- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

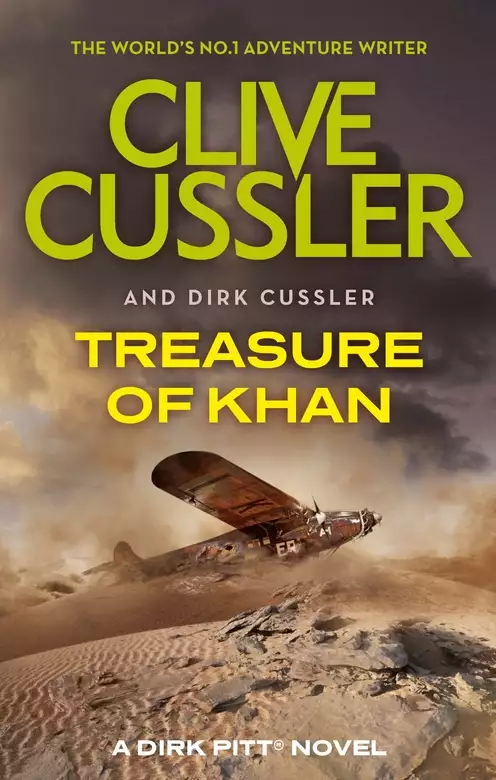

Genghis Khan was the greatest conqueror of all time, who, at his peak, ruled an empire that stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the Caspian Sea. His conquests are the stuff of legend, his tomb a forgotten mystery. Until now.

When Dirk Pitt is nearly killed rescuing an oil survey team from a freak wave on Russia's Lake Baikal, it appears a simple act of nature. When the survey team is abducted and Pitt's research vessel is nearly sunk, however, it's obvious there's something more sinister involved. All trails lead to Mongolia, and a mysterious mogul who is conducting covert deals for supplying oil to the Chinese while wreaking havoc on global oil markets utilizing a secret technology. The Mongolian harbors a dream of restoring the conquests of his ancestors, and holds a dark secret about Genghis Khan that just might give him the wealth and power to make that dream come true.

From the frigid lakes of Siberia to the hot sands of the Gobi Desert, Dirk Pitt and Al Giordino find intrigue, adventure, and peril while collecting clues to the mysterious treasure of Xanadu. But first, they must keep the tycoon from murder — and the unleashing of a natural disaster of calamitous proportions.

Filled with breathtaking suspense and brilliant imagination, this novel is yet further proof that when it comes to adventure writing, nobody beats Clive Cussler.

Take another thrill ride with Dirk Pitt.

Release date: November 28, 2006

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 624

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Treasure of Khan

Clive Cussler

HAKATA BAY, JAPAN

ARIK TEMUR PEERED INTO THE darkness and tilted his head toward the side rail as the sound of oars dipping through the water grew louder. When the noise closed to within a few feet, he slouched back into the shadows, pulling his head down low. This time the intruders would be welcomed aboard warmly, he thought with grim anticipation.

The slapping of the oars ceased, but a wooden clunk told him the small boat had pulled alongside the larger vessel’s stern. The midnight moon was a slim crescent, but crystal clear skies amplified the starlight, bathing the ship in a cottony luminance. Temur knelt quietly as he watched a dark figure climb over the stern rail, followed by another, then another, until nearly a dozen men stood on the deck. The intruders wore brightly colored silk garments under tunics of layered leather armor that rustled as they moved. But it was the glint of their razor-sharp katanas, single-edged dueling swords, that caught his eye as they assembled.

With the trap set and the bait taken, the Mongol commander turned to a boy at his side and nodded. The boy immediately began ringing a heavy bronze bell he cradled in his arms, the metallic clang shattering the still night air. The invaders froze in their tracks, startled by the sudden alarm. Then a hidden mass of thirty armed soldiers sprang silently from the shadows. Armed with iron-tipped spears, they flung themselves at the invaders, thrusting their weapons with deadly fury. Half of the boarders were killed instantly, struck by multiple spear tips that skewered their body armor. The remaining invaders wielded their swords and tried to fight back but were quickly overpowered by the mass of defenders. Within seconds, all of the boarders lay dead or dying on the ship’s deck. All, that is, except a lone, standing dervish.

Clad in an embroidered red silk robe with baggy trousers tucked into bearskin boots, he was clearly no peasant soldier. With devastating speed and accuracy, he surprised the attacking defenders by turning and running right into them, deflecting spear thrusts with quick waves of his sword. In an instant, he closed on a group of three of the ship’s defenders and quickly dropped them all to the deck with a flash of his sword, nearly cutting one man in two with a single swipe of the blade.

