- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

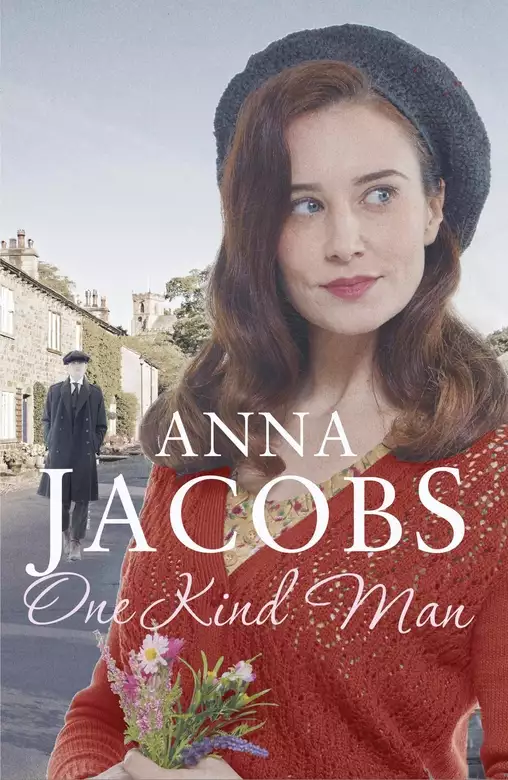

Synopsis

From the beloved and bestselling Anna Jacobs' comes the second novel in her new Lancashire-based saga.

1931, Lancashire:

When Finn Carlisle loses his wife and unborn child, he spends a few years travelling to keep the sad memories at bay. Just as he's ready to settle down again, his great-uncle dies and leaves everything to him. This includes Heythorpe House in Ellindale just down the road from Leah Willcox and her little fizzy drink factory.

Finn finds a village of people in dire need of jobs, a house that hasn't been cleaned or lived in for thirty years and Reggie, an eleven-year-old who's run away from the nearby orphanage and its brutal Director Buddle. When Finn sees the marks left by regular beatings, he decides Reggie will never go back there.

He can't turn away two hungry young women from the village seeking jobs as maids, either, and they too need help with their lives.

But Buddle has other plans for the child, and will stop at nothing to get Reggie back in his cruel grasp. His new neighbours help him save Reggie but other surprises throw his new plans into turmoil.

Release date: January 11, 2018

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

One Kind Man

Anna Jacobs

I hope you enjoy my new series, set further up an imaginary Pennine valley from Rivenshaw in a tiny village I’ve called Ellindale. The stories are set during the early 1930s. How I enjoyed researching that era in more detail!

If you’re interested in what England was really like in the 1930s, try reading J. B. Priestley’s English Journey. He went round England and wrote about what he saw in a most entertaining manner, thus providing me with a great research resource. Thank you, Mr Priestley!

One of the things that inspired me to write historical novels in the first place was the sense of history I grew up with. There were a lot of older people in our family, since one grandma was one of twelve children, her husband one of seven and the other grandmother one of four. The tales they used to tell fascinated me. The final grandfather would never talk about his family and I don’t remember meeting any of them. You have to wonder why!

I’m fortunate enough now to be custodian of the family photos and I knew most of the people in them, even though I might not have known them when they were young. I love to look at them, and study not only the costumes but the expressions on their faces.

I shan’t share the photo of my great-grandfather with you (1860s) as he’s one of the scariest looking men I’ve ever seen with a great big dark beard. He has such a fierce expression that as a child I didn’t like the photo.

Later I found out that in those days you had to stay perfectly still for over a minute to be photographed. Hard to do that and keep a pleasant expression on your face. Just try to smile happily at a camera for a minute and a half without moving and you’ll see what I mean!

