- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

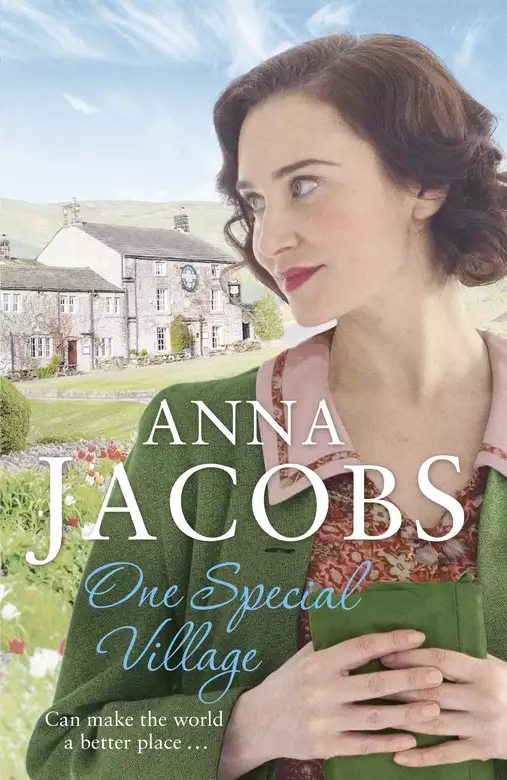

The third book in beloved and best-selling Anna Jacobs' Lancashire-based Ellindale saga.

Lancashire, 1932.

Widower Harry Makepeace lives in Manchester with his sickly daughter, Cathie, scrimping and saving to get by. But after she suffers a violent asthma attack, the doctors say she must move to the clean, fresh air of the countryside to have any hope of survival. When Harry chances upon a patch of land for sale in Ellindale and an advert for a disused railway carriage that can be made into a home, he snaps both up quickly.

Harry swiftly becomes part of the community in Ellindale, making friends with the locals, and soon finds himself attracted to Nina, another newcomer to the village. Finally, he's found somewhere he and Cathie can build a new home.

But their problems are far from over. Times are hard in Ellindale—Harry is not the only one struggling to find work. Then there's his old boss, who will stop at nothing to punish him for daring to leave. And Harry's already made an enemy in Ellindale—someone who could make his life very difficult indeed....

Release date: September 6, 2018

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 368

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

One Special Village

Anna Jacobs

As Harry Makepeace waited outside the Ward Sister’s office to speak to the doctor, he looked down the long children’s ward at the slight figure of his daughter, lying in a bed halfway along, and his heart twisted with pain.

She’d been taken bad at school and they’d had to call the ambulance to take her to the hospital. One of the older lads had been sent running to the factory to tell him, but by the time Harry got to the school, the ambulance had taken her away, and he had to catch two buses to follow it into Manchester. His employer would be furious about time lost.

If Cathie had been at home, he’d have tried the Potter’s powder, burning it and letting her inhale the smoke. It usually helped a little. But this remedy was working less and less well and he was at his wits’ end as to how best to help her.

The local doctor was an old man and he just shrugged when Harry took Cathie to see him. ‘We can’t perform miracles, Mr Makepeace. Don’t let her run around too much. Keep her calm. Some children get hysterical easily.’

Hysterical! This wasn’t hysteria; it was an illness.

When Harry asked him for the name of a doctor who specialised in treating asthma, the local doctor took umbrage. ‘Do you think I don’t know my job! Not one really understands asthma and many think it psychosomatic, which is what I just said, a hysterical reaction. It’s better if parents of such children treat them more strictly.’

Which was ridiculous. As if Cathie did it on purpose.

She’d never needed to go to hospital before or he would have tried to do something about it. He was going to find another doctor for her from now on, he decided.

‘Mr Makepeace.’

He looked up as someone called his name and Sister beckoned him into her office. He stood in front of her desk, looking down at the two people seated behind it. There was another chair at the side of the room, but they didn’t ask him to sit down. He held back his anger at that rudeness, reminding himself that Cathie was what mattered.

‘Your daughter has had a severe asthma attack, Mr Makepeace,’ the doctor said slowly and loudly, as if he were speaking to an idiot.

‘If you don’t mind telling me something about asthma, doctor, I’d appreciate it. I need to know as much as possible so that I can help her.’

The doctor studied him and he looked steadily back. Unlike some people he wasn’t cowed by doctors. They were only human beings like him.