Watching the whirlwind decimate his soldiers, Temur jumped to his feet and unsheathed his own sword, then leaped forward. The swordsman saw Temur charge at him and deftly parried a spear thrust aside before whirling around and plunging his bloodied sword in the path of the oncoming warrior. The Mongol commander had killed more than twenty men in his lifetime and calmly sidestepped the swinging blade. The sword tip whisked by his chest, missing the skin by millimeters. As his opponent’s sword passed, Temur raised his own blade and thrust it tip first into the attacker’s side. The invader stiffened as the blade tore through his rib cage and bisected his heart. He bowed weakly at the Mongol as his eyes rolled back, then he fell over dead.

The defenders let out a cheer that echoed across the harbor, letting the rest of the assembled Mongol invasion fleet know that the guerrilla attack this night had failed.

“You fought bravely,” Temur complimented his soldiers, mostly Chinese, who gathered around him. “Throw the bodies of the Japanese into the sea and let us wash their blood from our decks. We may sleep well and proud tonight.” Amid another cheer, Temur knelt next to the samurai and pried away the bloodstained sword clasped in the dead man’s hands. In the dim light of the ship’s lanterns, he carefully studied the Japanese weapon, admiring its fine craftsmanship and razor-sharp edge, before sliding it into his own waist scabbard with a nod of satisfaction.

As the dead were unceremoniously dumped over the side, Temur was approached by the ship’s captain, a stern Korean named Yon.

“A fine battle,” Yon said without empathy, “but how many more attacks on my ship must I endure?”

“The land offensive will regain momentum once the South of the Yangtze Fleet arrives. The enemy will soon be crushed and these raiding attacks will cease. Perhaps our entrapment of the enemy tonight will prove to be a deterrent.”

Yon grunted in skepticism. “My ship and crew were to have been back in Pusan by now. The invasion is turning into a debacle.”

“While the arrival of the two fleets should have been better coordinated, there is no question as to the ultimate outcome. Conquest shall be ours,” Temur replied testily.

As the captain walked away shaking his head, Temur cursed under his breath. Reliant on a Korean ship and crew and an army of Chinese foot soldiers with which to do battle was like having his hands tied behind his back. Land a division of Mongol cavalry, he knew, and the island nation would be subdued in a week.

Wishing would not make it so, and he begrudgingly considered the validity of the captain’s words. The invasion had in fact started off on a shaky footing, and, if he was superstitious, he might even think there was a curse on them. When Kublai, emperor of China and khan of khans of the Mongol Empire, had requested tribute from Japan and been rebuffed, it was only natural to send an invasion fleet to subdue their insolence. But the invasion fleet sent in 1274 was much too small. Before a secure beachhead could be established, a severe gale battered the Mongol fleet, decimating the warships as they stood out at sea.

Now, seven years later, the same mistake would not be made. Kublai Khan called for a massive invasion force, combining elements of the Korean Eastern Fleet with the main battle group from China, the South of the Yangtze Fleet. Over one hundred fifty thousand Chinese and Mongol soldiers would converge on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu to overrun the ragtag warlords defending the country. But the invasion force had yet to be consolidated. The Eastern Fleet sailing from Korea had arrived first. Pining for glory, they tried landing forces north of Hakata Bay but quickly ground down. In the face of a spirited Japanese defense, they were forced to pull back and wait for the second fleet to arrive.

With growing confidence, the Japanese warriors began taking the fight to the Mongol Fleet. Brazen raiding parties on small boats would sneak into the harbor at night and assault the Mongol ships at anchor. The gruesome discovery of decapitated bodies told the story of yet another attack by samurai warriors, who took the heads of their slain victims home as war trophies. After several guerrilla strikes, the invasion fleet began tying their ships together for protective safety. Temur’s entrapment ploy of mooring his ship alone at the edge of the bay had worked as anticipated, enticing a Japanese boarding party to their death.

Though the late-night attacks caused little strategic harm, they dampened the fading morale of the invading forces. The soldiers were still stationed aboard the cramped Korean ships nearly three months after departing Pusan. Provisions were low, the ships were rotting, and dysentery outbreaks were cropping up across the fleet. But Temur knew that the arrival of the South of the Yangtze ships would turn the tables. The experienced and disciplined force from China would easily defeat the lightly organized samurai warriors, once they were landed in mass. If only they would arrive.

