- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

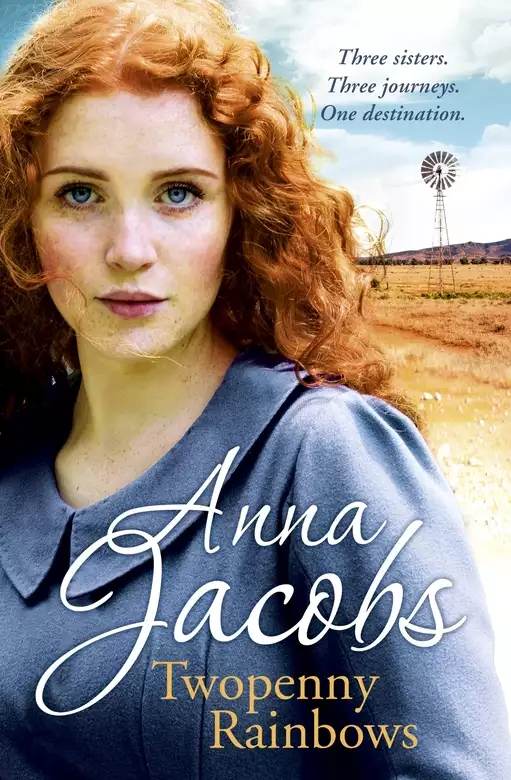

The new Anna Jacobs saga continues the story of the younger sisters of Keara Michaels, the heroine of A Pennyworth of Sunshine, following their fortunes from 19th-century Ireland to the brave new world of Australia.

Three sisters. Three journeys. One destination.

In 1863 the authorities send Irish orphans Ismay and Mara to Australia against their will. Just when they thought it couldn't get any worse, on arrival they're separated from one another. While Ismay is forced to take a job as a maid miles away in the country, Mara must stay in the care of the Catholic mission.

Desperate to be reunited, they both run away, but Ismay soon runs into danger out in the bush. She is saved by Malachi Firth, but although he's attracted to her, he doesn't want to be encumbered with a wife.

Meanwhile, their elder sister, Keara, has not forgotten them. But she has had her own struggles to face, and by the time she reaches Melbourne in search of her sisters, she finds that the trail is cold. Danger continues to threaten all three girls, and they start to wonder: will they ever see one another again?

Release date: June 9, 2010

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 300

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Twopenny Rainbows

Anna Jacobs

Ismay Michaels saw one or two bystanders step towards them uncertainly and if there hadn’t been a priest involved, she thought they might have helped her – but there was, so no one actually did anything.

Panting, the men shoved the girls into a compartment.

‘This defiance will do you no good,’ Father Cornelius warned.

As the train pulled away Ismay straightened her clothes and helped her sister Mara do the same, then sat as far away from their parish priest and his helper as she could. ‘You’ve no right to do this! No right at all. We could manage on our own.’

The priest sighed and repeated, ‘You’re only just turned fifteen and your sister’s eleven. There’s no way you could earn a living and make a home for yourselves now your parents are dead. You know there isn’t.’

‘Keara promised she’d come back here to Ireland and we’d all live together.’

‘Well, your sister is needed in England to help her mistress who’s expecting a baby, so she can’t do that now and—’

‘I’ll never forgive her for abandoning us, never!’ Ismay put her arm round Mara’s shoulders. ‘Neither of us will.’

‘Keara’s doing what she thinks is best for you. Why, Mr Mullane himself has arranged for the good Sisters of St Martha and St Zita to take you to Australia. You’ll be able to make far better lives for yourselves there than you could if you stayed in the village.’

‘I don’t believe you. And anyway, we don’t want to leave Ireland.’

When they got off the train, Ismay fought again, on principle, but once the big door of the convent thudded shut behind her she stopped struggling because what was the point? She became aware of Mara’s trembling hand clutching hers and her little sister’s tear-stained face, so put an arm round her. She didn’t dare give way to tears, had to be strong now, so focused on her anger as she stared at the inside of the convent. Everything here was made of stone – big, square stones that seemed to press down on you – and the chill of the place made her shiver. Or perhaps it was fear of what was going to become of them now.

