- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

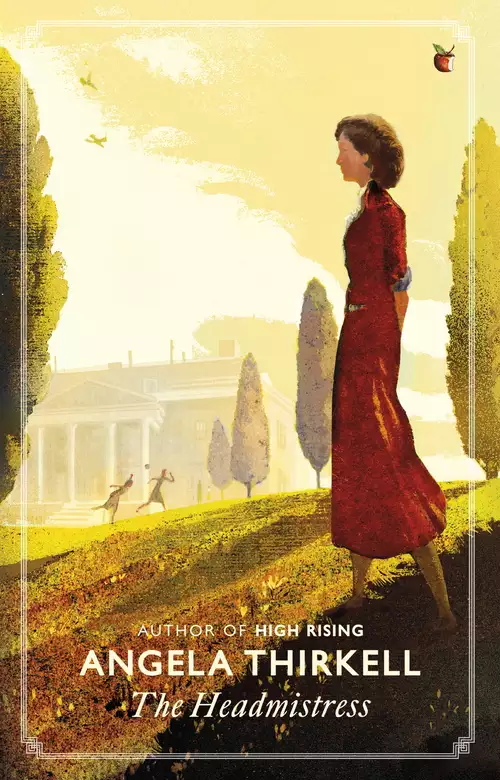

Synopsis

Barsetshire in the latter years of the Second World War is a peaceful and gossipy place, but there has been one lively change. A girls' school, evacuated from London, has taken over Harefield Park. Miss Sparling seems to be the perfect headmistress: she dresses as a headmistress should and is an easy and erudite conversationalist. Her new neighbours like her and her pupils respect her, but there is something missing from her life; something which - though she never dreamt it when she arrived - perhaps Barsetshire can provide...

Release date: November 17, 2016

Publisher: Virago

Print pages: 298

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Headmistress

Angela Thirkell

But gentleman-farming is no inheritance and by the time the war settled down upon the world the Beltons were living on overdrafts to an extent that even they found alarming, and two years later were unhappily making up their minds to sell a house and estate for which there would probably be no demand, when Providence kindly intervened, in the shape of the Hosiers’ Girls’ Foundation School. This old and very wealthy city company supported two excellent schools. The boys’ school had been evacuated at the beginning of the war to Southbridge, but was now back in London. The girls’ school had gone to Barchester and had a working arrangement with the Barchester High School. Their school buildings in London had been almost completely demolished in 1940, so they remained in Barchester. Their parents, who were mostly doing pretty well, were so glad to find their daughters healthy and happy that when they had also realized the great joy of only seeing them in the holidays, instead of five days in the week from half-past four in the afternoon to nine o’clock in the morning, not to speak of all Saturday and Sunday, most of them gladly agreed to their remaining as boarders.

If this decision had been made earlier in the war it would have been easier to find a house, but now, what with Government offices, insurance companies (which had an insatiable appetite for country mansions), banks, hospitals and the Forces, there was not a good house available in the district. Miss Sparling the headmistress spent all her weekends looking at impossible places and grew more and more anxious. Not only did she wish to please her employers, with whom she was on excellent terms, but her heart sank at the thought of another year, nay even another term, in Barchester. Not that she was unpopular. The Close had taken her to its bosom and the professional families much enjoyed her company, but she was not happy. Soon after the Hosiers’ Girls came to Barchester Miss Pettinger, the headmistress of the Barchester High School, had very graciously pressed Miss Sparling to stay with her. Miss Sparling, worn out by a succession of rooms and landladies each more repellent than the last, had gratefully accepted this invitation and eternally regretted that she had done so. It was not that she was starved, or beaten, or given an iron bedstead with a thin mattress, or made to sit below the salt, but there was something about Miss Pettinger that made her whole life acutely uncomfortable. What it had meant to be at close quarters with Miss Pettinger for two years, only Miss Sparling knew, though many of Miss Pettinger’s ex-pupils could have voiced her feelings; notably Mrs Noel Merton, now living at her old home near Northbridge, who went so far as to remark to Miss Lavinia Merton, aged six months, that if she didn’t hush her, hush her and not fret her, that old beast Pettinger would in all probability get her.

