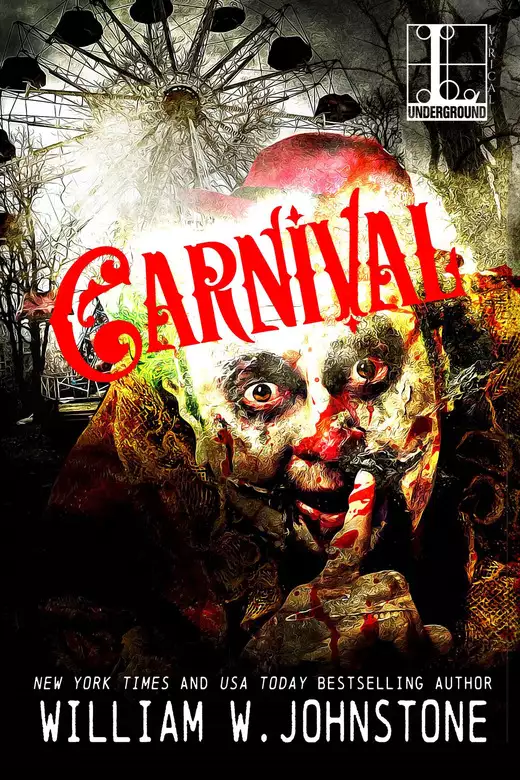

Carnival

- eBook

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The locals were ecstatic when the carnival pulled into Holland, Nebraska. They shrieked in delight on the lightning-fast rides. They gasped in shocked fascination at the chilling collection of freaks and human oddities. But all the while, piercing red eyes glared out at the townies from the shadows of the midway. Eyes that burned with vengeful hatred. Eyes that lusted for blood . . . Only Mayor Margin Holland and his beautiful teenaged daughter Linda could feel the air of “wrongness” that hovered over the fairgrounds. Then the killings began—and their worst nightmares quickly came to life. Night after night a new victim was found, his insides smoldering, his face contorted in a gruesome death mask of hideous agony. Soon, for Martin, for Linda, for the entire plagued community, there was nowhere to run and nowhere to hide. Nebo's Carnival of Dread had come to town. And the horror show was just beginning!

Release date: March 29, 2016

Publisher: Lyrical Press

Print pages: 302

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Carnival

William W. Johnstone

But that feeling? ...

Very odd. Martin couldn’t remember ever having a feeling quite like it. And he couldn’t put a name to the sensation. It was all a jumble: fear, excitement, revulsion, anticipation—a mishmash of odd emotions that he could not understand.

Why would the sight of carnival trucks produce such a myriad of emotions.

And add one more sensation, Martin thought.

Dread.

“But dread of . . . what?” he muttered.

“Getting senile when you stand on the street and mutter to yourself, dad.”

That jarred him out of his . . . whatever the hell it had been. He looked at his daughter. He had not heard her come up beside him. The sixteen year old smiled up at him. Beautiful. And Martin knew he was not being parent-prejudiced in thinking that. She was beautiful. Honey-colored hair, heart-shaped face, blue eyes. Just like her mother. And about that...

“Where is your mother, Linda? I called home and got no answer. And why aren’t you in school?”

The girl rolled her eyes and made a face. “Questions, questions.” Her father laughed at her. “Mom went down to the fairgrounds with Joyce and Janet. I saw them pass just as I was leaving the school. I came into town to get some stuff for Miss Houston.”

“The fairgrounds?” Odd. “What would possess her to do that?”

The teenager shrugged her shoulders.

“Your mother doesn’t like carnivals. She’s told me so.” A lot of things your mother hasn’t liked lately, Martin silently added. “Why would she go to the fairgrounds?”

Again, the girl shrugged. “Beats me, dad. Maybe it’s because we’ve never had one here before. They’ve been working on the old fairgrounds since spring, trying to get ready for this thing.”

Her remark triggered another odd emotion, surging from deep within him. And as with those other strange sensations, Martin did not understand the emotions or what was causing them.

“No, honey,” he corrected. “We used to have carnivals here—back when I was just a little boy. Had a big fair every year. I just faintly remember them.” He started to tell her why they had stopped having fairs, then checked himself.

Then, as violently as if he’d been punched, a strong sudden surge of memory staggered him. Martin grabbed hold of a lamp post for support. The memory came bursting forth, ugly and savage and totally unexpected.