Two brisk young nuns in long black habits and white wimples came into the parlour.

‘These men have kidnapped us!’ Ismay announced at once.

After a startled look at the priest, the taller nun said quietly, ‘Thank you, Father. We’ll see to them now.’ When the two men had left, she said, ‘I’m Sister Catherine and I’ll be going to Australia with you. If you’ll come to the kitchen we’ll find you something to eat. Everyone else is in bed, but we waited up for you.’

They trailed after her, Ismay still with one arm round her little sister’s shoulders. When the nun set some cake in front of them, Mara whispered, ‘Will we eat it, Ismay?’

‘I suppose so.’ After finishing the cake and drinking a big glass of milk each, they followed the nuns to a long, narrow room whose walls were lined with shelves bearing piles of neatly folded clothes.

‘Now, what size are you?’ the tall one wondered, shaking out a skirt. ‘I think this one will fit you, Ismay. Just try it on for me, will you?’

The girl shook her head. ‘We don’t want your horrid old clothes. We just want to go home.’

The nun’s voice became steely. ‘Either we do it by force or you take those clothes off this minute and try the skirt on.’

For a moment Ismay stared at them defiantly, then her shoulders drooped and she blinked furiously. ‘I’ve got something in my eye,’ she muttered as she saw Sister Catherine looking at her in concern. Taking off her clothes as slowly as she could, she tried on the ones she was given, then took them off again and donned the plain white cotton nightdress the nun handed her. She managed to hide the fact that she was amazed at having brand new clothes, or a long dress just for sleeping in. The shoes amazed her as well – two pairs each, plus a pair of slippers. What did you need two pairs of shoes for? You only had one pair of feet!

Sister Catherine and the other nun picked out a whole pile of clothes in their sizes. ‘Right then. You two carry the shoes and we’ll take you to your bedroom.’

The room was very simply furnished and immaculately clean. Even the wood of the bedheads was polished. Ismay studied the two narrow beds and so far forgot herself as to go and finger the soft blankets and sheets. There were also two chairs, a small washstand with ewer and bowl, and two clean, neatly folded towels. The beds were high enough to show the plain white chamber pot underneath one, and at the foot of each stood a sturdy metal trunk, lid gaping open.

The nuns placed most of the clothes in the trunks, leaving out skirts, blouses and sets of underclothes for the next day.

Finally Sister Catherine stepped back and nodded in satisfaction. ‘There, that’s everything you’ll need for your journey. You may as well go to bed now. The others went to sleep a while ago.’

‘Others?’ Ismay asked.

‘The other orphans. We’re taking a group of ten girls out to Australia.’ She hesitated then said quietly, ‘It won’t be so bad, you know. You’ll be well looked after.’

‘They shouldn’t be sending us to Australia at all! We have a sister in England working for the Mullanes and we should be going to her.’

‘She must have given her permission or you wouldn’t be here.’ Because Sister Catherine could see how very unhappy they were, she added, ‘None of us has a choice about going to Australia.’ At their looks of surprise she added with a slight smile, ‘I don’t particularly want to leave Ireland, either, you know.’

The other nun cleared her throat and gave her companion a disapproving glance, so Catherine cut short what she was about to say and finished, ‘Sleep well, girls.’

The two women left as quietly as they seemed to do everything else, taking the candle and locking the door behind them.

Ismay immediately got out of bed and sat very upright on the edge, swinging one leg. Mara hesitated but lay where she was, pulling the blanket up with a tired sigh. ‘Shall we not go to sleep now?’

‘Not yet, no.’ When her eyes had adjusted Ismay found the moonlight bright enough for her to investigate the rest of the contents of the trunks. Underneath the clothes were all sorts of things: a prayer book, sewing materials, writing implements.

