- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

One would think teaching would be a quiet profession. But not in Chicago, thinks high school teacher Tom Mason when he hears that one of his students has been accused of killing his girlfriend. As a friend of the boy's family, Tom is asked to help clear him, and the more he probes, the more it seems that something sinister is going on in the usually quiet suburbs of Chicago. With the aid of his lover Scoot Carpenter, a professional baseball player, the two set out to discover what really happened that night.

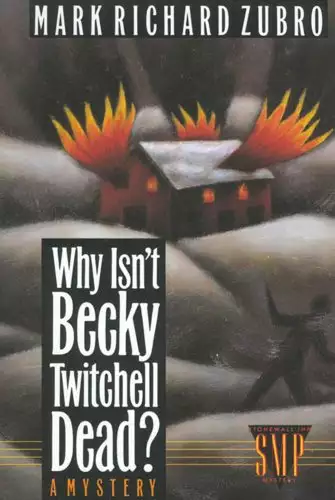

Mark Richard Zubro's second mystery for Tom and Scott is just as stunning as the first. Why Isn't Becky Twitchell Dead is a delicious satirical page-turner.

Release date: June 15, 1991

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 189

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Why Isn't Becky Twitchell Dead?

Mark Richard Zubro

1

I hate grading spelling tests. Quizzes, essays, book reports, even twenty-page research papers I don't mind. Somewhere in the seventh circle of hell, the doomed English teachers slave away for eternity grading spelling tests. No fate could be worse.

A cold Monday in late December and I wanted to go home. But I felt guilty because I'd delayed grading the damn things for over two weeks already. Under the pile of spelling tests lurked a stack of senior essays waiting to be graded.

I sighed and grabbed another stack. Scott wasn't due to pick me up for another hour, anyway.

Erratic noises drifted in from the corridor. At first, I presumed one of the janitors had been overcome with a mad desire to move a mop from one storage closet to another. Nothing ever seemed to get cleaner at Grover Cleveland High School. They built the main portion just before World War I. The school looks as if it hasn't been cleaned since just prior to World War II. A janitorial staff of even average competence could at least cover the major flaws after all these years. I gave a sour look to the back wall of my classroom. What used to be a few flakes of plaster forming charming patterns as they fell threatened to turn into a gaping entry into the science room next door. Science being even worse than spelling, I shuddered at the possible merger.

The noises grew closer. I heard loud voices punctuated by angry bellows and stomping feet.

I strolled to the door. Mrs. Trask and a male janitor approached. He saw me and grumbled about parents not being allowed in the building without permission, but that if I was here, it was probably all right. Throwing spiteful looks at her back, he retreated. I invited Mrs. Trask into my classroom. Today, she wore electric green trousers under a maroon woolen overcoat. Her thin blond hair swirled in greater disarray than usual.

She said, "Mr. Mason, Jeff's been arrested."

She had two boys--Eric and Jeff. The older, Eric, is the dumbest person I have dealt with in all my years of teaching. Forget this nice bullshit about how he was "slow, disadvantaged, socioeconomically deprived," or any other pet name. He was dumb. I knew it. He knew it. I never threw it in his face, just helped him cope. When I had him as a freshman six years ago last September, what he scrawled on a piece of paper could have been generously ascribed to a human being. By June of that year, what he wrote contained definite signs of punctuation at the ends. Most fair-minded observers would say that the enlargements at the beginnings resembled capital letters.

Even the stuff between the enlargements and the punctuation could be said to resemble words, not necessarily from any language known to me but close enough. Besides, I had more success with him than any teacher'd had in five years.

Mrs. Trask checks in as the second dumbest person I've dealt with as a teacher--not counting administrators. I suspect that she is illiterate. I've never seen her read one of the notes or letters teachers and social workers have sent her. She's approached me numerous times, asking me to explain what a note from a teacher really meant. Her good-heartedness approached the embarrassing sometimes--always remembering certain teachers' birthdays with little cakes dropped off in the office;constantly willing to help but fearful of intruding. In many ways, in bringing up her boys on her own she floundered out of her depth; but she knew what was best according to her lights and never compromised what she thought was right.