You might like to meet my great aunt and great-grandmother, though. The photo with the long dress and towering hairdo from the early 1900s is my Great Auntie Peg – my father’s favourite aunt on his mother’s side. She didn’t have any children, but she was happily married and she certainly led an interesting and fashionable life. She remained lively right till she died in her early 80s. In her 70s she dyed her hair bright red for a couple of years for the fun of it. It looked awful, but she didn’t care. She’d look at herself in the mirror and fall about laughing.

In great contrast is my great-grandmother, Ann Wild, my maternal grandfather’s mother. He was one of her seven children. She was a quiet, gentle woman, rather like the heroine of the first Ellindale story. I still have her blouse from the late 19th century and it’s incredibly intricate. No one would have the time to make such an elaborate blouse these days. It’s one of my treasures.

I hope you enjoyed these tastes of ‘real history’ as well as my historical fiction that’s based on such research. I’ll end this letter by wishing you a happy visit to Ellindale. My great-grandmother and other Gibson ancestors are buried in a very similar village called Cross Stones near Todmorden. The little cemetery (not used now) lies above the village on the very edge of a windswept moor. It’s a fascinating place to visit.

The characters in this story are as near to the Lancashire people in my family as I could manage in the way they face the ups and downs of life, and look after their family members. I hope you enjoy meeting them.

Lancashire: 1931

Alexander Finlay Carlisle, more often known as Finn these days, picked up the letter that had taken a while to catch up with him and cursed under his breath when he saw the address embossed on the back of the envelope. It showed a firm of lawyers, the ones who usually handled his family’s affairs, the few there were these days because he came from the poorer side.

He wasn’t sure he wanted to read it because there was only one close family member left who might want to contact him and he didn’t want to deal with his cousin. He turned the envelope round and round in his fingers, looking at Sergeant Deemer, who had passed the letter on to him. ‘I could wish you’d thrown this in the fire. Couldn’t we … lose it?’

‘I’m afraid not, Finn lad. The District Inspector forwarded it and asked me to make personally sure you received it. Took me a while to find you, though. What were you doing in Edinburgh of all places?’

‘I was doing a small job for someone, finding a lost daughter.’ Finn sighed as he looked at the letter again. He’d tried to leave his past behind him, and had managed to do that for a few years, but it seemed to be catching up with him again.

The only way to have completely avoided this would have been to emigrate, he supposed, but he could never have done that. He’d been born in Lancashire and kept wanting to come back here, even now. It was home: grey skies and rain, soft sweet drinking water, wind across the moors, drystone walls, small mill towns clinging to the sides of valleys and, above all, friendly people who weren’t as afraid to chat to their so-called betters as some rather meeker folk he’d met on his travels in other parts of the country.

‘Oh, well.’ Taking a deep breath, he slit the envelope neatly along the top with his penknife. He didn’t like doing things in messy, clumsy ways, but his fancy paperknife was stored in a friend’s barn with the rest of the possessions from his previous life. He was only just beginning to think of retrieving them.

He folded the blade of the penknife back into its case, looking at it with fond approval. He’d used that clever little knife for many purposes while he tramped the roads of England, trying to walk himself into a new life but gradually realising that he’d been running away from the place where his sadness might heal more easily.

He’d stopped running now, so he’d better stop fiddling around and damned well deal with this letter. He pulled it out of the envelope. It was typed on the very best notepaper, which felt silky smooth beneath his fingertips and crackled faintly when he spread it out. It was dated nearly three months ago.

Linton and Galliford

Drake Street

Rochdale

20th May, 1931

Dear Mr Carlisle,

We regret to inform you that your great-uncle, Oscar Dearden, has passed away. He appointed us as his lawyers and executors of his will many years ago.

It’s my pleasure to tell you that he has left all he owned to you, which includes a property near Rivenshaw. You are the only nephew he recognises, since he disowned his half-sister’s son, Digby Mersham, many years ago.

We have had some difficulty finding you, and I’m afraid the death occurred some months ago, on the 10th of August last year to be precise, with the funeral two weeks later.

