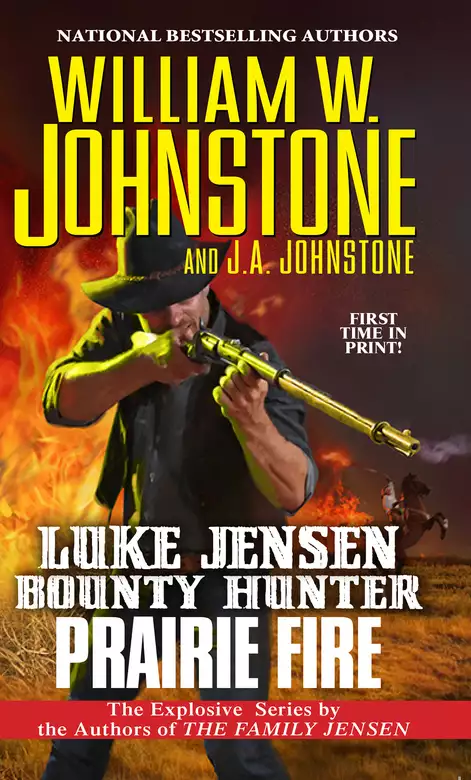

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Johnstone Country. Ready, Aim, Kill.

Luke Jensen tracks down a deranged Yankee-turned-outlaw with a burning passion to torch the prairies, torment the townsfolks, and turn all he sees into a smoldering cinder . . .

CAUTION: CONTENTS MAY BE FLAMMABLE

In the darkest days of the Civil War, Neville Goldsmith set the world on fire. As Captain for the Union Army, he marched with General Sherman through Georgia, setting homes and cities ablaze with sadistic glee. For Goldsmith, starting fires was a lifelong obsession. And when the war ended, he set his sights on the great American West—to burn it all to the ground . . .

Years later, Luke Jensen learns about a series of fires wreaking havoc from the Dakota Territory to Kansas. Each fire appears to be man-made—a way to distract the locals while outlaws rob their banks and loot their towns. The gang’s leader is the demented firebug Goldsmith, along with an equally psychotic partner, Trask. As their fiery reign of terror rages out of control, Luke Jensen decides to do something crazy himself: Infiltrate the gang—and fight fire with gunfire.

Live Free. Read Hard.

Release date: January 25, 2022

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 304

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Prairie Fire

William W. Johnstone

The Union burned Atlanta.

In the beginning, General William Tecumseh Sherman’s army was intent on destroying only those buildings capable of supporting Confederate military operations. However, it wasn’t long before roving bands of undisciplined soldiers, half-crazed from the death and destruction they had wrought already during their march across Georgia, spread the arson to civilian homes, and soon the city was an inferno.

Even as the funeral pyre that was Atlanta continued smoldering and thick columns of black smoke climbed into the sky, the Military Division of Mississippi, spearheaded by the Army of Georgia on General Sherman’s right-wing, marched on toward the sea. The orders to show restraint in foraging for supplies and destroying only vital structures and military materials fragmented as quickly as they had in Atlanta.

Sherman’s troops had burned Atlanta. Now they set the whole state of Georgia on fire. What became known as “Sherman’s March to the Sea” was the most brutal military strategy since the Romans burned and salted Carthage.

Which suited some of the Union officers just fine.

Colonel Neville Goldsmith loved fire. A company commander in the XIV Corps of the Army of Georgia, he hadn’t yet seen nearly enough burning. Atlanta had been just about right, but there weren’t enough Atlantas. Never could be enough, as far as Colonel Goldsmith was concerned.

Fire cleansed. It was a magical, living animal that breathed and ate to live. Fire purified as it destroyed, and to Colonel Goldsmith nothing needed purifying more than the hated Confederacy. Let the whole South burn away. Let it disappear in rising smoke, the ashes scattered by the wind.

This was exactly what Goldsmith intended to do.

He shifted on his mount, a strong, bay-colored Morgan horse, and watched his infantry marching past him along the road down the low hill from where he surveyed them. General Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 120 had been clear. The advance army was to forage liberally for supplies. To that end, each command was to create scout units dedicated to the task of perpetual resupply.

Currently, Goldsmith waited for word from his own foragers. Beside him was a young lieutenant in charge of the reconnaissance platoon riding vanguard to the main troop column. Barely in his twenties, the lieutenant couldn’t have grown a beard to save his life.