The first time I helped her bail Eric out of jail had cemented us as friends forever. I liked her barrel-shaped dowdiness. It was her, with no apologies to anyone.

Her first time in juvenile court in front of a cynical and uncaring judge had cured her of easy sentiment regarding her boys. Eric's the only kid who ever tried to take a swing at me. Mrs. Trask told me I should have decked her kid. Now he keeps my eight-year-old Chevette in more than reasonable working order.

Mrs. Trask and I had fought side by side as a succession of administrators, sociologists, counselors, and psychiatrists had tried to convince her how rotten Eric was.

"He's stupid, and he's ugly," she said at one point, "and they don't like him because he's extra work and disproves all their bullshit theories, but he's not as bad as they claim."

She was partly right. In all the years I'd dealt with slow kids, you could be dumber than a mud fence, but as long as you were a handsome boy or a pretty girl, you got passed to the next grade. If you were blond, it was even better. It isn't fair, but teachers are as human and hypocritical as everybody else.

Jeff, the child announced as arrested, I now had as a senior in my class of remedial readers. He was reasonably dumb, probably more attributable to years of laziness than to any educational deficiency. He had a wicked sense of humor. I found myself laughing at his stories and jokes more than is recommended in the university-education courses.

Feet planted solidly apart, her coat misbuttoned in haste, Mrs. Trask explained that the police had gone to their home around 3:30 that afternoon. "They slammed Jeff up against the wall, handcuffed him, and dragged him away. It was awful."

"Did they say what happened?" I asked.

"You know the police around here," Mrs. Trask said. "If your kid's been in trouble once, they always think the worst of him."

I knew Jeff had had several run-ins with the River's Edge cops, mostly concerning teenage rowdiness rather than actual criminal behavior.

Mrs. Trask showed the first signs of anger as she explained further. When she's angry enough, I've known her to be able to stand off a crew of burly police sergeants.

"They accused my boy of murder."

I drew in a deep breath, stood up a little straighter.

"His girlfriend, that Susan Warren, they found her dead. They think my Jeff did it. I told them that was stupid. They wouldn't listen to me. You've helped me with these cops before. You know how to talk to them. Could you come with me? I guess you might be busy, but if ..." Her voice trailed away.

"I'll do what I can, but you need a lawyer for this. It's more serious than the other times. I don't think we'll be able to post bail, if they'll even allow it."

"I just want to talk to my boy. Find out what's going on. See if he's all right."

I agreed to accompany her to the police station. I didn't have my car. Eric had been working on it for three days. His prognosis for its eventual return to health was not good.

I called home. Scott didn't answer. I left a message on the machine so he wouldn't come pick me up.

River's Edge is one of the oldest southwestern suburbs of Chicago, founded soon after Blue Island. From its outward appearance, you'd guess the police station was the first building erected after the founding. Dirty faded bricks--probably originally yellow--crept around the two-story disaster area. Gutters along the north side of the building hung at crazy angles. Around the outside of the building, shattered glass, broken bottles, and rusted beer cans decorated the mounds of dirty unshoveledsnow, remnants of a mid-December blizzard. The janitors here must come from the same union as the ones at the high school. Warped shutters nailed haphazardly closed over the first-floor windows added appropriate touches of dreariness. The inside continued the dumpiness scheme begun outside. The walls needed painting. Scratches and nicks beyond counting scored the solid mahogany admitting counter. The smell of mold and mildew struck offensively as we hurried in from the below-zero temperatures.

The cop behind the desk fit right in. He saw us, put down his newspaper leisurely, stood up, hitched his belt over his sixty-year-old paunch, and harrumphed slowly over to us. He walked as if his muscles were as wrinkled as his face. Retirement had to be a day or two away.