And then it was gone; gone so swiftly he couldn’t grab any of it, only the absolute horror of it.

His daughter’s voice came through the fog circling around his brain. “Are you all right, daddy?”

He blinked, shifting his eyes. The town was all wrong. Where the hell was he? Those cars—they were all old. All of them models from back in the early 1950’s. And that boy over there, that looked like . . . No! That was impossible. He died years ago. Martin heard music from a juke box. Jesus God! He hadn’t heard that song in thirty years.

Then he looked at his daughter and thought he was losing his mind.

It wasn’t his daughter. This was some horrible-looking creature standing before him. The old hag was ragged and filthy and grotesquely ugly. A savage-looking old witch of a woman. The creature opened its mouth, exposing blackened stumps of teeth. The breath from the rotting mouth smelled of death.

Martin blinked his eyes. The hag was gone. Linda stood before him, worry furrowing her brow. Martin looked around him. All the old cars were gone. That 1950’s music no longer played.

Linda touched his arm. “Daddy?”

Martin sighed and leaned up against the lamp post. He looked around to see if anyone else had witnessed his strange behavior. Apparently, no one had. He tried a laugh that almost made it. “Tell you what, kiddo: you go on back to school. I’m going to see Dr. Tressalt. I think I’m coming down with a bug.”

“You want me to go with you?”

“No. I’m all right. It’s just a short walk. And don’t tell your mother about this, either. I’ll tell her myself.”

“OK.” She grinned at him and walked on.

Martin did not tell the doctor about his hallucinations. Not just yet. Nor anything about the strange music or his odd play of emotions at the sight of the carnival. Just that he hadn’t felt well all day and wanted a quick checkup.

After fifteen minutes of poking and prodding and temperature taking and checking blood pressure, Dr. Gary Tressalt leaned back in his chair and lit his pipe. Through a plume of smoke, he grinned and said, “Well, you smoke too much. And don’t give me any crap about physician, heal thyself. Martin, as close as I can tell, you’re as healthy as a race horse. You went over to Scottsbluff for a complete physical just last month. I read the reports, remember? Your CAT-scan was fine. You haven’t been experiencing any headaches, have you?”

“No.”

“Well, it’s awfully warm for this time of fall, Martin. People are coming in complaining of flu-like symptoms. There’s a virus going around. Hell, maybe you just got a touch of the sun. Wear a hat, damnit! Now get out of here, I’ve got sick people to see.”

Holland, Nebraska, located in the northwest corner of the state. The largest county in the state. Miles and miles of nothing to see but miles and miles. Three towns in the whole county. Holland was the largest town, but not the county seat. That was Harrisville, some fifty-odd miles to the south of Holland. Five thousand one hundred and twenty-two souls resided in Holland. Three doctors, one of them so old he only treated old friends one day a week. One small, ten bed clinic, that, surprisingly enough, was well equipped and staffed. A number of churches scattered about the town. One bank. Half a dozen juke joints and honky-tonks and one fairly decent lounge. One movie house that had been closed for years. One funeral home: Miller’s. Three very small factories that at the most employed about three hundred people. Farms and ranches dotted the area around Holland. Two rivers flowed through the county. A dozen or so small creeks.

Nothing much ever happened in Holland. The P.D. was made up of four men and one woman and the chief. Not counting the office crew. One sheriff’s deputy manned a substation.

A carnival used to play the Holland fair every year, in the fall. Last one was back in ‘54. That was the year of the big fire at the fairgrounds. Everything burned up, all the buildings, the pavilions, the rides, the trailers, the tents, everything and damn near everybody connected with the carnival. ’Bout a hundred people got all burned up, all of them carnival people. Terrible sight it was. Folks around Holland don’t talk none about the fire back in ’54. Not none at all. Mention the incident to anyone who was old enough to remember it, and they’ll just turn right around and walk off.

The fire was a lot of things, but what it was mostly, was disgraceful.

By the time the state police got to Holland, sometime around one in the morning, all the gruesome stuff had been done and was over, and boy, was there ever some stuff done that night. Holland, Nebraska made the national news for that night. Only year it had ever made the national news, before or since.

That was the night that Western vigilante justice popped back up and took care of things. Showed them goddamn carnival people a thing or two.

Ended it, right then and there.

Martin walked back up the street and paused for a moment at his hardware store, leaning up against the door jam. Most of the carnival trucks had rolled through; only a few of the concessionaires were still pulling in.