He finished his scouting report and sat patiently waiting for some comment from Goldsmith. The colonel felt the junior officer’s eyes on him. Tall and whipcord lean, Goldsmith presented a startling figure to those unaccustomed to the sight of him.

As a child, he’d tried burning down his home while his family slept inside. He had set fires before, many of them, but never anything as big as a house. And never anything with something living inside it to serve as sacrifices to the hungry flames. Just the thought of that made his heart slug madly in his chest in anticipation.

But the lure of the blaze and the exquisite screaming from inside the house proved too mesmerizing, and he’d been caught off-guard by the rapid spread of the flames and been badly burned when he was too close to a collapsing wall. As a result, the left side of his body was a gnarled and twisted, pink mass of knotted scar tissue. It ran from his waist, up his arm from the back of his hand, across his neck to his face.

The facial scars twisted the corner of his mouth into a permanent sneer. He hadn’t lost his eye, but the fire had damaged it so that the perpetually reddened orb constantly wept. His scalp was seared so that wispy hairs grew only sporadically on that side of his head.

When turned so that only his right profile was visible, he was still a handsome, if rather severe-looking, man.

But when he was angry, facing someone straight on, his face became truly terrifying.

Slowly, Goldsmith pulled a lucifer from his breast pocket and placed it carefully in the corner of his mouth. He turned his head. Realizing he’d been caught staring like a boy seeing his first naked girl, the lieutenant flushed in embarrassment and looked away. His mount, sensing his nervousness, snorted and stepped sideways, ready to bolt. The young officer was barely able to calm the horse.

“That will be all, Lieutenant,” Goldsmith said.

The colonel’s voice was hoarse and gravelly. The fire had damaged his vocal cords, too. When he spoke, it reminded men of the grinders in rock quarries, smashing stones to pebbles in a great grinding of gears. Goldsmith’s words came out sounding rough-edged and uneven.

“Yes, sir!”

The lieutenant half-shouted the response in his haste to make his exit. He gave his horse its head and rode away at a gallop. His fear made Goldsmith grin. Goldsmith enjoyed the effect he had on others. He loved the terror he saw in the eyes of Southern civilians when his men rode onto their property.

I’m going to miss this war when it’s over, he thought.

Just as the line of infantry gave way to the mule teams of the artillery platoons, Sergeant Major Jeremiah Trask rode up. Trask commanded the foragers, who’d earned the unofficial title of “bummers.” In Goldsmith’s opinion, no one was more suited to the task. He and the non-commissioned officer shared a love of spreading misery. Because of this, Goldsmith had given command of the unit to his sergeant major rather than an officer.

Trask reined in his horse and lifted a hand in a lazy salute, strictly for appearance’s sake. A squat bear of a man, he was said to be strong enough to pick up and press the largest of blacksmith anvils over his head. The blunt features of his simian face were framed by a thick black beard that reached the middle of his chest.

“You have something for me, Sergeant Major?” Goldsmith asked.

“I got something I think you’ll like,” Trask replied.

He leaned to the side and spat tobacco on the ground. Jeremiah Trask kept a good-sized chaw of tobacco between his cheek and gum at all times, morning to night. He even slept with the plug, Goldsmith knew.

“Well, do tell . . .” Goldsmith said, feeling anticipation quicken inside him.

“Three miles over, on the river bend. We spotted some cotton fields and followed the road to a fair-sized plantation. It has a workin’ cotton gin. The house’s big enough to billet a company of the butternut grayback scoundrels.”

Goldsmith licked his lips, a quick flickering of his tongue that betrayed his excitement. His hands massaged the pommel of his saddle horn as he squeezed his thighs tight against his horse.

“The house is big?”

“I imagine we’ll find plenty of silver and there’s bound to be some gold buried,” Trask said. Then, because he knew Goldsmith really only cared about one thing, he added, “The house is two stories. So are the horse and storage barns.” He grinned under the thick beard. “That place’ll go up like Atlanta, sure enough.”

“I think I better inspect this myself before I give a report to the brigade commander.” Goldsmith rolled the lucifer from one corner of his mouth to the other.

“Yes, sir.”

The men turned their horses away from the road and the marching army. They rode out of the hills and into the river bottoms that gave way to pasture land and then cotton fields now lying fallow. After a short time, they came to the plantation.

The plantation house was palatial, made of red brick with white trim, a thing of Georgian columns and Palladian-style wings as additions to the main house. Trask’s men held the occupants at gunpoint. Off to one side, a cluster of shotgun shacks stood around a circle of sugar kettles. The slaves stood there, solemnly and silently watching the unfolding events.

