- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Pretty, impecunious Mary Preston, newly arrived as a guest of her Aunt Agnes at the magnificent wooded estate of Rushwater, falls head over heels for handsome playboy David Leslie.

Meanwhile, Agnes and her mother, the eccentric matriarch Lady Emily, have hopes of a different, more suitable match for Mary. At the lavish Rushwater dance party, her future happiness hangs in the balance . . .

Release date: November 22, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

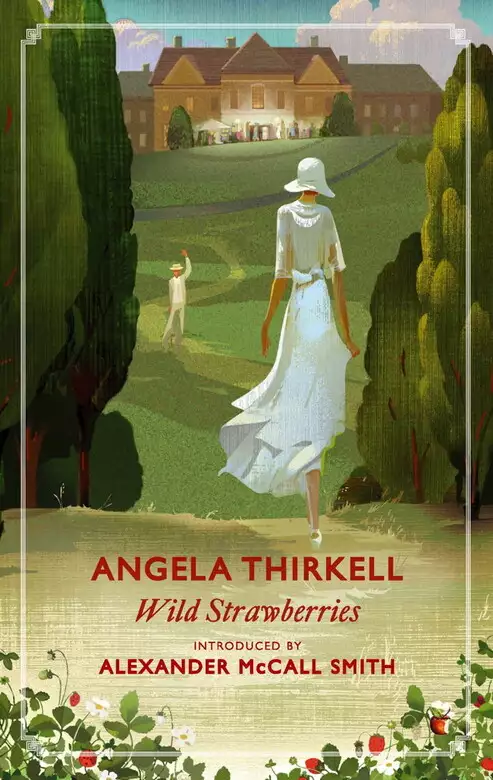

Wild Strawberries

Angela Thirkell

She led her life in much the same milieu as that in which she set her novels. She came from a moderately distinguished family: her father became Professor of Poetry at Oxford, and her mother was the daughter of Edward Burne-Jones, the pre-Raphaelite painter. She was related to both Rudyard Kipling and Stanley Baldwin; she was the goddaughter of J. M. Barrie. Her life, though, was not always easy: there was an unhappy spell living in Australia, and two unsuccessful marriages. Financial exigency meant that she had to make her own way, first as a journalist, and then as the author of a series of novels produced to pay the bills.

Books flowed fast from her pen, and their quality was perhaps uneven. Many of them are now largely forgotten, but amid this enthusiastic somewhat breathless literary output there are some highly enjoyable and amusing novels. High Rising and Wild Strawberries are two such. These books are very funny indeed.

The world she depicts is that of rural England in that halcyon period after the First World War when light began to dispel the stuffiness and earnestness of the Victorian and Edwardian ages. It was a good time for the upper-middle classes: they still lived in largish houses and they still had servants, even if not as many as they used to. They drove cars – made of enamel! Angela Thirkell informs us – and they entertained one another with stylish throwaway comments in which exaggeration played a major role. They were in turn delighted or enraged – all in a rather arch way – by very small things.

The social life depicted in these books is fascinating. We are by no means in Wodehouse territory – Thirkell’s characters do have jobs, and they do not spend their time in an endless whirl of silliness. Occasionally, though, they express views or use language that surprises or even offends the modern ear – there is an instance of this in the wording of one of the songs in Wild Strawberries. But this, of course, merely reflects the attitudes of the time: it is a society in which nobody is in any doubt about his or her place. Servants observe and may comment, for example, but they must not get above themselves. Miss Grey, who takes up the position of secretary to Mr Knox in High Rising, is not exactly a servant, but she is an employee and should remember not to throw her weight around with her employer’s friends. Of course she does not remember this, which is a major provocation to the novel’s heroine, Laura Morland. One cannot help but feel sympathy for Miss Grey, who is described as having no relations to whom she can be expected to go. That was a real difficulty for women: unless you found a husband or were able to take one of the relatively few jobs that were available to you (and somebody like Miss Grey could not go into service), you were dependent on relatives. Finding a husband was therefore a deadly earnest task – almost as important as it was in the time of Jane Austen.

