- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

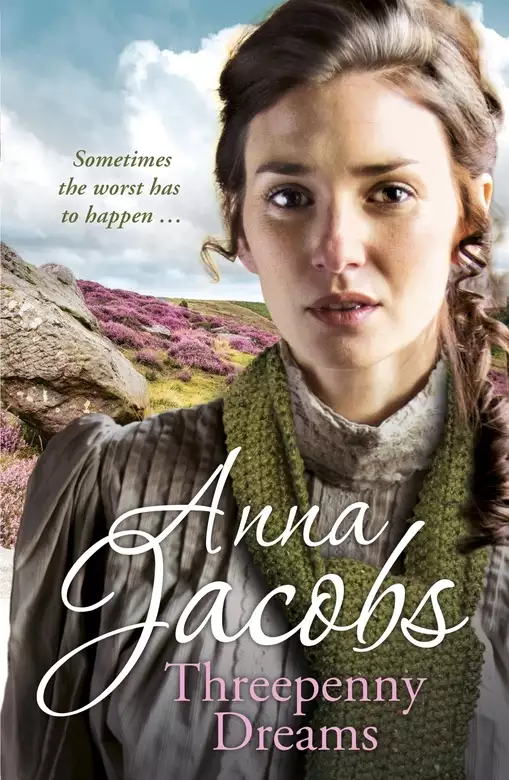

The final installment in Anna Jacobs' beloved Irish Sisters series.

Sometimes the worst has to happen....

Recently widowed, Hannah Firth is still young - young enough to dream of a new life. When her spiteful daughter-in-law uses her as an unpaid servant, Hannah tries to leave, but she is unaware of the depths that Patty's spite will lead her to.

Nathaniel King's life is ruined when his landlord's son lays waste to his market garden for a prank - and the resulting feud puts Nathaniel's livelihood at stake.

Hannah has only a few coins and dreams of a happier future to sustain her as she tramps the roads and evades pursuit. When she meets Nathaniel, the attraction between them cannot be denied, and they join forces. But their enemies have money and powerful allies on their side and will stop at nothing to get rid of them....

Release date: June 9, 2010

Publisher: Hodder & Stoughton

Print pages: 300

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Threepenny Dreams

Anna Jacobs

Hearing footsteps behind her, she swung round.

‘He’s gone, then?’ Her older son Lemuel stared at her from the doorway.

She nodded, not trusting her voice. She had dreaded this since her husband’s death: living in a house which now belonged to her son and his shrew of a wife, being dependent on them for her daily existence, with no one to take her side if there were disagreements – especially with a daughter-in-law like hers.

Patty pushed her husband aside and came into the room, looking round with the proprietorial air which had already begun to irritate Hannah. ‘Well, maybe now you’ll notice that you have another son, Mother Firth, one who’s worth ten times as much as your precious Malachi.’

‘I love both my sons,’ Hannah said, keeping her voice steady only with a huge effort, ‘but I can surely be allowed to grieve for the one I’ve lost.’

Lemuel moved across to pat her awkwardly on the shoulder, a tall young man of twenty-three already well on the way to being as heavy as his father. She’d been eighteen when she’d borne him, a child herself still in many ways with only strangers to help her through this terrifying and painful experience. Her husband had been forty-two, the same age as she was now. Strange that he had seemed so old then when she still felt young.

John had been a steady, dependable man and Lemuel was just the same. He would run the cooperage exactly as his father had. They were both dull, so very dull, with minds that ticked along slowly and an old-fashioned approach to life. She wished, as she had many times, that her parents hadn’t pushed her into marriage at seventeen with a man so much older than herself. John had been kind enough, treating her more like a pet than a wife at first, but always expecting her life to revolve round his needs as master of the house.

‘I’d better go and open up the workshop. Those barrels won’t make themselves.’

She watched Lemuel leave. He didn’t look back, his mind already set on the day’s tasks.

‘Well, no use moping, Mother Firth,’ Patty said briskly. ‘We have plenty to do. First I want you to clear up the kitchen while I feed little John, then we’ll think about today’s meals. And, of course, there’s Malachi’s room to clear out. It’ll make a fine nursery.’

‘I’ll do that,’ Hannah said quickly.

‘No, I’ll do it later. I want to rearrange the furniture.’

Patty looked at her challengingly, as if she would relish an argument, so Hannah bit her tongue and got on with clearing up the kitchen. She paused for a moment to stare round before she started work. It was only two days since her son and his wife had moved in and already Patty had set her mark on what had been Hannah’s domain for over twenty years, rearranging everything, whether it needed it or not.

