- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

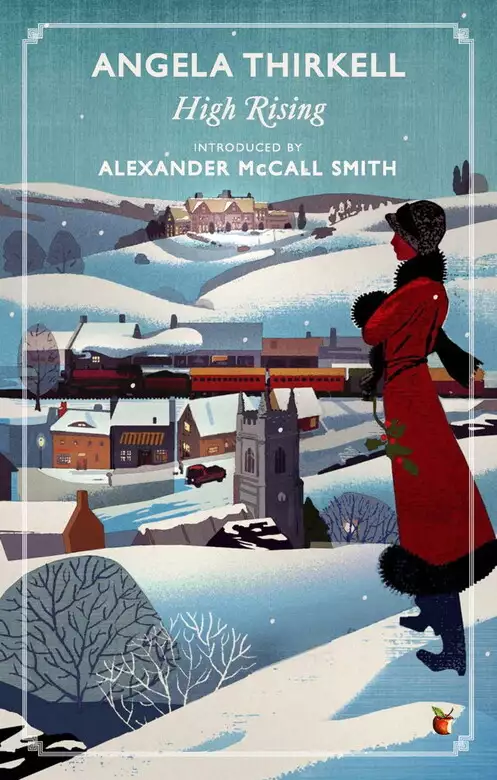

Successful lady novelist Laura Morland and her boisterous young son, Tony, set off to spend Christmas at her country home in the sleepy surrounds of High Rising. But Laura's wealthy friend and neighbour, George Knox, has taken on a scheming secretary whose designs on marriage to her employer threaten the delicate social fabric of the village.

Can clever, practical Laura rescue George from Miss Grey's clutches and, what's more, help his daughter, Miss Sibyl Knox, to secure her longed-for engagement?

Utterly charming and very funny, High Rising is irresistible comic entertainment.

Release date: November 22, 2012

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

High Rising

Angela Thirkell

She led her life in much the same milieu as that in which she set her novels. She came from a moderately distinguished family: her father became Professor of Poetry at Oxford, and her mother was the daughter of Edward Burne-Jones, the pre-Raphaelite painter. She was related to both Rudyard Kipling and Stanley Baldwin; she was the goddaughter of J. M. Barrie. Her life, though, was not always easy: there was an unhappy spell living in Australia, and two unsuccessful marriages. Financial exigency meant that she had to make her own way, first as a journalist, and then as the author of a series of novels produced to pay the bills.

Books flowed fast from her pen, and their quality was perhaps uneven. Many of them are now largely forgotten, but amid this enthusiastic somewhat breathless literary output there are some highly enjoyable and amusing novels. High Rising and Wild Strawberries are two such. These books are very funny indeed.

The world she depicts is that of rural England in that halcyon period after the First World War when light began to dispel the stuffiness and earnestness of the Victorian and Edwardian ages. It was a good time for the upper-middle classes: they still lived in largish houses and they still had servants, even if not as many as they used to. They drove cars – made of enamel! Angela Thirkell informs us – and they entertained one another with stylish throwaway comments in which exaggeration played a major role. They were in turn delighted or enraged – all in a rather arch way – by very small things.

The social life depicted in these books is fascinating. We are by no means in Wodehouse territory – Thirkell’s characters do have jobs, and they do not spend their time in an endless whirl of silliness. Occasionally, though, they express views or use language that surprises or even offends the modern ear – there is an instance of this in the wording of one of the songs in Wild Strawberries. But this, of course, merely reflects the attitudes of the time: it is a society in which nobody is in any doubt about his or her place. Servants observe and may comment, for example, but they must not get above themselves. Miss Grey, who takes up the position of secretary to Mr Knox in High Rising, is not exactly a servant, but she is an employee and should remember not to throw her weight around with her employer’s friends. Of course she does not remember this, which is a major provocation to the novel’s heroine, Laura Morland. One cannot help but feel sympathy for Miss Grey, who is described as having no relations to whom she can be expected to go. That was a real difficulty for women: unless you found a husband or were able to take one of the relatively few jobs that were available to you (and somebody like Miss Grey could not go into service), you were dependent on relatives. Finding a husband was therefore a deadly earnest task – almost as important as it was in the time of Jane Austen.

The children in this world were innocent and exuberant. In High Rising we see a lot of Laura’s son, Tony, whom she brings home from his boarding school at the beginning of the book. Like most of those whom we encounter in Thirkell’s novels, Tony is overstated to the point of being something of a caricature. He is as bouncy and excitable as a puppy dog, full of enthusiasm for trains, a subject by which he is obsessed. He knows all the technical details of trains – their maximum speed, and so on – and spends the ‘tips’ he receives from adults on the purchase of model carriages and engines. These tips are interesting. It was customary for adult visitors to give presents to the children of the house, and a boy might reasonably expect such a gift simply because he was there at the time of the visit. As a child I remember getting these tips – not earning them in any way, just getting them as of right. Today, children would be surprised if anybody gave them money and would probably immediately reject it, it having been drilled into them that such gifts are always to be refused.