It was as she started to put the things back that the idea occurred to her. ‘I’ll show them what I think of their horrid clothes!’ she muttered and took the scissors from the sewing kit. The idea was so monstrous that she hesitated for a moment, then with a toss of her head began to cut up their new clothes.

‘Ismay! Ismay, what are you doing? Don’t!’ Mara whispered, horrified.

‘Why not? Look what they’re doing to us. You go to sleep. This’ll take me a while.’

It took her a couple of hours to do the job properly, by which time her fingers were blistered. Once her little sister fell asleep she didn’t even try to hold back her tears and the resultant pile of rags was well watered.

In the morning they were woken by bells. A short time later Sister Catherine came in, mouth open to say something, but stopped short and stared at the pile of shredded cloth beside each trunk, her expression changing to one of shock, then horror. ‘What have you done, child?’

‘No worse than you’ve done to us,’ Ismay repeated, expecting a slap. She was puzzled when the nun looked at her instead with compassion written clearly on her face.

‘I’ll have to tell Reverend Mother about this and she’ll be furious. Oh, Ismay, can you not accept what’s to happen to you?’

‘No, I can’t and I never will!’

An older nun was brought to see what the new girl had done and stood for a moment looking at the pile of ragged pieces of cloth and muttering under her breath a prayer for patience. Her voice grated with the effort it took her to say, calmly and evenly, ‘If you do that again, Ismay Michaels, I’ll separate the pair of you. Permanently. Send one to Australia and leave the other here.’

Mara gave a wail and flung her arms round her sister.

Ismay stared back at the grim-faced nun. ‘You’ve no right to do this.’

‘We have every right. You should be grateful that your landlord has paid for you to go to Australia. You’ll have a far better chance of a decent life out there. They’re crying out for decent young women as maids and wives.’

‘Well, we’re not—’

The old nun raised one finger in warning. ‘Quiet! Just remember what I said if you want to stay together!’

If they separated her from Mara, Ismay didn’t know what she’d do. She bit back an angry sob, looking at the hard, unyielding face that was not at all like Sister Catherine’s whose expression was kindly. ‘I hate you!’ she flung at the Mother Superior.

More clothes were found. When they were alone again, locked in the room even in the daytime, Ismay and her sister sat on one of the beds cuddled up close.

Mara made a sad sound in her throat and wiped away a tear with a corner of the new white pinafore. ‘Do you think maybe Keara doesn’t know about this?’

‘Of course she does. How can she not be knowing? Didn’t they send a letter to Father Cornelius to say she wanted us to go? She couldn’t even be bothered to tell us herself or –’ her voice faltered for a moment as she fought to control it ‘– come to Ballymullen to say goodbye. As far as I’m concerned, she’s no sister of ours and I hope I never see her again as long as I live. If I ever do, I’ll spit in her face, so I will.’

Mara continued to sob quietly.

A few tears escaped Ismay’s control but she made no attempt to wipe them away, just hugged her sister close. She was the elder and she had to look after Mara now. If anything happened to separate them, she was sure she’d die of grief.

Malachi Firth crept into the house. He’d hoped his family would all be asleep by now, but there was a lamp still burning in the kitchen. Outside, the small Pennine village was blanketed in mist so thick he’d had trouble finding his way home, even the couple of hundred yards from the alehouse. Damned mist and rain! That’s all they’d seen for weeks. Lancashire must be the rainiest place on earth. Sometimes he longed for a sunny day.

As he closed the back door he saw his father rise up from the far end of the scrubbed wooden table, scowling at him as usual, and Malachi’s heart sank.

‘You’ve been with those louts again! What do you mean by staying out till this hour when you’ve a long day’s work ahead of you tomorrow?’

Malachi scowled right back. He wasn’t drunk or even tiddly, couldn’t afford it on the meagre wages his father paid him. ‘They’re good lads and I only had a glass or two of ale! Where’s the harm in that?’

‘They’re ne’er-do-wells and you shouldn’t hang around with folk like them. Your brother shows a deal more sense in the friends he makes, and our Lemuel doesn’t waste his time at a common alehouse, either.’