You were sighted in Rivenshaw recently and Inspector Utting informs us that you have been returning to the area intermittently to assist your former colleagues in the police force, so we have some hope that this letter will reach you sooner or later.

We respectfully request that you come to see us at our rooms in Rochdale at your earliest convenience. We will then give you full details of the bequest, arrange the transfer of all necessary goods and chattels, and hand over the smaller items, including keys, that were in your uncle’s possession when he died.

Yours faithfully,

George Linton,

Senior Partner

Finn reread the letter, but it gave no details of what exactly had been left to him. He vaguely remembered meeting his father’s elderly uncle a couple of times when he was a youngster, and remembered that Oscar Dearden owned a house somewhere on the edge of the moors, but had no idea why the man would leave anything to him.

And fancy Uncle Oscar living near Rivenshaw, of all places! Finn had spent a few weeks there earlier in the year, doing a job for the local police force. It was a nice little town at the lower end of a long, narrow Pennine valley.

He turned to his companion. ‘Do you know somewhere called Heythorpe House, Sergeant Deemer? It’s supposed to be near Rivenshaw.’

‘The name seems familiar, but I can’t quite place it. I mustn’t have had anything to do with its owner because once I’ve visited a place, I never forget it. It’ll be out in the country somewhere.’

It was good that this hadn’t happened until now, Finn thought. He was ready to settle down again, though he didn’t intend to marry – not again, never ever again! But if his great-uncle had left him a little money, it’d come in handy in the peaceful life he was planning to lead.

There couldn’t be very much involved in this bequest or his former father-in-law would have known about it. The man had been very skilled at sniffing out money and had been furious at his daughter for marrying a mere policeman who brought very little of it into the family.

But Ivy hadn’t cared for that. She had fallen in love with Finn as quickly as he had with her.

Deemer cleared his throat and Finn looked up, swallowing the hard lump that came into his throat sometimes still when he thought of his late wife. ‘Sorry. I was daydreaming. It seems I’ve been left a small inheritance.’

At his sigh, Deemer raised one eyebrow in the way he had when questioning something. ‘That’s good news, surely?’

‘I suppose so. It’s taken me by surprise. I’d forgotten my father’s Uncle Oscar, because he was a recluse and I hadn’t seen or heard about him since I was a child.’

‘Well, it’s good timing if you’ve just finished a job. This will give you something to move on to, lad.’

He liked the way Deemer called him ‘lad’ and acted half the time as if he was an honorary uncle. It was Deemer who had first offered him one of the little jobs that had helped him start to put a decent life together again and stop wandering aimlessly.

He studied the letterhead. ‘I’d better go to the Post Office and telephone these lawyers, hadn’t I?’

‘Use the phone here. Inspector Utting can’t object, because he was the one who forwarded the letter and asked me to deal with it.’

Finn took a deep breath and made the phone call. The clerk he spoke to said Mr Linton was with a client, but gave him an appointment for the following morning.

Well, he could wait another day to find out what his great-uncle had left him. He was tired after travelling back from Edinburgh and would go to bed early.

The following day, Finn made the journey by train, annoyed that he had to go into Manchester and out again to get there, since there was no direct branch line connecting Rivenshaw to Rochdale. Well, this was a small town and Rochdale was much larger.

It would have been much easier to get there by motor car. Once he had a job, he intended to save up and buy himself one, a second-hand Austin Swallow or something like that. Maybe, if he was lucky, his uncle would have left him enough to buy some modest vehicle.

Grey skies made Rochdale look bleak and it was chilly for August, so Finn walked briskly down towards the town centre from the station to warm himself up. It was easy to find the lawyers’ rooms because Drake Street was on his way.

George Linton was grey-haired and plump. He greeted Finn briskly and wasted little time in civilities, so Finn decided it must be a small, unimportant bequest.

‘Your uncle has left you a house,’ the lawyer began.