A small crowd of kids from school huddled in one corner. Among them, I recognized Becky Twitchell and Paul Conlan. They approached me and Paul Conlan asked, "Mr. Mason, what's going on?"

"I'm here to help Jeff," I answered.

Abruptly Becky yanked him away and the rest of the group followed them.

The cop refused to let us see Jeff. He couldn't or wouldn't tell us anything about the case. I asked to talk to Frank Murphy. He wasn't available.

Frank and I used to work together with troubled kids when he was in the juvenile division, before he got transferred to homicide. We'd enjoyed numerous successes with some very tough kids.

I drummed my fingers indecisively on the countertop. The cop retreated to his newspaper. Mrs. Trask looked ready for a major assault on the duty cop. The entry of a short potbellied man dressed in baggy coveralls, flannel shirt, and slouch hat forestalled her annihilation of a suburban police station.

The man ignored us, marched to the counter, slammed his fist on the top, and demanded to see whoever was in charge.

The ancient cop behind the counter rolled his eyes upward, shuffled to his feet, and began another trek from his desk to the counter. When he got there, the cop pulled at his lower lip a minute while he waited for the red-faced guy to shut up and draw a breath. After his face achieved a curious state of purple, the guy stopped. The cop asked him his name.

"Jerome Horatio Trask," was the bellowed reply, followed by more demands and outrage.

A few curious uniformed cops peered from around doorways. The old cop sighed. He pointed to us. "Wait with them," he muttered.

Trask looked where he pointed, turned several more shades of purple, and began another set of protests.

However, the cop had already begun the long journey back to his desk. Trask raved at an indifferent back for a minute. He twisted around, perhaps hunting for support, then stormed over to us.

Upon reaching us, he began verbally abusing Mrs. Trask. His comments centered on what a rotten mother she was. Mrs. Trask bore the attack with a grim frown until he called her a cheap whore and said the boys probably weren't his, anyway.

Mrs. Trask waved her fist in his face. "Get out, you son of a bitch!" Her bellow attracted a mob of cops. Before the crowd could react, he slapped her. I could have told him that was a mistake. In seconds, he lay on the floor. She sat on top of him, pummeling him none too gently into insensibility. His shouted threats turned to strangled yelps. A woman police officer got hold of Mrs. Trask and dragged her off him. With the help of the cop behind the desk, I got hold of Mr. Trask.

I'd never met Mr. Trask. Many's the time I'd gotten an earful from Mrs. Trask about what a rotten human being he was. He drank. He cheated on her. He couldn't hold a job. I could add that he didn't use deodorant. At the moment, he held the side of his jaw with his right hand; his left gingerly probed a rapidly growing blue and black mound around his left eye.

The cops led a slightly disheveled but generally unhurt Mrs. Trask to a women's room to put herself back together. We put Mr. Trask into a chair and let him moan.

Frank Murphy walked down the stairs. He wore the same dark-blue rumpled suit I'd seen him in a hundred times before. He beckoned me over. We exchanged brief pleasantries. The desk sergeant tottered over and explained the recent fracas.

"Keep the two of them apart," Frank told him. He took me to a gray, cheerless room. A scarred and battered table and two chairs sat forlornly in the center. The clanking radiator threatened to turn the room into a sauna. We sat on opposite sides of the table. He took off his glasses and rubbed his eyes. He sighed deeply, then began twirling his glasses in his right hand. He said, "Even you, Tom, are not going to be able to rescue this kid. He's guilty. We've got him cold."

"What happened?"

"We found the girl around ten last night. She was a few feet from the railroad tracks near Eightieth Avenue and One Hundred and Eighty-first Street. She'd been strangled and beaten up worse than I've ever seen. Her right arm was broken in several places and mangled as if someone had tried to twist it off. They found bloody snow all around the body. The medical examiner said she might have been raped. We found her purse nearby with her I.D. inside. She wasn't robbed. We think she must have died sometime after eight, but we're still working on the exact time." He put his glasses back on.