The next morning broke sunny and clear, with a stiff breeze blowing from the south. On the stern of his mugun support ship, Captain Yon surveyed the crowded confines of Hakata Bay. The fleet of Korean ships was an impressive sight in its own right. Nearly nine hundred vessels stretched across the bay in an assortment of shapes and sizes. Most were wide and sturdy junks, some as small as twenty feet, others like Yon’s stretching nearly eighty feet long. Almost all had been constructed purposely for the invasion. But the Eastern Fleet, as it was known, would be dwarfed by the forces to come.

At half past three in the afternoon, a call rang out from a lookout, and soon excited cries and the sound of banging drums thundered across the harbor. Out to sea, the first dots of the southern invasion force appeared on the horizon crawling toward the Japanese coast. Hour by hour, the dots multiplied and grew larger until the entire sea seemed to be a mass of dark wooden ships with blood red sails. More than three thousand ships carrying one hundred thousand additional soldiers emerged from the Korea Strait, comprising an invasion fleet the likes of which would not be seen again until the invasion of Normandy almost seven hundred years later.

The red silk sails of the war fleet flapped across the horizon like a crimson squall. All night and well into the following day, squadron after squadron of Chinese junks approached the coast, assembling in and around Hakata Bay as the military commanders calculated a landing strike. Signal flags rose high on the flagship, where Mongol and Chinese generals planned a renewed invasion.

Behind the defenses of their stone seawall, the Japanese looked on in horror at the massive fleet. The overwhelming odds seemed to heighten the determination in some of the defenders. Others looked on in despair and desperately prayed for the gods to help through heavenly intervention. Even the most fearless samurai recognized that there was little likelihood they would survive the assault.

But a thousand miles to the south, another force was at work, more powerful even than the invasion fleet of Kublai Khan. A percolating mix of wind and sea and rain was brewing together, welding into a wicked mass of energy. The storm had formed as most typhoons do, in the warm waters of the western Pacific near the Philippines. An isolated thunderstorm set off its birth, upsetting the surrounding high-pressure front by causing warm air to converge with cold. Funneling warm air off the ocean’s surface, the churning winds gradually blew into a tempest. Moving unabated across the sea, the storm grew in intensity, exuding a devastating force of wind. Surface winds raged higher and higher, until exceeding one hundred sixty miles per hour. The “super typhoon,” as they are now branded, crept almost straight north before curiously shifting direction to the northeast. Directly in its path were the southern islands of Japan and the Mongol Fleet.

Standing off Kyushu, the assembled invasion force was focused only on conquest. Oblivious to the approaching tempest, the joint fleets assembled for a combined invasion.

“We are ordered to join the deployments to the south,” Captain Yon reported to Temur after signal flags were exchanged within his squadron. “Preliminary ground forces have landed and secured a harbor for unloading the troops. We are to follow portions of the Yangtze Fleet out of Hakata Bay and prepare to land our soldiers as reinforcements.”

“It will be a relief to have my soldiers on dry land again,” Temur replied. Like all Mongols, Temur was a land warrior used to fighting on horseback. Attacking from the sea was a relatively novel concept for the Mongols, adopted only in recent years by the emperor as a necessary means of subjugating Korea and South China.

“You shall have your chance to land and fight soon enough,” Yon replied as he oversaw the retrieval of his ship’s stone anchor.

Following the main body of the fleet out of Hakata Bay and along the coastline to the south, Yon looked uncomfortably at the skies as they blackened on the horizon. A single cloud seemed to grow larger and larger until it shaded the entire sky. As darkness fell, the wind and seas began to seethe, while sprays of rain slapped hard against the ship’s surface. Many of the Korean captains recognized the signs of an approaching squall and repositioned their ships farther offshore. The Chinese sailors, not as experienced in open-water conditions, foolishly held their positions close to the landing site.

Unable to sleep in his rollicking bunk, Temur climbed above deck to find eight of his men clinging to the rail, seasick from the turbulence. The pitch-black night was broken by dozens of tiny lights that danced above the waves, small candlelit lanterns that marked other vessels of the fleet. Many of the ships were still tied together, and Temur watched as small clusters of candlelight rose and fell as one on the rolling swells.

“I will be unable to land your troops ashore,” Yon shouted to Temur over the howling winds. “The storm is still building. We must move out to sea in order to avoid being crushed on the rocks.”

Temur made no effort to protest and simply nodded his head. Though he wanted nothing more than to get his soldiers and himself off the pitching ship, he knew an attempt to do so would be foolhardy. Yon was right. As miserable as the prospect sounded, there was nothing to do but ride out the storm.

