- eBook

- Paperback

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Series info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

From Book 1:

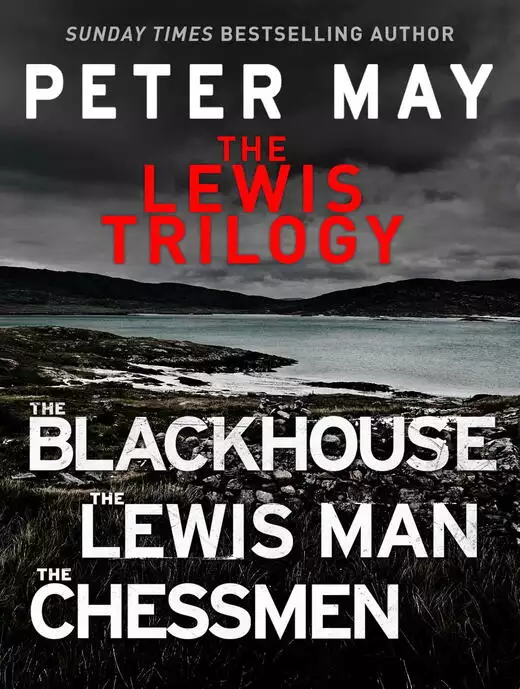

From acclaimed author and dramatist Peter May comes the Barry Award-winning The Blackhouse, the first book in the Lewis Trilogy—a riveting mystery series set on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland's Outer Hebrides.

When a grisly murder occurs on the Isle of Lewis that bears similarities to a brutal killing on the mainland, Edinburgh detective and native islander Fin Macleod is dispatched to the Outer Hebrides to investigate, embarking at the same time on a voyage into his own troubled past.

As Fin reconnects with the people and places of his tortured childhood, the desolate but beautiful island and its ancient customs once again begin to assert their grip on his psyche. Every step toward solving the case brings Fin closer to a dangerous confrontation with the dark events of the past that shaped—and nearly destroyed—his life.

Release date: December 19, 2013

Publisher: Quercus Publishing

Print pages: 1184

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Lewis Trilogy

Peter May

Unusually, there is just a light wind. And for once it is warm, like breath on the skin, caressing and seductive. A slight haze in the August sky hides the stars, but a three-quarters moon casts its pale, bloodless light across the compacted sand left by the outgoing tide. The sea breathes gently upon the shore, phosphorescent foam bursting silver bubbles over gold. The young couple hurry down the tarmac from the village above, blood pulsing in their heads like the beat of the waves.

Off to their left, the rise and fall of the water in the tiny harbour breaks the moonlight on its surface, and they hear the creaking of small boats straining at ropes, the soft clunk of wood on wood as they jostle for space, nudging each other playfully in the darkness.

Uilleam holds her hand in his, sensing her reluctance. He has tasted the sweetness of the alcohol on her breath and felt the urgency in her kiss, and knows that tonight she will finally succumb. But there is so little time. The Sabbath is close. Too close. Just half an hour, revealed in a stolen glance at his watch before leaving the street lights behind.

Ceit is breathing rapidly now. Afraid, not of the sex, but of the father she knows will be sitting by the fire, watching the embers of the peat fade towards midnight, timed with a practised perfection to die before the coming day of rest. She can almost feel his impatience slow-burning to anger as the clock ticks towards tomorrow and she has not yet returned. How is it possible that things can have changed so little on this God-fearing island?

Thoughts crowd her mind, fighting for space with the desire which has lodged there, and the alcohol which has blunted her youthful resistance to it. Their Saturday night at the Social Club had seemed, just a few short hours ago, to stretch ahead to eternity. But time never passes so quickly as when it is in short supply. And now it is all but gone.

