- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

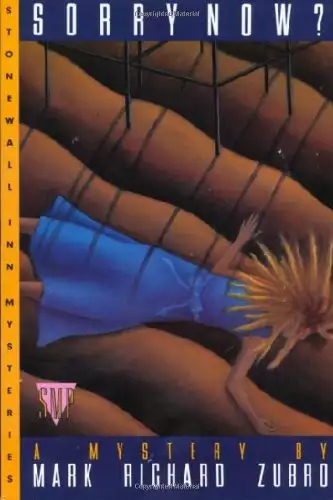

Synopsis

Publishers Weekly calls Mark Richard Zubro's Sorry Now: A Paul Turner Mystery? "compelling and even urgent."

While in Chicago, right-wing televangelist Bruce Mucklewrath is attacked and his daughter killed. Sensing a potential time bomb, and with Mucklewrath creating great pressure, the police brass assign the case to Detective Paul Turner whom they trust with sensitive matters. During their investigation, Turner and his partner discover that other right-wing bigots have been suffering odd attacks, and they begin to suspect a conspiracy of vengeance, perhaps even from the gay community. This is an uncomfortable thought for Turner, who is himself gay, but when Turner is attacked and his two sons threatened, he has to enlist the help of people in his close-knit neighborhood, as well as his contacts in the gay world, to find the solution in time.

Release date: October 15, 1992

Publisher: St. Martin's Publishing Group

Print pages: 192

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Sorry Now?

Mark Richard Zubro

ONE

Paul Turner padded downstairs to his son Jeff's bedroom. Sunlight and birdcalls streamed in through the open window. The gauze curtains brushed against his hips as he stepped over his son's crutches. He paused, as he always did for a brief moment, to watch his son sleep. He noted the rise and fall of the thin chest, let his eyes rove over the shaggy hair. Neither Jeff nor his brother, Brian, believed in haircuts. Even shampooing their hair when they were little had been a major battle. He checked the leg braces on the floor and then ran his eyes over the catheterization equipment on the nightstand. Everything in place. Jeff stirred and turned on his stomach, the covers slipping down to reveal the years-old scar on his back. Paul called Jeff's name and touched his shoulder. Only another week of school before Jeff could sleep late. Paul shook the shoulder gently. Jeff's ability to sleep through even the worse noise still astounded his father. Jeff opened an eye and his dad left; hearing the shower start on the second floor, he knew Brian was up.

Paul returned upstairs to his own room to finish dressing and continue his morning routine. Fifteen minutes later, after carefully knotting his tie, he went to the safe in the closet andunlocked it. He took out his gun, checked it carefully, strapped on his holster, and grabbed his wallet with the star in it.

Jeff sat at the kitchen table reading a library book. Brian, hair still damp, stood at the stove. He poured beaten eggs into the pan and sprinkled cut-up spinach onto them. He asked, "There's a party at David's tonight. I'll be out late. Okay?"

Paul took the orange juice out of the refrigerator and placed it on the table. He eyed his sixteen-year-old son critically. "Who's supervising the party? Remember you have to pick up your brother by midnight. I'll be late."

"Dad! Nobody's going to do drugs or drink. We're not going to have an orgy on the carpet!"

"What's an orgy?" Jeff asked.

"When people enjoy themselves more than they imagine," his father answered the ten-year-old. He turned back to Brian. "Are David's parents going to be home?"

His son grinned at him, "I think they're the ones supplying the condoms."

"I know what a condom is," Jeff said. "I saw it on TV."

"As long as your bother knows, is what's important," Paul said.

Paul squeezed behind Jeff's chair to get to the drawer with the utensils. He found the silverware, placed it on the table, and grabbed a coffee cup. The kitchen sat at the back of the house with a window overlooking the cluttered back porch and small urban back yard.

Brian's voice squeaked as he began to speak. "I promise to clean the basement and the attic the first day of vacation."