‘Well, some people are starting to wonder if asthma is a disease of the lungs but no one’s sure. Personally I’ve noticed it’s worse where the air is impure.’ The doctor looked down at the admission form and tapped it with his forefinger. ‘Where you live is in the middle of an industrial area, is it not, and no doubt very smoky?’

‘Yes. But I need to live near the place where I work. I’m an electrical engineer. I keep the machines in a factory running.’ He always called himself an engineer, as they had done in the army where he’d been trained during the final two years of the war.

‘Indeed. But that isn’t a good place to bring up a sickly child, with the mills and factories belching out black smoke every day. The air there is dirty and when it’s breathed into the lungs, it dirties them in turn. This may be making matters worse in your daughter’s case. When I visit patients near mills, even I feel stifled sometimes and there is nothing wrong with my lungs.’

‘I see.’

‘Fortunately we were able to treat her with ephedrine and give her oxygen to breathe. Your own doctor will be able to prescribe it for you.’

‘He hasn’t done so far. He says the attacks are due to hysteria.’

‘Ah. Old gentleman, is he?’

‘Yes.’

‘Perhaps a younger doctor might be of more assistance?’

Although the sister was clearly impatient for him to leave, the doctor took the opportunity to stretch his arms and ease his shoulders, which gave Harry time to take this in.

‘Maybe cleaner air would help, doctor. Cathie wasn’t as bad when we used to send her to visit her grandmother in the summer, only the old lady died and I don’t know anyone else who lives in the country.’ He shook his head sadly. ‘Eh, what must I do?’

‘Get her out of the city to live in the fresh air of the countryside, even if you have to send her away to do it. It’s her only hope. If we hadn’t given her oxygen today she might not have pulled through.’

Harry could only stare at him in dismay.

‘She isn’t a strong child, as you must realise. Motherless too, I gather. How are you coping?’

‘We have a neighbour who helps. She’s kind, like an auntie to my Cathie.’

‘The child was clean enough when brought in,’ the sister said, as if reluctant to admit Cathie was well cared for. ‘Given what doctor says, and your lack of suitably placed relatives, it might be better for you to put her in the care of an orphanage in the country, Mr Makepeace. She’s old enough at nine to understand why and you could probably visit her occasionally.’

‘What? Nay, I’m not sending her away. She’s all I’ve got since her mother died and I love her dearly.’

‘There are other considerations as well as her health. Men aren’t the best people to bring up girls of her age anyway. She’s going to need a woman to show her how to deal with a woman’s body soon, not to mention teaching her how to look after a house when she marries.’

The doctor was scribbling on the admission form so Harry turned back to the sister. ‘Can I take Cathie home now?’

‘You’ll have to ask doctor.’

Harry had to wait for him to finish writing, scrawl his signature and look up. ‘It’d be better to leave her here till tomorrow. We have oxygen to hand if she has another asthma crisis.’

The sister stood up and gestured towards the door, her large starched headdress flapping up and down like a bird’s wings, and not a friendly bird, either, but one waiting to pounce on its prey. ‘That will be all for now, Mr Makepeace.’

The doctor was already reading the next paper from the pile and there were others queuing outside to see him.

Heartsick, Harry went down the ward to speak to his daughter, trying to hide from her how worried he was. Cathie seemed lethargic, her face pale, her thin body not making much of a lump under the bedclothes. This wasn’t like his lively little darling.

He wasn’t giving her away to an orphanage. Never! She coughed and he added mentally, well, only as a very last resort.

He sighed as the bell rang for the end of visiting hours, most of which he’d had to spend waiting outside the sister’s office. He bent to kiss Cathie. ‘I’m sorry to waste visiting time, love, but they insisted I had to see the doctor while he was here. I’m to come back for you tomorrow morning and take you home.’

Tears trembled on her eyelashes. ‘Oh, Dad, please take me home now. It’s horrid here.’

‘They say it’s best you stay in case you need oxygen again. Your breathing hasn’t settled down yet. Even I can hear the roughness.’

‘I hate it here. They care more about straightening the bedcovers than asking how you are. And you’ll lose another day’s work. Mr Trowton will be furious. I’m sorry, Dad.’

‘What are you sorry for? You didn’t do it on purpose. Just concentrate on getting better and leave me to deal with my boss. Getting better’s your main job now.’ He couldn’t resist giving her another kiss. ‘Be a good girl.’