Finn stared at him in shock. ‘A house? What sort of house?’

‘Quite a large one, but it’s been neglected for a good many years because he inherited it from an elderly cousin and never lived there. It’s near Rivenshaw, as I said in my letter, but in fact he preferred to stay in his comfortable lodgings in Rochdale. He enjoyed reading, so visited the library frequently, and went to the theatre both in Rochdale and Manchester.’

‘Was he married?’

‘No. He preferred to remain a bachelor and indeed, his landlady told my clerk he never had a visitor in all the years he was with her. A very solitary type of gentleman, your late uncle.’

‘Where exactly is the house? The police sergeant in Rivenshaw who passed on your letter hadn’t heard of it.’

‘It’s not in Rivenshaw but near it. If I understand correctly, there’s a long valley with the town at the lowest point, a large village called Birch End part way up the slope and a small village called Ellindale at the upper end, just about on the moors. Your house is in Ellindale and I gather there’s only one other house further up the valley.’

‘Good heavens! I spent some time in the district earlier this year, so I’ve already seen the house, though only in the distance as it’s half-hidden from the road.’

‘Well, that makes my job easier. I won’t need to explain anything else about the location to you.’

Finn tried to pull himself together. The last thing he’d expected was to inherit a house, and for it to be in Ellindale made him feel good because he liked the village and its people. It was a rather special place.

‘He has left you some money as well. It’s invested and brings in enough to live on if you’re careful.’

‘Money too!’ Finn shook his head, finding all this unreal, as if he was in a dream. ‘I didn’t know my great-uncle was well off.’

‘In a modest way. You mustn’t think you’ve inherited a large fortune.’

‘I didn’t expect to inherit anything. Is that all?’

‘There are the contents of the house, of course. It’s apparently fully furnished still, because when your great-uncle inherited it, he simply locked the house up and walked away. He told me it could stay like that for all he cared, because he preferred to live in the lodgings where he was so comfortable. I believe he had some maintenance work done occasionally on the house to keep it weatherproof, but never went there himself.’

‘Good heavens! My father said his Uncle Oscar was a strange fellow and always had been. It was known in the family that even as a child, he preferred to be on his own and hated to have his daily routines disturbed. They were relieved that his strangeness wasn’t, um, troublesome to other people.’

‘That fits with what his landlady told my clerk when he went to collect your uncle’s personal belongings. An ideal tenant, she called him, no trouble, never made a noise.’

The lawyer pushed a leather satchel across his desk. ‘These are the contents of his pockets and of the desk in his lodgings. We took it upon ourselves to return some library books, but there are quite a few other books and papers, which we have stored here in our cellar. We can send them on to you once you’ve settled in.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Do you have any questions?’

‘No. Do you think there’s anything else I need to know?’

Mr Linton steepled his hands together, wrinkling his brow. ‘I can think of nothing else. We only saw your great-uncle twice, once when he came to make his will and once when he came to sign it and make a statutory declaration that nothing was to go to his other great-nephew. If you had died or weren’t found after five years of searching, everything was to go to a children’s charity of some sort.’

He pushed a folder of papers towards Finn. ‘This contains a copy of the will and a list of what’s in the satchel. If you wish to check it before you sign for it, my clerk will find you some desk space in the outer office.’ He looked across at the elegant gilt clock on his mantelpiece. ‘Unfortunately I have another appointment shortly.’

‘No need to check it, I’m sure. Where do I sign?’ He didn’t really care what was in the satchel, after all.

‘Here. Thank you.’

Finn scrawled his signature with the expensive modern fountain pen that was handed to him. He might buy himself one of those. It wrote beautifully.

‘There’s one more thing we need to do: get your uncle’s bank account transferred to you. My chief clerk will take you to the bank now, if you like. It’s not far from here.’