That was because Lemuel’s wife hardly let him breathe without permission, but Malachi knew better than to criticise her to his father since she’d recently borne a son to carry on the family name. ‘I do my work here and I’m entitled to a bit of fun in my spare time.’ Besides, it’d been a singing evening tonight and Malachi, who had a good baritone voice, dearly loved a sing-song. He’d won five shillings for being the best singer, by popular acclaim, but his father thought singing in public below the dignity of a Firth and a master cooper’s son. Malachi winced as the deep voice roared out its scorn.

‘Fun! What’s fun got to do with it when you’ve a trade to learn? You’d be better saving your pennies than wasting them on ale. How will you be able to set up your own cooperage when your time comes if you don’t save your pennies – aye, and your farthings too?’ He gestured round him. ‘This place must pass to the eldest son and don’t think I’ll split it between you.’

Suddenly the thoughts Malachi had been holding back for a while burst out. ‘Coopering’s a dying trade, Dad, and we all know it, even if you won’t admit it!’

‘Folk will always want barrels and buckets making.’

‘I don’t see any point in slaving through an apprenticeship when there’s not enough work to go round.’ Malachi never normally voiced his thoughts, but he agreed with those who said a galvanised bucket was better than a wooden one, and lighter too. Even before the Cotton Famine had impoverished so many in Lancashire, coopering had been losing custom to factory-made goods. But he didn’t want to start that old argument again.

His father made angry noises in his throat at this rank heresy.

Fed up of the continual carping, Malachi turned to go up to his bedroom, then swung round in shock as a thud behind him shook the wooden floor. John Firth lay spread-eagled on the rag rug, motionless apart from one twitching foot. Alarmed, Malachi yelled for his mother to come quick.

But there was nothing she could do – or the doctor when he eventually came.

His father lay unmoving in his bed for two long days and nights, then died abruptly of another seizure.

Afterwards Malachi’s elder brother cornered him in the kitchen. ‘I hope you can live with yourself!’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You drove Father to an early grave, worriting him with your boozing and not buckling down to learn the trade like you should have done. I’m telling you straight: I shan’t be taking over your apprenticeship, you ungrateful pup! You can move out of here and find yourself another job – if you can. I don’t even care what becomes of you.’

Defiance made Malachi shout, ‘I was leaving anyway. Think I’d want to work with you!’ He glared across at the brother who was both taller and stronger than he was and who had never scrupled to use his strength to get his own way. Lemuel took after their father’s side, tall men with rock-hard muscles, while Malachi took after their mother, thin and dark-haired, full of nervous energy, with a mind that wouldn’t be still but must always wonder at the world around him.

She came quietly into the kitchen to say reproachfully, ‘Shame on you both to quarrel like this with your father lying unburied above you!’

Lemuel folded his arms and scowled. ‘I meant what I said, Mam. He’s not staying here when me and Patty move in and I’m not continuing with his apprenticeship.’

She looked from one to the other and sighed. ‘No. It wouldn’t work, not with you two so different.’ They’d always quarrelled, right from the time they were little lads, to her great sorrow. ‘But I’d be grateful if you’d keep the peace until after the funeral, then we’ll decide together as a family what Malachi should do.’ Her glance held both young men captive as she added loudly and clearly, ‘And there will be no throwing him out of this house, Lemuel, because if you do, you throw me out as well. Your brother has as much right to a decent start in life as you do and this is his home, too.’

Lemuel shuffled his feet, then shrugged acceptance of her edict.

That evening Malachi managed to snatch an hour with his mother after Lemuel and Patty had gone home. Everything was ready for the funeral. And afterwards – well, everything would change.

‘I’m worried about you,’ he said abruptly.

‘About me? Why?’

‘Because of how Father left everything. He ought to have left you a share.’

‘He trusted Lemuel to look after me.’

‘Lemuel, maybe, but not that spiteful bitch he’s married to.’