The children in this world were innocent and exuberant. In High Rising we see a lot of Laura’s son, Tony, whom she brings home from his boarding school at the beginning of the book. Like most of those whom we encounter in Thirkell’s novels, Tony is overstated to the point of being something of a caricature. He is as bouncy and excitable as a puppy dog, full of enthusiasm for trains, a subject by which he is obsessed. He knows all the technical details of trains – their maximum speed, and so on – and spends the ‘tips’ he receives from adults on the purchase of model carriages and engines. These tips are interesting. It was customary for adult visitors to give presents to the children of the house, and a boy might reasonably expect such a gift simply because he was there at the time of the visit. As a child I remember getting these tips – not earning them in any way, just getting them as of right. Today, children would be surprised if anybody gave them money and would probably immediately reject it, it having been drilled into them that such gifts are always to be refused.

Tony also has a degree of freedom unimaginable today. Not only is he interested in model trains; his passion for railways extends to the real thing, and he is allowed to go off to the local railway station by himself. There the stationmaster permits him to sit in the signal box and also to travel in the cab on shunting engines. Whatever else is unlikely in the novels, this sounds entirely realistic. Childhood was different then.

Engaging though these period details may be, this is in itself insufficient reason to read Thirkell. What makes her novels so delightful is their humour. The affairs that occupy the minds of her characters are classic village concerns. In that respect, we could as easily be in Benson’s Tilling as we are in the Risings. There are dislikes and feuds; there are romantic ambitions; there are social encounters in which people engage in highly amusing exchanges. These come thick and fast, just as they do in Tilling, and are every bit as delicious. Affection for the social comedy is not something we should have to apologise for, even if that sort of thing is eschewed in the contemporary novel. Such matters may seem unimportant, but they say a lot about human nature. Above all, though, we do not read Angela Thirkell for profundity of emotional experience; we read her for the pleasure of escape – and there is a perfectly defensible niche for escapist fiction in a balanced literary diet.

Another attraction is the coruscating wit of the dialogue and, to an extent, of the authorial observations. Angela Thirkell is perhaps the most Pym-like of any twentieth-century author, after Barbara Pym herself, of course. The essence of this quality is wry observation of the posturing of others, coupled with something that comes close to self-mockery. The various members of the Leslie family in Wild Strawberries are extremely funny. Lady Leslie, like Mrs Morland in High Rising, is a galleon in full sail, and we can only marvel at and delight in the wit of both.

The exchanges that take place between the characters in these books would look distinctly out of place in a modern novel – but therein, I believe, lies their charm. These people talk, and behave, as if they are in a Noël Coward play. In real life, a succession of insouciant sparkling observations would become tedious, but it is impossible to read these books without stopping every page or two to smile or to laugh at the sheer audacity of the characters and their ebullient enthusiasms. We are caught up by precisely those questions that illuminate the novels of Jane Austen: who will marry whom? Who will neatly be put in her place? Which men will escape and which will be caught? These are not the great questions of literature, but they are diverting, which is one of the roles of fiction. Angela Thirkell creates and peoples a world whose note can be heard today only in the tiniest of echoes, but in her books it comes through loud and clear, reminding us that the good comic novel can easily, and with grace, transcend the years that stand between us and the time of its creation.

Alexander McCall Smith

2012

The Vicar of St Mary’s, Rushwater, looked anxiously through the vestry window which commanded a view of the little gate in the churchyard wall. Through this gate the Leslie family had come to church with varying degrees of unpunctuality ever since the vicar had been at Rushwater, nor did it seem probable that they had been more punctual before his presentation to the living. It was a tribute to the personality of Lady Emily Leslie, the vicar reflected, that everyone who lived with her became a sharer in her unpunctuality, even to the weekend guests. When first the vicar came to St Mary’s, the four Leslie children were still in the nursery. Every Sunday had been a nervous exasperation for him as the whole family poured in, halfway through the General Confession, Lady Emily dropping prayer books and scarves and planning in loud, loving whispers where everyone was to sit. During the War the eldest boy had been in France, John, the second boy, at sea, and Rushwater House was a convalescent home. But Lady Emily’s vitality was unabated and her attendance at morning service more annoying than ever to the harassed vicar, as she shepherded her convalescent patients into her pew, giving unnecessary help with crutches, changing the position of hassocks, putting shawls round grateful embarrassed men to protect them from imaginary draughts, talking in a penetrating whisper which distracted the vicar from his service, behaving altogether as if church was a friend’s house. There came a moment at which he felt it to be his duty for the sake of other worshippers to beg her to be a little more punctual and a little less managing. But before he had summoned up enough courage to speak, the news came that the eldest son had been killed. When the vicar saw, on the following Sunday, Lady Emily’s handsome face, white and ravaged, he vowed as he prayed that he would never let himself criticise her again. And although on that very Sunday she had so bestirred herself with cushions and hassocks for the comfort of her wounded soldiers that they heartily wished they were back in hospital, and though she had invented a system of silent communication with Holden, the sexton, about shutting a window, thus absorbing the attention of the entire congregation, the vicar had not then, nor ever since, faltered from his vow.