Harry walked slowly out of the hospital, trying to get his mind round the new problem as he waited for the first of two buses home. If the doctor was right, something could be done to help Cathie. So he was going to do it, whatever it took.

There had to be a way to get her out into the country without putting her in an orphanage; there had to be.

He’d lost his wife to pneumonia two years ago. Dora had faded so quickly, he’d been left stunned by his loss, with a seven-year-old child crying for her mummy and depending on him for everything. That was when Mrs Pyne next door had stepped in for the first time, because Trowton had just sacked her on a whim, something he’d been doing more often lately. The woman was a saint.

Harry would give everything he owned, every drop of the blood in his veins, to make Cathie well again. But exactly how to do that was difficult to figure out. He had a job here and was lucky to have it when so many couldn’t find work, even though his employer was a mean old sod, and getting meaner with every year that passed. If he left Trowton’s, how would he live? He didn’t think he’d get sacked, though, because he was good at his job and there were a lot of old machines to keep going.

He arrived home to a silent house. It felt wrong to have no smiling daughter running to fling her arms round him. It was a two-up, two-down terraced dwelling near the factory, which was a smallish place, specialising in soft furnishings – curtains, cushions and all sorts of bits and pieces.

Mrs Pyne knocked on the door to enquire about Cathie, so he asked if she’d look after the child when he brought her back the next day, which of course she was happy to do.

‘You’re a wonderful neighbour, you are,’ he told her.

‘Get on with you! Let alone I’m fond of Cathie, it’s a poor sort who doesn’t help a neighbour.’

But he could see she was pleased with his compliment.

When he went back inside, he stood in the kitchen feeling numb, not knowing what to do with himself.

He’d intended to make do with a couple of slices of bread and jam for tea, but his stomach rumbled and he told himself he needed to keep up his strength. He nipped along to the corner shop for one slice of ham and a couple of carrots. He didn’t bother to cook the carrots, just washed them and crunched away between bites of ham sandwich.

He looked at the second carrot before he put it in his mouth and grimaced. Even the food was poor stuff if you lived in a place like this. When his father was alive, they’d had fresh vegetables all through summer and autumn from the old man’s big country garden, whatever was in season. He still missed that Sunday visit, coming back with shopping bags full of food.

Now they had to make do with what the local shops offered. Maybe good fresh food would help Cathie as well as fresh air. It wouldn’t hurt, that was sure. He’d have to make the effort to go to the market on Saturday afternoons to buy fresh stuff, though it meant a long walk.

He cleared up methodically after eating. His wife had been insistent on keeping a clean house and he’d seen how Dora did things, so he’d continued to tackle the various jobs the way she’d have wanted. He took care of most of the housework himself, with Cathie’s help now she was bigger, and to hell with the other men laughing at him and saying that was women’s work.

The only thing he couldn’t do himself was the washing – he just didn’t have the time – so Mrs Pyne did that every Monday with hers for a small payment, which she was glad to earn, and he also paid her a little something for keeping an eye on the child before and after school or during holidays.

They didn’t tell anyone about those payments, because Mr Pyne was on the dole and subject to the means test. If the authorities had found out, they’d have docked the money Harry gave her from her husband’s dole payment. Mean devils, they were, always suspicious! As if the poor chap was out of work on purpose and wouldn’t have preferred to go to a job.

He looked round the room and sighed. It was clean and tidy but that was all you could say about it. Dora had managed to make things look homely, but he didn’t seem to have the knack.

People kept urging him to marry again, but he didn’t intend to look for a wife simply because he needed someone to see to the house. Imagine living with a scold like Tom Blake’s wife, however cleanly her ways, or a poor housekeeper like Don Roason’s wife, who might have a lush body but was stupid and forgetful. Or, worst of all, someone who didn’t love Cathie. No, thanks.

He sat down and tried to read a newspaper he’d picked up on the bus. Fortunately someone had left it behind. But his thoughts wandered, because he was all churned up about what to do.

He ought to be able to find a job somewhere else because during the war, the army had trained him as an electrical engineer. He’d not had to do a lot of actual fighting, thank goodness, but had been kept busy in England maintaining equipment used on the home front. He’d been lucky, very lucky indeed. He hadn’t thought so at the time, though, as his friends had been posted all over the place and saw a bit of the world, while he was left in Aldershot, working his way through his training.