Panic and passion rise together in her chest as they slip past the shadow of an old fishing boat canted at an angle on the pebbles above the watermark. Through the open half of the concrete boatshed, they can see the beach beyond, framed by unglazed windows. The sea seems lit from within, almost luminous. Uilleam lets go of her hand and slides open the wooden door, just enough to allow them past. And he pushes her inside. It is dark here. A rank smell of diesel and salt water and seaweed fill the air, like the sad perfume of hurried, pubescent sex. The dark shadow of a boat on its trailer looms above them, two small rectangular windows opening like peepholes on to the shore.

He pushes her up against the wall, and at once she feels his mouth on hers, his tongue forcing its way past her lips, his hands squeezing the softness of her breasts. It hurts, and she pushes him away. ‘Not so rough.’ Her breath seems to thunder in the darkness.

‘No time.’ She hears the tension in his voice. A male tension, filled at the same time with desire and anxiety. And she begins to have second thoughts. Is this really how she wants her first time to be? A few sordid moments snatched in the dark of a filthy boatshed?

‘No.’ She pushes him aside and steps away, turning towards the window and a breath of air. If they hurry there is still time to get back before twelve.

She sees the dark shape drift out of the shadows almost at the same moment she feels it. Soft and cold and heavy. She lets out an involuntary cry.

‘For God’s sake, Ceit!’ Uilleam comes after her, frustration added now to desire and anxiety, and his feet slide away from under him, for all the world as if he has stepped on ice. He lands heavily on his elbow and a pain shoots through his arm. ‘Shit!’ The floor is wet with diesel. He feels it soaking through the seat of his trousers. It is on his hands. Without thinking, he fumbles for the cigarette lighter in his pocket. There just isn’t enough damned light in here. Only as he spins the wheel with his thumb, sparking the flame, does it occur to him that he is in imminent danger of turning himself into a human torch. But by then it is too late. The light is sudden and startling in the dark. He braces himself. But there is no ignition of diesel fumes, no sudden flash of searing flame. Just an image so profoundly shocking it is impossible at first to comprehend.

The man is hanging by his neck from the rafters overhead, frayed orange plastic rope tilting his head at an impossible angle. He is a big man, buck naked, blue-white flesh hanging in folds from his breasts and his buttocks, like a loose-fitting suit two sizes too big. Loops of something smooth and shiny hang down between his legs from a gaping smile that splits his belly from side to side. The flame sends the dead man’s shadow dancing around the scarred and graffitied walls like so many ghosts welcoming a new arrival. Beyond him Uilleam sees Ceit’s face. Pale, dark-eyed, frozen in horror. For a moment he thinks, absurdly, that the pool of diesel around him is agricultural, dyed red by the Excise to identify its tax-free status – before realizing it is blood, sticky and thick and already drying brown on his hands.

It was late, sultry warm in a way that it only ever gets at festival time. Fin found concentration difficult. The darkness of his small study pressed in around him, like big, black, soft hands holding him in his seat. The circle of light from the lamp on his desk burned his eyes, drawing him there like a moth, blinding now, so that he found it hard to keep his notes in focus. The computer hummed softly in the stillness, and its screen flickered in his peripheral vision. He should have gone to bed hours ago, but it was imperative that he finish his essay. The Open University offered his only means of escape, and he had been procrastinating. Foolishly.

He heard a movement at the door behind him and swivelled angrily in his seat, expecting to see Mona. But his words of rebuke never came. Instead, he found himself looking up in astonishment at a man so tall that he could not stand upright. His head was tipped to one side to avoid the ceiling. These were not big rooms, but this man must have been eight feet tall. He had very long legs, dark trousers gathering in folds around black boots. A checked cotton shirt was tucked in at a belted waist, and over it he wore an anorak, hanging open, the hood falling away from an upturned collar. His arms dangled at his sides, big hands protruding from sleeves that were too short. To Fin he looked about sixty, a lined, lugubrious face with dark, expressionless eyes. His silver-grey hair was long and greasy and hung down below his ears. He said nothing. He just stood staring at Fin, deep shadows cut in stony features by the light on Fin’s desk. What in the name of God was he doing there? All the hair on Fin’s neck and arms stood on end, and he felt fear slip over him like a glove, holding him in its grasp.

