- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

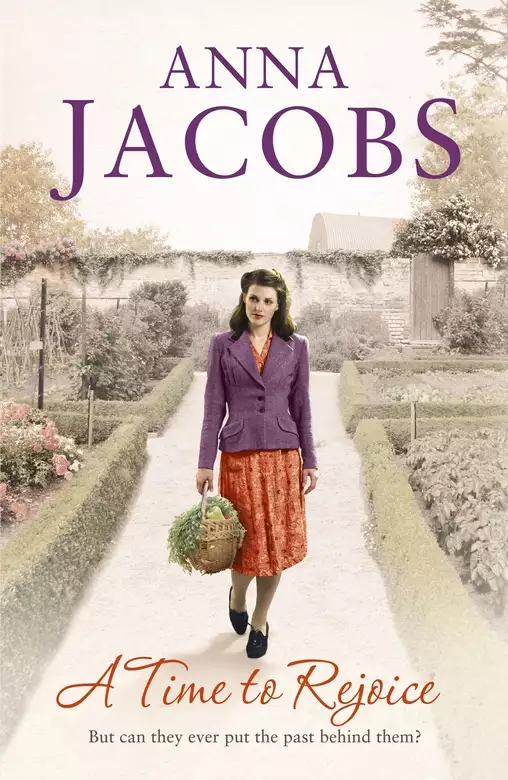

The heartwarming third instalment of the Rivenshaw series from bestselling saga writer Anna Jacobs.

After a stray bomb scored a direct hit on his childhood home in Hertfordshire, the only thing that has kept Francis Brady going while he works day and night salvaging what he can from the rubble is the thought that soon he'll be joining war-time friends Mayne, Daniel and Victor as electrician in their new dream building firm in Lancashire.

But things are not going to plan: Mayne isn't answering any of his letters; Francis' wife is having a change of heart about moving up north – and her parents seem set on destroying his reputation... A lot of marriages are breaking up in these times of change, and Francis is loathe for his to be one of them... But how can he turn down the opportunity of a new life and career in Rivenshaw?

Meanwhile in Rivenshaw itself, newly married Mayne and Judith's plans to convert Esherwood house into flats have come to an abrupt halt. While clearing out the house in readiness for the rebuild, they've discovered that someone has been stealing valuables and hiding them in the old Nissen hut. But who hid them there – and are they planning on returning for them? And are they also responsible for something else found in the shelter: a body, buried in a shallow grave...

With so much going against them, can these four friends ever turn their dreams into reality?

(P) 2019 Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Release date: May 19, 2016

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 284

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Time to Rejoice

Anna Jacobs

He watched her pick her way across the rubble where his family’s garage and house had once stood. A stray bomb had scored a direct hit last year, the only one to land in the village, probably being dumped as the plane flew back to Germany. The bomb had destroyed everything and killed his parents instantly.

Diana scowled at him and his heart sank. She couldn’t have come because she’d changed her mind about helping him, then.

He waited for her to speak and when she didn’t, he tried to coax her. ‘If you’d just pick up these bricks as I dig them out of the rubble and stack them over there, I could finish work more quickly, then we could—’

She set her hands on her hips. ‘Why do you insist on doing this, Francis? You’ve been slaving away for days now, coming home filthy, with your hands all rough. And for what? To make a few measly shillings.’

‘Pounds, not shillings, and I’ve made far more than I’d expected, actually. Why do you ask when you know perfectly well why I want to make the extra money?’

‘But there’s no point to it! I met my father as I came through the village and he said again that you could sell this plot of land as it is. You aren’t going to build anything on it, after all, so there’s no need for you to clear the rubble. You’ve had a good offer already and my father says you can easily push the price up a bit.’

‘I’ll sell the land when I’m good and ready, and I’ll get a much higher price for it than has been offered by your father’s friend. But first I’m going to finish salvaging anything that’s sellable. Whole bricks make nearly as much money as new ones since the war ended, because of the scarcity of building materials, and so do pieces of decent milled timber, even the short ones that have had one end blown off.’

She let out an exaggerated sigh. ‘It’s not worth the extra trouble and even if it was, I don’t intend to ruin my hands by working like a navvy.’