Goldsmith rode his horse slowly up to the lavish front porch. On it, a tall woman with flame red hair stood stiffly waiting for him. She rested her hands on the shoulders of a ten-year-old boy who wore an expression of hatred so fierce it almost inspired a grudging admiration from Goldsmith.

Beside the woman and boy stood a teenage girl with the same red hair as her mother. She wore a simple but elegant gown that also matched her mother’s. Off to one side stood several slaves dressed in formal livery, the household servants.

Goldsmith stopped his mount in front of the woman and touched his hand to the brim of his hat. As he did so, he turned his face so she got a nice long look at his scars. His smile widened when he saw the involuntary look of revulsion flash across her own face.

“Ma’am,” he said. “I am Colonel Neville Goldsmith, XIV Corps, Army of Georgia.”

“You ain’t no army of Georgia!” the boy suddenly shouted. “Georgia fights for the Confederacy!”

“Hush,” ordered his mother as she tightened her grip on his shoulders.

“It’s all right,” Goldsmith chuckled. “I can respect spirit in a boy.”

The woman pressed her mouth into a firm line. Finally, she spoke to him, her voice as stiff as her spine.

“My name is Mrs. Scott. Patricia Scott. This is my home. What is the meaning of this incursion?”

“Pleased to meet you, Mrs. Scott. I realize it’s about dinnertime, so I’m sorry if we’ve interrupted your meal.”

“Beg pardon, ma’am,” Trask chimed in. He smirked behind his beard.

“Is it necessary to have your men point their guns at us?” the daughter spoke up.

“You’ll have to excuse them, young lady,” Trask said. “They’ve been a little on edge since we’ve marched south. What with the yellow-livered Johnny Rebs shootin’ at us and all. I reckon that goes double for your traitor scum pa, you little slut.”

Grinning, he leaned over and spat a stream of brown tobacco juice onto the porch, almost hitting the girl’s slipper-shod feet. She drew back quickly in disgust and Mrs. Scott turned to Goldsmith, her cheeks burning with anger.

“I would like you to please leave my property. At the very least, control your men, Colonel!”

Reluctantly, Goldsmith pulled his eyes away from the architecture of the plantation house. He imagined it burning, flames spilling from windows as columns of thick black smoke lifted toward the autumn sky.

He regarded the indignant Mrs. Scott with a cruel gaze. Pulling the lucifer match from his mouth, he pointed it at her.

“Pursuant to Special Field Order Number 120, and in accordance with laws of the United States of America, I hereby requisition all goods, materials, livestock, foodstuffs, or equipment capable of assisting in the military campaign to defeat the Confederacy, home of cowards and whores.”

Smirking, he replaced the match in his mouth.

“You heard the Colonel,” Sergeant Major Trask shouted at the troops. “Get to it!”

The sergeant major’s eyes burned with avarice as he swung down out of the saddle. He bounded onto the porch and lunged at Mrs. Scott’s daughter. His hand shot out and snatched a gold locket from around her slim neck. She cried out in pain and protest as the thin gold chain snapped.

“That includes all forms of currency.” Trask smiled through tobacco-stained teeth. “Like this here gold necklace.”

Her brother launched himself at Trask, a wolverine of windmilling punches. Laughing, Trask backhanded the ten-year-old across the face, knocking him to the porch at his mother’s feet.

“You damned Yankee pig!” Mrs. Scott swore. She produced a Sharps Pepperbox derringer from the pocket of her dress and leveled it at the startled Trask. “Stay away from my children or I swear to God—”

Atop his horse, Goldsmith drew his Colt Army Model 1860 in a lazy motion. As he leveled the long barrel, he thumbed back the hammer on the single-action revolver. The. 44 caliber cap-and-ball pistol roared as he pulled the trigger. A cloud of coarse black powder smoke geysered from the barrel and cylinder and hung in the air in a dark haze.

A scarlet rose of blood blossomed high on Mrs. Scott’s chest as the woman gasped in surprise. She stumbled backward and collapsed loosely to the porch floor. Her eyes remained open, fixed and staring blankly. A soft, almost gentle sigh escaped her mouth. She was dead.

“She raised a weapon against soldiers of the Union and made herself a combatant,” Goldsmith announced. “May God almighty have mercy on her soul.”

Still off to one side, the house slaves stared in shock.

The shriek that wrenched from the lips of the Scott daughter was anguished, a cry of pure animal pain. Her face went white with grief and her mouth worked soundlessly, trying to form words that wouldn’t come. Her brother threw himself at his mother’s body, desperately pleading with her to be all right.