And then somewhere in the distance he heard his own voice wailing, childlike, in the dark. ‘Funny ma-an …’ The man remained staring at him. ‘There’s a funny ma-an …’

‘What is it, Fin?’ It was Mona’s voice. She was alarmed, shaking him by the shoulder.

And even as he opened his eyes and saw her frightened face, perplexed and still puffy from sleep, he heard himself wail, ‘Funny ma-an …’

‘For God’s sake, what’s wrong?’

He turned away from her on to his back, breathing deeply, trying to catch his breath. His heart was racing. ‘Just a dream. A bad dream.’ But the memory of the man in his study was still vivid, like a childhood nightmare. He glanced at the clock on the bedside table. The digital display told him it was seven minutes past four. He tried to swallow, but his mouth was dry, and he knew that he would not get back to sleep.

‘You just about scared the life out of me.’

‘I’m sorry.’ He pulled back the covers and swung his legs down to the floor. He closed his eyes and rubbed his face, but the man was still there, burned on his retinas. He stood up.

‘Where are you going?’

‘For a pee.’ He padded softly across the carpet and opened the door into the hall. Moonlight fell across it, divided geometrically by ersatz Georgian windows. Halfway down the hall he passed the open door of his study. Inside, it was pitch-black, and he shuddered at the thought of the tall man who had invaded it in his dream. How clear and strong the image remained in his mind. How powerful the presence had been. At the bathroom door he paused, as he had every night for nearly four weeks, his eyes drawn to the room at the end of the hall. The door stood ajar, moonlight washing the space beyond it. Curtains that should have been drawn but weren’t. It contained only a terrible emptiness. Fin turned away, heart sick, a cold sweat breaking out across his forehead.

The splash of urine hitting water filled the bathroom with the comforting sound of normality. It was always with silence that his depression came. But tonight the usual void was occupied. The image of the man in the anorak had displaced all other thoughts, like a cuckoo in the nest. Fin wondered now if he knew him, if there was something familiar in the long face and straggling hair. And suddenly he remembered the description Mona had given the police of the man in the car. He had been wearing an anorak, she thought. Had been about sixty, with long, greasy, grey hair.

He took a bus into town, watching the rows of grey stone tenements drift past his window like the flickering images of a dull monochrome movie. He could have driven, but Edinburgh was not a town where you would choose to drive. By the time he reached Princes Street the cloud had broken, and sunlight swept in waves across the green expanse of the gardens below the castle. A festival crowd was gathered around a group of street entertainers who were swallowing fire and juggling clubs. A jazz band played on the steps of the art galleries. Fin got off at Waverley Station and walked over the Bridges to the old town, heading south past the university, before turning east into the shadow of Salisbury Crags. Sunshine slanted across the sheer green slope rising to the cliffs that dominated the skyline above the city’s ‘A’ division police headquarters.

In an upstairs corridor familiar faces nodded acknowledgement. Someone put a hand on his arm and said, ‘Sorry for your loss, Fin.’ He just nodded.

DCI Black barely looked up from his paperwork, waving a hand towards a chair on the other side of his desk. He had a thin face with a pasty complexion, and was shuffling papers between nicotine-stained fingers. There was something hawklike in his gaze when, at last, he turned it on Fin. ‘How’s the Open University going?’

Fin shrugged. ‘Okay.’

‘I never asked why you dropped out of university in the first place. Glasgow, wasn’t it?’

Fin nodded. ‘Because I was young, sir. And stupid.’

‘Why’d you join the police?’

‘It was what you did in those days, when you came down from the islands and you had no work, and no qualifications.’

‘You knew someone in the force, then?’

‘I knew a few people.’

Black regarded him thoughtfully. ‘You’re a good cop, Fin. But it’s not what you want, is it?’