Why could her husband not have left her some money of her own, just a little, so that she could have rented a cottage and lived in peace? She wasn’t greedy, wouldn’t have needed much, but all she had now was what she’d saved over the years from the housekeeping money, and she’d dipped deeply into that to help Malachi buy some trading goods to take with him to Australia.

She sighed and closed her eyes for a moment. Perhaps she should have kept more of the money for herself, but she’d wanted him to get a good start. He’d had such dreams of making a new life for himself in a land full of sunshine. She smiled at the thought. The two of them had a name for big, important dreams like that: threepenny dreams. She and Malachi were alike in so many ways, interested in the wider world, needing to feed their brains as well as their bodies.

Who would she share her dreams with now? It suddenly occurred to her that she had none left for herself anyway, not even a halfpenny one. She still felt numb, because John’s death had been so unexpected. As she looked out of the window at the grey skies she shivered, though it was warm enough in the kitchen. No wonder Malachi hankered for sunshine. It seemed to have been raining for weeks, even though it was high summer.

She sighed as she began to gather the dirty dishes together. How was she to face years of being subservient to Patty? Other women coped with this situation when they were widowed, but . . . she froze as she realised suddenly that she simply couldn’t endure it. Those other women didn’t have Patty for a daughter-in-law.

She’d have to work out what to do instead. She would put up with things for a while until she saw her way clear to making a new life for herself. After all, she was young for her years, still strong and energetic like all the women of her family. There were only a few grey threads in her dark hair and she was as slender as any girl in the village. Surely she would have no difficulty in finding employment?

Another thought slipped into Hannah’s mind unbidden: or even a new husband. No, she was too old for that. And she could never marry for mere convenience, not again.

A wry smile twisted her face. Getting away from Patty was only a penny dream, because there was no joy in it, but it’d do for a start. Taking a deep breath, Hannah carried hot water through to the scullery and poured it into the tin bowl in the slopstone, tossing in some soda crystals.

When Patty didn’t join her, she guessed that her daughter-in-law was delaying, waiting for her to finish. Patty was lazy about housework. Hannah had suspected it for years but it hadn’t mattered when the other woman lived in her own house. It would matter now, though, if her daughter-in-law tried to treat her as an unpaid servant.

She’d have to find a way to escape or she’d go mad.

The following day was fine and when Patty started complaining and scolding, Hannah suddenly couldn’t stand it a minute longer. She was still grieving for Malachi, still trying to get used to her new status. Holding her head high, she walked into the kitchen, slipped her old shawl off the hook by the door and went out through the rear garden. Ignoring the shrieks of ‘Where are you going?’ then ‘Come back at once!’ from behind her, she walked past the cooper’s workshop where her son was moving about purposefully and left by the back gate.

Following the narrow laneway behind it, Hannah slowed down as she passed the last building in the village: the workhouse built for the six neighbouring parishes on a patch of sour land. It was an ugly place, widely detested by those living hereabouts, and Hannah remembered when she was a girl how strong resistance had been in the area to complying with the new Poor Law Act, and how it had taken nearly ten years for the Assistant Commissioners appointed by London to bring her own Hetton-le-Hill and the nearby parishes into line with the law.

As she walked past the high stone wall, topped by broken glass, she shivered. It was such a dreary, hopeless place, looked unwelcoming and was, apparently, even worse inside. It housed not only paupers but idiots, lunatics and unmarried mothers, the least fortunate of the six parishes. And everyone knew how strictly its inmates were treated.

‘Poor souls!’ she muttered, as she always did when she passed this place. Things were even worse there now since the new parson had become Chairman of the Board of Guardians. She didn’t like Parson Barnish, who seemed to her to act scornfully towards his poorer parishioners.

As she strode up towards the moors that overlooked her village, she took deep breaths of the clean air, enjoying the wind and the shifting shadows of the clouds rolling across the tops. Her thoughts were not so pleasant. She’d known it would be difficult to live with her daughter-in-law, but already it was proving far harder than she’d expected. To be ordered around like a half-witted drudge outraged her – and was in no way necessary because she had always prided herself on being a good housekeeper, and indeed, was more used to being asked for advice than told what to do.