Yon ordered the lugsail on the foremast raised and maneuvered the ship’s bow to the west. Tossing roughly through the growing waves, the sturdy vessel slowly began fighting its way away from the coastline.

Around Yon’s vessel, confusion reigned with the rest of the fleet. Several of the Chinese ships attempted to put troops ashore in the maelstrom, though most remained at anchor a short distance away. A scattering of vessels, mostly from the Eastern Fleet, followed Yon’s lead and began repositioning themselves offshore. Few seemed to believe that yet another typhoon could strike and damage the fleet as in 1274. But the doubters were soon to be proven wrong.

The super typhoon gathered force and rolled closer, bringing with it a torrent of wind and rain. Soon after dawn the sky turned black and the storm reared up with its full might. Torrential rains blew horizontally, the water pellets bursting with enough force to shred the sails of the bobbing fleet. Waves crashed to shore in thunderous blows that could be heard miles away. With screeching winds that exceeded a Category 4 hurricane, the super typhoon finally crashed into Kyushu.

On shore, the Japanese defenders were subject to a ten-foot wall of storm surge that pounded over the shoreline, inundating homes, villages, and defense works while drowning hundreds. Ravaging winds uprooted ancient trees and sent loose debris flying through the air like missiles. A continuous deluge of rain dumped a foot of water an hour on inland areas, flooding valleys and overflowing rivers in a deadly barrage. Flash floods and mud slides killed untold more, burying whole towns and villages in seconds.

But the maelstrom on shore paled in comparison to the fury felt by the Mongol Fleet at sea. In addition to the explosive winds and piercing rains came mammoth waves, blown high by the storm’s wrath. Rolling mountains of water belted the invasion fleet, capsizing many vessels while smashing others to bits. Ships anchored close to shore were swiftly blown into the rocky shoals, where they were battered into small pieces. Timbers buckled and beams splintered from the force of the waves, causing dozens of ships to simply disintegrate in the boiling seas. In Hakata Bay, groups of ships still lashed together were battered mercilessly. As one vessel foundered, it would pull the other ships to the bottom like a string of dominoes. Trapped inside the fast-sinking ships, the crew and soldiers died a quick death. Those escaping to the violent surface waters drowned a short time later, as few knew how to swim.

Aboard the Korean mugun, Temur and his men clung desperately to the ship as it was tossed like a cork in a washing machine. Yon expertly guided the vessel through the teeth of the storm, fighting to keep his bow to the waves. Several times, the wooden ship heeled so far over that Temur thought she would capsize. Yet there was Yon standing tall at the rudder as the ship righted itself, a determined grin on his face as he did battle with the elements. It wasn’t until a monster forty-foot wave suddenly appeared out of the gloom that the salty captain turned pale.

The huge wall of water bore down on them with a thunderous roar. The cresting wave swept onto the ship like an avalanche, burying the vessel in a froth of sea and foam. For several seconds, the Korean ship disappeared completely under the raging sea. Men belowdecks felt their stomachs drop from the force of the plunge and oddly noted the howl of the wind vanish as everything went black. By all rights, the wooden ship should have broken to pieces by the wave’s pounding. But the tough little vessel held together. As the giant wave rolled past, the ship rose like an apparition from the deep and regained her position on the frenzied sea.

Temur was tossed across the deck during the submersion and barely clung to a ladder rung as the ship flooded. He gasped for air as the vessel resurfaced and was distraught to see that the masts had been torn off the ship. Behind him, a sharp cry rang out in the water off the stern. Glancing about the deck, he realized with horror that Yon and five Korean seamen, along with a handful of his own men, had been swept off the ship. A chorus of panicked cries pierced the air momentarily before it was washed out by the howl of the wind. Temur caught sight of the captain and men struggling nearby in the water. He could only watch helplessly as a large wave carried them from his sight.

Without masts and crew, the ship was now at the complete mercy of the storm. Pitching and wallowing feebly in the seas, pounded and flooded by the high waves, the ship had a thousand opportunities to founder. But the simple yet robust construction of the Korean ship kept her afloat while around her scores of Chinese ships vanished into the depths.

After several intense, buffeting hours, the winds slowly died down and the pelting rains ceased. For a brief moment, the sun broke clear, and Temur thought the storm had ended. But it was just the eye of the typhoon passing over, offering a brief reprieve before the assault would continue again. Belowdecks, Temur found two Korean sailors still aboard and forced them to help man the ship. As the winds picked up and the rains returned, Temur and the sailors took turns tying themselves to the rudder and battling the deadly waves.