"You have to clean them anyway. You usually don't resort to bribery until after you've whined for ten minutes. You in a rush?"

"My whine quotient got used up talking to Coach yesterday. He expects us to do a full workout in this heat, besides regular practice."

"Just remember to drink lots of fluids and you should be okay," Turner said.

Paul and his sons ate breakfast together every weekday. Theyrose a half hour early to share at least the one meal together, to talk, compare schedules, settle family squabbles. Paul Turner's workday started at eight thirty, and as much as he tried to stick to a set schedule, the amount of overtime required of a detective in Area Ten of the Chicago Police Department made this almost impossible. In spring Brian's baseball practice kept him out until six most nights. Jeff's schedule varied because of his physical therapy. Paul wanted them together at least once a day for a meal one of them cooked. They each took a week and rotated assignments. One cooked, one set the table, one cleaned up. Jeff's meals were, understandably, simple. The kitchen had special chairs, hooks, and pulleys to aid Jeff, although Turner stood ready to help and often assisted Jeff if things got complicated.

On the car radio on the way to work, the announcer gave the temperature as eighty-one degrees. The National Weather Service predicted another record high temperature in Chicago, with little chance of a break in the early-June heat wave.

As usual, the detectives in Area Ten mumbled their way through Friday-morning roll call. The structure they sweated in was south of the River City complex on Wells Street, in a building as old and crumbling as River City was new and gleaming. Fifteen years ago the department had purchased a four-story warehouse scheduled for demolition, and decreed it would be the new Area Ten headquarters. To this day rehabbers occasionally put in appearances. In fits and starts the building had changed from an empty hulking wreck to a people-filled hulking wreck. The best that could be said about it was that the heat usually worked in winter. The worst was that it had absolutely no air conditioning.

Sergeant Felix Specter had been through roll call with some of them over a thousand times. They rested their back ends on folding chairs. The bulletin board hung to the left of the chalkboard in front of the room. Messages crammed the entire surface. Turner glanced over the items on the board: the usualannouncements of retirement parties and a few notes from the Fraternal Order of Police, the cop union in Chicago. Next to the bulletin board hung the chart of acceptable hair lengths in the department.

Later in the squad room, Paul joined his partner, Buck Fenwick, at the coffee machine. Buck was on another diet. They'd been partners five years and Buck had gained an average of eight pounds per year.

"Double and triple fuck," Buck swore as he shook the last grains of sugar from a mangled box.

Turner said, "I thought you couldn't have sugar on the new diet."

"I get ten grains a cup." He shook the box again.

Ten years ago the Chicago Police Department created Area Ten to combat the rising wave of crime along Chicago's lake front. It ran from Fullerton Avenue on the north to Fifty-fifth Street on the south, and from Lake Michigan west to Halsted Street.

Turner took his black coffee, strolled to his desk, and began sorting through files, active cases to be pursued today, leftover paperwork from an ax murder in Grant Park. From the start Paul had been sure it was the deranged father-in-law who'd done it. They had caught the guy two nights earlier trying to retrieve the ax from the bottom of Buckingham Fountain. Unfortunately for him the police had found the ax already and had set up watchers in case he returned.

Buck Fenwick arrived at his desk, which was front-to-front with Turner's, and threw himself into his chair. Turner heard the telltale squeaks of protest that told him the chair had about another week and a half before Fenwick's bulk would crush it to the floor. Fenwick perched the cup on a stack of files, as he always did. Coffee sloshed out, as it always did. Turner handed him a napkin, as he usually did. "Double fuck," Fenwick swore, mopping it up.

Turner liked being partnered with Fenwick. They could hardly have been more different. Turner's dark haired five feet eleven inches contrasted with the blond bulk of his rapidlybalding friend. Fenwick didn't sweat the small stuff. Turner appreciated his casualness.