Tony also has a degree of freedom unimaginable today. Not only is he interested in model trains; his passion for railways extends to the real thing, and he is allowed to go off to the local railway station by himself. There the stationmaster permits him to sit in the signal box and also to travel in the cab on shunting engines. Whatever else is unlikely in the novels, this sounds entirely realistic. Childhood was different then.

Engaging though these period details may be, this is in itself insufficient reason to read Thirkell. What makes her novels so delightful is their humour. The affairs that occupy the minds of her characters are classic village concerns. In that respect, we could as easily be in Benson’s Tilling as we are in the Risings. There are dislikes and feuds; there are romantic ambitions; there are social encounters in which people engage in highly amusing exchanges. These come thick and fast, just as they do in Tilling, and are every bit as delicious. Affection for the social comedy is not something we should have to apologise for, even if that sort of thing is eschewed in the contemporary novel. Such matters may seem unimportant, but they say a lot about human nature. Above all, though, we do not read Angela Thirkell for profundity of emotional experience; we read her for the pleasure of escape – and there is a perfectly defensible niche for escapist fiction in a balanced literary diet.

Another attraction is the coruscating wit of the dialogue and, to an extent, of the authorial observations. Angela Thirkell is perhaps the most Pym-like of any twentieth-century author, after Barbara Pym herself, of course. The essence of this quality is wry observation of the posturing of others, coupled with something that comes close to self-mockery. The various members of the Leslie family in Wild Strawberries are extremely funny. Lady Leslie, like Mrs Morland in High Rising, is a galleon in full sail, and we can only marvel at and delight in the wit of both.

The exchanges that take place between the characters in these books would look distinctly out of place in a modern novel – but therein, I believe, lies their charm. These people talk, and behave, as if they are in a Noël Coward play. In real life, a succession of insouciant sparkling observations would become tedious, but it is impossible to read these books without stopping every page or two to smile or to laugh at the sheer audacity of the characters and their ebullient enthusiasms. We are caught up by precisely those questions that illuminate the novels of Jane Austen: who will marry whom? Who will neatly be put in her place? Which men will escape and which will be caught? These are not the great questions of literature, but they are diverting, which is one of the roles of fiction. Angela Thirkell creates and peoples a world whose note can be heard today only in the tiniest of echoes, but in her books it comes through loud and clear, reminding us that the good comic novel can easily, and with grace, transcend the years that stand between us and the time of its creation.

Alexander McCall Smith

2012

The headmaster’s wife twisted herself round in her chair to talk to Mrs Morland, who was sitting in the row just behind her.

‘I can’t make out,’ she said reflectively, ‘why all the big boys seem to be at the bottom of preparatory schools and the small ones at the top. All those lower boys who got prizes were quite large, average children, but when we get to the upper forms they all look about seven, and undersized at that. Look at the head of the Remove for instance – he is just coming up the platform steps now.’

Mrs Morland looked. In front of her was the platform, where the headmaster stood behind a rapidly diminishing pile of prizes. On each side were the assistant masters, wearing such gowns as they could muster. A shrimp-like little boy in spectacles was coming up to get his prizes.

‘That’s him – Wesendonck,’ said the headmaster’s wife. ‘And what a name to send a boy to school with. Such a nice child, too. I hope he will be able to carry all his prizes. I am always telling Bill to have them done up safely. Poor Bill is nearly speechless with a bad cold and all the talking today. I hope he’ll get through.’

At this moment the headmaster found Master Wesendonck’s tall pile of books slipping from his grasp. He juggled frantically with them for a moment and then, to the infinite joy of some two hundred boarders and day boys, they crashed to the ground in all directions. A bevy of form masters rushed forward to the rescue. Master Wesendonck, realising with immense presence of mind that his natural enemies were for once in their proper place, grovelling on the floor, stood still and did nothing, ignoring the shrieks of joy and abuse which his young friends poured upon him from the galleries of the school hall. Seldom had the time and the place and the very unfortunate name come together at such a propitious moment. Few of the jokes were funny, and none of them original, but they gave great satisfaction, and pandemonium reigned.

‘Isn’t Bill going to bark at them?’ asked Mrs Morland anxiously; for the headmaster stood blandly surveying the tumult, making no effort to quell it.

‘In about a minute,’ said the headmaster’s wife. ‘I can see him sucking a throat lozenge. When he has swallowed it, he’ll give tongue. And I can’t think,’ she added, surveying with some disfavour the scrum of masters on the floor, ‘why on earth headmasters’ wives in novels fall in love with assistant masters, or assistant masters with them for that matter. Just look at ours.’