“Mama! Mama!” he cried.

“Let this be a lesson to all present,” Goldsmith continued pompously. “Do not bear arms against the Union, under penalty of death.”

Ignoring the sobs of the children, he looked around. His men, veterans of numerous such raids, had immediately sprung into action. Milk cows and horses were brought out and tied to the back of supply wagons. They found a brace of healthy-looking mules, and Goldsmith made a mental note to assign them to the artillery corps.

Soldiers emerged from sheds with clucking chickens held upside down in each hand, or bags of cornmeal and flour over their shoulders. The blue-clad troops took stolen sledgehammers to the machinery of a cotton gin set up inside an outbuilding off from the main house. Men emerged from the main house, arms filled with silver utensils and teapots, which held no military applications whatsoever.

“These buildings are hereby deemed essential to the Confederate War effort!” Goldsmith shouted. “Burn them!”

He had to stop talking. His throat had choked up thick with his desire to see the flames let loose. He made a fist with his free hand as he holstered his pistol, trying to bleed off some of the overpowering arousal at the idea.

“Give us a chance to find more valuables!” Trask protested.

He seemed half-panicked at the thought he might miss out on the looting. A female slave in a gingham dress and white pinafore apron fell to her knees and began loudly praying.

“Billy, no!” the Scott daughter suddenly screamed.

Goldsmith turned and saw the boy racing toward him, his mother’s fallen Pepperbox in his hands, his tear-streaked face twisted with rage intense beyond his years. The girl lunged after him, trying desperately to stop the child.

Goldsmith clawed for his pistol which he’d holstered. He realized with disbelief that he wasn’t going to make it in time. The boy stopped, took the Pepperbox in both hands, and thumbed back the hammer on the little 4-barrel pistol.

Someone taught the boy to shoot, he had time to think. The observation was not without approval.

The boy was picked up and thrown to the dirt at the feet of Goldsmith’s mount. The boom of Trask’s Army Colt sounded like a cannon. The .44 caliber ball ripped into the boy’s back with unforgiving force and smashed through his spine. The child’s blood rapidly spread across the ground in a pool as he lay facedown, never to move again.

“Billy!” Sobbing, the girl threw herself at her brother, calling his name again and again.

“She’s going for the Pepperbox!” Trask hooted.

His Colt roared again. The Scott girl was flung to the side, long red hair spilling from the loose bun she wore it in. She landed hard in the dirt, eyes staring wide. Her mouth worked again, but only a bubble of blood emerged. It popped and a trickle of crimson leaked from the corner of her soft lips. By the wheezing, Goldsmith knew her lung had been shredded.

He watched the light fade from her eyes. He knew she hadn’t actually been going for the derringer. Not that it mattered.

“Well,” he told his sergeant major, “I do appreciate the assist, but the men are going to be mighty disappointed that we did away with both mother and daughter.”

Trask spat. The tobacco juice splashed the bloody backs of the murdered children. “That’s a soldier’s life for you.” He spat on the corpses again. “Besides, there’s still the darkies. Their women’ll do just fine.”

“True.” Goldsmith dismounted. Pointing at a private who’d just emerged from the front doors loaded down with several silver picture frames, a gold snuff box, and a pair of silver candlestick holders, he ordered, “Fetch me kerosene, Private.”

“Right away, sir!”

Goldsmith went up the porch steps and into the antebellum mansion. Behind him, the slaves cried in fear and outrage as the Union foragers began picking out women and girls for their use. His men saw little need to be gentle.

He walked slowly through the entryway, taking note of the numerous oil paintings, expensive furniture, and the handcrafted banister of the dramatic split-staircase leading to the second floor. He noted the heavy curtains with something like physical hunger.

“That’s what you call ‘ladder fuels’ right there,” he murmured.

Everything was so combustible, so deliciously burnable. He trembled with the anticipation of it. Trask had gotten a silk pillowcase from somewhere and was in a small, formal tea room off the main hall. He merrily stuffed anything of value he could find into the makeshift sack.

“Best hurry,” Goldsmith warned him. “I got a powerful need to burn.”

Saying nothing, Trask moved faster. He was well acquainted with his superior’s predilection for fire.

The private returned with the kerosene; Goldsmith snatched the metal can from his hands like a starving man grasping for food. The private let go and stepped back in undisguised horror. Goldsmith’s face was twisted up with lunatic joy.

“Private,” Goldsmith said.

“Yes, sir?”

