoenix-like, hours later, like nothing had happened.

She looks so peaceful. Her eyes shut, her lips slightly parted. Lying on the bed. Naked. The alabaster skin. The bleached-blond hair in loose curls around the famous face. The sheets are wrapped around her calves. Her hand still clutches the telephone, which hangs off the hook.

The silence is oppressive. There’s no wind blowing through the trees, no cars driving this secluded lane. It feels like the world has stopped spinning. Surely, its brightest star, and its most photographed, cannot be dead at only thirty-six years old.

Where is Dr. Greenson?

The silence is broken by the high-pitched sound of Marilyn’s dog barking from the guest house. Maf normally sleeps in the main house. How did he get out?

Mrs. Murray listens to his anxious barking. Can the dog sense what’s going on?

A car comes screeching down Fifth Helena Drive. The front gate slides open and a man dressed in a dark suit and open-collared shirt—no time to put on a tie—runs across the lawn. “Is she breathing? Has she moved? Can you see her?”

Dr. Greenson sees the poker in Eunice’s hand. “Give me that,” he orders, using the tool to smash the bedroom window. The sound of shattering glass makes Maf bark even louder.

“I’m going in,” Dr. Greenson announces, swinging his leg over the windowsill. “Get Dr. Engelberg! I need to know what drugs he’s given her.”

Dr. Hyman Engelberg is Marilyn’s personal physician. He and Dr. Greenson have been coordinating Marilyn’s care.

Dr. Greenson hauls himself through the window and into the bedroom. He stops in his tracks at the bed, where Marilyn lies on her back. His patient, whom he adores. So beautiful. So young. So talented. The scene is almost too painful to witness.

He leans over her. He presses gently on the side of her slim white neck. Please, God, let there be a pulse. He presses harder. The flesh feels tepid, not as warm as he would like. Maybe there is something? There! A little…

Then he realizes his error. It’s his own pounding heartbeat that he feels.

“We’ve lost her!” he cries out, his knees buckling beneath him.

What to do? Who to call? An ambulance? The hospital? Where’s Engelberg?

The dog barks. Eunice weeps, removing her spectacles to dab her eyes with a handkerchief. Ralph Greenson has unlocked the door. His face is white with shock as he counts the pill bottles on the nightstand. Eight. Ten. Twelve. Some fifteen. All opened. There’s a trail of white pills scattered across the carpet, but there’s a fifty-capsule bottle of Nembutal that is completely empty.

Is this what she wanted? Greenson can’t believe it.

She was in a low mood when she called him yesterday evening. She complained about her personal life, she complained that she couldn’t sleep. But she wasn’t suicidal. He’s sure of that.

The front door slams. Running feet hammer across the terra-cotta tiles in the hall. “Where is she?!” demands Dr. Engelberg as he bursts through the bedroom door.

“Is she breathing? Have you checked for a pulse?” he asks Greenson, bending over. “Are you sure she’s not still alive?”

“She’s gone,” replies Greenson, with a slow shake of his head.

Dr. Engelberg inserts the earpieces of his stethoscope and places the instrument on Marilyn’s chest to listen for breathing sounds. He pauses. He then checks the pulse points at her wrists and listens to her lungs.

“There’s no sign of foul play, no blood or wound,” he declares, examining the body. “But she is gone. Most certainly.” He sighs, removes his stethoscope, and picks up the empty bottle of Nembutal.

The customary dose is one tablet per night.

“I gave her that prescription only three days ago,” Engelberg says. “And only after she begged me.”

“I thought we agreed that we were weaning her off medication?” Greenson raises his voice for emphasis. “That’s what we said. No more drugs. No more. Enough.”

“We had,” acknowledges Engelberg. “And we were doing well. I’d got her usage right down. Until her last appointment when she wouldn’t let me leave without prescribing fifty capsules.” He starts picking up the bottles on the nightstand, his eyes scanning the labels. “Chloral hydrate. Jesus,” he whispers. “Knockout drops… Where did she get fifteen bottles of medicine?”

“I thought it was you,” Greenson says, glaring at Engelberg.

“Me? No. I’d never prescribe that. Mix it with alcohol and Nembutal…” He looks down at Marilyn on the bed and checks the empty bottle again.

“Fifty…” He shakes his head. “I think we should cover her up, don’t you? Or at least roll her onto her front?” He looks around the sparsely furnished and frankly inelegant room of the world’s most famous movie star. “Give the place a little decorum.”

“I can’t face it,” Greenson replies, his voice barely audible, “but shouldn’t we call the police?”

It is 4:25 a.m. when Engelberg makes the call.