Then, one Sunday afternoon at the Deanery, the Archdeacon’s wife from Plumstead happened to mention that Lady Pomfret had told her that she heard the Beltons were going to try to let the Park. Miss Sparling, always with the welfare of her school at heart and spurred by the ever-springing hope of getting away from Miss Pettinger’s society, rang up her employers that night. Within forty-eight hours the Hosiers’ solicitor had telephoned to Mr Belton, come down to Barchester with a surveyor in his train, extracted a car and petrol from the Old Cathedral Garage, seen Mr Belton’s lawyer, been all over the house with Miss Sparling and the surveyor, and gone back to London. Within a fortnight the Beltons had moved into the village, workmen had been produced, the necessary alterations made, and by the beginning of the autumn term Miss Sparling was installed at Harefield Park with her staff, her girls, and a delightful little suite of her own in the West Pavilion. No longer would she have to listen to Miss Pettinger’s views on politics or her account of her motor trip in Dalmatia; no longer would she be cross-examined as to the probable results of her girls in the School Certificate examination; no longer would she have to hear herself introduced with a bright laugh as ‘my evacuee, but so different, quite an old friend now’; no longer – but when she came to think about it, she could not honestly say that Miss Pettinger had ever been spiteful, ungenerous or unkind in word or deed. It was only that she simply could not abide that lady; and here again Mrs Noel Merton would have entirely agreed with her.

Most luckily Arcot House, a small but handsome house in the village belonging to Mr Belton, fell vacant about this time, owing to the death of old Mrs Admiral Ellangowan-Hornby. That lady, the daughter of a Scotch peer, had a taste for white walls, good furniture and ferocious cleanliness, so when her heir, a nephew who did not in the least wish to live there, suggested that the owners might like to take it furnished, very little was needed in the way of preparation, and a few days before school reassembled Mr and Mrs Belton, who had been living at the Nabob’s Head at the upper end of the village, walked quietly down the High Street and entered Arcot House. In the drawing-room, which commanded the village street in front and the garden with a distant view of Harefield Park at the back, a bright fire was burning, the furniture caught the gleam of the flames, Mrs Admiral Ellangowan-Hornby’s Scotch ancestors and ancestresses looked down with immense character from the walls, and tea was laid. A tall, plain, middle-aged woman who looked like a cross between a nurse and a housekeeper, as indeed she was, came in with a kettle and set it down by the fire.

‘That’s in case you wanted any more hot water, madam,’ she said. ‘And Mr Freddy telephoned to say he’d be here any time, and Miss Elsa telephoned to say she might turn up tonight or tomorrow morning, and Mr Charles did ring up but I couldn’t hear what he said, but Gertie Pilson at the exchange says if he rings up again she’ll take the message herself. I’ve got all the beds ready and Hurdles says he’ll see there’s a nice bit of meat if it’s for the Commander and I was to tell you he’ll get you something nice off the ration if Miss Elsa comes and Pratt’s got some lovely kippers Mr Charles can have for his breakfast. I lighted the fire and there’s enough coal in the old lady’s cellars to last six months and plenty of wood in the park so don’t you worry.’

Having issued these orders of the day, the woman turned on her heel and left the room, not exactly slamming the door, but shutting it with a degree of firmness which anyone unaccustomed to her ways might have taken as a sign of ill-temper. Her master and mistress (by courtesy), who were used to her ways, remained unmoved. When Mrs Belton was engaging a nurse before the birth of her first child, a young woman had applied for the post who was so obviously the right person to rule a nursery that young Mrs Belton had engaged her almost without inquiry. Her family was well known and respected in Harefield, her uncle Sid Wheeler being landlord of the Nabob, her cousin Bill Wheeler a first-class chimney sweep and the only person who really understood the chimneys at Pomfret Towers, and her mother an excellent laundress. Her father chiefly lived on his wife, supplemented with odd jobs, but as Harefield, like many villages, was at bottom matriarchal, no one thought much the worse of him. When asked her name the young woman had said Wheeler; and on being pressed had grudgingly admitted to S. Wheeler, adding that she was properly christened and didn’t wish to say no more, and such was her strength of character that no one had ever dared to call her by anything but her surname.