He looked at her without a word. Two years previously he had fallen in love with Diana on sight and she with him. They’d got married after a few weeks, like many other couples in the war years, but he hadn’t realised how hard she’d be to live with, how much time and money it took to maintain her immaculate appearance … or how unused she was to hard work. No, he definitely hadn’t expected that.

He tried to speak patiently, though he was only repeating what he’d already said a dozen times. ‘It is worth the trouble, Diana. You have to make the most of every single penny when you’re starting up a new business.’

‘You aren’t a businessman! You’re a mechanic. You’d be taking a huge risk and you might lose everything.’

There she went again, being scornful about his background. This usually happened after she’d been with her damned father. ‘Being a mechanic doesn’t mean I’m stupid, Diana.’

‘Then be sensible. My father knows someone who’ll give you a job, with the chance to become chief mechanic when the old one retires. That way you won’t have to work such long hours. And once you’ve sold your parents’ land, we’ll have enough money to buy a decent house without borrowing anything.’

He looked at her in shock. ‘We’ve already got a nice house.’

She went pink. ‘Ah. Well. I didn’t make a fuss because of the war, but our present house is rather small and … well, ordinary. I couldn’t think of starting a family till we’ve got somewhere better to live and bring up our children.’

Francis could hear his own voice grow suddenly harsher and didn’t care. ‘How many times do I have to tell you that I don’t want to work for anyone else, especially one of your father’s friends. That man treats his staff badly, which is why he has trouble keeping anyone for long.’

He looked round with pride at what he’d accomplished. ‘I’m getting to the end of the salvage work now. Come on, Diana. Lend me a hand. You don’t need to damage your hands. I’ve got some working gloves you can put on.’

She took a step backwards, shaking her head vigorously. ‘No! I wasn’t brought up to do rough work and if you cared about me, you wouldn’t even ask. Besides, it looks like rain.’

He looked up at the sky. ‘Maybe a light shower. A bit of rain won’t hurt you.’

‘It’ll make a mess of my hair. I said no and I meant it. Oh, there’s no talking sense to you!’ She stormed off down the street.

He saw the envelope sticking out of her coat pocket and yelled after her, ‘Don’t forget to post my letter!’ She’d walked right past the post box on the way here. Why hadn’t she popped the letter in then?

She didn’t answer, but he saw her finger the corner of the envelope, so he knew she’d heard him.

Feeling depressed about their quarrels, which seemed to be getting steadily worse, he continued to sort through the rubble. Thieves had stolen the first pile of bricks he’d retrieved, so he slept here in his car whenever the builder couldn’t collect the day’s piles of salvage at teatime.

Diana hated him doing that, too. But he had to protect his property because there were looters everywhere since the war.

It disgusted him. He’d put his life on the line to defend his country and now the war was over, some people were ready to steal from him. Well, he wasn’t going to let thieves make off with the fruits of his hard work. The building company he and his friends were going to set up in Rivenshaw was his big chance to make something of himself. He needed money to invest in it, wanted to be a partner, not an employee.

He took a breather and glanced round, remembering what it had once looked like, with the garage right next to the house and the vegetable garden on the other side. He’d grown up here, enjoying a very happy childhood. He’d only known Diana by sight in those days, because she came from the posh side of the village and went away to boarding school for most of the year.

When his parents were first married, they’d started up a bicycle repair business in a wooden shed and had sold petrol in big square cans. Each can had held two gallons, if he remembered correctly. Too heavy for a little boy to lift when he desperately wanted to help, but they’d found him other jobs and he’d been proud to do them well. He had never stood by and watched others work.

His parents had saved their money and bought this piece of land when he was about ten. He remembered them standing hugging one another next to the tumbledown old cottage, their eyes full of dreams.

After that, his father had started repairing motor cars as well as bicycles. They’d installed one of the new petrol pumps, too, instead of selling cans of petrol. And they’d all lived in the cottage, happy to be together, doing the place up bit by bit. He doubted his mother had ever worried about breaking her nails.

Francis had picked up a lot of his father’s mechanical skills even before he was old enough to do an apprenticeship with a qualified motor mechanic. He’d intended to go into the family business and had planned to sell cars later on. Ordinary cars for ordinary families.