Madame Rodenska’s fortune telling truck and trailer rolled slowly up the block. Damn trucks all looked practically ancient. The truck rolled past the block of stores that the Holland family owned. The entire block; on all sides. Holland square, some folks called it. And it was a long block. The Holland family was the richest family in the county. They owned the lumber shed and the hardware store and a real estate office and this and that and the other. Martin’s greatfather had built the first store, a trading post, on the banks of the Niobrara River. Then he moved the store north about twenty miles, and founded the town of Holland.

Several more carnival trucks rumbled past, one big one with the sign NABO’S TEN IN ONE painted on the side. Damn truck was old. Martin wondered what in the hell a ten in one might be?

An elderly man came walking up the sidewalk and stopped in front of the store. “Mayor,” he greeted Martin. Martin had been the mayor since his return from Vietnam. Nobody ever ran against him and it was doubtful that anybody ever would. Job only paid fifty dollars a month and Martin never took that. Nobody except a Holland had ever been the mayor of Holland.

“Mr. Noble,” Martin greeted the man.

The elderly man waved a blue-veined hand at the carnival trucks. “Don’t like this, Mayor. Don’t like this at all. It’s a bad idea of yours, Mayor. Bad, I tell you.”

But it wasn’t my idea, Martin thought. As a matter of fact, he didn’t know whose idea it had been. “Oh, come on, Mr. Noble,” he kidded the man and smiled to back it up. “It’ll give the kids—of all ages—something to do. It’s all in fun. It’ll give the people a chance to get together and socialize.”

Noble snorted in that old man’s way. “Oh, yeah? Well, you just remember that’s what they said back in ’54, too.” He walked on up the sidewalk without another word.

Martin sighed and began the walk toward his car, parked in the lot of Holland Enterprises, about a block away and behind the main part of town. A peaceful little town. Stuck ’way to hell and gone out in the middle of nowhere. And because it was a small town, isolated, it was a fairly close-knit community. Everybody knew who was screwing whom—most of the time; who was in financial trouble; what marriages were going bad and usually why. The weekly newspaper—Martin had sold that some years back-still carried news of the local box suppers, homespun and homegrown poetry, who busted who in the mouth at the Dew Drop Inn, and in general would utterly bore anybody not from Holland.

Martin walked on. A tall man, with dark brown hair, just graying at the temples. Big hands and thick wrists. A powerful man, but very slow to anger—usually. But when he got angry, look out, for despite his wealth and education and position, Martin could and would duke it out with anybody just as fast as a cowboy with a snoot full of beer at a juke joint. And Martin would hurt you, too. Had him one of those white-hot tempers when he got the red-ass. And knew how to fight.

His shoulders were wide and his waist was still trim. Not a handsome man. His face was more interesting-looking than handsome. Rugged, was the word. Square-jawed. Dark eyes. Forty-one years old July past. ’Nam veteran. Won a bunch of medals for bravery and had absolutely no idea where they were. In the attic, probably, stored up there in cedar-lined boxes with his daddy’s army clothes and his grandfather’s World War One uniforms and a bunch of other stuff.

He wondered why Alicia had gone to the fairgrounds. She sure had been acting oddly the past months.

“Because I think it is an important event, Martin. Not that I particularly care for carnivals, I don’t—they attract the same type of people as wrestling matches. But this town is dead. Lord knows I’ve tried to bring it some culture.” That was a direct dig at him but he ignored it. Damned if he was going to get started in another argument about the little theater group. “Something is needed here, if only for a few days.”

Martin stared at her. She was lying. She always pitty-patted her hands silently together when she was fibbing, and she was fibbing to him now. Alicia had pitty-patted a lot lately. Martin didn’t know what the trouble was between them. As far as he knew, they were still very much in love, and up until about six months ago, they had enjoyed a much more than satisfactory sex life for a couple married as long as they had been.

“All right,” he grinned at her. “I’ll go along with that.”

“Fine,” she replied, a coolness in her eyes that touched her voice.

Martin fixed them drinks at the wet bar and handed one of the martinis to Alicia. “I’m getting more and more feedback from some of the older citizens. They don’t like this carnival idea at all.”

“Oh? I haven’t heard that. Is it about that stupid fire years ago?”