‘“Just-look-at-the-maze-in-the-house: jever-see-such-maze?”’ murmured Mrs Morland. Certainly, from M. Dubois, the French master, who had been so long at the school that the boys despised him now more from tradition than conviction, to Mr Ferris, the latest addition to the staff, whom the headmaster’s wife was perpetually mistaking for an upper boy who had grown a good deal in the holidays, there was no face among that collection of excellent, highly educated (or athletic), hard-working, conscientious men which could, one would think, cause a flutter in any female breast.

‘And yet they are mostly married,’ continued the headmaster’s wife, ‘and the ones that aren’t married are engaged. I suppose it’s a law of Nature, only I wish Nature would exercise natural selection, which is one of the things she is famous for, because the masters, left to themselves, don’t. What I have to bear from having masters’ wives to tea—’

But at this moment the headmaster swallowed the lozenge, and in the voice of a sergeant-major who had been educated among sea-lions, simply remarked, ‘Be quiet!’

There was instantaneous silence.

‘Bill barked beautifully, didn’t he?’ said his proud wife to Mrs Morland. ‘Listen, Laura, wait till the other horrible parents have gone, and have some tea with me. Bring Tony, too, if you like.’

‘All right, Amy, but I can’t stay long. I’m driving down to the cottage.’

The rest of the prizes were distributed without mishap, and boys and parents began to surge out of the hall. Laura waited by the entrance to claim her own child, whom she could barely recognise in his revolting Eton collar. When Tony was first sent to school, Laura had rung up the headmaster’s wife, an old friend, to ask if the regulation Eton suit, which nothing, she said, would ever induce her to let Tony appear in at home, was really necessary for Sundays. Amy had asked what kind of shape Tony was, and hearing that he was a strongly built, thick-set little boy, said, ‘Of course not. He’d look ghastly in Etons. Get him a blue serge suit for best.’ So the Eton collar was the only concession to school respectability. Which all goes to show what a very sterling woman Amy Birkett was. But as little boys all look exactly alike, with hair twirling round and round from a starting point on the backs of their heads, round bulging cheeks, and napes that still have some of the charm of the nursery about them, it was not easy to spot Tony, especially as the whole school was reduced to a common denominator by the unnatural cleanliness enforced upon it for the prizegiving ceremony. At last something tugging at her arm made itself visible as Tony.

‘Mother, did you hear the noise the chaps made when Donkey’s books went down? Did you hear me, Mother? I was yelling

“Donk’s an ass,

Bottom of the class.”

Mother, did you hear it?’

Laura wondered, as she had often wondered with the three older boys, why one’s offspring are under some kind of compulsion to alienate one’s affections at first sight by their conceit, egoism, and appalling self-satisfaction. But, recognising the inevitable, she said yes, she had heard, and told him to get his things ready and then come to Mr Birkett’s study for tea.

‘Oh, Mother, must I?’

‘Why not?’

‘Go to tea with Mrs Birky? Oh, Mother, I couldn’t. She’d think my hair wasn’t properly brushed or something. She goes off pop if you aren’t tidy.’

Laura, wondering, as before, why one’s gently bred and nurtured children have such a degradingly common streak in them, merely repeated her order to Tony. His soft face assumed a sulky expression, which, however, cleared up immediately as he caught sight of Master Wesendonck, surrounded by his admiring mother and sisters. He walked past the group, repeating in a loud, abstracted voice his famous distich,

‘Donk’s an ass,

Bottom of the class,’

and was rewarded by a friendly attack from the victim of the libel. The two little boys disappeared in a scuffle of arms and legs into the boarders’ quarters. Laura, feeling rather guilty towards the Wesendonck family, slipped into the large classroom where the common herd of parents were being fed. The school sergeant, a huge, powerful, gentle creature, was stationed at the door to prevent boys getting in and eating the parents’ tea.

‘Good afternoon, sergeant,’ said Laura. ‘How is Tony getting on?’

‘Nicely, Mrs Morland. I wouldn’t say but what he mightn’t be as good as young Dick was. Talks too much, though. Funny, if you come to think of it, his elder brothers weren’t at all talkative young gentlemen, but young Tony, well, he wasn’t behind the door when tongues were given out. Still, he’s shaping well. I hope we shall see you at our Boxing Competition next term, Mrs Morland.’

Without waiting for her answer, he made a plunge into the tea-room, and brought out two small boys by the scruff of the neck.

‘Mother or no mother,’ he said severely, ‘orders are given, and none of you boys goes into the tea-room. Get along with you.’

Letting Laura through, he stood like Apollyon, blocking the doorway to the boys outside.