Mr Carton, whose interest in genealogies and families boiled over in every possible direction, had given it as his opinion after spending several evenings at the Old Begum, an alehouse patronized by Mr Wheeler père, that her dislike of her name being known, while largely based on a fine primitive feeling that by letting your name be known you gave unknown powers a handle over you, was also due to a class feeling that upper servants, such as butlers and head parlourmaids, were always called by their surname and one was not going to demean oneself before such. Therefore into the nursery she had come as Wheeler, and Wheeler she had remained. By such interfering and inquisitorial visitations as censuses and later identity cards and ration books, not to speak of her mother when she brought the personal wash up to the Park, or general conversation in the village, it had long been known that her name was Sarah, but no one had ever dared to use it. Even Charles Belton, her latest and best-loved nursling, had only once, flown with a century made for Harefield v. Pomfret Madrigal on the home ground, attempted to call her Sarah and had been so awfully set down in the tea marquee, in front of both teams, that he had never tried again.

‘Why so many cups and saucers, do you suppose, Lucy?’ said Mr Belton, who had been studying the tea equipage in silence.

His wife looked at the table, where six or seven cups, saucers and plates of delicate china were set out.

‘I can’t think,’ she said. ‘But I’m very glad Wheeler is going to be our houseparlourmaid. Anyone else would break that china at once, and Mrs Ellangowan-Hornby’s nephew might go to law about it, for we could never replace it and it’s probably worth a million pounds. Come and have your tea, Fred, and use one of them. How funny it is to be living in someone else’s house.’

‘Only leasehold. My house if you come to think of it,’ said Mr Belton, who held strong views about property, though a very long-suffering landlord with his small tenants. ‘My house twice over if it comes to that. Property belongs to me and I’m tenant of the old lady’s nephew as well.’

‘I wonder what Captain Hornby is like,’ said Mrs Belton, sitting down at Captain Hornby’s table, in his chair, and beginning to pour out tea from his teapot.

‘Like?’ said her husband. ‘Like anyone else I suppose. Where’s my saccharine? Where is my saccharine? Damn the filthy stuff. Can’t think why old What’s-his-name in Harley Street told me to take it. Partner in a saccharine factory probably. That’s the way all these doctors live.’

Mrs Belton gently pushed towards her husband the little silver box in which his saccharine was kept. She did not answer, because she knew his gruffness was merely a screen for a wounded pride. He had been as good as gold about leaving his family home, for he had the courage to face disagreeable facts, but his wife knew how deeply he felt it that the inevitable blow had fallen in his lifetime and how, in spite of valiant efforts, he could not help feeling that he had come down in the world. For five generations the Beltons had sat in their Palladian mansion looking over their own parkland. Now the sixth Belton since the nabob was sitting in a drawing-room, a parlour, in a house in the village street, a house which, except for the lucky fact of its being up four steps from the pavement with rather terrifying barred basement windows looking on to tiny areas with a grating over them, would have had to have blinds in the front rooms to prevent passers-by looking in. Mrs Belton was a humble creature in some ways but her pride too was wounded, for she knew she had brought her husband little dowry. A Thorne, one of the many cousins of the very old Barsetshire family at Ullathorne, she was of good blood, but no amount of blood could keep Harefield Park from turning into a girls’ school. In happier days she had hoped that in her children the family might at last come into its proper place again. Freddy was to marry a very rich delightful heiress and put proper bathrooms all over the house when his father died and he left the Navy and came into the place, Charles was to make an immense fortune in business, be a kind wealthy bachelor uncle and leave all his money to Freddy’s children, and Elsa was to marry very well, preferably the heir to a dukedom or at least a marquisate, and present Freddy’s girls at court. These things would surely come to pass with children as good-looking, gifted and charming as her own; and if Freddy and his wife wanted to live at Harefield Park, why his parents could well retire to one of their houses in the village and let the young people have their fling. But to retire in favour of a girls’ school, to confess oneself beaten by one’s own estate, to take away from one’s children the home of their childhood, the nursery where they had quarrelled, the kitchen where they had teased the cook, the disused hay lofts in the stables where they had played, the lake where they had muddily bathed in summer and dangerously (for there was a very cold spring in the middle of it) skated in winter, these were very bitter thoughts, and Mrs Belton’s pretty, anxious face was contorted by the unbecoming grimaces one makes to show that one has no intention of crying; no, not the least idea in the world.