Hannah Firth sighed. ‘There was no changing your father. He was set in his ways when I wed him. He’d never leave the business or house to a woman.’

‘Why did you mar—’ He broke off, knowing he had no right to ask this question, especially now, when it seemed doubly disloyal to that still figure lying upstairs.

Hannah sighed. ‘I had my reasons. It wasn’t a love match, but he was good to me in his own way.’

‘What shall you do now? You’ll never be happy with Patty in charge here.’

His mother gave him a sad smile. ‘What choice do I have?’

‘You’re young enough to do something else. Why, you’ve hardly any grey in your hair, even, and you’re still as active as a young woman. You could even marry again.’

She put one finger on his lips. ‘Shh. Now isn’t the time to discuss that sort of thing.’

But Malachi lay awake and worried about her. His sister-in-law Patty was already giving herself airs and looking round the house with a proprietorial air. Lemuel wouldn’t stand up to her. He didn’t dare breathe without his wife’s permission.

The following day, after the funeral guests had left, Patty sat feeding her baby son in the kitchen while Hannah Firth led her sons back into the front parlour. ‘Time to talk,’ she said briskly, holding her own sadness at bay. ‘Have you had any thoughts about what you want to do, Malachi?’

He hesitated, knowing it would hurt her, then said in a rush, ‘Emigrate to Australia.’ He looked out of the window at the rain that had fallen steadily all day. ‘I’m sick of grey skies and damp air. They say it’s sunny all the time in Australia.’

Lemuel let out a scornful snort. ‘Nowhere’s sunny all the time, you fool! And what are you going to do in Australia that you can’t do here?’

‘I don’t know yet. Sell things, perhaps.’ Dealing with customers, even if it was only a young couple buying a bucket, was the only side of the cooperage that Malachi enjoyed and he was good at it, too. He looked at his mother, pleading silently for her understanding. ‘I’ve been thinking about going for a while, but I thought I might as well finish my apprenticeship first. Now . . .’ He shrugged. He watched her nod, could see the sadness in her eyes, but could do nothing to help her.

‘I know you’ve been restless, son. But you’ll do this properly, so until we have it all worked out, you’re staying here. I’m not sending you out into the world penniless, not if I have to sell my wedding ring to fund you.’ She looked at Lemuel as she said that and he shuffled his feet and avoided her eyes.

Patty came to the door of the parlour, rocking her baby in her arms and scowling at them. ‘I don’t think that’s fair, Mother Firth. Your husband left the business to Lemuel, not Malachi. He has no right to any of the money.’

‘What do you think about that, Lemuel? Is it fair that he gets nothing, not even a start in life?’ Hannah stared at her elder son, knowing that although he was under his wife’s thumb and had been even before they married a year ago, he was an honest soul, as like his father as any son could be. At twenty-two he was already set in his ways while Patty, three years younger, bade fair to become a shrew. Hannah was dreading living with them, absolutely dreading it. But she wouldn’t burden Malachi with that. He, at least, should go free.

Lemuel looked from one to the other, then muttered, ‘I’ll give him a bit of a start, but I’m not depriving my child of his inheritance. If Dad had wanted Malachi to have owt, he’d have left him summat more than his watch.’

Hannah didn’t say that there hadn’t been as much to leave as John had hoped, for the coopering trade had been going downhill even before these difficult times. She watched Patty toss her head and storm back to the kitchen. ‘Tomorrow we’ll start planning,’ she told her sons, then went through into the kitchen to help her daughter-in-law clear up, biting her tongue when sharp orders were rapped out as if she didn’t know how to run her own home. Patty was taking charge even before she moved in.

Not until Hannah was alone in bed that night, her last in the big front bedroom, did she give way to her grief – and if she was crying for the loss of her younger son, not her husband, no one else would know that from looking at her reddened eyes.

Tomorrow, when Lemuel and Patty moved into the house, she’d be taking the small room at the back of the kitchen where her own mother had ended her days. She wasn’t looking forward to living in another woman’s house, but that’s what happened when your man died and there wasn’t enough money to give you a separate home.