Lost as to position or even the direction they sailed, the men bravely focused on keeping the ship afloat. Unaware that they were now absorbing the counterclockwise winds that swirled from the north, they were pushed rapidly through open water to the south. The brunt of the typhoon’s energy had been expended as it struck Kyushu, so the battering was less intense than before. But gusts over ninety miles per hour still buffeted the vessel, blasting it roughly through the seas. Blinded by the pelting rain, Temur had little clue to their path. Several times the ship nearly approached landfall, inching by islands, rocks, and shoals that went unseen in the gloom of the storm. Miraculously, the ship blew clear, the men aboard never realizing how close they came to death.

The typhoon raged day and night before gradually losing its power, the rain and winds fading to a light squall. The Korean mugun, battered and leaky, held fast and clung to the surface with gritty pride. Though the captain and crew were lost and the ship was a crippled mess, they had survived all that the killer storm could throw at them. A quiet sense of luck and destiny settled over them as the seas began to calm.

No such luck befell the rest of the Mongol invasion force, which was brutally decimated by the killer typhoon. Nearly the entire Yangtze Fleet was destroyed, smashed to bits against the rocky shoreline or sunk by the vicious seas. A jumbled array of broken timber from huge Chinese junks, Korean warships, and oar-driven barges littered the shoreline. In the water, the cries of the dying had long since echoed over the shrieks of the wind. Many of the soldiers, clothed in heavy leather body armor, sank immediately to the bottom upon being cast in the waves. Others fought through the throes of panic to stay afloat, only to be pummeled by the endless onslaught of massive waves. The lucky few who crawled ashore alive were quickly cut up by marauding bands of samurai roving the shoreline. After the storm, the dead littered the beaches like stacked cords of wood. Half-sunken wrecks lined the horizon off Kyushu in such numbers that it was said a man could walk across the Imari Gulf without getting wet.

The remnants of the invasion fleet limped back to Korea and China with the unthinkable news that Mother Nature had again spoiled the Mongol plans of conquest. It was a crushing defeat for Kublai Khan. The disaster represented the worst defeat suffered by the Mongols since the reign of Genghis Khan, and showed the rest of the world that the forces of the great empire were far from invincible.

For the Japanese, the arrival of the killer typhoon was nothing less than a miracle. Despite the destruction incurred on Kyushu, the island had been spared conquest and the invading forces defeated. Most believed it could only have come as a result of the eleventh-hour prayers to the Sun Goddess at the Shrine of Ise. Divine intervention had prevailed, a sure sign that Japan was blessed with heavenly protection to ward off foreign invaders. So strong was the belief in the Kami-Kaze, or “divine wind” as it was called, that it permeated Japanese history for centuries, reappearing as the appellation for the suicide pilots of World War II.

• • • •

ABOARD THE Korean troopship, Temur and the surviving crew had no idea as to the devastation suffered by the invasion fleet. Blown out to sea, they could only assume that the invading force would regroup after the storm passed and continue the assault.

“We must rejoin the fleet,” Temur told the men. “The emperor is expecting victory and we must fulfill our duty.”

There was only one problem. After three days and nights of severe weather, tossed about without mast and sails, there was no telling where they were. The weather cleared, but there were no other ships in sight. Worse for Temur, there was nobody aboard capable of navigating a vessel at sea. The two Korean sailors who survived the storm were a cook and an aged ship’s carpenter, neither possessing navigation skills.

“The land of Japan must be to the east of us,” he conferred with the Korean carpenter. “Construct a new mast and sails, and we shall use the sun and stars to guide us east until we reach landfall and relocate the invasion fleet.”

The old carpenter argued that the ship was not seaworthy. “She is battered and leaking. We must sail northwest, to Korea, to save ourselves,” he cried.

But Temur would have none of it. A temporary mast was hastily constructed and makeshift sails raised. With a fresh determination, the Mongol soldier-turned-sailor guided the waylaid ship toward the eastern horizon, anxious to put ashore again and rejoin the battle.

• • • •

TWO DAYS passed, and all Temur and his men could see was blue water. The Japanese mainland never materialized. Thoughts of changing course were dispelled when yet another storm crept up on them from the southwest. Though less intense than the earlier typhoon, the tropical storm was widespread and slow moving. For five days, the troopship battled the throes of high winds and heavy rains that pitched them wildly about the ocean. The beaten ship seemed to be reaching its limits. The temporary mast and sails were again lost overboard to the gales, while leaks below the waterline kept the carpenter working around the clock. More disconcerting, the entire rudder broke free of the ship, taking with it two of Temur’s soldiers, who clung to it for dear life.