Harry smiled at the memories of Sergeant Deakins who’d been in charge of his group. He was strict but gave those in his unit the most thorough training in electrics you could possibly get. At the time Harry had fretted against the restrictions, because he’d only been a lad, hadn’t he, too stupid to know when he was well off? He’d lied about his age and enlisted at fifteen, so well grown that no one had questioned his age. He reckoned the sergeant had worked out that he was under age, though, and had kept him under his wing.

Even if Harry’s parents could have afforded to pay for an apprenticeship, they’d not have let him do one. They’d wanted him to work with his dad on the smallholding they’d rented for decades and had been sure the war would be over before he was old enough to be called up. They’d been furious when he ran off and enlisted.

He’d never gone back to live at home again. After he was demobbed he found a job in Manchester running in electricity to houses and lived in lodgings near his work. It wasn’t long before he met and married Dora. He’d actually been nineteen then, though folk thought him twenty-one, and she’d just turned eighteen. They’d been happy together and he still missed her.

It was a sorrow to them both that she’d only given him the one living child and had lost two others after Cathie. Neither of them had expected that because Dora seemed a fine, healthy lass in other ways. He’d have liked more kids but there you were.

When the doctor said another baby would probably kill Dora, Harry took care not to start any, even though preventive measures weren’t cheap at a shilling a protector.

But she’d died anyway, poor lass, and her only twenty-eight. Pneumonia was a scourge.

With Mrs Pyne to help look after Cathie, he’d stayed in the same house. Except that now he knew it was bad for his child’s health here, he would have to leave.

There had to be a way. He’d make a way.

And what was he doing sitting thinking about the past when it was time for bed? He’d have a busy day tomorrow.

Harry had to take part of the following morning off to pick up his daughter and Mr Trowton didn’t like it, threw a fit and said he’d fine Harry five shillings for the inconvenience, but there you were. She was too little and weak to travel home alone.

Then something distracted Trowton and he broke off in the middle of ranting about ungrateful employees who deserved fining. He was very strange at times as well as a bit forgetful. But with a bit of luck he might forget the fine. He’d sacked a woman last week, telling her to leave at the end of the day, then asked her to do a special job for him when she came to work the next day and hadn’t mentioned sacking her since. It was all very strange.

When Harry got to the hospital, Cathie was sitting on a hard chair near the entry to the ward waiting for him.

The sister came out of her office to see him.

‘Doctor says she’s doing all right but I’m to remind you she needs to get out of the smoky air.’ She thrust a piece of paper at him. ‘This is the address of a very good orphanage in the country.’

Cathie burst into tears.

He didn’t throw the paper back at the sister, which was his first instinct, because Cathie might wind up here again. He just muttered, ‘Thank you,’ then took his child’s hand and hurried away from the dratted woman.

Outside the hospital Cathie stopped to hold on to his arm. ‘She said you’d have to send me away to an orphanage in the country. Promise you won’t do that, Dad, promise.’

‘Of course I won’t send you away. I didn’t say anything in there because I didn’t want to upset Madam Starchy Knickers in case you had to come back here.’

The tears stopped at this rude nickname, and it won him a watery smile.

‘I couldn’t manage without you to boss me around, loviekins.’

As they found a double seat and sat down together on the bus, Cathie leaned her head against his shoulder and sighed, still clinging tightly to his hand.

Oh, how he loved the feel of that little hand in his! Yet how frail and weightless it seemed today. He didn’t think he could carry on if anything happened to her.

That settled it, time to use Dora’s money. When she died, he’d vowed never to touch the insurance payment, had considered it blood money, and put it straight into the savings bank.

Dora had taken the two policies out without consulting him, one on his life and one on hers, for the sake of their child. He’d considered it a waste of money and it had been one of the few things they’d argued about. He’d never expected to collect on a policy but she insisted on keeping up the payments, however much they had to scrimp.

But now, that damned blood money might be his only chance to help Cathie. He wasn’t sure how to do it yet, but he’d find a way.

Two days later, Harry was called in from the workshop by the owner. A stranger was standing by the office window, looking thoroughly fed up.

‘Ah, Makepeace. This is Mr Selby. He’s been looking at the old car that belonged to my brother, thinking of buying it. Only the engine won’t start. I had it working only last week, didn’t I, so there can’t be much wrong. Could you just have a look at it? You’re good with machinery.’

Harry didn’t contradict him, though this was a barefaced lie. The car in question, a Fairbie, hadn’t been used since the brother died.

‘Happy to, Mr Trowton. I’ll just go and get my toolkit.’