‘It’s what I am.’

‘No, it’s what you were. Until a month ago. And what happened, well that was a tragedy. But life moves on, and us with it. Everyone understood you needed time to mourn. God knows we see enough death in this business to understand that.’

Fin looked at him with resentment. ‘You’ve no idea what it is to lose a child.’

‘No, I don’t.’ There was no trace of sympathy in Black’s voice. ‘But I’ve lost people close to me, and I know that you just have to deal with it.’ He placed his hands together in front of him like a man in prayer. ‘But to dwell on it, well, that’s unhealthy, Fin. Morbid.’ He pursed his lips. ‘So it’s time you took a decision. About what you’re going to do with the rest of your life. And until you’ve done that, unless there’s some compelling medical reason preventing it, I want you back at work.’

The pressure on him to return to his job had been mounting. From Mona, in calls from colleagues, advice from friends. And he had been resisting it, because he had no idea how to go back to being who he was before the accident.

‘When?’

‘Right now. Today.’

Fin was shocked. He shook his head. ‘I need some time.’

‘You’ve had time, Fin. Either come back, or quit.’ Black didn’t wait for a response. He stretched across his desk, lifted a manilla file from a ragged pile of them and slid it towards Fin. ‘You’ll remember the Leith Walk murder in May?’

‘Yes.’ But Fin didn’t open the folder. He didn’t need to. He remembered only too well the naked body hanging from the tree between the rain-streaked Pentecostal Church and the bank. A poster on the wall had read: Jesus saves. And Fin remembered thinking it looked like a promotion for the bank and should have read: Jesus saves at the Bank of Scotland.

‘There’s been another one,’ Black said. ‘Identical MO.’

‘Where?’

‘Up north. Northern Constabulary. It came up on the HOLMES computer. In fact it was HOLMES that had the bright idea of attaching you to the inquiry.’ He blinked long eyelashes and fixed Fin with a gaze that reflected his scepticism. ‘You still speak the lingo, don’t you?’

Fin was surprised. ‘Gaelic? I haven’t spoken Gaelic since I left the Isle of Lewis.’

‘Then you’d better start brushing up on it. The victim’s from your home village.’

‘Crobost?’ Fin was stunned.

‘A couple of years older than you. Name of …’ He consulted a sheet in front of him. ‘… Macritchie. Angus Macritchie. Know him?’

Fin nodded.

The sunshine sloping through the living-room window seemed to reproach them for their unhappiness. Motes of dust hung in the still air, trapped by the light. Outside they could hear the sounds of children kicking a ball in the street. Just a few short weeks ago it might have been Robbie. The tick-tock of the clock on the mantel punctuated the silence between them. Mona’s eyes were red, but the tears had dried up, to be replaced by anger.

‘I don’t want you to go.’ It had become her refrain in their argument.

‘This morning you wanted me to go to work.’

‘But I wanted you to come home again. I don’t want to be left here on my own for weeks on end.’ She drew a long, tremulous breath. ‘With my memories. With … with …’

Perhaps she would never have found the words to finish her sentence. But Fin stepped in to do it for her. ‘Your guilt?’ He had never said that he blamed her. But he did. Although in his heart he tried not to. She shot him a look filled with such pain that he immediately regretted it. He said, ‘Anyway, it’ll only be for a few days.’ He ran his hands back through tightly curled blond hair. ‘Do you really think I want to go? I’ve spent eighteen years avoiding it.’

‘And now you’re just jumping at the chance. A chance to escape. To get away from me.’

‘Oh, don’t be ridiculous.’ But he knew she was right. Knew, too, that it wasn’t just Mona he wanted to run away from. It was everything. Back to a place where life had once seemed simple. A return to childhood, back to the womb. How easy it was now to ignore the fact that he had spent most of his adult life avoiding just that. Easy to forget that as a teenager nothing had seemed more important to him than leaving.