Then the war had intervened and he’d been called up. He’d managed to get posted to work on maintaining equipment and had joined the Royal Corps of Electrical and Mechanical Engineers after it was formed in October 1942. He’d learned so much about modern electrical equipment in the army.

He was down to the foundation of what had been his home now. Tears welled in his eyes and he brushed them away with his sleeve. His parents should be here with him, enjoying the fruits of their hard work. He still missed them, turned round to ask his dad something or saw a woman selling flowers in the street and thought of buying a bunch for his mum.

He could never take money for granted, as Diana did. Her father was a solicitor like his father before him, so the Scammells were comfortably off. They hadn’t approved of their daughter’s marriage, even though Francis had been promoted to captain by that time.

Her father had even offered him money not to marry her, claiming they were too different to make a go of it, but Francis and Diana were both over twenty-one, so could do as they pleased. He’d never told her about that offer because she idolised her father. In the end, Mr Scammell had come round and insisted on arranging the wedding, so that it wouldn’t shame the family. What a waste of money that had been!

But perhaps Mr Scammell had been right, after all. Perhaps Francis and Diana weren’t suited.

One of the other chaps involved, Mayne Esher, owned a run-down old manor house and several acres of land in Rivenshaw, a small Lancashire town. The house had been requisitioned during the war, but had been returned to the family a month before the war in Europe ended. It was obvious by then that the Allies were going to win, so the government had started shedding its wartime acquisitions and gearing up for peace.

Sadly, Mayne didn’t have enough money to restore Esherwood and live there. Like many other places, it had been carelessly damaged by its wartime occupants. But it was large enough to be converted into several luxury flats, perhaps even as many as twelve, which could then be sold at a profit. After that, the Esher Building Company would build houses on the rest of the land and sell those.

Francis was getting rather worried, though, because he’d written to Mayne after VE Day and again after VJ Day, when the war finally ended in the Far East, and he hadn’t heard back. That puzzled him and he still didn’t know if they were on track to start their business.

No, of course the project would still be a goer. He’d trust these particular friends with his life.

He’d asked Diana to find out if the Eshers were on the phone, and she’d discovered that the Rivenshaw telephone exchange had been badly damaged by bombs and was still being repaired.

That wouldn’t have stopped Mayne getting in touch, so perhaps he had a family crisis or something had gone wrong at Esherwood. It wasn’t going to be easy for anyone, authorities or citizens, to adjust to peace.

If Francis hadn’t been so busy, he’d have nipped up to Lancashire to find out what was going on and why his letters hadn’t been answered. But if he left the block unattended, it’d be looted.

Perhaps their building company wouldn’t get off the ground. In that case Francis would start up in business for himself, though that’d have to be in a much smaller way. He was determined not to work for anyone else. He’d had enough of being ordered around during the war, thank you very much, more than enough.

Nor was he going to live near the Scammells. His marriage would have no chance with them interfering.

Besides, what Diana conveniently ignored in all this was the reason he’d managed to get demobbed early: the fact that he was going to work in the building industry. As long as he did that, he could stay out of the army. If he worked at any other job, they’d call him back to serve out the rest of his time till it was his turn to be demobbed, which was calculated by age and the months served in uniform.

Her father might be able to fix that, as Diana claimed, but Francis didn’t want to start his civilian life by cheating and he very much wanted to go into business with his friends to build decent homes for people.

More than two million homes had been destroyed in German air raids during the war, so the construction of new dwellings was one of the biggest priorities for the recently-elected Labour government, and rightly so, Francis felt.

He was lucky to have his own home. There was such a shortage of accommodation that people were squatting in abandoned government camps and buildings.

Mr Scammell regularly waxed eloquent about how shameful this squatting was, but didn’t have any suggestions to make about how people who’d fought for their country could find somewhere to live. It was all right for him in his big, comfortable house, but people were tired of squeezing into small houses belonging to relatives.

And of course, other homes and buildings had been damaged and would need repairing, some in a major way. Maybe he and his friends could pick up that sort of work, too. Scammell was wrong. There was a lot of money to be made in the building industry.

Just as important to Francis, it’d all be worthwhile. He’d be creating, not destroying.

He came out of his reverie as the builder turned up, earlier than expected, and they began to load his truck.