"That's horrible," I said. "The poor kid, who could do something that awful?"

He shrugged. "We think the boyfriend did it." The rest of the story was fairly simple. An engineer on a passing freight reported something suspicious. They sent somebody to investigate. She'd been killed somewhere else and taken to the tracks. The body wouldn't have been discovered for a while if it hadn't been for the engineer. He finished, "She was three or four months pregnant and high on coke."

"Why arrest Jeff?"

"We got bloodstains in his car and on his clothes. They match the dead girl's. He admits to fighting with her last night. He can't account for his movements at the time of the murder."

"Can I talk to him?"

"I've got to get this chaos out front settled first. His public defender was supposed to be here by now. We'll have to check with him."

The scene at the front desk needed only machine-gun emplacements to complete an armed-camp effect. A young female cop and Mrs. Trask huddled at one end of the room. Mr. Trask, a burly male cop with a tattoo of a sailing ship on his arm, and the old guy from behind the desk scowled at each other in another corner.

A dapperly attired gentleman stood between the two groups resting his arm on the counter. His bored look told the world he'd been through this a million times. He introduced himself to Frank as Jeff's public defender.

The warring camps began to make stirring noises. Frank forestalled a resumption of hostilities by asking the lawyer and Mr. Trask to join him in the interrogation room He told Mrs. Trask she would be next. Frank didn't uninvite me, so I tagged along. The lawyer and I stood against the wall on either side of the door to the room. Frank and Mr. Trask sat at the table. Frank introduced us all.

Trask burst out, "I want to know what the hell is going on here. Why have you arrested my boy? What right do you have holding him?"

"Mr. Trask," Frank began.

Trask thumped his fist on the table. "It's all his goddamn mother's fault, anyway. The kid's been trouble since he was five. She babies him. What he needs is some fast kicks on his backside. Then he'd know who was boss. That's what all these kids need today, if you ask me."

Frank said, "Mr. Trask, when's the last time you saw your boy?"

"My wife only lets me visit him once a month. I've been busy lately. I drive a truck long-distance. But that doesn't mean I don't know my boy." He thumped his fist against his chest. "He picked me last summer. He stayed three months. I knew this Susan Warren. You can't hide the kind of reputation she had. She filled him with all kinds of crazy notions. Don't get me wrong, I'm sorry she's dead, but facts are facts. He's better off with her gone."

"What kind of reputation did she have?" the lawyer asked.

"Slut. Whore. Ask any of Jeff's friends. They'll tell you."

"Who told you?"

"I don't memorize shit like that. You hear it around. You hear it enough, you know it's true."

"What crazy notions did she give him?" I asked.

"Trips alone for the two of them. Jeff used to concentrate on sports. He could get into a good college if these goddamn teachers would give him a break now and then. He's a good enough athlete to be a pro someday." He punctuated his tirades with waving fists. He told us that because of Susan, Jeff had talked about getting married right after graduation. Mr. Trask knew guys were supposed to be interested in girls at this age. He was sure his son was no virgin. Mr. Trask knew what it was like to be horny on a Saturday night. At that point, we got a leer and a loud manly chuckle as he said, "I mean, sure I wanted to get my rocks off when I was a teenager, but I kept my head. I didn't let some passing skirt keep me from my goals."

"Did you tell him that?" Frank asked.

"Sure. I've got no secrets from my sons. We get along great. We're buddies. My boys confide in me. I've been to lots of Jeff's games, as many as I could, since way back when he started in fifth grade."

For all of Mr. Trask's fabled closeness to his son, he couldgive us no account of the boy's recent activities, including the status of his relationship with Susan. He ended the conversation with demands to see his son.