And he remembered how easy it had been to marry Mona. For all the wrong reasons. For company. For an excuse not to go back. But in fourteen years all they had achieved was a kind of accommodation, a space that each of them had made for the other in their lives. A space which they had occupied together, but never quite shared. They had been friends. There had been genuine warmth. But he doubted if there had ever been love. Real love. Like so many people in life, they seemed to have settled for second best. Robbie had been the bridge between them. But Robbie was gone.

Mona said, ‘Have you any idea what it’s been like for me these last few weeks?’

‘I think I might.’

She shook her head. ‘No. You haven’t had to spend every waking minute with someone whose very silence screams reproach. I know you blame me, Fin.’

‘I never said that.’

‘You never had to. But you know what? However much you blame me, I blame myself ten times more. And it’s my loss, too, Fin. He was my son, too.’ Now the tears returned, burning her eyes. He could not bring himself to speak. ‘I don’t want you to go.’ Back to the refrain.

‘I don’t have a choice.’

‘Of course you have a choice. There’s always a choice. For weeks you’ve been choosing not to go to work. You can choose not to go to the island. Just tell them, no.’

‘I can’t.’

‘Fin, if you get on that plane tomorrow …’ He waited for the ultimatum while she screwed up the courage to make it. But it didn’t come.

‘What, Mona? What’ll happen if I get on that plane tomorrow?’ He was goading her into saying it. Then it would be her fault and not his.

She looked away, sucking in her lower lip and biting on it until she tasted blood. ‘Just don’t expect me to be here when you get back, that’s all.’

He looked at her for a long time. ‘Maybe that would be best.’

*

The two-engined, thirty-seven-seater aircraft shuddered in the wind as it tilted to circle Loch a Tuath in preparation for landing on the short, windswept runway at Stornoway airport. As they emerged from thick, low cloud, Fin looked down at a slate-grey sea breaking white over the fingers of black rock that reached out from the Eye Peninsula, the ragged scrap of land they called Point. He saw the familiar patterns carved into the landscape, like the trenches which had so characterized the Great War, though men had dug these ditches not for war but for warmth. Centuries of peat cutting had left their distinctive scarring on the endless acres of otherwise featureless bogland. The water in the bay below looked cold, ridged by the wind that blew uninterrupted across it. Fin had forgotten about the wind, that tireless assault blowing in across three thousand miles of Atlantic. Beyond the shelter of Stornoway harbour there was barely a tree on the island.

On the hour-long flight, he had tried not to think. Neither to anticipate his return to the island of his birth, nor to replay the dreadful silence which had accompanied his departure from home. Mona had spent the night in Robbie’s room. He had heard her crying from the other end of the hall as he packed. In the morning he had left without a word, and as he pulled the front door shut behind him knew that he had closed it not only on Mona, but on a chapter of his life he wished had never been written.

Now, seeing the familiar Nissen huts on the airfield below, and the unfamiliar new ferry terminal shining in the distance, Fin felt a rush of emotion. It had been so very long, and he was unprepared for the sudden flood of memories that almost overwhelmed him.

I have heard people who were born in the fifties describe their childhood in shades of brown. A sepia world. I grew up in the sixties and seventies, and my childhood was purple.

We lived in what was known as a whitehouse, about half a mile outside the village of Crobost. It was part of the community they called Ness, on the extreme northern tip of the Isle of Lewis, the most northerly island in the archipelago of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The whitehouses were built in the twenties of stone and lime, or concrete block, and roofed with slate, or corrugated iron, or tarred felt. They were built to replace the old blackhouses. The blackhouses had dry-stone walls with thatched roofs and gave shelter to both man and beast. A peat fire burned day and night in the centre of the stone floor of the main room. It was called the fire room. There were no chimneys, and smoke was supposed to escape through a hole in the roof. Of course, it wasn’t very efficient, and the houses were always full of the stuff. It was little wonder that life-expectancy was short.