Once he’d been paid for today’s salvage, Francis decided to go home straight away and take Diana out to the cinema. Surely that’d cheer her up?

When he saw his mother-in-law’s small Austin Seven saloon parked outside his house, Francis slowed down with a sigh. Christine Scammell was always polite to him, he couldn’t fault her on her manners, but somehow he never felt quite at ease with her.

He opened the front door and went into the hall just as the two women started laughing. They didn’t hear him and he was about to call out, but heard his own name spoken and couldn’t resist listening.

‘Do you want your father to try yet again to talk sense into Francis, Diana dear?’

‘No, Mummy. It’d do no good. He’s got his mind absolutely set on us going up to live in Lancashire. I let him talk about it during the war, because it seemed to give him comfort, but I thought he’d see sense after he left the Army and got used to living in Medworth again.’

There was a silence, then, ‘You haven’t changed your mind, though. You don’t want to move, do you?’

‘Of course I don’t. You and Daddy are here. All my friends too. I’d know no one up there. Anyway, I don’t want to live in one of those ugly industrial towns. I’ve seen them on the Pathé News at the cinema – they’re all smoky and full of common people living in rows of nasty little terraced houses.’

‘We’ll have to think of some way to change your husband’s mind.’

‘I’m working on that, wearing him down gradually. You’ll see. I won’t let Francis do this to me. I just won’t.’

‘Good. Let me know if I can help in any way. I’d miss you terribly, darling. Your brother’s wife is so hostile to us, it’s as if we only have one child now. Have you heard from William lately?’

‘I’m afraid not.’

In the hall Francis gasped in shock. He knew very well that Diana had received a letter from her brother yesterday. She hadn’t shared its contents with him, except to say that William was fine. There must be something in the letter she couldn’t tell her mother about. What had shocked him most was how easily she’d lied to her.

Did she lie to him as easily? Surely not?

There was the sound of someone pushing a chair back and Mrs Scammell said, ‘Now, I really must go, Diana darling. I’ll see you tomorrow afternoon.’

Francis tiptoed into the kitchen and stayed out of sight until his mother-in-law had driven away.

When Diana brought the tray of tea things into the kitchen, she stopped dead at the sight of him. ‘I didn’t hear you come back.’

‘No. You and your darling Mummy were too busy trying to think of ways to stop me doing what I want with my life. Doing what we had planned till you suddenly changed your mind.’

She slammed the tray down on the table, setting the china tinkling. ‘Because it’s not what I want!’

‘No. You’ve made that plain enough. You won’t even give Rivenshaw a try. But it’s not you who has to earn the money, is it, Diana? Not you who’d have to work year after year in a job you disliked.’

He hesitated, then said it, because dammit, they were only going over the same old ground. And she had encouraged him while they were living away from her parents’ influence, had seemed nearly as excited as him about that sort of future.

‘We’re getting nowhere, Diana. I’m ready to sell this house now. When I do, perhaps you should go and live with your parents for a while and I’ll move up north on my own. You can take time then to decide whether you want to join me or not. It’s up to you.’

She looked shocked. ‘Francis, no!’

‘What alternative is there? I’ve got a wonderful chance to make something of myself and to make a far better future for us. I’m not going to turn it down.’

They stared at one another, then her expression hardened. ‘I thought we’d agreed to sell the house later, when you’re more sure of what you’re doing?’

‘No. We didn’t agree to anything. You decided that.’

‘Because it makes sense. You might need to come back here if things don’t work out in this Rivenshaw place.’

‘I definitely won’t be coming back to live in the village, whatever happens. I couldn’t find the sort of work I need here. I’m not just a motor mechanic now. I’ve learned so much more during the war. If our building company doesn’t eventuate, I’ll start up something of my own and for that, I’ll need to be in a town.’

‘Daddy says—’

‘Stop trotting out what your father says. It’s what you and I say that matters.’

‘I happen to agree with him.’

‘You always do. It’s about time you started thinking for yourself. And you might occasionally listen to what I tell you. I’ll say it one last time: if my friends and I start a building company, it will not fail. The four of us are like brothers, and our skills fit together perfectly for such work.’