Sergeant Specter bustled into the squad room, his white shirtsleeves already rolled up past the elbow, revealing the angry red flaking that started with the first seriously humid days of the Chicago summer. No doctor had been able to cure it and neither mounds of salve nor special-ordered ointments seemed able to control it. He slapped a message on Turner's desk.

"Oak Street Beach, and you better hurry." He moved off quickly.

Turner and Fenwick took one of the old unmarked Plymouths from the lot. They crossed Congress Parkway and turned left to descend to Lower Wacker Drive, a little-used but extremely efficient method of crossing the Loop without the usual hassle of masses of pedestrians and blocks of jammed traffic. Fenwick drove with a cab driver's abandon. He claimed city driving was just like bumper cars when he was a kid going to carnivals. Turner always hooked his seat belt and spent the time watching the passing scenery. They parked illegally across from the Drake Hotel and took the pedestrian underpass to the beach.

Near the children's play area, just north of Oak Street Beach about fifty feet from the LaSalle Street off-ramp, the beat cops had roped off an area one hundred by one hundred feet. Joggers slowed to crane their necks at the mob of cops trudging around in the sand next to the jungle bars. As he plodded through the sand, Turner observed a tall blond man who looked to be in his mid-sixties sitting on a park bench. The man let tears stream from his eyes, making no attempt to stanch the flow. He occasionally wiped at his upper lip with the back of his hand.

A beat cop named Mike Sanchez met Turner and Fenwick half way across the sand. Turner knew Sanchez and liked him. Recently Sanchez had taken the detectives test, and Turner asked him if he'd gotten the results. He got a shrug and a no.

Sanchez explained. "We got big problems here. This guy," hejerked his thumb toward the crier," is the Reverend Bruce Mucklewrath."

He hardly needed to say more. Not only did Mucklewrath have a national reputation, but his distinguished face had been plastered all over every TV station in the Chicago area for the past three weeks. He was on a campaign fund-raising and religious tour, gathering money from and speaking to the faithful. He'd just finished his first term as senator from California, and was in the middle of a brutal campaign to get himself reelected.

Prior to his election, his fame had rested securely on a far-flung spiritual and financial empire. His critics scoffed at the missions he funded for the homeless in every major city in the country, saying they were only for show. The voters in the state of California had elected him senator in a freak three-way race. The Republican and Democratic candidates had split the middle-of-the-road and minority votes almost evenly. The far right had spent thirty million in the most expensive senatorial campaign ever. The reverend, as an independent, had won by slightly less than two thousand votes out of eleven million cast.

Turner had read a couple of Mucklewrath's speeches and followed his career, as had most Americans. He didn't like him. As a rookie cop, Turner had learned to put his emotions on cruise control during an investigation. He'd lost his temper a few times after becoming detective. The last time was when he'd gone after a drug dealer who'd murdered an entire family--father, mother, and three kids all under the age of five--because the father was behind in his payments. His temper outburst had caused the dealer to have an unfortunate encounter with a brick wall. The defense attorney used it to escape, his client getting a penalty only a little more inconvenient than a trip to the dentist. Turner had learned: add your temper to personal feelings and nowadays you lose a perfectly good bust.

"What happened?" Turner asked.

"We got a dead body over there." Sanchez pointed to a jungle-gym set. "The reverend hasn't been able to tell us much. Pretty broken up. We do know it's his daughter."

As the three of them stepped toward the children's play area Sanchez said, "We got a visit from one of the people in the mayor's office. This is going to get political."

"I suppose it will." Turner sighed.

Close up now, they saw the mass of twisted blond hair streaked with red splayed out on the sand. The body lay six inches from one of the metal struts supporting the jungle gym. Sunlight gleamed on the metallic surfaces of the eight-foot-tall children's play set. Remnants of the disaster clung to the light-blue summer dress the victim wore. Bits of brain, blood, and gore covered the sand next to the nonexistent face.