‘What is the matter, Lucy?’ said Mr Belton, almost glad to turn upon his wife as a relief from the very similar feelings that were tearing him. ‘I mean, my dear, is anything really the matter?’ he added in a more gentle voice.

His wife would have found it almost easier to deal with his more truculent mood, but so touched was she by his effort to be sympathetic that she gulped down all her unhappiness and said,

‘I was only wondering if the children would be allowed to skate this winter if they get leave.’

‘Allowed? What the devil do you mean allowed?’ said Mr Belton. ‘We haven’t sold the whole place, my dear, only let the house and garden. That Miss Sterling —’

‘Sparling,’ said his wife.

‘Sparling then,’ said Mr Belton, ‘though it’s a name I don’t know, queer sort of name, seems a nice sort of woman. It was her idea that we should keep the East Pavilion. And to tell the truth, if I’d had to move the estate office it would have been very inconvenient. I couldn’t very well see the tenants here. And this is a good house, Lucy. Old Dr Perry, not this man, his father, always said it was the best house in the High Street. I’m sorry, Lucy, I’m sorry.’

So noble did Mrs Belton think her husband for confessing, or at any rate recognizing, his fit of temper that she felt more like crying than ever, when a loud peal distracted her.

‘Damn that bell,’ exclaimed Mr Belton, glad of a legitimate excuse for working off his feelings. ‘It’s been like that for twenty years. One touch and it rings like a fire engine. The old lady complained more than once and Icken has been down to see it again and again. He’s the best estate carpenter in the county, but he couldn’t get the damned thing right. What is it, Wheeler?’

‘It’s the Vicar, sir,’ said Wheeler. ‘He says to say if you are tired he won’t come in. And Lady Graham has sent two rabbits and a basket of mushrooms by the coal man, madam, with her love and you must let her know if there’s anything she can do.’

‘How kind of dear Agnes,’ said Mrs Belton. ‘Yes, of course we want to see Mr Oriel, Wheeler.’

Wheeler retired and came back with the Vicar whom, quite apart from his collar and black vest, anyone would have known for a clergyman at once on account of his large and flexible Adam’s apple, which fascinated the rash beholder’s eye and had once caused Charles Belton, aged four, to ask him why he couldn’t swallow it.

‘How very nice of you to come, Mr Oriel,’ said Mrs Belton getting up. ‘Have you had tea?’

‘But you are expecting a party,’ said Mr Oriel, looking nervously at the array of china.

‘That was our faithful Wheeler,’ said Mrs Belton, ‘and why all that crockery I can’t think. But we aren’t expecting anyone and are so delighted to have you as our first guest.’

‘I confess I am relieved,’ said Mr Oriel, shaking hands with Mr Belton. ‘I saw Lady Pomfret’s lorry outside the Town Hall and made sure she would be here. Milk if you can spare it; no, no sugar thanks. I have a small bottle of saccharine tablets which I carry about in my pocket,’ said the Vicar, feeling with every hand in every pocket.

‘Have some of mine,’ said Mr Belton, opening the little silver box, ‘filthy stuff.’

‘It seems ungrateful to say so, but it is,’ said the Vicar, obviously relieved, ‘and why we take it I cannot think.’

‘Instead of sugar. And a damn silly thing to do,’ said Mr Belton. ‘Stuff isn’t sweet, it’s bitter. And the more you put in the nastier it is.’

‘I never did take sugar in my tea, or in coffee,’ said the Vicar. ‘I have always disliked it. But I understood that by taking saccharine, we were somehow assisting the war effort. There are so many ways of helping the war and one sometimes finds them a little bewildering. Now, we were told that His Majesty has only five inches of water in his bath, so of course I marked a five-inch line on the Vicarage bath – and I cannot tell you how difficult it was, for as you know there is no corner in a bath, no square corner if I make myself clear, by which you can really judge. If you put a ruler against the side of the bath it is all so round and slanting, the bath I mean,, that you cannot tell exactly where the mark should come. But I had an inspiration. I filled the bath rather full and stood a ruler upright with its low end, I mean the one where it says one inch, resting on the middle of the bottom. I then pulled out the plug, and when the water had dropped to the figure five, I put it in again. While I was putting it in a little more water ran away, but this made it about fair, for as you know there is on many rulers, and on the particular ruler in question, a little bit at the beginning, or rather at each end, which is not included in the inches, which would have given me an unfair advantage.’