Almost she wished she could go out to Australia with Malachi. She was only forty-two, after all, not old in looks or ways. But she didn’t dare suggest going because she knew Lemuel would kick up a fuss and refuse to give them any money for fares if she tried. For her younger son’s sake, she must just accept her new role in life and be grateful she still had a roof over her head.

But it was going to be hard living with Patty. One of the hardest things she’d ever done.

A few days later the nuns took the orphans to the docks and escorted them to the steamer which took them all across to Liverpool where they stayed in another convent. The porter from their own convent went with them to help keep an eye on the two rebels.

Ismay felt no excitement at her first sight of England, just dismay that they had found no opportunity to escape. They were closer to Keara than they’d ever be again, and here she was, helpless to find her older sister.

As they crossed the dock a few days later towards the much larger ship which would take them to Australia, the stern-faced nun who would be the Mother Superior in charge of the convent in Australia from now on held Mara’s arm tightly, and the porter from the Irish convent held Ismay’s arm even more firmly.

Sister Catherine, following with the rest of the orphans, felt her heart go out to the two Michaels sisters. Most of the other girls being sent out to Australia under the nuns’ migration scheme were pleased to be going. She sent up a brief prayer that the two rebels would find happiness in their new life, then turned her thoughts firmly back to getting the other girls settled in their tiny four-berth cabins while the older nun and the Matron in charge of the single women’s quarters made sure the Michaels sisters were safely locked up.

Not until the ship was under way were Ismay and Mara let out of the tiny cabin at the end of a row which the two nuns would occupy from then on because it was one of the few with a proper door, not a blanket hung across the entrance.

On deck the two girls joined the other orphans, all easily recognisable by their dark clothing. A few were weeping as the ship moved slowly away from land. Sister Catherine moved among them offering quiet words of comfort, but like theirs her own eyes kept going back to the horizon.

Ismay stood with Mara by the rail and watched England fade into a misty outline, seeing nothing but a blur of colours through her unshed tears. Anger hummed within her and it helped her find the courage to continue looking after Mara and make the best of their present circumstances. At least she had one sister still. That was the most important thing.

Suddenly the clouds parted and shafts of sunlight shone down through them. There was an ‘Oooh’ from the passengers as a rainbow arched across the sky, perfect in every shimmering detail.

Mara stared up at it, entranced.

‘A rainbow for hope,’ Ismay said quickly. ‘It’s a sign, that’s what it is.’

‘Do you really think so?’

‘I’m sure of it, yes.’

‘Remember how Mam used to ask us to take her back a pennyworth of sunshine when we went to the shop?’ Mara said wistfully.

‘That rainbow’s worth more than a penny,’ Ismay declared. ‘It’s a twopenny rainbow, that one is. Ah, Mara darlin’, we’ll be all right, I’m sure we will. And every time we see a rainbow, we’ll remember Mam, eh?’

Mara smiled and leaned her head against her sister’s shoulder, comforted, but Ismay’s expression was bleak and the colours of the rainbow ran one into the other as tears threatened again. She had to summon up more anger to keep them at bay and even then she was sure Sister Catherine knew how close she’d been to sobbing aloud.

*

Malachi continued to work with his brother so that no one could say he wasn’t earning his keep, but the atmosphere in the house was full of tension.

Most of all he resented the way Patty treated his mother, who had until this time been mistress here but who was now ordered around and treated as a servant by her sharp-tongued daughter-in-law, and a rather stupid servant at that.

‘Why do you put up with it, Mam?’ he asked.

His mother shrugged. ‘What else can I do, love? When your husband dies, you’re dependent on your children.’

‘Maybe you should come with me to Australia, then? I’d never treat you like that.’

‘Don’t be silly. I’m far too old for that sort of thing. And I have my own room here, with my favourite bits and pieces. That’s a great comfort to me.’