‘I’ll come with you,’ the stranger said. ‘I know quite a bit about cars, actually, but I don’t have any tools with me and I don’t want to get my good clothes dirty. I’ve never seen a car quite like that before.’

‘It was built a few years ago by a small company near here that’s gone out of business now, like a lot of them have,’ Harry said. ‘The car used to be a good runner. Not fast but steady and was known for its good brakes.’

Behind them, Trowton nodded approvingly at that remark.

Mr Selby followed Harry through the workshop and out to the long narrow yard at the side, where all sorts of bits and pieces were stored.

Someone had given the car a polish and tidy up, Harry noted. As if that’d make the engine run properly. ‘I’m not a car mechanic,’ he told Mr Selby, wanting to be fair to both parties, ‘I’m an electrical engineer. But I’m good with machinery and I do understand how car engines work, so I’ll be happy to have a go.’

They got the bonnet open and Harry shook his head as he looked inside. Trowton could at least have had the motor cleaned.

‘We can both see that the car hasn’t been used for a while,’ Selby said in a low voice, ‘but I guess you didn’t dare contradict your employer.’

‘In times like this a man has to hang on to a job.’

Selby walked round the vehicle. ‘I’d have left when it wouldn’t start, but the bodywork looked to be in good condition and strongly made. If I can buy it cheaply and get it to my workshop in Rivenshaw, I can pull the engine to pieces and get it working properly again. The parts don’t look too badly worn.’

‘I know Mr Trowton’s brother didn’t drive very far in it,’ Harry offered. ‘Now, let’s see what we can do.’

They chatted as Harry examined and fiddled with and cleaned the various parts of the engine.

‘What’s your job here, exactly?’ Mr Selby asked. ‘For a man who isn’t a motor mechanic, you seem to be making a good fist of checking it over.’

‘I like machinery, have a feel for it. My job is keeping the factory machinery running, mostly smaller stuff like sewing machines and electric irons, because the factory runs on electricity. This place used to be reasonably profitable, even during the war. But nobody’s thriving these days.’

‘You’re the head mechanic?’

Harry chuckled. ‘In practice yes, but not in name. That’d mean Mr Trowton having to pay me more. He calls himself the head mechanic.’

‘Places like this aren’t doing so badly in the south of England,’ the visitor said thoughtfully. ‘And the big factories producing motor cars, like Fords, employ hundreds. Only I wanted to live near the moors. The air’s bracing there, suits me better. I’m a northerner, heart and soul, I reckon.’

‘Where exactly do you live, if you don’t mind my asking?’

‘Rivenshaw. It’s in one of the Pennine valleys in Lancashire, near the border with Yorkshire. Good honest folk round there.’

Harry put that on his mental list of places to check out.

It took two hours of work to get the engine going, even with Mr Selby’s helpful suggestions. The owner came out twice to see how things were going, scowling at Harry as if it was his fault it was taking so long.

Then at last the engine coughed, as if protesting at being woken, and started chugging somewhat unevenly.

Mr Selby sat in the driving seat, touching the accelerator a couple of times when it faltered and listening as if he knew how engines should sound.

In the end he switched it off, poked his head out of the window and beckoned Harry over. ‘You did well. Want to earn a bit extra this weekend delivering it to Rivenshaw for me?’

‘I think you’d be better fetching a lorry and loading it on that, or towing it behind a bigger car. I doubt it’d get out to Rivenshaw under its own steam.’

‘If I came and towed it, would you sit in it and steer it for me? Driving under tow isn’t as easy as it looks. I have a partner in my used car business, but Charlie’s a terrible driver. I’d not trust him to do it.’

Harry thought quickly. ‘I work Saturday mornings so it’d have to be Sunday. And we’d need to start off early so that I’d be back before nightfall. I have an ailing child to look after, you see – and before you ask, my wife’s dead, so it’s all up to me. My neighbour would look after her in the daytime though. And I could maybe borrow a friend’s motorcycle to get back home and put it on the boot rack at the back of the Fairbie. I’m afraid I’d have to ask you to pay him five shillings to hire it. I haven’t got the money to spare. You know how bad the trains are on Sundays.’

‘You’re on. I’ll be over here by eight o’clock on Sunday morning. Do you want me to pick you up at home or meet you at the factory?’

‘Would it be too much trouble to pick me and the motorbike up from home?’

‘Not at all.’