As he walked out, Finn felt literally heavier, as if he had entered the lawyer’s rooms a free spirit and come out loaded with possessions and responsibilities. Which was foolish, really. Because he’d also come out with enough money to live on and a home to live in. It was very timely. Perhaps he felt strange because he wasn’t used to being lucky.

But what sort of home would it be if it hadn’t been lived in for years? From the way people in Ellindale had talked, the house was in a tumbledown state.

And how would he spend his time if he settled in a small village? The only thing he was certain of was that he didn’t want to go back into the police force, even though he’d enjoyed helping out with one or two small jobs.

In fact, he had no idea what to do with the rest of his life, only that he wanted it to be worthwhile.

And he wasn’t going to marry again. No one could replace Ivy.

The farm cart creaked its way slowly up the hill from Rivenshaw and the old man driving it glanced back over his shoulder to see whether the lass was still breathing. She’d been so weak when they laid her in his cart, poor thing, that he’d wondered how long she’d survive.

Yes, she was breathing. She was a fighter, Lily Pendle was. He’d known her since she was a little lass and she hadn’t had an easy life.

When he got to the village of Ellindale he breathed a sigh of relief. No need to ask the way to the shop run by Nancy Buckley. It was such a small village there was only one shop and one pub too. He’d have a wet of ale at The Shepherd’s Rest before he started back, while his old mare Betty had a good feed and a drink from the horse trough outside the pub.

He drew up just as a woman was about to go into the shop, so he left the reins lying. His horse was old, like him, and tired. She wouldn’t budge for a good while. ‘Excuse me, missus. Is this Mrs Buckley’s shop? Good. Could you please ask her to come out and help me? Only I’ve brought her cousin’s lass, who’s sick, and I can’t carry Lily in on my own.’

The woman nodded and went quickly inside.

‘Nancy, there’s an old man outside with a sick young woman on his cart and he says she’s your cousin’s lass.’

‘What?’

Nancy was out from behind the counter in a flash, running out of the door.

The customer put her basket down, wedged the doorstop in place and went to see if she could help.

‘Ah, there you are, Nancy. You never change,’ the old man said. ‘I’ve brought your cousin Roland’s lass. Lily needs looking after. Her mother just died and the poor girl is as weak as a kitten.’

‘Is it something catching? Only I’ve a shop to run.’

‘No. The two of them have been trying to manage with nowt to eat but the odd piece of bread. What the government is doing letting decent people starve to death, I don’t understand. Mean, that is. Does it think folk don’t want to find work? They’re as hungry for work as for food, poor souls, but there isn’t much of either around these days.’

Nancy was already clambering up on to the back of the cart. ‘She has a look of my cousin. Not many people have such silvery-blond hair.’ She stroked it back gently. ‘Well, let’s get her inside.’

‘You’ll have to help me. I’m getting a bit old for carrying folk. Only no one else had the time to drive her all this way. I reckoned if she was left without help for another day or two, we’d have been too late to save her. You have to tend someone who’s this weak, build up their strength again. So me and my old mare brought her to you.’

The customer joined them. ‘Let me help carry her, Mr …?’ She looked at him enquiringly.

‘Trutton. Sidney Trutton.’

The woman turned to the shopkeeper. ‘Why don’t you go and get ready for her, Nancy? Mr Trutton and I will carry her in.’

‘Thanks, Leah. Don’t try to take her upstairs. She’ll have to lie on my couch, so that I can nip in and out of the shop to serve my customers as well as keep an eye on her.’

It wasn’t until the young woman had been taken through to the back room that Nancy thought to ask, ‘How did you come to be helping her, Mr Trutton?’

‘I’m a neighbour of theirs in Martons End. It’s only a little village so you won’t know it but it’s near Netherholme on the other side of Rivenshaw.’

‘I do remember Martons End slightly, but I was only a child when I went there.’