At her daughter Agnes’s wedding to Colonel Graham she had for once been on time, but her attempts to rearrange the order of the bridesmaids during the actual ceremony and her insistence on leaving her pew to provide the bridegroom’s mother with an unwanted hymn book had been a spectacular part of the wedding. As for the confirmation of David, the youngest, the vicar still woke trembling in the small hours at the thought of the reception which Lady Emily had seen fit to hold in the chancel afterwards, though apparently without in the least offending the bishop.

Rushwater adored her. The vicar knew perfectly well that Holden deliberately prolonged his final bellringing to give Lady Emily every chance, but had never had the courage to charge him with it. Just then the gate clicked and the Leslie family entered the churchyard. The vicar, much relieved, turned from the window and made ready to go into the church.

It was a large family party that had come over from Rushwater House. Lady Emily, slightly crippled of late with arthritis, walked with a black crutch stick, holding her second son, John’s, arm. Her husband walked on her other side. Agnes Graham followed with two nannies and three children. Then came David with Martin, the Leslies’ eldest grandson, a schoolboy of about sixteen. It was his father who had been killed in the War.

Lady Emily halted her cavalcade in the porch.

‘Now, Nannie,’ she said, ‘wait a minute and we will see where everyone is to go. Now, who is having communion?’

Both the nurses looked away with refined expressions.

‘Not you, Nannie, and not Ivy, I suppose,’ said Lady Emily.

‘Ivy can go to early communion any morning she wishes, my lady,’ said Nannie, icily broadminded. ‘I’m chapel myself.’

Lady Emily’s face became distraught.

‘Agnes,’ she cried, laying a gloved hand on her daughter’s arm, ‘what have I done? I didn’t know Nannie was chapel. Could we arrange for one of the men to run her down to the village if it isn’t too late? I’m afraid it’s Weston’s day off, but I dare say one of the other men could drive the Ford. Or won’t it matter?’

Agnes Graham turned her lovely placid eyes on her mother.

‘It’s quite all right, Mamma,’ she said in her soft, comfortable voice. ‘Nannie likes coming to church with the children, don’t you, Nannie? She doesn’t count it as religion.’

‘I was always brought up to the saying “Thy will not Mine”, my lady,’ said Nannie, suddenly importing a controversial tone into the conversation, ‘and know where my duty lies. Baby, don’t pull those gloves off, or Granny won’t take you to the nice service.’

‘For Heaven’s sake, Emily,’ interrupted Mr Leslie advancing, tall, fresh-faced, heavily built, used to getting his own way except where his wife was concerned. ‘For Heaven’s sake don’t dawdle there talking. Poor old Banister is dancing in the pulpit and Holden has stopped ringing his passing bell. Come along.’

No one knew whether Mr Leslie was as ignorant of ecclesiastical matters as he pretended to be, but he had taken up from his earliest years the attitude that one word was as good as another.

‘But, Henry, the question of communion is truly important,’ said Lady Emily earnestly. ‘The ones that wish to escape must sit on the outside edge of the pew and the ones that are staying must sit inside, to make less fuss. Only I must sit on the outside, because my knee gets so stiff if I sit inside, but if I go in the second pew with Nannie and Ivy and the children, they can all get past me quite well, can’t they, Nannie?’

‘Yes, my lady.’

‘Very well, then; you go in the front pew, Henry, with Agnes and David and Martin, and the rest of us will go behind. Only mind you put Agnes right inside against the wall, because she is staying for communion, and if she is outside you will have to walk over her and the boys too.’

‘But Martin and I aren’t staying for communion,’ said David.

‘No, darling? Well, just as you like. It is disappointing, in a way, because the vicar does dearly love a good house – but what I meant was that if Agnes were outside, you and your father and Martin would all have to walk over her, not that he would have to walk over her and you.’