The remains of the blackhouse where my paternal grandparents lived stood in our garden, a stone’s throw from the house. It had no roof, and its walls had mostly fallen down, but it was a great place to play hide and seek.

My father was a practical man, with a shock of thick black hair and sharp blue eyes. He had skin like leather that went the colour of tar in the summer, when he spent most of his waking hours outdoors. When I was still very young, before I went to school, he used to take me beachcombing. I didn’t understand it then, but I learned later that he was unemployed at that time. There had been a contraction in the fishing industry, and the boat he skippered was sold for scrap. So he had time on his hands, and we were up at first light scouring the beaches for whatever might have washed up in the night. Timber. Lots of timber. He once told me he knew a man who had built his whole house from timber washed up on the shore. He himself had got most of the timber for building our attic rooms from the sea. The sea gave us plenty. It also took plenty. There was barely a month went by when we didn’t hear of some poor soul drowning. A fishing accident. Someone in bathing and dragged out by the undertow. Someone falling from the cliffs.

We dragged all manner of stuff home from those trips to the beach. Rope, fishing net, aluminium buoys that my father sold to the tinkers. Pickings were even better after a storm. And it was after one that we found the big forty-five-gallon drum. Although the storm itself had subsided, the wind was still blowing a gale, the sea still high and angry, and thrashing at the coast. Great ragged clumps of broken cloud blew overhead at sixty miles an hour or more. And in between them, the sun coloured the land in bright, shifting patches of green and purple and brown.

Although the drum was unmarked, it was full and heavy, and my father was excited by our find. But it was too heavy for us to move on our own, leaning at an angle and half buried in the sand. So he organized a tractor and a trailer and some men to help, and by the afternoon we had it safely standing in an outbuilding on the croft. It didn’t take him long to open it and discover that it was full of paint. Bright purple gloss paint. Which is how it came to be that in our house every door and cupboard and shelf, every window and floorboard was painted purple. For all the years that I lived there.

My mother was a lovely woman with tight blond curls that she dragged back in a ponytail. She had pale, freckled skin, and liquid brown eyes, and I can’t ever remember seeing her wear make-up. She was a gentle person with a sunny disposition, but a fiery temper if you got on the wrong side of her. She worked the croft. It was only about six acres, and it ran in a long, narrow strip from the house down to the shore. Fertile machair land that was good grazing for the sheep that brought in most of the croft’s income from government subsidies. She also grew potatoes and turnips and some cereals, and grass for hay and silage. My lasting image of her is seated on our tractor in her blue overalls and black wellies, smiling self-consciously for a photographer from the local paper because she had won some prize at the Ness show.

By the time I came to start school, my father had got a job in the new oil-fabrication yard at Arnish Point in Stornoway, and he and a bunch of men from the village left early every morning in a white van on the long drive to town. So it was my mother who was to run me to school in our rusted old Ford Anglia on my first day. I was excited. My best friend was Artair Macinnes, and he was as eager to start school as I was. We were born only a month apart, and his folks’ bungalow was the nearest house to our croft. So we spent a lot of time together in those days before we started school. His parents and mine were never the best of friends, though. There was, I suppose, something of a class difference. Artair’s father was a teacher at Crobost School, where they not only took the seven years of primary, but also the first two years of secondary. He was a secondary teacher and taught maths and English.

I remember it was a blustery September day, low cloud bumping and bruising the land. You could smell the rain coming on the edge of the wind. I had a brown anorak with a hood, and wore short trousers that I knew would chafe if they got wet. My black wellies clopped against my calves, and I swung my stiff new canvas schoolbag over my shoulder, sandshoes and a packed lunch inside. I was keen to be off.