“MARILYN MONROE HAS DIED. She’s committed suicide.”

Sergeant Jack Clemmons is a homicide investigator with the Los Angeles Police Department. He immediately presumes the call is a hoax. Drunks call the police department, making ridiculous claims, at every hour of the day.

“Who did you say was calling?” he asks.

“I’m Dr. Hyman Engelberg, Marilyn Monroe’s physician. I’m at her residence. She’s committed suicide.”

“I’ll come right away.”

It is almost 5 a.m. when Sergeant Clemmons arrives. He’s already radioed for backup. He hopes they won’t be long. It’s never pleasant attending a suicide.

The one-story bungalow with a tiny front yard is smaller than he expected. Don’t they make millions in Hollywood? He knocks on the front door.

It takes a while for someone to answer. Weren’t they expecting him? He can hear the constant yapping of a dog. And from the inside, whispering and shuffling sounds.

Finally, an elderly woman answers. She’s neatly dressed in a maroon skirt and a buttoned-up baby-blue cardigan.

“Sergeant Clemmons.”

“Eunice Murray,” she replies, smiling briefly. “I am Marilyn Monroe’s housekeeper. Or I was… She’s committed suicide.”

“She has?”

“I found her. Lying on her bed, naked, still holding the telephone. It was the telephone cord that first alerted me,” she continues in an odd monotone. “I woke and left my bedroom,” she indicates across the corridor. “And I saw the cord and the light under the door.”

“What time was this?”

“Three a.m. I remember it as I looked at my watch.” She lifts her wrist by way of demonstration. “Over here.”

He follows Mrs. Murray through the hall.

She points toward the open bedroom door. “Forgive me if I don’t come in. But I have a lot to do.”

In the half-lit bedroom, Clemmons finds two men, who introduce themselves as Marilyn Monroe’s attending physicians. Dr. Greenson sits with his head in his hands, while Dr. Engelberg paces the cream-colored carpet. He glances at the broken window and the pinking dawn, like he is waiting for something.

Clemmons surveys the small bedroom. There’s no glamorous padded headboard, no glittering chandelier, none of the spoils of stardom. There are pills and handbags and clothes on the floor, which is now also covered with shattered glass. He looks down at the bed. Marilyn’s body is covered in a sheet. She is lying on her front. One arm hangs off the bed, her hand in a claw. Her unpolished fingernails are bitten to the quick.

This isn’t right. Clemmons furrows his brow. Marilyn’s legs are perfectly straight. Her face is buried in a pillow. He’d like to get a look at her mouth, check for signs of foam or vomit. Suicides are usually messier than this. The normal signs of distress or struggle are not present.

“Where’s the drinking glass?”

“The what?” replies Dr. Engelberg.

“Her glass of water.” Clemmons nods toward the nightstand. “If you’re going to take a lot of pills, you need a lot of water.”

“I don’t know,” Dr. Engelberg sounds irritated. “Maybe the housekeeper does.”

“So, this is not the crime scene?” The sergeant looks from one doctor to another.

“It is,” declares Dr. Engelberg. “But there’s no crime.”

“So, where’s the glass?”

“There wasn’t one,” says Greenson. “Not when I broke in through the window anyway.”

“No glass,” confirms Clemmons, taking out his notepad.

“Not that I saw,” says Dr. Greenson. “But then I wasn’t really looking. I was more worried about, um, the patient.”

“You broke in?” asks Clemmons.

“Through that window.” Dr. Greenson glances over his shoulder at the shattered windowpane.

“And did you try to revive her?”

“It was too late,” replies Dr. Engelberg.

“We were all too late,” adds Greenson.

“Do you have any idea when she took the pills?” Neither doctor meets his eye.

“No,” they both reply.

“Do you mind if I take a look?” he asks, indicating the bed.

“Go ahead,” replies Dr. Engelberg.

Clemmons pulls back the sheet. There are the distinctive blond curls, the smooth curves of her shoulders, the luminous white skin of her back. He pauses. It feels almost indecent to carry on. There’s a slight purple discoloration over her buttocks. Her smooth legs are aligned, her toes turned inward. She has a dried-up blister on her left foot. He covers her quickly. It feels intrusive.

“Any idea who she was calling?” he asks.

“Calling?” Dr. Engelberg looks surprised.

“The housekeeper says she was holding the telephone?”

“Oh? Did she? Maybe she realized what she had done and was calling for help?”

“But the housekeeper’s bedroom is less than ten feet away. Why wouldn’t she just shout out?”

There’s another knock at the front door. This is my case now, Clemmons thinks as he strides to answer it, determined not to leave the two doctors alone at the scene any longer than necessary.