‘Thanks.’ He gave Mr Selby his address and was thinking aloud when he added, ‘I’ll be able to look at the countryside as I go. The doctor says fresh, clean air is my daughter’s only chance. She gets dreadful asthma attacks, so I’ll have to find somewhere in the country to live.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that. Do you know where you want to go?’

‘Eh, no. Anywhere that will help my Cathie and provide me with a job will suit me. Last week she nearly died and was rushed to hospital. The doctor told me her only chance was to move to the country out of this smoky air. I’ve started looking in the paper for jobs and there doesn’t seem to be anything at all going out near the moors let alone in my line of trade—’

He realised he was talking too much. ‘Sorry. I shouldn’t bore you with my troubles. Please don’t tell Mr Trowton what I said. It’s just that my little lass is on my mind and it slipped out.’

‘Of course I won’t mention it. Good luck with your job hunting.’ Mr Selby slipped a ten-shilling note into Harry’s hand. ‘Thank you for your help today.’ He added two half crowns. ‘For the hire of the motorbike.’

Ten shillings was over-generous as a tip and Harry hesitated, hating to act like a beggar. Then he thanked Mr Selby and accepted it. He was going to need every penny to move and set up another house, and Mr Selby had a well-fed, healthy air that said he wasn’t scrimping a bare living, so could afford to tip well.

Harry still couldn’t think how to find a job, but this Sunday would give him a start on looking for a place to live. He was planning to visit the smaller nearby towns on Saturday afternoons or Sundays to see what he could find.

He put the old car away and watched Mr Selby make his way to the office to haggle with Trowton, then he went back to his own work.

At the end of the day, Mr Trowton saw the other workers off the premises and came to find Harry, who was making his final rounds to check that everything was switched off properly.

‘Well done, Makepeace. I sold the car to him.’

‘That’s good.’

He hesitated, then slipped two shillings into Harry’s hand. ‘You did well.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

His employer was a mean bugger, Harry thought as he walked home. Two shillings when he must have got at least twenty pounds for the car. Even a stranger had given a bigger tip than that. And Harry put a lot of extra time in here without complaining.

But at least Trowton’s factory was still doing business and though the number of workers had been cut drastically, there were still twenty women employed there, and three men for heavier work and deliveries, including Harry. The women cut, sewed and ironed, making up loose covers for furniture, curtains, cushion covers, antimacassars, whatever Trowton could find a market for.

They had other jobs to do for his cousin who had a similar place in the south, which was a big help. The other Mr Trowton had plenty of work, and could get some things made up in the north more cheaply than he could produce them himself without extending his factory.

Harry was still managing to keep the machinery going but some of it was getting very old and outdated. He worried about those machines. They all did. Who could afford replacements in times like these?

If the factory closed down before he’d found another job, what would he do?

When he got home, Harry knocked on Mrs Pyne’s door. He didn’t usually bother to pick up Cathie, just knocked and shouted that he was home. But today he needed to ask her about Sunday. She was happy to earn an extra shilling looking after the child, but his daughter cried when he said he’d have to leave her on the one day they usually spent together.

In fact, Cathie had been tearful and lethargic ever since she came home from the hospital. This made him even more certain he needed to get cracking and find a way to move. She might have recovered, but she wasn’t thriving.

In fact, she looked so wan he began to think he might have to move without finding a job first.

That thought was frightening, but not as frightening as the thought of losing Cathie.

As she carried their plates to the table, Leah Willcox paused, as she often did, to stare out of the kitchen window at the moors. She loved to gaze down the slope and see their tiny village of Ellindale bordering the road down the hill. Such a pretty view! And such a nice set of neighbours. She loved living here.

Spring Cottage was the highest dwelling in the narrow Pennine valley. She’d grown up in the small town of Rivenshaw at the lower end, but after her marriage she’d fallen in love with the rolling open spaces of the Pennines, which stretched beyond their land across what locals called ‘the tops’. She’d hate to live anywhere else now.

After sitting down, she ate her first sandwich in a few hungry bites then sneaked a sideways glance at her husband. He’d taken a couple of small bites and pushed the rest of his to one side. Lately he’d only been picking at his food and it showed in the gaunt lines of his body.

‘If you don’t feel like cheese sandwiches, I could make you something else, Jonah.’

‘What? Oh, no thanks. I’m not all that hungry today.’

‘You need to eat to keep up your strength.’

‘Don’t fuss, dear.’

She suppressed a sigh and finished off her sandwiches before clearing the table. She was seriously worried about him. He’d made it clear to her when they entered into a marriage of convenience that he wasn’t . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...