Breathless, she stopped at an outcrop of rocks and sank down, brushing the tears away from her eyes with her fingertips. What good did it do to weep? She’d learned that when first married. She leaned back, closing her eyes, enjoying the quiet sounds of nature. The breeze whispered around her and somewhere above a bird was calling, its voice full of fluting silver joy. Sunlight warmed her face intermittently as clouds shaded then revealed the sun. Relaxing, she let herself drift into a doze.

‘You all right, missus?’

‘What? Oh!’ She jerked awake to find a man staring down at her anxiously, one of the local shepherds whom she knew by sight. ‘Yes, I’m fine. Just tired.’

‘It’ll be coming on to rain soon. You’d better get yoursen home, Mrs Firth.’

She tried desperately to remember his name.

He smiled as if he could read her thoughts. ‘I’m Tad Mosely. I’ve dealt with your husband a time or two. Do you need a hand to get up?’

She shook her head. ‘No, thank you, Tad. I’ll just sit here a little longer, then I’ll go back.’

‘Don’t leave it too long. Look at them rain clouds gathering.’ He hesitated then added, ‘I’m sorry about your husband. He were a decent fellow. You’re allus welcome to stop off at our hut if you’re out walking on the tops. We can usually find a cup of tea for a friend.’ He waved in the direction of a small grey-stone building higher up the moor, a shepherd’s shelter, gave her a nod of farewell then whistled to his dogs and strode off.

She pulled the shawl more tightly around her shoulders, shivering in the cold, moist air as more clouds gathered in the sky, dark ones this time.

Not until rain began falling did she start back, not caring whether she got soaked or not, her steps slow and reluctant.

Life could be cruel. This was the second time fate had been unkind to her. She had remembered the first every time she’d looked at Malachi whose face was so like his father’s – and so unlike her husband’s.

That night in bed Patty said, ‘I’m worried about your mother, Lemuel. She’s getting very vague. And she stayed out today even though she must have seen it was going to rain. She was absolutely soaked when she got back. Why did she want to go walking on the moors anyway? I need her help here. She forgets how much extra work a baby makes.’

He let the words flow past him, as he’d learned to do. He wished she didn’t always see the worst in people, wished she’d be kinder to his mother. But if he said that, it’d only make her worse.

When she stopped talking he reached for her. They’d agreed to try for another baby. Well, he’d said he wanted more children and she’d said she’d have one more and then see how things went. She put up with his fumblings, so that he finished feeling slightly ashamed, as usual, but at least he’d got his relief.

In the village of Marton, on the other side of Preston, Nathaniel King looked up at the sky. Past noon. Time to go back to the house and get his wife something to eat. Not that she’d eat much. She had little appetite these days and was almost skeletal in appearance. Poor Sarah had never been strong, but now the doctor said her heart was failing and the end couldn’t be far away.

Inside the small stone farmhouse he went into the room which served as both kitchen and parlour, because they rarely used the small, chilly front room on the north side of the house. He found Sarah lying on the daybed gazing dreamily out of the window. She didn’t notice him come in and when he laid one hand on her arm, she jumped in shock.

‘Time for dinner, love. I’ll just wash my hands.’

‘I don’t want anything, Nathaniel.’

‘You have to eat, Sarah.’

‘Why?’

‘You can’t just – give up.’

‘I can. I have. I’ve been thinking about it all week and if I don’t want to eat, I shan’t from now on. Please don’t try to make me because I won’t do it, even for you.’

‘But, Sarah, love . . .’

‘Nathaniel, I’m just a burden to you, and as for poor Gregory – well, a lad of ten shouldn’t have to watch his mother die inch by inch, should he? And I’m finding life – difficult. So the quicker I can go the better.’

‘Oh, Sarah.’ He sat down beside her and took her hand in his. Once they had been very much in love but after several years of her being ill, that bright feeling had faded to a mere fondness on his part and he didn’t know what on hers. She had an air of otherworldliness now, as if she were not really part of this life, as if she were seeing things no one else could. And she was right: Gregory was suffering. Watching his mother die was bound to upset a lad. How long was it since Nathaniel had heard his son laugh?

‘How are the strawberries coming on?’ she asked after a while.

‘Well enough. I shall have another load to send to market by the end of the week.’

She nodded and her gaze slid back to the view from the window: neat rows of vegetables and a border of flowers close to the house, which her husband had planted specially because he knew how much she loved them.

Nathaniel stood for a minute surveying his small kingdom, as he liked to call it, making a play on his surname. He’d never thought to become a market gardener, having grown up on what he still thought of as a ‘proper farm’. But his father had died when he was only sixteen, so he’d lost the chance to carry on the lease. He and his mother had moved to Preston for a while, but he’d hated living in a town so he’d worked hard, saved his pennies and found a way to return to the country after his mother died.