“When I come out of this house, I best see every building burning.”

“What about the slave quarters?” he asked. “They’ll need—”

“Every damn building,” Goldsmith snapped.

“Sir, yes, sir!”

The man practically ran to the door as Goldsmith started splashing kerosene onto a French Renaissance–inspired settee. To his ears, the metal jug gurgled like a happy baby as he poured it across the polished walnut of a finely crafted side table. Dribbling a little trail as he went, Goldsmith wandered over to the heavy brocade curtains and liberally soaked them.

Trask had gone upstairs in search of loot. He came back down now, boots tromping loudly on the steps, a disgruntled look on his ugly face. He spat tobacco juice on the gilded wallpaper.

“Didn’t find much,” he groused. “I bet that red-haired bitch buried her husband’s hard currency somewhere. I imagine one of the house slaves knows where.”

Splashing the last of the astringent smelling kerosene on several of the oil painting portraits, Goldsmith waved him away.

“Go to it, Sergeant,” he said. “Beat the old man on the porch and he’ll talk. Failing that, get yourself a woman from the slaves.” He grinned, throwing the empty kerosene can to the floor with a clatter. “Rank has its privileges, after all.”

Sour, Trask nodded. “Girl,” he corrected absently. “I’ll pick me out a nice girl. If I’m going to eat dark meat, I want it tender.” A grudging smile tugged at the corners of his mouth as he thought about the idea.

The air was thick with kerosene fumes. The entryway would light up like a bonfire. The condensed pocket of heat would rapidly carry the flames throughout the mansion. Goldsmith pulled the lucifer from his mouth. Trask hurried from the house.

Alone with his desires, a giggling Goldsmith popped the sulfur head of the match with one hoary thumbnail. It snapped to life. Goldsmith felt a line of drool spill over his rubbery, fire-scarred lips and run down his chin.

He dropped the match and it caught with a whoosh. Fire exploded in the antechamber. It raced along rivers of kerosene, igniting furniture and floorboards. Yellow flames licked at the walls hungrily. The conflagration found the curtains, and fire raced upward. In moments the fire roared into a holocaust of heat and flame.

As the inferno raged, Colonel Neville Goldsmith stood, arms outstretched, and laughed.

Kansas, sixteen years later

Luke Jensen slow-walked his horse into the town.

A tall, well-built man dressed in black from head to foot, he rode easy and loose, just another saddle tramp wandering through on his way to no place in particular. And Craig’s Fork, judging by the looks of it, was just a step above no place.

The settlement had started life before the war as an Indian trading post, swapping whiskey, steel knives, and Sharps rifles for furs and hides. First, the trade was for beaver pelts, then buffalo skins. Then the furs and hides ran out, the end of the war pushed the frontier farther west, until the Lakota Sioux and the other tribes rose up fiercer than ever.

Craig’s Fork had always been home to rougher elements. The fur trapper brigades, mountain men, buffalo hunters, and riverboat men using the Kansas River to move goods all mixing with natives looking to trade. Not to mention the whores who serviced all comers during any boom. These weren’t the breed of men with much use for civilization or any laws that came with it.

As the trade in northern Kansas petered out, the rough but generally honest element gave way to outlaws and desperate men. Craig’s Fork became known as a place where owlhoots and gunhawks could congregate without fear of interference from the law. Justice was determined by being the quickest to kill or by making violent allies to watch your back and impose fear.

Luke had followed a trail of rumors to Craig’s Fork, searching for a wily half-breed killer named Daniel Yellow Dog who led a mix of ex-Comancheros, young braves off the Indian Territory reservations, and hardened killers on the run from the law. They raided west, into the mining and ranching towns of Colorado, then ran for the contested lands of western Kansas where they hoped fear of Sioux war parties would stop any pursuit.

Luke turned his head slowly from side to side as he rode. He saw a boarded-up assayer’s office left over from more prosperous times next to a rundown hotel that probably doubled as the local cathouse.

Those were the only two buildings made of wood. Lumber was expensive in treeless Kansas. The rest of the buildings were constructed out of sod.

Several hogs rooted through a rubbish heap. Their squeals and grunts were the only sounds except for the high-pitched whistle of the wind coming off the sea of grass. Down the passage between two sod houses, one with its roof caved in, Luke looked out onto the prairie. Dully white against the gray sky and brown grass stood two pyramids of buffalo skulls. Thousands of them. The top of the mounds had to be four stories high.

Luke had seen such sights before, but the grisly awesomeness . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...