‘Skills! What does a motor mechanic know about building houses or running businesses?’

He was shocked by the way she was sneering at him. He’d known her parents looked down on him for working with his hands, but she hadn’t seemed to feel like that when they married. She’d changed so much since she’d come back to live here during the past few months.

He shouldn’t have bought this damned house, but let her stay with her parents. Only, Mr Scammell had heard about the house and Francis had realised it would be an excellent investment.

Diana let out a huff of anger and began to put the cups on the draining board, rattling them about and making a lot of noise.

He reached out to stop her. ‘No, let’s finish this discussion once and for all.’

‘It’d be better to let our emotions cool down, Francis. We shouldn’t do anything till we can come to an agreement.’

‘I heard what you said to your mother. How many times do I have to tell you I won’t change my mind, whatever you say or do. As for this house, it’s gone up in value, so I’ll get a nice sum of money back, even after I’ve paid off the bank mortgage. I want as much money as I can scrape together to invest in Esher and Company.’

‘But this is my home too. And I don’t want to sell it.’

‘You just said the house is too small. How come you suddenly don’t want to sell it?’

‘It is too small, but I want to live near my parents.’ She burst into tears and dabbed delicately at her eyes.

She was waiting for him to put his arms round her, he knew, and he didn’t like to see her cry, so he usually stopped arguing at this stage. But too much was at stake: the rest of his working life. He had to make a stand.

He left her weeping and went into the hall to hang up his jacket. He couldn’t help noticing that the sobs stopped abruptly once he left the kitchen.

As he hooked his jacket into place, he saw the corner of his envelope still protruding from her coat pocket and called, ‘You didn’t post my letter.’

She came hurrying out to join him, looking guilty. ‘Sorry. I’ll just nip down to the post box now. I, um, have a letter of my own to send as well.’

‘I’ll come with you.’

‘No need. You’re tired and dirty. You need a bath and a change of clothes. You know I don’t like the neighbours seeing you looking like a working man.’

‘I am a working man, a very hard-working man.’

‘You know what I mean.’ She snatched her coat and backed away towards the front door, making a shooing motion with her hand. ‘Go up and get your bath.’

But she’d looked so guilty, he’d have known she was up to something, even without overhearing what she’d said to her mother. After a moment’s hesitation, he followed her down the street, taking care not to get too close. But she didn’t look back.

When she got to the post box, she stood staring at it, holding the letter in front of her in both hands.

What the hell was she waiting for?

She moved at last, but didn’t push the envelope into the slot. He watched in shock as she tore the letter up and shoved the pieces into a nearby dustbin. And she didn’t have a letter of her own to post, either.

He nipped round the corner and pressed closely against an overgrown hedge, mostly hidden by its foliage, waiting for her to pass.

A terrible suspicion was making him feel literally sick. She couldn’t have … No, surely not? But what if she had done this before? That would explain why he hadn’t heard from his friends.

Francis didn’t go straight home, couldn’t face Diana yet. He had to get his own anger under control first because you didn’t make good decisions when you were seething with rage.

He walked round the village for a while, trying in vain to calm down. In the end he went into the pub for half a pint of beer. He waved to some fellows he knew but didn’t join them, choosing instead to sit out in the garden on one of the rough wooden benches, even though the evening was rather chilly and the bench was damp from a recent shower.

After the years of blackout, it still felt strange to have lights on out of doors or to leave curtains open at windows after dark.

Everything in his life felt strange today.

He took a slurp of beer without really tasting it. Diana must not only have been throwing his letters away, but intercepting anything that came from Mayne and the others.

None of his friends would leave a letter from him unanswered and they had his address, so they’d be wondering what had happened to him. He thumped one fist on the rough wooden table. How could she do that to him? How could she?

After a while, he felt a few raindrops on his face and hands. Muttering in annoyance, he raised his glass to finish the beer, then realised it was already empty. Rain began falling steadily, so he stood up. Time to go home and confront Diana. That couldn’t be avoided any longer.

She was waiting for him in the front room, which she always called the sitting room.

He’d hardly hung up his coat on the hallstand when she started.

‘Where on earth did you go to, Francis? You knew I’d have your tea ready. And look at you. You’re wet through.’

‘That’s because it’s raining.’