Frank told him they'd interview Mrs. Trask, talk it over with the lawyer, with Jeff, and get back to him. Mr. Trask adjusted his overalls, grabbed at his crotch, and walked out the door, grumbling that there'd better be some action around here pretty soon.

Frank returned with Mrs. Trask. Her firm-set jaw gave solid evidence that she was ready to take on a Marine battalion. I wouldn't have wanted to be the Marines.

She asked quietly, "When can I see my son?"

Frank explained the entire process that would take place. At the end, he said that bail, if granted, would be extremely high.

She blanched when she heard the amount it might take to free her son, then rallied quickly. I patted her arm sympathetically.

"I want to see him," she said.

The lawyer, Frank, and the parents worked out logistics. Frank left to talk to Jeff. He came back with a puzzled expression on his face.

He pointed to me. "He wants to see you."

"Why?" I asked.

Frank shrugged.

"He doesn't want to see me?" Mrs. Trask asked.

"No, ma'am, I'm sorry. He doesn't want to see his father, either."

Mrs. Trask sat thoughtfully. Her puzzled look changed to one of confidence. "I'm willing to trust Mr. Mason, but I'd like to at least try and see him. Can you do that much?"

"If we let you see him, we'll have to let your husband in."

"I can control myself, you just keep that son of a bitch out of my way."

Sorting out who got to see whom when took some delicatenegotiations, but in fifteen minutes, six of us jammed into the room.

Jeff eyed us all suspiciously. After placing the lawyer in charge and warning the parents to observe the truce or face arrest themselves, Frank left.

Jeff wore faded jeans torn at the knees. His hair, usually moussed to spiky straightness, leaned over in sporadic sworls. He wore a black Iron Maiden T-shirt. He sat in the room's other chair. The lawyer and I remained near the entrance.

As soon as the door closed, Mr. Trask began to pace the floor and berate his son.

At first, the lawyer, a Mr. Dwyer, tried to shut Trask up. Nothing worked. Most of Trask's accusations played on the themes of "Look what this girl did to you" or "You should have listened to me."

Three times, Dwyer tried to start a reasonable discussion. For one of the rare moments in my life, I almost felt sorry for a lawyer.

Mrs. Trask eyed her husband with contempt but remained silent.

After five minutes of listening to his dad, Jeff turned to face him. He said very quietly, "Shut the fuck up."

Mr. Trask bellowed in rage and launched himself at his son. Jeff leapt to his feet, sending the chair crashing against the wall. They grappled briefly. Dwyer grabbed Trask. I held on to Jeff. Mrs. Trask didn't move. She sat with a satisfied smile on her face.

Frank Murphy rushed in. "What the hell's going on here?" he asked.

After a few seconds, Jeff ceased struggling. I released my grip on him. An angrily red Trask demanded to be left alone with his son.

"Keep that stupid shit away from me," Jeff said. "I'd rather be in a cell than be alone with him."

Dwyer stood in front of Trask, forestalling another attack.

Jeff said, "I asked to speak to Mr. Mason alone."

Mr. Trask erupted again. Jeff shoved his hands into his pants pockets and looked down. After his dad finished fulminating, Jeff said to the floor, "I'd like to talk with Mr. Mason. Just me and him."

"What about me, Jeff?" his mom asked.

Jeff looked as stubborn but less combative than he had with his dad. "I'm sorry, Mom. A little later, but I've got to talk to Mr. Mason."

She stood up, faced me. "Be kind to my boy," she said, and left.

Frank got Mr. Trask and the lawyer straightened out. When only Frank, I, and the boy were left, Frank said, "Tom, this is extraordinary even for you." He eyed me carefully.

I remembered the time we'd stood together over the body of a seventeen-year-old honor student with a full scholarship to Harvard, a popular football player who'd committed suicide minutes before we'd arrived to stop him. I read the years of trust in Frank's eyes. "Do what you can," he said, and left.

I sat on the table.