Growing vegetables and fruit paid quite well nowadays because here in Marton they were within easy reach of industrial Preston. There seemed to be an insatiable demand for food in the expanding textile centres of Lancashire, plus a ready supply of fertiliser coming back to the country from the dairy animals which were still kept in the town so that the richer folk could have fresh milk. He himself thought it a shame to keep the poor cows penned up all the time and would never keep a living creature away from the sunlight like that.

But even though he brought in good money, at the moment most of it went to pay for help with the household tasks like washing and care of his wife, so he never managed to get much ahead or afford the improvements he yearned to make, the things he read about in newspapers or heard spoken of on his occasional visits to Preston. And even if he did propose such improvements, he wasn’t sure his landlord would let him change anything.

Richard Dewhurst was a decent man, who had made a fortune in cotton and then married a lady-wife and bought the estate which included Marton Hall, but he hadn’t spent a lot of time there. His wife had only given him two sons and had died years before, after which the nanny had brought up the younger boy and the older son had run wild. Nathaniel had heard recently that Dewhurst had come home to stay this time. Well, he was nearing seventy, time to leave others to manage his cotton mills surely? He’d recently been appointed a local magistrate, but it remained to be seen how well he’d fulfil that role.

The two sons lived permanently at Marton Hall. Walter, the elder, had only grown nastier as he grew into manhood and like the other tenants, Nathaniel avoided him as much as possible. Apart from making a nuisance of himself with young women, whether they were willing or not, he’d recently developed one of his sudden passions – this time for hunting what he called ‘ground game’. This entailed barging through people’s fences and crops to kill rabbits, hares and the very occasional fox, leaving a trail of destruction behind him. People hadn’t dared complain to the father, sure it’d only bring more trouble down on them, because Walter was known for getting his own back on those who’d offended him. And after all, the land agent always paid compensation for the damage, didn’t he?

Nathaniel wasn’t sure he could stand by and let Walter Dewhurst damage his land and crops, but luckily the fellow had never come near his smallholding.

The younger Dewhurst son, Oliver, was as unlike his brother as a primrose to a pig. He had been ill a lot when younger and you could see the lines of suffering on his face, though he had grown into quite a good-looking fellow and seemed in much better health nowadays. Pity he wouldn’t be the one to inherit because he had a kindly nature, sending help to folk in trouble and speaking to the tenants politely.

After another futile attempt to persuade Sarah to eat something Nathaniel spent the afternoon digging and watching old Tom Ringley exhaust himself trying to weed the strawberries. He made no comment on this. Tom was past working, really, with little strength left in him, but all he asked was a bed in the barn, food for his bent old body and the odd screw of tobacco, so Nathaniel continued to employ him. Like many old people, Tom’s main concern was not to be put in the poorhouse.

Well, you were a poor sort if you couldn’t offer that much, at least, to a man who had taught you how to grow fruit and vegetables, a man who’d once been as tall and strong as Nathaniel himself and who had shared his knowledge so generously all those years ago. And there were times, even now, when Tom Ringley knew the answer to a problem or how to deal with a pest that was attacking a crop when no one else did. Nathaniel loved to see the old fellow’s delight when this happened.

Hannah found that it grew harder, not easier, living with Patty. Her daughter-in-law was openly hostile when no one was around, snapping orders and doing as little as possible herself because she said the baby took up her time. But John was the quietest baby Hannah had ever seen and little trouble to anyone.

One day she went into her bedroom to fetch a clean handkerchief and found Patty there, going through her top drawer.

‘What are you doing?’

Patty turned to stare at her, not seeming in the least embarrassed to be caught ferreting through someone else’s things. ‘Seeing what you’ve got. I like to know everything that goes on in my own house.’

Hannah watched her saunter out then sank down on the bed, shocked to her core to think of someone doing such a thing.

She waited until they were all eating their evening meal that night before saying quietly but clearly, ‘If I’m not to have the privacy of my own room, then I’m not staying here.’

There was a pregnant silence. Patty threw her an angry glance. Lemuel looked from one woman to the other then said quietly, ‘Of course that room is your own, Mam, yours to do with as you wish. How do you lack privacy?’

‘I caught your wife going through my drawers.’

He turned to stare in shock at Patty, who sniffed and repeated, ‘I have a right to know what goes on in my own house.’