There were times that Martin had difficulty understanding his wife’s lack of sensitivity. “I was seven,” memory prompted the words. “I remember now. Strange how the sight of that carnival rolling through brought it back. It happened thirty-four years ago.”

Martin knew, or felt, there was something else he should recall. But he could not drag it to the light of recollection.

“And I was four,” Alicia said primly. “I recall that you acted forty when you were seven.”

Martin ignored that cut, too. He had always been a serious type of person, for the most part, even though he had a good sense of humor, when he turned it loose. “You’re fast approaching the big four-oh, kid,” he said with a smile.

“Thirty-nine forever,” she replied, but did not return the smile. “I shall never turn into some old poot.”

“Like me?”

She looked at him for a moment and then dropped her eyes.

Martin wondered, again, if nearly nineteen years of marriage was going down the toilet.

“You don’t really believe all those rumors about the fire and the cover-up, do you?” she asked.

“I sure do. Two town girls were raped and the townspeople reacted rather badly, to put it mildly. They blamed some carnival people and the carnies fought back. The fairgrounds was destroyed. Fire everywhere. All the rides and concessions and trailers and trucks of the carnival people destroyed. Some carnival people were shot, and rumor has it that some were horsewhipped just before the fire. Almost a hundred people were killed. All carnival people. By the time the state police got in here, it was all over and the townspeople stood together with their stories. Nobody ever went to jail for anything.”

Alicia shook her head. “All rumors, Martin. And I don’t believe any of them. And I do not believe it was really some townspeople who raped those girls.”

They didn’t agree on anything, anymore. But then, Alicia would never think harshly about the town. Most of the residents might not be as uppity-uppity as she thought she was, but they were still residents of Holland—although slightly beneath her.

“Well, I’ll take Dad’s word for it,” Martin countered. “He was there and we were not. Besides, he as much as admitted to me that it was a cover-up. Then he never said another word about it.”

“Was he drinking at the time?”

The question had just enough grease on it to irritate Martin. He ignored it. Martin’s father had been known to tip the jug a time or two.

“If it had been the town’s fault, there would have been lawsuits. I never heard of any.”

“Who was left to sue? Besides, dad told me the insurance company paid off the wives and kids of those killed and that was that. As far as I know. I read about it once, over at the newspaper offices, but all those accounts are gone. Destroyed by someone.”

“Now why would anybody do that?”

He shrugged his muscular shoulders. “I don’t know. To cover guilt, to bury the past, to kill the memory.” He had not told his wife about his hallucination that afternoon, or of his visit to Dr. Tressalt. He sipped his martini and asked, “Where are the kids?”

“Linda’s over at Jeanne’s, with Susan Tressalt. Spending the night. Mark has a date.”

“I thought he and what’s-her-name had broken up?”

“Betty. Yes, they did. He’s out with Amy.”

“Ah! Who’s Amy? Never mind. He flits around so much I can’t keep up with him.”

Friday evening. Most other kids and many of their parents would be all hyped up for The Big Game that night. But Holland didn’t have a football team or basketball team; hadn’t had either in years. The distances the teams would have had to travel were just too great and the school board wisely felt that money would better be served on education. But Holland did have a place for the young to congregate on weekend nights: a huge old warehouse that had been converted to a teen center. They could dance, play pool or ping-pong, have parties, or just sit and talk. And it was only loosely supervised by adults. The kids themselves kept order, and since its inception, the young people had done, for the most part, a damn good job of it.

Martin glanced at his watch. “What’s for dinner?”

Alicia smiled sweetly and smugly.

“Oh, no! I forgot.”

“That time again,” she reminded him.

Martin drained his glass and headed to the bar for a refill. He took note of his wife’s disapproving look and set the glass on the bar, returning empty-handed to his chair.

Been a lot of disapproving looks lately, he thought.

On the third Friday of each month, a half dozen couples, all approximately the same age, gathered at a home for dinner and gossip. The women enjoyed it, the men professed to hate it. But they really didn’t.

“Where are we suffering tonight?” Martin asked.

“Eddie and Joyce’s. But cheer up: next month it’s here.”

“What’s goin’ down tonight?” Jeanne tossed out the question.

Susan shrugged and Linda said, “I don’t want to go to the center, that’s for sure.”

The three girls all had that sun-tanned and wind-fresh healthy look of typical country girls. Susan grinned and Jeanne said, “What’s the matter? You afraid that Robie might be there?”