‘Some cake,’ said Mrs Belton sympathetically.

‘But now – oh, thank you,’ said the Vicar, helping himself to a slice, ‘I am again in a quandary.’

‘I don’t see why,’ said Mrs Belton. ‘You’ve got your five inches.’

‘Yes; but here is the rub,’ said the Vicar. ‘If, in error, I fill the bath up to the five-inch mark with boiling water, for my housekeeper keeps the water delightfully hot, is it fair to add sufficient cold water to make it bearable?’

‘You’d be boiled like a lobster if you didn’t, Oriel,’ said Mr Belton. ‘I can’t think why we never had cake like this at home, Lucy. Reminds me of my tuck-box at my first school.’

‘That is exactly what I meant,’ said the Vicar, gratified that he had made himself so clear. ‘So, even at the risk of disloyalty, I have to add cold water, which does not of course increase my own fuel consumption, but does, so I am told, increase the fuel consumption wherever it is that the cold water has to be pumped from. And then again if I put my cold water in first —’

‘Which you always ought to,’ said Mrs Belton earnestly. ‘That is the first thing any good nannie has to learn, or she may scald the baby when she puts it in.’

‘— I may put in too much and so be obliged to fill up with so much boiling water that it comes well above the five-inch mark. How very good this cake is.’

‘Well, Oriel, I wouldn’t worry too much if I were you,’ said Mr Belton. ‘There’s that bell again.’

Another violent peal resounded from basement to attic. Wheeler appeared.

‘It’s Lady Pomfret, madam,’ she said. ‘She says to say if you’re too busy. And I forgot to tell you, Mrs Brandon brought the cake when she came over to see about the Land Girls. She says it is real flour she had hoarded, not this nasty healthy stuff, and if she can do anything please let her know and Mrs Hilary’s new baby is a dear little girl.’

‘But of course ask Lady Pomfret to come in,’ said Mrs Belton, for she was very fond of the young countess whose mother-in-law had been a distant Thorne cousin. So in came Lady Pomfret with Lord Mellings aged four and a half and Lady Emily Foster aged three.

‘Dear Lucy, how very delightful to find you,’ said Lady Pomfret. ‘The home farm lorry was going to Northbridge, so the children and I came in it and it is going to pick us up in half an hour. What a beautiful room, Mr Belton. I have never been in this house before.’

‘Do you know our Vicar, Mr Oriel?’ said Mrs Belton.

‘I have not had the pleasure of meeting you before, Lady Pomfret,’ said Mr Oriel, ‘but I knew your dear mother-in-law well. In fact we were some kind of connection, but it always puzzles me.’

‘Let’s see, Lady Pomfret was a – bless my soul, what was she?’ said Mr Belton. ‘I know as well as I know my own name, but it is just where I can’t get at it.’

‘She was Edith Thorne, Fred,’ said his wife. ‘I didn’t know you had Thorne relations, Mr Oriel. We must have been cousins all these years without knowing it.’

‘It is hardly so near as that, I am afraid,’ said Mr Oriel smiling. ‘The connection is through the Greshams.’

‘Wait a bit now,’ said Mr Belton, as if Mr Oriel were trying to take an unfair advantage. ‘There was a bit of a scandal, wasn’t there? Something about a queer – if that bell rings again, Lucy, I’ll have Icken down tomorrow to dismantle the whole thing and have an electric one. What is it, Wheeler?’

‘Mr Carton’s called and he says if you are busy he won’t come in,’ said Wheeler. ‘And Miss Marling brought some grapes and a brace of partridges, madam, with Mr Marling’s love. Miss Marling was in the pony-cart and said she couldn’t stop, but if you wanted a small load of manure she could tell you where to get some. Excuse me, my lady, but would his lordship and Lady Emily like to have tea with me in the pantry? We have plenty of milk.’

‘I am sure they would love to,’ said Lady Pomfret. ‘Now Ludovic, take Emily’s hand and go with Wheeler. Old Lady Lufton would insist on being a godmother,’ she said apologetically as her children went away with Wheeler, ‘but I suppose we shall get used to it.’