“Who are you?” asks the sergeant.

Standing on the doorstep is a scrawny young man with a small chin and a large Adam’s apple, dressed in workman’s dungarees and carrying a toolbox.

“Norman. Norman Jeffries. I came as quickly as I could. My mother-in-law called and asked me to come and fix a broken window.”

“Your mother-in-law?”

“He’s married to my daughter,” Mrs. Murray says. “He does all the odd jobs around the house.”

“And you called him?” Clemmons is astonished. Who comes to mend a broken window at 5:15 in the morning?

“He lives locally. And it needs to be done.” Eunice looks at the detective. “It’s dangerous.”

Clemmons takes a step back to allow the handyman in.

“There are newsmen outside the house,” Jeffries tells the sergeant. “And a few of the neighbors.”

“Newsmen?” asks Clemmons.

“That’s right,” he confirms. “They asked what I was doing here. I said I was here to fix a broken window. Has something happened?”

Was his call for backup intercepted?

“How many people are outside?” asks Clemmons.

“Twenty, thirty,” replies the handyman. “I didn’t stop to count.”

THE SECRET IS OUT. Hollywood’s screen goddess is dead.

Sergeant Clemmons’s radio call was overheard and beamed around the world. Newspaper editors are waking their reporters, demanding that they get over to Brentwood. Time, Life, and the New York Herald Tribune already have writers stationed outside Marilyn Monroe’s gate.

More reporters arrive. Cameras. Lights. News trucks park up along Fifth Helena Drive.

Inside, the police set up an office in the kitchen as more officers join the investigation. A police photographer documents Marilyn’s bedroom, popping off flashbulbs.

Marilyn’s lawyer, Milton “Mickey” Rudin, marches in, as does her personal publicist, Pat Newcomb.

“This must have been an accident,” Newcomb says, but she is overcome with grief and quickly dissolves into sobs. “When your best friend kills herself, how do you feel? What do you do?”

In the chaos, a gossip columnist manages to get into the house and take photos of Marilyn lying dead on the bed. Pretending to be from the coroner’s office, he’s only removed when the real team arrives at about 5:45 a.m. The mortuary van navigates the crowds, barely clearing the gate.

Everyone wants a glimpse. A glimpse of what? The body? A curl of blond hair hanging off the back of the stretcher?

Guy Hockett, director of Westwood Village Mortuary, walks into the bedroom along with his son, Don. The younger Hockett has been working with his father to earn money for a trip to Mexico at Christmas. Together, they begin to pick up some of the drugs and place them in plastic evidence bags.

Next, it’s the body. This is only Don’s third corpse. The first two, both elderly men, didn’t bother him much. But this is Marilyn Monroe, and he can’t bear to look.

“Get the gurney, son,” says his father, sensing Don’s discomfort. “I can deal with this.”

Don walks back through the house packed with police officers and doctors all talking over each other. He walks past the housekeeper doing the washing and goes out into the front yard. He pulls the gurney out of the back of the van and sets it up on its wheels. It’s old and stained. It doesn’t seem good enough for her.

By the time Don returns to the bedroom, his father has prepared the body. Marilyn’s arms are crossed over her chest and she’s covered in a pale blue blanket. Together they lift the corpse and use two leather straps to secure it on the gurney.

Dr. Engelberg accompanies the somber procession. At the entrance to the house, they pause. The young man straightens the blanket. The doctor looks down at tiles set into a flagstone. One bears a small coat of arms and two words in Latin.

“Cursum Perficio,” he says, then translates the inscription: “My journey’s end.” He sighs as he watches father and son wheel the gurney toward the van. “Oh, Marilyn. Dear, dear Marilyn.”

“So, I have fixed the window,” announces Norman Jeffries, holding his toolbox. “I think I’ll be off then. Nothing more for me to do here.”

The bewildered doctor is not really listening. He watches the van disappear through the gate to the explosion of a thousand flashbulbs.

“I can take the dog if you want,” Jeffries says, nodding over at the guest house. “Poor little thing hasn’t stopped barking. I wonder if he knows his mistress is gone.”

Maf’s stuffed toys, a tiger and a lamb, are strewn across the backyard.

As Engelberg gathers up his things, he watches Mrs. Murray walk across the front lawn toward where Life magazine entertainment correspondent Tommy Thompson is waiting outside, his microphone at the ready.

“She was nude… totally nude when I found her,” Mrs. Murray begins, “lying in bed, clutching her white telephone. Her bedroom light was on and the telephone cable under the door alerted me…”

Eunice Murray would stick to her story, but everyone who crossed the threshold that night would say something different.