‘Nay, love, that’s a bit much. I’d never think of going through my mother’s things and you shouldn’t neither.’

She stared at him through narrowed eyes, shoved her chair back and jumped to her feet, shouting in a shrill voice, ‘Either this is my house or it’s not! Make up your mind, Lemuel! But if it’s not, then don’t expect me to do a hand’s turn here.’ Then she burst into tears and stormed upstairs to their bedroom.

He got to his feet, looking unhappily at his mother. ‘I know she’s being unreasonable, but I don’t want to upset her at the moment. We’re trying for another baby and, well, you know what it’s like.’

He followed his wife upstairs and angry voices floated down. Hannah tried not to listen, but was shocked at the way Patty berated her husband, shocked too at the things her daughter-in-law said about her, hinting that she was trying to evade her share of household duties and growing absent-minded.

When Lemuel came down again, he avoided his mother’s eyes and went on with his now cold meal.

‘It’ll get better,’ he offered as he went across to sit in the big armchair by the fire. ‘We’ll all shake down together if we give it a chance.’

Automatically Hannah started clearing up the tea things and getting ready to wash the dishes. ‘She still has no right to go through my things.’

He sighed. ‘I doubt you’ll stop her. She allus has to know. It’s how she’s made. You’ll get used to it. After all, you’ve got nothing to hide, have you, so it doesn’t really matter.’

Hannah went to bed early that night, as she usually did now, trying to read one of her few treasured books by the light of a single candle, but putting it down with a sigh when the words refused to register. If she hadn’t come into the room just then, Patty would have found her savings and no doubt tried to claim them for the family’s use. Hannah would take the money round to her friend Louisa’s the very next day and leave it there for safety. They’d known one another since they were girls and she trusted her friend completely.

She blew out the candle and slid down in bed, but her mind wouldn’t be still. She couldn’t continue like this, would have to find a job to take her away from here. She’d ask in the village, see if anyone knew of a housekeeping job going, and she wouldn’t say anything to Lemuel until she’d found herself something.

The following day Patty was even more waspish than usual, banging pots around, snapping out orders, criticising anything and everything.

After they’d cleared up the midday meal, Hannah took off her apron. ‘I’m going out for a while.’

‘I need you here, Mother Firth.’

‘Then you’ll have to do without me. I’m not a slave, Patty, not to anyone, and I work hard enough to deserve the odd hour or two off.’

‘You should be glad to repay us for all we spend on you.’

‘And you should remember that I’m not and never shall be your servant.’ She took her good shawl from her bedroom, put on her bonnet and came out again with her savings in her pocket, certain that Patty would finish going through her things once she was out.

‘Where are you going?’

‘That’s my business.’ She blinked in shock as her daughter-in-law thrust herself in front of the door.

‘I will know what you’re doing. I’m mistress of this house and—’

Taller and stronger, Hannah set her aside quite easily and opened the door, holding it against the hand that tried to shut it in her face.

‘You’ll be sorry for this!’ Patty panted. ‘He listens to me not you now. You have to learn your place in my house and not try to boss me around.’

Hannah bit back hasty words about who was trying to boss whom and strode out, heading towards the south end of the village. At the corner she glanced back and saw her daughter-in-law standing at the gate, watching her to see where she went. In a spirit of sheer devilment she walked right to the other end of the main street, then turned up the lane that led to the moors, but doubled back once she was out of sight to take the rear pathway to her friend Louisa’s house. When she got there, she rapped on the kitchen window, sure enough of her welcome to slip through the door without waiting to be invited inside.

‘Hannah, love. Eh! I thought you’d forgotten us.’ Louisa studied her friend’s face. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘I’m finding things – difficult at home. Today I just had to get away for a while.’

Louisa snorted. ‘You mean you’re finding Patty difficult to live with. I told you not even to think of staying there with them.’

‘I didn’t want to upset Lemuel, but you were right. I should have found myself a job straight off.’ Louisa had offered her a temporary home, but it had gone against the grain with Hannah to accept what felt like charity, even from her best friend.

Louisa bustled around, brewing a pot of tea and sitting across from her at the table to drink it. ‘That Patty’s just like her mother: takes umbrage if you speak and gets annoyed if you stay silent. You can never please folk like that. Mind you, I shouldn’t speak ill of poor Susan Riggs. They say she’s getting more forgetful every day.’ She tapped one finger to her forehead. ‘I hope I never lose my senses, I do indeed. It can be difficult for the family.’