Sanchez pointed to a small cluster of people thirty feet to the north of the body. "They're as close as we've got to witnesses. No one saw the actual shooting. They all showed within minutes."

Fred Nokosinski was clambering up the play set to get pictures from above. A bearded dwarf, Fred always took the crime-scene photos. He grunted a hello down toward them. The white van with CHICAGO CRIME LAB printed on the side had been driven over the sand to the crime scene. Paul saw a tall, young, new guy he didn't know fussing with materials in the back of the van. Two feet from the body Sam Franklin, the head of this crime-lab unit, knelt in the sand. He held a thin piece of screen boxed by four wooden slats. Through this he carefully sifted grains of sand, hunting for evidence. Two other men around the body engaged in the same activity.

Sam rose and greeted the detectives.

"Be a miracle if we find anything in this sand," he said. "You guys are going to be up to your tits in politics in this one. Know who the dad was?" Turner thought he sounded altogether too confident and cheerful.

Turner nodded. "Any idea what happened?"

"I can get you all the technical details later. For now, somebody blew her away. No weapon around." He nodded toward the lake. "Lots of room to toss a gun." He glanced toward Mucklewrath. "They haven't been able to get the preacher to talk, which I guess is unusual for him." Sam shrugged. "I don't envy you guys."

"We'll call you later," Turner said. He and Fenwick walked tothe bench and sat on either side of the Reverend Mucklewrath. Turner eyed him warily. One of the first lessons they taught you was, always watch the family most carefully. In all likelihood, if one of them hadn't done it, one of them knew something about why.

Turner watched the man pulling in vast gulps of air and exhaling them noisily. Sand covered his black wing-tip shoes, the knees of his pants, and his suit coat up to the elbows. His clothes were spattered with blood and gore, concentrated mostly on the front of his shirt and suit coat, probably where he'd held his daughter. Paul pictured the man holding his lifeless child. As the father of a child with spina bifida, he'd held Jeff many a night when he didn't know if the boy would survive an operation. He didn't want to imagine his son dying.

Turner said, "Sir, I know it's difficult, but we need to talk to you, ask you some questions."

After mopping his face with a pink handkerchief, and still breathing erratically, Mucklewrath said, "I want the killers punished." He gasped for air and shuddered. "I want them punished in such a way that they will pay forever, here and in hell."

"Yes, sir, I understand," Turner said. "You could help us catch them if you could answer a few questions."

"Who would want to hurt her? Such a good and beautiful daughter. Her angelic smile. She laughed so beautifully. So full of life and hope."

Turner said, "Please, sir, a few questions."

He mopped his face again and stuck the hankie in his suit-coat pocket. "All right."

"Could you tell us what happened?" Turner asked.

Speaking with numerous pauses and gasps for air, the reverend told them that he liked to bring his daughter on his speaking trips. His wife usually came, too, but this time had stayed to oversee some changes in the new university their ministry was building in Laguna Beach. Today the Reverend Mucklewrath didn't have a meeting until ten. So when his daughter expressed a desire to go out together for an early walk, they chose a stroll along the shore. "We've been here before. It seems so safe in themiddle of Oak Street Beach. All the people going by on Lake Shore Drive."

A few tears escaped his eyes. Paul thought they were real, but he'd discovered over the years that some killers were often completely overcome with grief after they'd murdered.

The reverend continued, "She was so happy, so content. We talked about her new role in the upcoming campaign. She'd finished her sophomore year in college and wanted to spend the summer helping me. She had plans and dreams. Real ideas to help out. A father couldn't expect more from a child." As he finished the sentence he broke down sobbing.

The cops waited patiently. Turner noted that the bench sat in a grassy area about ten feet from the jungle gym and about thirty feet from the shore. The leaves of a few trees let in the dappled sunlight on what should have been a peaceful patch of quiet earth. None of the bathers who would cram the beach by noon were around to see horror on this beautiful morning.