“Not afraid.” And she wasn’t. Like her father, Linda was self-assured and resourceful, and had a lot of raw nerve. “But I sure don’t want to see him. He makes me sick. He wants Suzanne, he can damn sure have her.”

“I always thought you and Robie had an agreement?” Susan said.

“Yeah, so did I. You should have seen the expression on his face when I punched open the console and found those panties in there. And they sure weren’t mine. My butt is not that big.”

The girls laughed, Jeanne asking, “Did you really hang them over his head?”

“I sure did. Then I got out of the car and walked home.”

“You tell your folks?”

“Mother. She thought it was disgusting. But she’s been weird lately.” No one commented on that. They all knew what was going on. The grapevine of the young. “I didn’t tell daddy ’cause he never was thrilled about me seeing Robie. Thought he was a wise ass. I guess he was right.”

Neither Susan nor Jeanne said: I told you so. But they both wanted to.

Jeanne rolled off the bed and dangled keys in front of her friends. “I got daddy’s truck. Come on. Let’s ride.”

Robie Grant stood in front of the teen center with several of his friends, including the unspoken leader of Holland’s answer to a gang, Karl Steele. All had agreed that it was boring as shit inside. Ping-pong. Who wants to play ping-pong?

The boys were dressed very nearly alike: jeans, boots, cowboy hats, dark shirts. And they all had one thing on the brain.

Karl Steel vocalized it. “Let’s ride. See if we can chase up some pussy.”

“Suzanne and Missy said they’d be around tonight,” Hal informed the group, “lookin’ for us. Suzanne’s got her mother’s car.”

“Let’s roll,” Karl ordered. “Get us a case of long-necks.”

And the others followed.

Martin looked at the glob of eggplant casserole the hostess had plopped on his plate. Never a picky eater, there were, nevertheless, a few things he disliked to the point of barfing.

Eggplant casserole was one of them.

To Martin’s mind, the damn stuff looked like it had unwanted visitors wandering around in it. It was almost as bad as boiled okra—and that looked like snot.

“I’m telling you, Martin, that is the absolute best food you have ever put in your mouth,” Joyce was assuring him with a smile.

Martin lifted his eyes from the crawly goop on his plate. He fought to keep from screaming.

Joyce’s face had changed: mucus ran in greenish-yellow streams from her pig-snout nose, dripping over rotting and hairy and protruding lips. She snorted and oinked and curved back her lips. Her fangs were long and discolored. Her hair was all tangled and ropy and filthy. Fleas jumped about in the mess.

“Kiss me, Martin,” she grunted.

Martin recoiled, almost dropping his plate. He blinked his eyes and the apparition was gone. The Joyce he had gone to school with stood before him, frowning, worry-lines creasing her forehead.

“What’s the matter, Martin? You suddenly went white as a sheet. Alicia!” she called as the room went silent. “Hey, girl, you’d better get over here.”

But Dr. Tressalt was there first. He sat Martin down in a chair and took his pulse. “Racing like a trip-hammer.” He looked up at Alicia. “You better take him home. I’ll get my bag and be right behind you.” He patted Martin’s arm. “You got a bad bug, my man. You’re probably coming down with the flu. The symptoms are right. I’ll see you in a few minutes.”

“I damn sure have something,” Martin agreed, standing up and moving toward the door. But for some reason, as yet unknown to him, he did not think it was the flu.

As the front door closed behind Martin and Alicia and the doctor, Milt Gilmer said, “Ol’ Martin better lay off the sauce.” He knocked back the rest of his bourbon and water. “End up like his daddy.”

Martin Holland the third got in his truck one day, drove off to the north, and never came back. That was in 1969, while Martin the fourth was doing his thing over in ’Nam. A massive search went on for days, but neither the truck nor the man was ever found. Some theorized that he was kidnapped, with the kidnappers losing their nerve and just killing him. Others felt he was drunk and drove up into the badlands and got lost. Others didn’t really give a damn what happened to him, those types of people being what they are: envious of anyone with more money and material things than they happen to possess.

Martin number four had been adamant that with the birth of his son, the numbers behind the name would cease. So the boy was named Mark. A year later, Linda came along. Alicia said there would be no more.

Good kids, most would agree. Never in any trouble, respectful to elders, and both worked for their money—unlike a lot of kids with monied parents—and made A’s in school. And both kids preferred the company of their father over the company of their mother. Which suited both parents just fine.