‘Patty hasn’t said anything about her mother having problems.’ But then, Patty rarely spoke about her family.

‘Well, she wouldn’t, would she? The whole family’s trying to pretend it’s not happening. They’ll end up having to put Susan in the asylum, though, you mark my words. Softening of the brain, they call it. I’ve seen it afore. Some folk manage to look after them at home, but that sister of Patty’s is getting wed soon an’ she’ll be leaving the district so what’s to happen to Susan then?’

‘That sort of thing makes my own troubles seem less important.’

Louisa shook her head. ‘I don’t think so. You look fair worn down and it takes a lot to get you in that state, my lass. The question is, what are you going to do about it?’

‘Well, first I’m going to ask you to look after my savings. She’s started going through my drawers now and I’m sure she’d try to take the money if she found it.’ Hannah blinked away a tear of shame at this admission.

‘Oh, love, surely even she wouldn’t do that?’

Hannah had to swallow hard and dig her fingernails into her hands to prevent herself from weeping. There was nothing like a bit of sympathy for making you lose control of yourself. She fumbled in her pocket and held out the worn purse, trying to make a joke of it. ‘Here it is: all my worldly wealth.’

Louisa took the purse. ‘I’ll put it in my bottom drawer and only George will know it’s there. He won’t say a word, you can be sure.’ She reached out to clasp her friend’s hand for a moment. ‘What else?’

‘I was wondering if you knew of anyone looking for a housekeeper. You have such a lot of relatives and you’re always first with any news.’

‘Good idea. Anyone would be lucky to get you. I’ll ask around.’

‘Do it quietly. I don’t want to upset her before I have to.’

Three days later, Patty came home from visiting a friend and stormed into her husband’s workshop, cheeks flaring red. ‘Do you know what your mother is doing? Shaming us, that’s what. I’ve never been so embarrassed in my whole life as I was this afternoon when I found out.’

He blinked at her in shock, put down the long knife he was using to hollow out the barrel staves and jerked his head to the lad he’d taken on as an apprentice in a silent command to make himself scarce. ‘What are you talking about, love? My mother would never do anything to shame us. Eh, you’ve got a right down on her lately.’

‘That’s because you never really know someone until you have to live with them,’ she said ominously, scowling at him.

When he put his arm round her shoulders, she shook it off and began to pace up and down.

‘Tell me, then.’

‘Your mother’s looking for a job as a housekeeper and if that’s not shaming us, I don’t know what is.’

Lemuel stared at her in dismay. ‘She’d never do that. This is her home.’

‘Come and ask her then.’

‘I’ll see her tonight.’

‘You’ll see her now! This needs sorting out. And I warn you, I’m not having it!’

Sighing, he followed his wife into the house, wishing she were just a bit less sharp with the world.

Patty burst into the kitchen, finding Hannah with little John on her knee, the two of them laughing at one another. She snatched her baby from his grandmother’s arms, holding him so tightly he began to cry, and said dramatically, ‘Go on! Ask her, Lemuel!’

Hannah stared in shock from one to the other, her heart sinking at the expression on the younger woman’s face. ‘What’s wrong?’

Lemuel cleared his throat. ‘Patty’s heard – I’m sure it’s not true, Mam – but she’s heard that you’re looking for a job as a housekeeper.’

Hannah sighed as she looked at her earnest, rather sheep-like son. She’d rather have presented them with a fait accompli. ‘It is true.’

His face crumpled. ‘But Mam, why? You have a home here, you know you do. There’s no need for you to seek employment. Tell her, Patty!’

‘No need at all, Mother Firth. I’m upset you’d even think of leaving . . . shaming us in front of our neighbours like that!’

Hannah tried for diplomacy. ‘I think it’s better for a young couple to be together, without other relatives, especially if you’re trying for another baby.’

‘But Mam—’

She held up one hand and Lemuel fell silent. ‘And there’s my side to consider. I think I’d like to do something –’ she hesitated, searching for a phrase that wouldn’t give offence, but not finding one ‘– more interesting with my life than stay here in the back room until I die. I don’t feel old, Lemuel. I don’t feel old at all.’

Patty burst into loud tears and cast herself and her son into her husband’s arms. ‘I shall die of shame.’

He looked at his mother severely across the tops of their heads. ‘I won’t have it, Mam! Patty’s right. It is shaming for you to do such a thing.’

She sighed, realising she had to say it bluntly. ‘Lemuel, Patty has her own way of doing things and I find I don’t take to being ordered around. It’ll be bett

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...