Then Mr Carton came in. And if any reader wishes to know what he was like, he was exactly like what an Oxford don nearer sixty than fifty ought to be; tall and rather untidy, with receding hair, and spectacles which he was always putting on and taking off; of precise speech, capable of vitriolic rancour in the field of scholarship, secretly very kind to his pupils, with no known ties except a mother of eighty who lived at Bognor and did a surprising amount of gardening. With Mr Oriel he had a perpetual friendly difference of opinion about the singing in church, Mr Carton upholding Hymns Ancient and Modern with violence, while Mr Oriel who had High Anglican leanings rather affected a little book called Songs of Praise.

‘You do know Mr Carton, I think, Sally,’ said Mrs Belton to Lady Pomfret. ‘Will you have tea, Mr Carton? You have come just at the right moment, because we can’t quite make out how Mr Oriel and old Lady Pomfret were connected and you are so good at families.’

‘My great-uncle at Greshamsbury —’

‘Edith Pomfret’s mother’s cousin —’

‘That girl there was a queer story about that brought all the money into the Gresham family —’

‘I often heard Lady Pomfret speak of an old Dr Thorne who married an heiress —’

Said Mr Oriel, Mrs Belton, Mr Belton and young Lady Pomfret all at once.

‘Stop,’ said Mr Carton. ‘Wait. I’ll tell you exactly how it is.’

He put his spectacles on, looked piercingly at the party over the top of them as if they were undergraduates, and putting his finger tips together, pronounced judgment.

‘Your great-uncle the bishop, Oriel, married some time in the ’sixties one of Squire Gresham’s daughters whose name for the moment escapes me. His wife’s brother, Frank Gresham, the present man’s great-grandfather, married Mary Thorne who was the illegitimate niece of the Dr Thorne who married Miss Dunstable whose money came from a patent Ointment of Lebanon. Dr Thorne was only a distant cousin of the Ullathorne Thornes, to whom old Lady Pomfret belonged, but the connection is there all right, though I couldn’t give the precise degree.’

He then took off his spectacles, put them into their case, snapped the case shut and put it in his pocket. There was a short silence while his audience digested these facts.

‘My great-uncle had fifteen children,’ said Mr Oriel thoughtfully. ‘His fifteen little Christians he used to call them. Dear, dear.’

There seemed to be no adequate comment on this picture of scenes from clerical life, so it was almost a relief when the bell suddenly rang again and Wheeler came in.

‘It’s Dr Perry, madam,’ she announced, ‘and he said not to disturb you if you were engaged. And did you wish Lady Emily to have a piece of cheese with her tea, my lady? His lordship said she always did at the Towers.’

Lady Pomfret said certainly not and Ludovic was being most untruthful and would Wheeler let her know as soon as the home farm lorry came, because it was high time she took the children home, and then Dr Perry came in, a stout jovial little man who had been the Beltons’ family physician, just as his father before him had been family doctor to the previous generation of Beltons.

‘I was telling my wife, Perry, that your father always said this was the best house in the High Street,’ said Mr Belton. ‘You know everyone, I think.’

Mrs Belton said she would have fresh tea in a minute but Dr Perry refused, saying he was on his way home and had only looked in to give them his wife’s love and bring two pots of her peach jam.

‘I’ve just been up at the Park,’ he added. ‘One of the girls had a nasty boil and I had to lance it. Lots of boils going about now. We’re going to have a nasty winter among the civilian population, Mrs Belton, mark my words. How are your young people?’

Mrs Belton said they had all been ringing up and she hoped to see them, but one never knew till they arrived without any rations late on Saturday.

‘I like the headmistress,’ said Dr Perry. ‘Good-looking in her own style and a lot of character I should say. A nice lot of girls too. They were arriving when I was there and they begin lessons tomorrow. I hope they won’t get measles. There’s any amount about, chicken-pox too. We only want a typhus epidemic. You know Dr Buck has been called up, so I’m single-handed except for Dr Morgan and I can’t abide the woman. She does well enough for half-baked highbrows, but she will talk about psychology to the cottagers and they don’t like it. Quite enough trouble with their children and their rheumatics without all this talk. And if they want a spot of libido they’ll have it all right with all these soldiers and girls about. No need to tell them about that.’

Mr Oriel said it was most distressing and he for one was ready to marry young couples at any moment, if only for the sake of the unborn child.