‘Well, then. You know how small the place is. Even I didn’t know how bad things were for them. Mrs Pendle allus kept herself to herself after her husband went, you see. Our farm is outside the village. The farm belongs to my grandson now, because my son died at Ypres and I can’t manage the heavy work, not at my age.’

‘I’m grateful to you, Mr Trutton. Very grateful indeed. Did Lily’s mother really die of starvation?’

‘Yes, missus.’

‘I’d have taken them food myself if I’d known.’

‘So would other folk. But Mrs Pendle were too proud to ask for help, an’ she starved her poor daughter along with herself. By the time Lily defied her and came to us for help, her mother were nobbut a skeleton and she died quick as that.’

He snapped his fingers to illustrate the point, then went on, ‘False pride, I call that. As if folk wouldn’t have spared the odd crust. Look how you’re taking this lass in without hesitating.’

‘These are hard times,’ Nancy said with a sigh. ‘I haven’t seen my cousin for years. Roland should have come to me for help if he needed it. I suppose he died first. When was that?’

The old man sighed. ‘He didn’t die. Runned off, he did, a few years ago now, with a woman from the village.’

‘Roland did? Good heavens. I’d never have thought it of him.’

‘Well, his missus were a hard woman to live with, I’ll grant him that, though you shouldn’t speak ill of the dead. But he give her his promise in church and should have kept it.’

‘Who was the woman he ran off with?’

‘A neighbour. She left three little kids behind. Shame on the pair of them, I say. Selfish to the core. I heard tell they were going to Australia, but no one ever found out whether they got there or not. Lily had a live-in job as a maid when her father ran off and could send most of her wages home to her ma, but the family she worked for lost their money earlier this year and had to sack all their servants.’

He sighed. ‘Mrs Pendle wasn’t well by then an’ she needed someone to look after her, so Lily came home. A nice lass, she is, pretty too when she has a bit of flesh on her bones.’

He lingered for a cup of tea and it was a while before Leah could get him on his way. He was still talking as he climbed up on to the cart.

‘My grandson says he’ll clear the house and put their things in our barn. Plenty of room there. Though there’s not a lot left because they had to sell stuff to live.’

‘That’s very kind of you.’

‘Don’t lose my address now.’

‘No, I won’t.’

‘Give the lass my best wishes.’

‘I will.’ Smiling, Leah watched him go. He’d probably be talking to himself all the way back to his family farm. Ah! Now, he’d stopped at The Shepherd’s Rest. Well, who could blame him?

Nice old man, but did he ever stop talking?

She turned to Nancy. ‘I hope Lily gets better soon. Now, I need to finish my shopping and get home. I haven’t seen my little sister for ages, not to chat to. If I’m not busy, she’s up in her room studying.’

‘Your Rosa’s a nice lass, quiet like you, but pleasant to everyone. You’re doing a good job of mothering her.’

‘I hope so. I’ve been looking after her since our mother died. Goodness, that was over eight years ago now. She’s growing up so quickly.’

Lily Pendle opened her eyes and stared round, not recognising the room or the woman hovering nearby. ‘Where am I? Who are you?’

‘I’m your cousin Nancy and this is my house. Mr Trutton brought you to me in his cart. You were unconscious when we carried you in.’

It took a few moments for the words to make sense, then Lily studied the woman. ‘Are you really our Cousin Nancy? My father used to talk about you. You visited one another’s families sometimes when you were children.’

‘We did. We’ll talk about our families later, though. I think the main thing is to get some food into you. Do you think you could start with a drink of milk?’

Lily could feel herself blushing in embarrassment at being so needy. She couldn’t even take the glass herself because she was too weak to hold it safely.

‘Let me help you with that, dear. Just sip the milk slowly. How long since you’ve eaten?’

‘Two days, I think. Or was it three?’

‘And before that?’

‘I don’t remember. We haven’t been eating properly for a while. There was no money after I lost my job, you see, and my mother wouldn’t accept charity. She was so fierce about it, so sure we could manage till I got another job. But how could I leave her? She was weaker than she would admit.’