Jeff paced the room. "I hate him," he said. He stopped and turned to me. "Why did I have to get an asshole for a dad?" He picked up the chair, placed it next to the table, and folded himself into it. He looked up at me. "What's going to happen to me?"

"I don't know."

His shoulders slumped. He rested his elbows on his knees, swung his hands. "I didn't kill her," he stated.

I nodded and waited, let the silence build, then asked, "Why did you want to see me?"

"You're the only one I can talk to. I know what you did for Eric. He swore me to secrecy. He's never told anybody else, don't worry."

Over the years, some students had distorted my role in helping troubled kids. I know I have a dual reputation: one as an ex-Marine, a mini-Rambo, the other as a strict, boring English teacher. I preferred the latter to the former, and I knew which one was closer to reality. As for Eric: Outside the McDonald's on 159th Street one July evening, the cops had searched him for a kilo of crack I'd convinced him to hand over not five minutes before. I wasn't searched, and I kept my mouth shut. It would've meant a stretch in Stateville if the cops had found the drugs on the boy. I flushed the drugs down the nearest toilet while they interrogated the kid.

I decided to start with something simple. "Tell me about you and Susan, when you met, that kind of stuff."

Jeff fidgeted in the chair, tapped his foot on the floor, and began cracking his knuckles. He scratched at an ugly pimple on his neck, a few inches below his ear. Finally, feet planted on the floor, hands resting on his widespread knees, he began.

They'd attended the same grade school, but hadn't gotten to know each other until the end of sophomore year. They dated that summer, and started going steady Christmas a year ago. "At first, it was great. She didn't make me nervous. I liked being around her. She listened to my stories."

"What happened after 'at first'?"

"I guess I have to tell you because it's all connected with last night." He sighed, then continued. After a while, she'd changed, especially when she was with her friends. They'd laugh and make fun of him, tease him mercilessly. When they'd get alone, she'd keep teasing and then begin to nag and pick at him. He'd get pissed off, but she wouldn't stop. They'd end up screaming at each other. Then one time, she'd slapped him, and he'd hit her back.

He stopped the story. His eyes roved around the room worriedly, then came back to rest on mine. "Do I have to tell all this stuff?"

"Your choice. If you think I can help you without it, or if it's too embarrassing, fine. You decide. I suspect the police or your lawyer will need to hear all of it eventually."

He gulped and then went on. The first time they'd hit each other, they'd said they were sorry and had made up that night. He couldn't look at me as he told the next part. "At the end of our dates, we usually made out for a while. We did that night, but it was as if the hitting each other made a difference. That night we went ..." He stopped.

I waited a beat, then finished for him. "All the way for the first time."

He nodded and resumed. "The next weekend, I wanted to do more than make out. You know. Do it again. She said no. We had a fight. Worse than before. She tried to slap me, but I grabbed her arm. She laughed at me. She made me so goddamn mad. We wrestled. I hit her a couple more times. She cried a lot. So did I." His face turned red. He scratched at the zit again.

"Stop picking at that," I said.

He looked at his hand guiltily. "Sorry," he mumbled, then continued. "We made up and went all the way again. After a while, it got so I wanted to hit her. I knew it was wrong, but something would come over me. I wanted us to fight so I could get mad, and I knew we'd do it."

"Did you ever discuss the fights with her calmly? Not on a date? When there was a chance you wouldn't fight?"

"I tried. She said she didn't want to talk about it, threatened to break up with me. I still wanted to go out with her. I knew what we did, the hitting and stuff, wasn't right. I wanted to stop. Then on our next date, we'd go through it all again."

"Did either of you drink or do drugs on your dates?"

"We didn't do this stuff because we were drunk or high. We wanted to. The most we ever had was a few beers, maybe a couple hits of dope if somebody else had some."

"What happened yesterday?"

He drew a deep breath. "Yesterday started out okay. We went to Paul Conlan's house to watch football and party."