The reverend resumed. "She's been my joy since she was born." He used his sleeve to wipe the tears on his face.

Turner understood. He'd almost lost Jeff several times when the boy was small. He knew the fear and sorrow.

Finally Mucklewrath started again by saying that he hadn't observed many people on the nearly deserted beach. The three men had come up from behind them, so he hadn't seen or heard them.

"Two of them grabbed me. One gripped me around the neck. I tried to struggle. He tightened his arm. I nearly passed out. Another one held a knife to Christina's throat while grabbing her from behind. I thought they meant to rob us. Then one of the men holding me pulled out a gun. He swung it ..." He paused and gasped for breath, then continued. "He swung it toward Christina. She couldn't see the gun from the way the evil piece of filth held her. Then I saw ..." His voice fell to a whisper. "I'll never forget it."

Turner expected an emotional crack, but the reverend talked on almost as if he were in a trance.

"The one holding me said, 'This is your last look at happiness.'The other raised the gun. Aimed. The silencer muffled the noise. The bullet ..." He stopped for several moments. "I struggled mightily. I tried to cry out. The one holding me squeezed my throat tight enough so that I passed out. The last thing I remember him saying is 'Sorry now, aren't you?' They left enough life in me so I could come back to this horror."

"We're sorry for your loss," Turner said.

The man nodded. Turner and Fenwick waited for him to regain control.

Finally Fenwick asked, "You're sure he said, 'Sorry now, aren't you'?"

"Yes."

"Why would he say that?"

"I don't know."

"Can you tell us more about your attackers?" Fenwick asked.

The reverend looked at Fenwick through bleary eyes. "It all happened so quickly," he said.

"Were they white, black, Hispanic?" Turner asked.

"White, I think. They had masks on. It was hard to tell much about them."

"Do you remember anything about what they wore? Jogging outfits or dress clothes?"

"They wore street clothes. I think one wore dress pants, the others jeans. I think they had on sport coats. Dark colored. I don't remember."

"Shoes?"

"I didn't notice. Most of the time I was looking at Christina and talking or listening to her."

"Even the smallest thing," Turner prompted. "Maybe the color of hair?"

Mucklewrath thought a minute. "No. Sorry. I didn't pay attention."

Turner knew the answer to the next question, but he knew he had to ask it anyway. "Reverend, do you have any enemies?"

Bruce Mucklewrath's answer to such a question could have filled a Chicago telephone book, white and yellow pages combined. Time magazine had done a cover story about thedeath threats that became a central theme of the Reverend's California campaign. He'd viciously attacked any group even slightly to the left of his own positions.

The preacher said, "Doing the Lord's work can cause unreasoning hatred in those who haven't yet seen the light."

The sanctimoniousness of the reply grated on Turner's nerves, but he didn't let this show as he said, "I meant anyone in particular. Any specific threats?"

"No. None. I can't believe anyone would do such a thing."

They asked numerous other questions, but got no further information. Fenwick said, "That's all for now, Reverend. It we think of anything, we'll get in touch."

"Catch them, punish them. I can feel the Lord calling for vengeance."

They left after assuring him they'd do their best to catch the killers.

"He's gotta know more," Fenwick said.

"Give him time," Turner said. "We can get an enemies list and check it to see if anybody's in town. We can find out if anybody in Califorina's got a comprehensive list of the threats, what they found, if anything. Let's try the witnesses."

As they walked up the beach Turner was grateful for the coolness of the nearby water. He could feel sweat trickling down the back of his neck.

Fenwick said, "I wonder if anybody on the Drive saw anything as they went by."

"The guardrail pretty much blocks the view," Turner said, "and it's over fifty feet away. Who'd be paying attention during rush hour? Probably nobody, but we'll have to check it out, if we can."

"They must have been cool heads," Fenwick said, "to try something this bold. How'd they know they wouldn't be interrupted or chased? Their exits are limited. Up or down the beach, through the tunnel the way we came in, or a dash across six lanes of traffic on the Drive." Fenwick paused. "Maybe they had a boat waiting," he suggested.