Back at the Holland house, with Janet coming over with Gary, Martin leveled with them all about the hallucinations he’d been experiencing. Alicia looked scornful, Janet seemed worried, and Gary did not respond at all.

The doctor took Martin’s blood pressure, his pulse—which had settled down to normal—looked into his eyes and down his throat. “Everything is normal, Martin. Like I said, I think you’ve got a bug roaming around in your innards, just winding up for the big punch that’ll put you down for a few days. You get some rest tonight and take it easy tomorrow.”

Martin shook his head. “Gary, I feel just fine! Maybe somebody slipped some acid into my drink this evening?”

The doctor sat on the ottoman, facing his friend since boyhood. “OK, buddy. Let’s pursue that line. Hey, we’re all out of the sixties, that time of great unrest and social change and experimentation. Did you ever take any LSD at good of’ U of N? Or anywhere else for that matter—like in Vietnam, to name one real good place where nobody would blame you for wanting to get zonked out? I mean, acid, or so I’ve read, can come back on a person.”

Martin shook his head. “No, I never dabbled in acid. I smoked some pot in college.” He waved his hand. “Hell, we all did—remember? Took some speed. But I never got into psychedelics. By the time I got to ’Nam, I’d been clean for over two years. I never liked grass anyway; all it ever did for me was make me hungry, horny, and sleepy—at the same time.”

Gary and Janet laughed at that. Alicia did not. That was too crude for her tastes.

“Gary, I don’t have a fever. I don’t have the sniffles. I don’t have a headache, or sore throat, or any aching in my muscles or joints. It isn’t the flu. And it didn’t start until I saw those carnival trucks begin to roll through town.”

At that, Janet walked to the wet bar and fixed a pretty good bump of bourbon.

“What’s with you, love?” her husband asked.

“Ah, well, here goes—even though you’re probably going to think I’m crazy.”

He grinned at her. “What else is new?”

Janet turned, facing the men. “Gary, I’m serious about this.”

“About what?”

“Some . . . damnit! Something pulled me to the fairgrounds today!” she blurted.

Gary stared at her. “Say—what?”

“Gary, now I told you I’m serious. Don’t make fun of me.” She looked at Alicia for support.

“Oh . . .” Alicia waved her hand. “All right. It was more something pulling me than it was Janet and Joyce. It was probably just my imagination and when I told them, it became infectious, that’s all.” She seemed anxious to dismiss the whole matter.

“Could the carnival have brought some sort of virus in here, Gary?” Martin asked.

“Oh ... maybe. But it would have to be a fast-moving sucker and everybody in that show would have to be infected with it.”

Martin stared at his wife. “You felt a pull? Would you explain it?”

“It was like, well, someone had planted subliminal suggestions in my brain. Then all of a sudden, something triggered them. I just could . . . not help myself. I had to go to the fairgrounds.”

“Weird!” Martin shook his head.

“It’s bullshit!” Gary muttered, careful that the ladies didn’t hear him say it.

The phone rang and Alicia stilled it. “Yes? Oh! Yes, he’s here. I’ll tell him. Is the boy all right? Very well, doctor. Surely.” She hung up and looked at Gary. “That was Dr. Rhodes. He was called over to the teen center. Some boy named Harold went into convulsions and then began screaming about monsters coming out of a fire. The doctor would like for you to join him.”

“That’s odd,” Gary said. “Don made it clear some time back that he doesn’t care for me at all.”

Martin stood up.

Gary looked at him. “Where in the hell do you think you’re going?”

“With you.” He lifted a hand, cutting off the doctor’s protests. “Gary, I feel fine. Look, something very odd is happening in this town. And I’m going to find out what it is. Let’s go.”

The fairgrounds lay quiet. The carnies would start putting up the equipment in the morning; but for now, they stayed in their trailers and campers—a very few in tents. The mess tent was up and open. But nobody was using it.

The road manager of the show, Jake Broadmore, and his front man, Slim Rush, stepped out of Jake’s old trailer to stand in the quiet darkness.

“Our last play-date,” Slim spoke softly and with a slight smile on his lips. He was called Slim because he was five feet, six inches tall and weighed two hundred and fifty pounds.

Jake smiled his reply.

“They got the place all fixed up real nice, don’t they, Jake?”

“Real nice,” Jake agreed.

“But it don’t look much like I remember it.”

“They changed it around some. Some rebuilding. Tell the boys . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...