By this time Nannie, a young woman of strong character who was kind enough to tolerate her employers for the sake of the babies they provided, had taken her charges into the second pew and distributed Ivy and herself among them so that no two children should sit together. The rest of the party followed between the rows of the already kneeling congregation. Just as they came to the nursery pew, Lady Emily uttered a loud exclamation.

‘John! I had forgotten about John. John, if you don’t want any communion you had better go in front with David and Martin and the others, only let your father have the corner seat.’

John helped his mother to settle into her pew, and then slipped into the pew behind. Lady Emily dropped her stick with a clatter into the aisle. John got up and handed it to his mother, who flashed a brilliant smile at him and said in an audible aside:

‘I can’t kneel, you know, because of my stiff leg, but my spirit is on its knees.’

But before her spirit could settle to its devotions she leaned forward and tapped her husband’s shoulder.

‘Henry, are you reading the lessons?’ she inquired.

‘What’s that?’ asked Mr Leslie, through the Venite.

Lady Emily poked at Agnes with her stick.

‘Darling,’ she whispered loudly, ‘is your father reading the lessons?’

‘Of course I am,’ said Mr Leslie. ‘Always read the lessons.’

‘Then, what are they?’ asked Lady Emily. ‘I want to find them in the Bible for the children.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Mr Leslie, crossly. ‘Not my business.’

‘But, Henry, you must know.’

Mr Leslie turned his body round and glared at his wife.

‘I don’t know,’ he insisted, red in the face with his efforts to whisper gently, but angrily and audibly. ‘Holden marks the places for me. Look in your prayer book, Emily, you’ll find it all in the beginning number of the Beast or something.’

With which piece of misinformation he turned round again and went on with his singing. As he announced the first lesson from the lectern, his wife repeated the book, chapter and verse aloud after him, adding, ‘Remember that, everyone.’ She then began to hunt through the Bible. Agnes’s eldest child, James, who was just seven, looked at her efforts with some impatience.

‘Just open it anywhere, Granny,’ he whispered.

But his grandmother insisted not only on finding the place, but on pointing it out to all the occupants of both pews. By the time the second lesson was reached she had mislaid her spectacles, so James undertook to find the place for her. While he was doing this she leaned over to Nannie and said:

‘Do you have the lessons in chapel?’

But Nannie, knowing her place, pretended not to hear.

When the vicar began his good and uninteresting sermon, James snuggled up to his grandmother. She put an arm round him and they sat comfortably together, thinking their very different thoughts. Never did Emily Leslie sit in her pew without thinking of the beloved dead: her firstborn buried in France, and John’s wife Gay, who after one year of happiness had left him wifeless and childless. John had left the navy after the War, gone into business, and was doing well, but his mother often wondered if anyone or anything would ever have power to stir his heart again. Whenever he was off his guard his mother’s heart was torn by the hard, set lines of his face. Otherwise he seemed happy enough, prospered, was thinking of Parliament, helped his father with the estate, was a kind uncle to Martin and to Agnes’s children, went to dances, plays and concerts in London, rode and shot in the country. But Lady Emily sometimes felt that if she came up behind him quietly and suddenly she might see that he was nothing but a hollow mask.

Then there was Martin, so ridiculously like his dead father, and as happy as anyone of sixteen who knows he is really grown-up can expect to be. His mother had remarried, and though Martin was on excellent terms with his American stepfather, he made Rushwater his home, much to the secret joy of his grandparents. Inheritance and death duties were not words which troubled Martin much. He knew Rushwater would be his some day, but had the happy confidence of the young that their elders will live for ever. His most pressing thoughts at the moment were about the possible purchase of a motor bicycle on his seventeenth birthday, and his hopes that his mother would forget her plan of sending him to France for part of the summer holidays. It would be intolerable to have to go to that ghastly abroad when one might be at Rushwater and play for the village against neighbouring elevens. Also he wanted to be in England if David pulled off that job with the BBC.

David should by rights have been Uncle David, but though Martin dutifully gave his title to his Uncle John, he and David were on equal terms. David was only ten years older than he was, and not the sort of chap you could look on as an uncle. David was like an elder brother, only he didn’t sit on you as much as some chaps’ elder brothers did. David was the most perfect person one could imagine, and when one was older one would, with luck, be exactly like David. Like David one would dance divinely, play and sing all the latest jazz hits, be president of one’s university dramatic society, write a play which was once acted on a Sunday, produce a novel which only really understanding people read, and perhaps, though here Martin’s mind rather shied off the subject, have heaps of girl. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...