"Let's try our witnesses," Turner said.

The meager group of four witnesses chatted sporadically witheach other. A uniformed police officer hovered nearby so none of them would give in to the urge to walk off.

The two women in their fifties, dressed in red shorts, walking shoes, and Chicago Bears T-shirts, and wearing Walkman radios, explained that they hadn't heard or seen anything, but had come upon the unconscious reverend and tried to revive him. One woman had bright red hair that didn't look dyed. The other had black hair that could only have come from a bottle and which she had tied back in a ponytail.

"We didn't see the body until a minute later," the black-haired one said.

"The sand kind of hid her," said the red-haired one.

"We were shocked. I never want to see such a thing again," the first woman said.

"Which way did you come from?" Turner asked.

"Lake Point Towers," said the redhead. They hadn't passed anyone on their walk up from the south.

Neither had approached the body. They hadn't seen any boats in the water. After a few more questions, which elicited no further facts, Turner and Fenwick moved on to a young jogger who couldn't have been much over eighteen. His blue and white Chicago Cubs T-shirt still clung to his torso in wet patches. His gauzy jogging shorts fit snugly around his ass and crotch. Paul doubted he wore a jockstrap, but thought he probably should have.

The boy's name was Frank Balacci. "I was jogging down from Fullerton. I saw the women and then I spotted something near the kids' play area. I walked up to the body." His face turned pale as it must have done at the time. "I didn't get close, but near enough. I tossed my cookies into the lake. I left the body and came to help the women here. Then I ran to call the cops." He hadn't noticed anyone suspicious on his run from the north, definitely not three men together. He'd had a clear view of the lake as he jogged. "Definitely no boats around anywhere," he told them.

"That eliminates three directions," Fenwick said as they turned to the last witness.

This was a tall thin man with completely gray hair. Even onso warm a day, he wore a sweater and a white shirt buttoned to the collar. Two Afghan hounds sat placidly on either side of him, their leashes held firmly in his right hand. His lisp had to be practiced. Turner noted a large gap between the man's upper two front teeth.

"I'm a retired architect," he explained. "I walk along here every morning at precisely this time. Look at the skyline behind you. I had a hand in designing a significant number of the buildings you are looking at. I own small portions of many of them."

His name was Alexander Polk and he'd seen something. "I'd just emerged from the underpass by Oak Street when these men walked past me. I knew something was furtive about them. They moved too fast to be out for a pleasant stroll. They weren't dressed for jogging, and they weren't any of the regulars down here. Very suspicious." He'd paid them little heed after that. Polk could only tell the police he thought they all had dark hair and were white. He couldn't remember the color of their clothes and hadn't stopped to watch where they went. He hadn't seen any others. Polk had then proceeded up the beach and come upon the scene as described by the others.

None of the witness had seen anyone else. The beach, sparsely traveled at this hour on a weekday, didn't lend itself to eyewitnesses; that was probably why the killers used this time to strike. After taking down the witnesses' addresses, Turner and Fenwick told them they could go.

Fenwick looked at the high-rises that lined Lake Shore Drive. He sighed despondently. "Maybe someone up there saw something."

"We'll need to get some help canvassing all those places," Turner said.

The case sergeant, who rarely showed up at a crime scene, approached them from across the sand. Prominent people drew official concern the way shit draws flies. Turner treated each case the same, or as nearly as he could. He figured they were all crimes to be solved. It shouldn't matter who was involved, whom he liked or disliked. He had a job to do.

The sergeant looked concerned. This was the face he usedwhen out in public where a reporter or a civilian might see him. He delayed their investigation with exhortations to work hard, cover all bases, interview everybody.

With this rush of interest, Turner got him to commit an extra four people for the canvass of the high-rises.