Paul Conlan lived the life of a cliché--star athlete in three sports, wealthy parents, handsome, popular.

"Paul's my best friend. Seven of us showed up. I wanted to talk to her. I wanted to stop the fights even if it meant no sex. Even if it meant breaking up. I couldn't take the fighting anymore."

He stood up and began to pace around the room. His untied tennis shoes flopped on his feet. He said, "I told her I wanted to leave early. She asked what for. I couldn't tell her in front of her friends. She and her buddies started teasing me. Even the guys joined in. I saw the whole thing starting all over." He leaned against the wall and thumped his fists against his thighs. "I memorized what I was going to say. But all the teasing and hassling pissed me off. When we got in the car to drive to my house, I hated her. I told her it was over between us."

"What'd she say?"

"I think she must have figured that was the excuse for that night's fight. I tried to stay calm. I told her I was serious. That the fights were over. I even pulled to the side of the road and tried to explain. She laughed at me, hit me, slapped me. I tried to stop her."

He walked over to me, head down, his hands out, pleading for understanding. "I hit her. Harder than ever before. She was unconscious. I got real scared." He sat down and told the rest. He drove to a gas station to get some water. She came around but wouldn't talk to him. Susan then spent fifteen minutes in the women's room. When she came out, she ignored him and began walking away. He followed her and offered to drive her home or to a friend's. She pushed him away, then swore at him and started swinging. He claimed he didn't touch her or even lift a hand against her. He knew he couldn't hit her. He said that by then he was crying, begging her to stop, to listen. Finally,she told him he was an asshole jock, and aimed a last kick. He tried to dodge, but she got him in the nuts. While he bent over, she laughed at him, slapped him with her purse, and took off running. He didn't see her again.

After he finished, he slumped down in the chair. I asked a few questions on details.

He drove around until one in the morning. He had no witnesses for this. He sneaked into the house, avoiding his mom, who'd fallen asleep on the couch. At home, Paul Conlan had left a message for him to call no matter when he got in. He'd called Conlan, who had a private phone in his bedroom. Paul told him they'd found Susan dead. One of the kids at the party had seen the police cars at Susan's house and called Conlan. Paul told Jeff the police were hunting for him. Jeff guessed he'd be suspected, figured he'd better not hang around the house. He thought he'd try to hide at a friend's.

I told him about seeing the kids in the police station earlier. He snorted contemptuously. "They wouldn't help last night when I needed them." He continued the story. He couldn't stay at home, he was sure the police would be there. He didn't want the hassle he knew he'd get from his mom. He drove around most of the night. He tried a couple friends. No one, including Conlan, would let him in. He watched for his mom to leave for work, then he entered the house. He didn't answer the phone or the door, but his mom went home at noon and found him. She got mad when he wouldn't talk to her, then later the police arrived.

I asked him about Susan's blood in his car.

"In the fight, she got a bloody nose. They found my blood, too." He rolled his sleeve up and showed me the gouges on his wrist and arm. "The police don't believe I didn't do it."

He claimed to know nothing about Susan's activities after she'd left him. I tried various questions from different angles, but he stuck to his story. Finally, I asked whether there was anything else he could tell me.

He hesitated. "One odd thing last night. After I called Paul, before I left the house, Becky Twitchell phoned. She almost woke up my mom. Becky told me to keep my mouth shut about the kids at the party. She warned me not to tell. You can't be too careful with Becky. Bad things happen to people who cross her."

If they ever held auditions again for the Wicked Witch of the West, Becky would win. If a teacher strangled Becky in front of the entire student body at high noon, as long as there was one teacher on the jury, they'd never vote to convict. If there was a school rule she hadn't broken, I didn't know about it. Her mom is president of the school board. This explains a great deal.

The teachers hate Mrs. Twitchell almost as much as they hate Becky. As a freshman, Becky had complained to her mom about one first-year math teacher. Becky had made the class a total hell,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...