Laura wandered through the tea-room, but could not see Amy anywhere. Presently her great friend, Edward, came up to her. Edward, who had enlisted at sixteen ‘for company’, had found his ideal job after the war as factotum and friend of all mankind at the school, with the company which he so much loved perpetually renewed. He could clean boots like an officer’s servant and patch them like a real cobbler; clean knives and sharpen them; mend the boys’ bats, skates, racquets, cameras; cut hair; sing any popular song ever written; repair the headmaster’s wireless and drive his car. When the whole kitchen staff went down with influenza, was it not Edward who held the breach for two days, cooking boiled beef and dumplings in the copper? When the sanatorium overflowed during the same epidemic, was it not Edward who took his turn as night nurse in the temporary hospital, and sang the convalescents to sleep with highly unsuitable songs from Flanders? On that blissful occasion when the local power station failed and all the school lights went out, and the Birketts were away, and Johnson and Butters collided in a dark passage where they had no business to be, and Johnson had a bleeding lip and Butters an eyebrow laid open, was it not Edward who had the wits to run them both over in one of the masters’ cars to the doctor’s house and get them sewn up at once, returning so swiftly that no one had time to think of any serious mischief to do? There was even a tradition that, in a crisis, Edward had taken the place of nursery-maid in Mrs Birkett’s nursery and wheeled her two little girls in a perambulator. But this was looked upon as going a little too far, and was slurred over by the school. One didn’t like to associate Edward in any way with those two great gawky girls, Rose and Geraldine. At least that was what the young chivalry of England felt.

‘If you were looking for Mrs Birkett, madam,’ said the omniscient Edward, ‘she is gone over to the house and hopes you’ll follow. She said she couldn’t stand no more parents at any price, madam, if you understand me.’

Laura thanked him, and wound her way through the crowd of parents and across to the headmaster’s house, where she found Amy in the study.

‘Bill was so exhausted and voiceless that I’ve sent him to lie down for a bit,’ said Amy. ‘I expect he had a touch of flu. Come and sit down and tell me about the family. Is Gerald enjoying China?’

‘It’s Dick who is in China, at least somewhere about on the China station, whatever that is. He quite likes it, and he loves the ship.’

‘Oh, it’s Gerald who’s in Burma, then. How’s he getting on?’

‘No, that’s John. He’s getting on nicely. He hopes to get back next Christmas. Gerald is the one who explores. He has got a good paying job with some Americans in Mexico. He says it’s great fun. It sounds horrid.’

‘I’m sorry, Laura dear, that I mix your family up so. It’s so confusing of you to have four boys. And whenever I got used to a Morland Minor, his elder brother would leave us and his younger brother come on, and then he was Major and there was a new Minor. Most confusing. But I’m glad they’re all well. Things are easier now, aren’t they?’

‘If you mean money, yes. Gerald and John are self-supporting, bless them, and Dick almost. So really they cost me nothing except presents, and holidays when they come back. There’s only Tony now.’

‘But he’ll get scholarships, like Gerald.’

‘Tony has a splendid natural resistance to learning in any form,’ said Laura, in a resigned voice. ‘I expect he’ll be a pig-farmer.’

‘Then you can live on bacon, and not work so hard. Are you always writing?’

‘Mostly. But it’s much easier now than when I had three at school and Tony at home. I am actually saving up for my old age.’

‘Come in,’ called Amy, to a knock at the door. Tony came in. He had evidently got at somebody’s brilliantine. His hair was irregularly parted down the middle and slabbed shiningly down on each side, and he brought with him a powerful odour of synthetic honey and flowers.

‘Foul child!’ cried Amy, ‘what have you been doing? Have some tea.’

Tony appeared to be accustomed to his headmaster’s wife, for he evinced no discomposure, and seating himself, replied, ‘It’s only a little Johnson’s hair fixative, Mrs Birkett. Two of the chaps poured it on for me, and I brushed it down. Did you hear the noise, Mrs Birkett, when Wesendonck’s books fell down? I was shouting like anything.’

‘Hear it?’ said Amy. ‘Why, you broke both Mr Birkett’s ear-drums and he has gone to bed.’

Tony looked alarmed.

‘If this weren’t a tea-party and the end of the term and Christmas next week,’ said Laura, ‘I would kill you, Tony. Look at your suit.’

Indeed, signs of the whole-hearted way in which the two unspecified chaps had entered into the spirit of the fixative job were visible on Tony’s collar and all down his jacket and waistcoat.

‘Oh, that’s all right,’ said Tony, ‘we wiped the rest off the floor with Swift-Hetherington’s gym shorts and then matron came in and went off pop.’

‘Well, thank heaven you’re going,’ said the headmaster’s wife.

‘You’ll come to me for a few days in the holidays, won’t you, Amy?’ said Laura, as they kissed goodbye.

‘Love to. Bill is taking the girls to Switzerland for a fortnight. I’ll let you know the dates and invite myself for a night or two.’

‘My love to Bill. I. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...