He spent part of the last evening with his friends at the alehouse, to Lemuel’s loudly expressed disgust. What did his brother’s feelings matter, though? After tomorrow morning he’d not see Lemuel again, not miss him either.

At the alehouse people popped in all night long to wish Malachi well. An hour after his arrival, his closest friends began nudging one another and John Dean disappeared into the back room.

While he was gone the others sat Malachi on a chair and with much laughter blindfolded him. He sat straining his ears, wondering what they were planning, and heard a murmur which heralded the return of John.

‘Hold thy arms out, lad,’ his friend’s deep voice said in front of him. ‘We’ve got summat for thee, summat to remember us by.’

Resigned to them playing some sort of joke on him, Malachi did as they asked and found himself holding something quite large. When they whipped off the blindfold, he stared down at what was surely – it couldn’t be, but yes, it was – a guitar in a sturdy canvas case.

‘My uncle’s had this in his attic for years,’ John said, grinning. ‘So we bought it off him as a going-away present.’

Malachi couldn’t speak for a moment. John of all people had known how he’d longed for a musical instrument of his own, any instrument would have done. But of course his father wouldn’t have one in the house. ‘Eh, lads.’ His voice was so husky with emotion he had to pause for a moment and swallow hard, then managed only, ‘I don’t know how to thank you enough.’

He undid the buckles holding the case shut and pulled out the guitar. Someone had polished it – he could smell the beeswax.

‘My uncle fitted new strings,’ John said. ‘And we bought you some spares.’

Gently, Malachi ran his fingers across them. The notes came out sweet and soft.

‘There’s this, too.’ John thrust a small book at him. ‘It tells you how to play it.’

Malachi bowed his head and said hoarsely, ‘Eh, lads, I’m going to miss you all that much!’

‘Don’t go, then!’ someone shouted. ‘Who’ll sing to us now?’

He raised his head, aware that they must be able to see the tears in his eyes. Well, to hell with that! ‘I shall think of you every time I play this.’

He didn’t stay much longer, wanting to spend a quiet hour with his mother.

Patty and Lemuel continued to sit up until well past their usual bedtime, with Patty making snippy little remarks about how she hoped he wouldn’t be sorry about what he was doing – when he knew perfectly well she hoped he would fail in Australia.

In the end, Hannah said quietly, ‘If you two want to stay up late tonight, Malachi and I can go into my room to chat.’

‘I suppose we’re not good enough to sit with you!’ Patty snapped.

Lemuel shushed her and gave her a push in the direction of the stairs. As he turned to his brother, he hesitated then said, ‘I wish you well, though I doubt you’ll succeed out there. You’re not steady enough to settle to any sort of work. But it’ll be no use coming back to me for help. I must put my own family first.’ After a brief hesitation he held out one hand.

Malachi breathed deeply, annoyed at his brother’s words, but shook the hand and contented himself with saying, ‘One day I’ll make you eat those words.’

Lemuel turned to his mother. ‘You allus did favour our Malachi, but I hope you’ll remember from now on that I’m the man of the house and it’s me who’ll be looking after you, not him!’

When he’d gone upstairs after his wife, Malachi held out his arms to her. ‘Come and give us a cuddle, Mam. A good big one. It’ll have to last a long time.’ He could feel her shaking with the effort of holding back her tears. Well, he felt like weeping like a babby himself, he did an’ all.

They didn’t even try to go to bed, neither wanting to waste a minute on sleep. Sometimes they talked, sometimes they sat quietly. Hannah held his hand most of the time and once she dozed for a while, her head on his shoulder.

He looked down at her dark hair, surprised to see how few grey threads there were in it. He was glad she looked younger than her age; young enough to remarry, he hoped, and escape from Patty. He blinked furiously. Hell, he hadn’t thought it would hurt this much to leave her.

In the morning, when he heard his brother stirring upstairs, Malachi shook her awake and said urgently, ‘I just wanted to say, Mam, that if you ever want to come out and join me in Australia, you’ll be welcome. I’d walk through fire for you and don’t you ever

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...