‘I did notice that. But why have you been out in it? And you haven’t had your bath yet. Don’t sit down! You’ll dirty my upholstery.’

‘Our upholstery, surely?’ Annoyed by this barrage of sharp comments, he sat in the chair opposite her and spoke before she could say anything else. ‘I was having a think. I followed you to the post box, you see.’

Her mouth fell open and her expression suddenly became apprehensive. She looked like a schoolgirl now, not a married woman. She acted like one too quite often.

‘I saw you tear up my letter, Diana. Did you do that to the others I wrote to Mayne as well?’

She avoided his eyes, fiddling with the edge of a cushion.

‘Well? Aren’t you even going to answer me? Did you throw all my letters away?’

‘Yes, I did.’

‘And what about letters from my friends? Did they write to me?’

‘Yes.’

She had lost her schoolgirl air and suddenly looked so like her mother he was startled … and repelled.

‘We’ll talk about it later, Francis. The water’s hot for your bath, and you haven’t had your dinner.’

‘I’d rather talk about it now.’

She grasped the chair arms as if she needed to cling to something.

‘It’s against the law, you know.’

She looked at him in puzzlement. ‘What is?’

‘You can be prosecuted for tampering with the King’s post.’

‘Who’s going to know, so what does that matter?’

‘I know. Don’t I matter?’

‘Of course you do.’

‘How long did you think you could fool me for?’

‘Long enough for your friends to find another partner to replace you, I hoped. Or for you to see sense.’

‘You were very determined to stop me going to Lancashire, weren’t you?’

She shrugged.

‘Well, you’ve failed. I’m even more determined to go now.’

‘Please, Francis, don’t do that to me.’

‘It’s not just about you, Diana. I spent over a year planning the new business with my friends. You knew exactly what I intended to do because I talked to you about it whenever I came home on leave. Why didn’t you speak out then?’

‘I thought it was just … dreams. To get you through the war.’

‘Well, you’re right in one sense. Planning what we’d do when peace came did help get all four of us though the last year of the war. It was a beacon of hope. Because we were planning how best to kill people in that special unit. None of us enjoyed killing.’

‘You have to kill enemies.’

‘Enemy civilians as well? Women and children and old people?’

She shrugged.

‘We weren’t dreaming, we were finding something constructive to do with the rest of our lives.’

‘You can be constructive here, where we both grew up.’

‘No, I can’t. I want to build houses. I’m really keen to do that. I want to take care of the electrical side of things in our company. Electricity is going to become even more important as they start designing equipment for peacetime homes, which will have washing machines, refrigerators and who knows what else?’

As usual, she ignored what he was trying to tell her. ‘If you insist on moving to Rivenshaw, you can’t care about me. Did you ever really love me?’

He tried to say he had, but he couldn’t lie, because he was no longer sure whether it had been love or infatuation. The best he could manage was, ‘I thought I did at the time. And I believe it was the same for you. When you were called up for war work under the National Service Act, you’d never been away from home before. You were lonely. We both were.’

She nodded.

‘When we met at that dance, we recognised one another from the village, though we’d never actually spoken before. And for all our differences, we had some good times together.’

Her expression softened still further. ‘Yes, we did. You’re a wonderful dancer.’

Dancing. Parties. Social life. That was what she seemed to care about most. ‘Well, if it was love we felt, it wasn’t the sort to build our whole lives on, apparently, nor the sort where you work together to create a home and family.’

‘How can you say that? Of course it was love. It was! I’d not have defied my parents otherwise.’

He watched her put up one shaking hand to cover her mouth and allow tears to spill over it. He’d seen her do this a few times during the past two years. It was a very effective trick, making her look pitiful. Her father usually fell for it and gave her what she wanted, but she’d tried it on Francis one time too many.

‘That pretty little show of tears falling won’t convince me. Stop play acting and behave like a grown-up, for heaven’s sake.’ He wanted the full truth between them now and in the future.

If they had a future.

She let her hand drop, staring at him indignantly, the tears stopping immediately. ‘How dare you speak to me like that?’ She bounced to her feet.

‘Sit down!’ He hadn’t meant to use his parade ground voice, but it burst from him and she dropped back into her chair,. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...