My mother was backing the Anglia out of the wooden shed that served as a garage, when a horn sounded over the noise of the wind. I turned to see Artair and his dad pulling up in their bright orange Hillman Avenger. It was second-hand, but it looked almost new, and put our old Anglia to shame. Mr Macinnes left the engine running and got out of the car and crossed to speak to my mother. After a moment, he came and put a hand on my shoulder and said I was to get a lift to the school with him and Artair. It wasn’t until the car was drawing away, and I turned to see my mother standing waving, that I realized I hadn’t said goodbye.

I know now how it feels on the day your child goes to school for the first time. There is an odd sense of loss, of irrevocable change. And, looking back, I know that’s what my mother felt. It was there in her face, along with the regret that she had somehow missed the moment.

*

Crobost School sat in a hollow below the village, facing north towards the Port of Ness, in the shadow of the church that dominated the village skyline on the hill above. The school was surrounded by open grazing, and in the distance you could just see the tower of the lighthouse at the Butt. On some days you could see all the way across the Minch to the mainland, the faintest outline of the mountains visible on the distant horizon. They always said if you could see the mainland the weather was going to turn bad. And they were always right.

There were a hundred and three kids in Crobost primary, and eighty-eight in the secondary. Another eleven fresh-faced kids started school with me that day, and we sat in class at two rows of six desks, one behind the other.

Our teacher was Mrs Mackay, a thin, grey-haired lady who was probably a lot younger than she seemed. I thought she was ancient. She was a gentle lady really, Mrs Mackay, but strict, and she had a caustic tongue on her at times. The first thing she asked the class was if anyone couldn’t speak English. Of course, I had heard English spoken, but at home we had only ever used the Gaelic, and my father wouldn’t have a television in the house, so I had no idea what she’d said. Artair put his hand up, a knowing smirk on his face. I heard my name, and all eyes in the class turned towards me. It didn’t take a genius to work out what Artair had told her. I felt my face going red.

‘Well, Fionnlagh,’ Mrs Mackay said in Gaelic, ‘it seems your parents didn’t have the good sense to teach you English before you came to school.’ My immediate reaction was anger at my mother and father. Why couldn’t I speak English? Didn’t they know how humiliating this was? ‘You should know that we only speak English in this class. Not that there’s anything wrong with the Gaelic, but that’s just how it is. And we’ll find out soon enough how quick a learner you are.’ I couldn’t raise my eyes from the desk. ‘We’ll start by giving you your English name. Do you know what that is?’

With something like defiance, I raised my head. ‘Finlay.’ I knew that because it’s what Artair’s parents called me.

‘Good. And since the first thing I’m going to do today is take the register, you can tell me what your second name is.’

‘Macleoid.’ I used the Gaelic pronunciation which, to an English ear, sounds something like Maclodge.

‘Macleod,’ she corrected me. ‘Finlay Macleod.’ And then she switched to English and ran through the other names. Macdonald, Macinnes, Maclean, Macritchie, Murray, Pickford … All eyes turned towards the boy called Pickford, and Mrs Mackay said something to him that made the class giggle. The boy blushed and muttered some incoherent response.

‘He’s English,’ a voice whispered to me in Gaelic from the next desk. I turned, surprised, to find myself looking at a pretty little girl with fair hair tied back in pleated pigtails, a blue bow at the end of each. ‘He’s the only one whose name doesn’t begin with m, you see. So he must be English. Mrs Mackay guessed that he’s the son of the lighthouse keeper, because they’re always English.’

‘What are you two whispering about?’ Mrs Mackay’s voice was sharp, and her Gaelic words made her even more intimidating to me because I could understand them.

‘Please, Mrs Mackay,’ pigtails said. ‘I’m just translating for Finlay.’

‘Oh, translating is it?’ There was mock wonder in Mrs Mackay’s voice. ‘That’s a big word for a little girl.’ She paused to consult the register. ‘I was going to re-seat you alphabetically, but perhaps since you are such a linguist, Marjorie, you’d better continue sitting next to Finlay and … translate for him.’

Marjorie smiled, pleased with herself, missing the teacher’s tone. For my part, I was quite happy to

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...