The crowd on the beach had been reduced to a few of the desperate or bored, hoping for some kind of excitement. By this time the pictures had been taken, the schematic drawing of the scene had been made, the fingerprints on the jungle gym had been lifted. A team of men working in large roped-off squares of beach carefully sifted through the sand hunting for any kind of evidence that might lead to the identity of the killers. They would be doing it for a fifty-foot radius around the scene. Turner didn't think they'd find much.

Turner tapped his pen on his standard-issue blue notebook. He'd set in clean paper this morning before he left. Seeing eight people grouped around the Reverend Mucklewrath, he nudged Fenwick, and they strolled over.

The reverend stared fixedly at where police personnel worked around his daughter's body.

As they neared the group, Fenwick said, "This had to be extremely well planned, or these guys were really lucky. A jogger, a casual stroller, anybody could have come along and seen everything, or the good reverend is making the whole story up."

"I'd thought about that," Turner said. "We'll have to see, although our last witness confirms the three suspicious characters."

When they got within ten feet of Mucklewrath, a tall man in a dark-gray suit and tie left the crowd and walked to them. "I'm Dr. Hiram Johnson, the spokesperson for the Reverend Mucklewrath. If you need to know anything, I'll be able to help."

Fenwick said, "We'll need to talk to all the people staying with the Mucklewrath party."

Dr. Johnson patted the front of his buttoned suit coat. "It is much more normal for me to deal with the public and any questions."

Turner eyed the man's bald head, which gleamed in the bright June sunlight. Johnson looked totally comfortable in his suit.Turner wished he could take off his own sport coat and loosen his tie, but especially take off his shoes and socks. He could feel the grit of the sand that had seeped into them.

"Dr. Johnson," Fenwick said, "this is a murder investigation. We talk to whoever we want whenever we need to."

Dr. Johnson did not become indignant as Turner expected. Instead he installed a bland unctuous look on his face. The man said, "I did not mean to imply that I was interfering. I simply meant to be as helpful as possible. Anyone in the Reverend Mucklewrath's organization is ready to assist the police at this tragic moment."

"Where were you this morning, Dr. Johnson?" Fenwick asked.

"In my hotel room. Making phone calls for the next cities the tour will be in. Setting up last-minute details."

"Can you provide us with a list of those calls?" Fenwick asked. They could get them from the hotel easily enough.

"I'd be happy to, Officer."

By the time half Fenwick's question was asked, Turner knew his partner didn't like the guy either.

If Dr. Johnson noticed, he didn't let on.

"Where are you all staying?" Fenwick asked finally.

Johnson pointed across Lake Shore Drive to a building several doors down from the Drake Hotel. "We have several suites at the Oak Street Arms, all interconnected."

"Do they look down on the beach here?" Fenwick asked.

"Yes. And no, I didn't happen to look out. As far as I know, no one did. We didn't learn of this until a policeman came up a few minutes ago. We all rushed down here."

"Do you know who might have wanted to hurt the Reverend? Someone who held a grudge?" Fenwick asked.

Dr. Johnson spread his hands out flat, palms up. He said, "The Reverend had many enemies. I'm sure we'll have a statement available later. There are many servants of Satan who are capable of great evil."

Turner said, "I remember the Time magazine article on the threats in the Senate campaign. Can you tell us anything aboutthem, especially if any new threats had been made in the past week or so?"

"None that I know of. You'll have to talk to Donald. He deals with the Reverend's security." They asked Johnson a few more questions, but he was no further help.

Johnson beckoned over another man. He introduced him as Donald Mucklewrath, son of the preacher and head of security.

Donald Mucklewrath wore an impeccable gray suit and a grave frown. He dismissed Johnson with a nod, then shook hands with both cops. The son had to be in his thirties.

"We're sorry about your sister's death," Turner said.

"Thank you," he said softly. Tears sprang from his redrimmed eyes.

Fenwick said, "We realize this is a dif

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...