How do you go about writing a life story? Marilyn once asked a journalist. Because the true things rarely get into circulation. It’s usually the false things. It’s hard to know where to start if you don’t start with the truth.

But nobody was interested in that.

HER BUST IS the first thing her classmates notice. What the hell happened to Norma Jeane the Human Bean over the long, hot summer of 1939?

Thirty or so students at Ralph Waldo Emerson Junior High School watch, open-mouthed, as thirteen-year-old Norma Jeane Mortenson rushes into morning math class in Westwood, California. A whirling dervish of books, auburn curls, and a tight sweater.

She’s late. She’s always late.

Without a nickel for bus fare, it’s more than a two-mile walk from Sawtelle, where no one who’s anyone lives, to the school in prosperous Westwood. Norma Jeane never has a nickel, so every school day she walks the nearly five-mile round trip there and back to the intersection of Corinth and 11348 Nebraska Avenue.

Come rain or shine, she always walks alone, singing as she goes down the road, or in the school corridors, or on her way to the lunchroom. She sings, “Jesus loves me, this I know,” which is lucky, because no one else loves her.

Norma Jeane boards with Ana Lower, who she calls “Auntie” Ana. But Ana is no real relation; she is the aunt of Norma Jeane’s legal guardian, Grace McKee Goddard.

Grace is her mother’s best friend, and has been watching out for Norma Jeane since she was born on June 1, 1926, in the charity ward of Los Angeles General Hospital. When Norma Jeane’s mother, Gladys Monroe Baker, was institutionalized in 1934, she signed her daughter’s care over to Grace—and now Grace has passed the teenager on to Auntie Ana, a safe spot after years spent shuttling between foster homes and the orphanage.

Like Grace and Gladys, white-haired Auntie Ana is a devout Christian Scientist. As a local landlord and a church advisor, Ana is compassionate yet practical. She tries to teach the thirteen-year-old about sex. Warn her.

The lesson comes just in time. On the first day of school that year, Norma Jeane discovers that she has outgrown her two county-issued dresses. She goes next door to borrow a little blue sweater. And it is a little too little, and too blue, and the whole class can see the bounteous gifts that Mother Nature has bestowed on the formerly skinny waif.

When I walk into the classroom, Norma Jeane realizes, the boys suddenly begin screaming and moaning and throwing themselves on the floor.

At recess, Norma Jeane is surrounded. There are six boys, all of them smiling.

“What happened to you?” asks one freckle-faced jock, his hand cupping his chin as he looks her up and down. “You’ve gone from String Bean to hubba-hubba in one summer.”

“Hmm,” purrs Norma Jeane. The buzzing “hmm” noise is the one all the girls at school make to sound like Jean Harlow in the movies.

The other kids in her class used to whisper. They pointed their fingers and crossed to the other side of the street. No one wanted to be seen with the girl who stuttered when she spoke and dressed in clothing from the Los Angeles Orphans’ Home Society. No one wanted to be friends with the girl whose mother is institutionalized. No one wanted to invite Norma Jeane home after school.

Now the boys are much more attentive.

“You’re the Hubba-Hubba, Hmm Girl, that’s what you are.”

The boy’s voice isn’t teasing. He’s paying her a compliment, which might be the very first she’s ever had. Norma Jeane doesn’t quite know how to react, so she smiles sweetly and bobs a little curtsy.

“Why thank you, sir.”

Norma Jeane is excited to tell Aunt Ana the news. “They know my name now. I’m no longer the Orphan,” she says, breaking into an imitation of her schoolmates’ taunts—‘Orphan 3463 with no friends and a mumma in the madhouse.’” She smiles. “The world is a much friendlier place now that I’m the Hubba-Hubba, Hmm Girl.”

When Norma Jeane finds some old ruby lipstick and a pencil to darken her brows, the world gets even friendlier. Drivers honk their car horns when they pass her on the way to Westwood and every boy wants to walk her home from school.

Her stutter begins to disappear.

She chooses a boyfriend. He’s more than old enough to know better, but maybe he doesn’t care that the girl sitting in his passenger seat, laughing at his bad jokes, is only thirteen years old.

Norma Jeane and her new boyfriend drive to the beach. It’s a beautiful day for a stroll on the sand overlooking the largest and deepest ocean on earth.

She’s been practicing a new walk, a sophisticated, languid movement with pointed toes and swinging shoulders. Point and swish. Point and swish. Just like the divas on the silver screen.

“Shall we dive in?” asks her beau.

“In the ocean?”

“Of course, the ocean,” he laughs as he strips off his shirt and shorts and runs toward the foam.

Norma Jeane peels off . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...