‘We all know that, Oriel,’ said Dr Perry, who was fond of his pastor though with no very high opinion of his worldly wisdom. ‘But it’s not the unmarrieds; they usually get married all right. It’s the married women with their husbands away. Mrs Humble down near the Three Tuns has just had her second, a fine baby too. I’d like to see Morgan talk psychology to her!’

Upon which Dr Perry laughed rather boisterously, and though all his hearers liked him and knew how good and patient he was on his professional side, it was a distinct relief when Wheeler came in to say the lorry from the Towers was there and Cook was just washing Lady Emily’s hands and face.

‘And I hope, my lady, that the Honourable Giles is keeping well,’ said Wheeler to Lady Pomfret.

‘Splendid, thank you, Wheeler,’ said Lady Pomfret. ‘He cut a tooth yesterday on his sixth birthday; I mean his six months old birthday. Good-bye, Lucy. Let me know if Freddy or Charles want any shooting. Poor Jenks says it isn’t like being a head keeper with no gentlemen out with their guns. His boy in the army who was in hospital is quite fit again and engaged to a nice girl in the Land Army. Come along, children.’

When the ripples of farewell had subsided, Dr Perry said he must be going.

‘Go and see that schoolmistress, Mrs Belton,’ he said. ‘You’ll like her and I think she will be lonely. She’s a cut above the other mistresses. You’d like her, Oriel. A good churchwoman and all that sort of thing. You’ll have to confirm her girls – no, it’s the Bishop that does that of course, though I’d as soon be confirmed by one of the Borgias myself. You’ll have to tell them what it’s all about anyway. You’d like her too, Carton. Talk about Cicero and all that sort of thing. She’s one of that classical lot. Tell your young people to let me know when they want to go to Barchester, Mrs Belton. I’m often at the General Hospital and I can always give them a lift. And I’d like to say,’ said Dr Perry, suddenly showing signs of embarrassment, a state most uncommon with him, ‘that the whole village will miss you at the Park, but it will do us all a lot of good to have you down here, among us. Jove, I’ve kept my surgery waiting twenty minutes.’

Upon this he shook hands with his host and hostess, and bolted out of the house with a red face.

‘A very good man,’ said Mr Oriel slowly, ‘though he pretends he isn’t. But I wish this new headmistress wasn’t a good churchwoman. No, I don’t mean that, but good churchwomen are so apt to want to tell one things and I’d rather not. I suppose this is cowardly though. Are you coming my way, Carton?’

‘“One of that classical lot”!’ Mr Carton exploded with withering scorn. ‘Educated women are no treat to me. Cicero indeed! She probably says Kikero. Thank God the creatures that come to Oxford now are all doing economics; they and their subject are just about fit for each other. Pah!’

Everyone secretly admired a man who could say Pah, one of those locutions more often written than spoken.

‘Well, good-bye,’ said Mr Oriel, looking very hard at the highlight on the nose of Raeburn’s portrait of a former Lord Ellangowan. ‘You know, Perry is a very sensible man. If I’d tried all day I couldn’t have put it better. About the Park I mean. As a matter of fact,’ said Mr Oriel, shifting his gaze to the raven locks of the lovely Lady Ellangowan who was carried off in a decline at twenty-five, ‘we all feel that the Park is Here. Arcot House will be the Park as far as the village is concerned. God bless you both.’

He then felt he had gone too far, looked wildly at the knob on the teapot, shook hands violently with the Beltons and said, ‘Coming, Carton?’

Mr Carton, who had fallen into a kind of trance or dwam during Mr Oriel’s last heartfelt words, suddenly came to and uttered violently the word, ‘Patience.’

‘We do,’ said Mrs Belton earnestly.

‘Tut-tut, I don’t mean that,’ said Mr Carton, whose hearers were again filled with admiration of his vocabulary. ‘And when I say Patience I am wrong. I mean Beatrice. Beatrice Gresham was the girl Oriel’s great-uncle married. I knew it would come to me. Good-bye. I cannot tell you how much I look forward to seeing more of you both, if I may. In fact I have, selfishly, only one regret at your having left the Park – the library.’

‘It’s locked and I’ve got the key,’ said Mr Belton. ‘I’ve got a duplicate. You can have it. No one else wants to go in. I don’t believe any of the children can read at all.’

Mr Carton expressed his. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...