She added bitterly, ‘When my employer went bankrupt, he couldn’t even give us servants the wages we were owed and you can’t eat a character reference, can you? That was so unfair of him because he paid all the tradesmen. Why couldn’t he have shared the money out among everyone he owed?’

She sipped again. ‘My mother was so stubborn. There were no more small items left to sell or pawn, you see, and she had no way of taking the bigger pieces of furniture to the pawnshop without people seeing what was happening – as if they didn’t know! – so she refused to do it.’

‘Of all the stupid, false pride!’ Nancy exclaimed involuntarily.

‘I agree. I was going to have it out with her, only I found her dead in her bed that very morning. They took her body away and gave her a pauper’s funeral. She’d have hated that but I didn’t have any way of paying for a proper funeral.’

She paused, gathering the strength to finish her tale. ‘I got soaked at her funeral and then had to walk two miles home. I fell ill and I don’t remember much after that.’ She paused again, weak from the effort of talking. ‘I was feverish and calling out, I think. Someone must have heard me.’

The glass was empty now and her kind cousin patted her hand a couple of times as if offering comfort. And it was comforting.

A bell clanged and Lily turned her head slightly. ‘What’s that?’

‘This is a shop and that’s the doorbell. I have to go and serve a customer. I’ll be back soon. It’s not a busy time, so we can get you settled and find something for you to eat in a while. Why don’t you have a little doze?’

She bustled out and Lily closed her eyes. There was the sound of voices in the next room, but she couldn’t be bothered to listen. She was so very weary.

Her cousin was lovely, so kind.

Maybe I’m not going to die after all, she thought as she snuggled down.

When Nancy had finished serving two customers and went into the back room again, she found her young cousin sleeping, a little frown creasing Lily’s forehead.

Roland Pendle, what were you thinking of to run away and leave them? She stared down at the gaunt young face and lank hair, with just a few short wisps showing its true colour. It sounded as if her cousin’s wife died of starvation, and this poor girl might follow her mother if she couldn’t regain her strength.

‘Well, she’s not going to die if I can help it,’ Nancy muttered aloud.

What that lass needed to build up her strength was a good hearty broth. You couldn’t beat it. She’d have to send down to Birch End for some stock bones and stewing beef, but there were always people around to run errands for a penny or two. She’d had the telephone put in, but telephones couldn’t carry shopping back, could they?

She went and looked out of the shop door for someone just as Tom Dotton was slouching past. He hadn’t had a job for a year or two, poor man, and had trouble filling the empty hours each day.

‘Like to earn threepence?’ she asked.

He brightened up immediately. ‘You know I would, Nancy. Any time.’

‘I’ll pay you to walk into Birch End and get me something from the butcher’s.’

It cheered her up to see how he straightened his shoulders at the prospect of earning even such a small amount.

‘Come in and I’ll get my purse. A shilling’s worth of good beef stock bones is what I want, and half a pound of stewing beef. Here.’ She took out a few broken biscuit pieces. ‘To help you on your way.’

He sighed at needing her handout but took the biscuits. ‘I’ll pay you back one day for helping me, Nancy. Even a few pence can make a big difference to feeding the kids.’

‘Get on with you. You’re running an errand for me. That’s not charity, but you doing a job in return for payment. My niece has just arrived to stay and she’s been ill. She needs feeding up and the sooner the better, so come back as quickly as you can.’

She watched him take a bite of a biscuit as he set off down the hill and wished she could do more for him. But she didn’t have much money to spare herself. If it hadn’t been for the hikers who bought refreshments from her shop on fine weekends, she’d not have had any pennies to spare to pay people to run errands. Or to get the telephone put in. She was still unsure whether that was too extravagant, but she could always have it taken out again.

Eh, the folk in her village were having a hard time of it, they were that, and it was the same all over Lancashire, if the tales in the newspaper. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...