When it seemed that the ship could bear no more, the second storm quietly passed. But as the weather eased, the men aboard became more anxious than ever. Land had not been sighted in over a week and food supplies were beginning to dwindle. Men openly pleaded with Temur to sail the ship to China, but the prevailing winds and current, as well as the lack of a ship’s rudder, made that impossible. The lone ship was adrift in the ocean with no bearings, no navigation aids, and little means to guide the way.

Temur lost track of time, as the hours drifted into days, and the days into weeks. With their provisions depleted, the feeble crew resorted to catching fish for food and collecting rainwater for drinking. The gray stormy weather was gradually replaced by clear skies and sunny weather. As the winds tapered, the temperature warmed. The ship seemed to grow stagnant along with the crew, drifting aimlessly under light winds over a flat sea. Soon a death cloud began to hover over the vessel. Each sunrise brought the discovery of a new corpse as the starving crewmen began to perish in the night. Temur looked over his emaciated soldiers with a feeling of dishonor. Rather than die in battle, their fate was to starve on an empty ocean far from home.

As the men around him dozed in the midday sun, a sudden clamor erupted on the port side deck of the ship.

“It’s a bird!” someone cried. “Try to kill it.”

Temur lurched to his feet to see a trio of men attempting to surround a large, dark-billed seagull. The bird hopped around spastically, eyeing the hungry men with a wary look. One of the men grabbed a wooden mallet with a gnarled sunburned hand and flung it swiftly at the bird, hoping to stun or kill it. The gull deftly sidestepped the flying mallet and, with a loud squawk of indignation, flapped its wings and rose lazily into the sky. While the disgruntled men cursed, Temur quietly studied the gull, his eyes following the white bird as it flew south and gradually melted into the horizon. Squinting at the far line of blue where the water met the sky, he suddenly arched a brow. Blinking forcefully, he looked again, tensing slightly when his eyes registered a small green lump on the horizon. Then his nose joined in on the fantasy. Temur could smell a difference in the air. The damp salt air that his lungs had become used to now had a different aroma. A sweet, slightly flowery fragrance wafted through his nostrils. Taking a deep breath, he cleared his throat and grumbled to the men on the deck.

“There is land before us,” he said in a parched voice, pointing toward the path of the gull. “Let every man who is able help guide us to it.”

The exhausted and emaciated crew staggered to life at the words. After straining their eyes at the distant speck on the horizon, the men gathered their wits and went to work. A large deck-support beam was sawed loose and manhandled over the stern, where, secured with ropes, it would act as a crude rudder. While three men wrestled the beam about to steer the ship, the remaining men attacked the water. Brooms, boards, and even sabers were used as makeshift oars by the desperate men in a struggle to row the battered vessel to land.

Slowly the distant spot grew larger, until a shimmering emerald island materialized, complete with a broad, towering mountain peak. Approaching the shoreline, they found heaving waves battering a rocky coastline, which rose up vertically. In a panicked moment, the ship became caught in a crosscurrent that drove them toward an inlet surrounded by jagged boulders.

“Rocks ahead!” the old ship’s carpenter cried, eyeing the protrusions off the bow.

“Every man to the left side of the ship,” Temur bellowed as they bore down on a dark wall of rock. The half-dozen men on the starboard railing ran, scampered, and crawled to the port side and frantically slapped the water with their makeshift oars. Their last-second surge nosed the bow away from the rocks, and the men held their breath as the port hull scraped against a line of submerged boulders. The grinding ceased, and the men realized that the ship’s timbers had held together once more.

“There is no place to put ashore here,” the carpenter shouted. “We must turn and go back to sea.”

Temur peered at the sheer rock cliff rising above the shore. Porous black and gray rock stretched in a high jagged wall in front of them, broken only by the small black oval of a cave, cut off their port bow at the waterline.

“Bring the bow around. Row again, men, at a steady pace.”

Clawing at the water, the drained men propelled the boat away from the rocks and back into the offshore current. Drifting along the landmass, they saw that the towering shoreline eventually softened. Finally, the carpenter spat out the words the crew waited to hear.

“We can land her there,” he said, pointing to a large crescent-shaped cove cut into the shoreline.

Temur nodded, and the men guided the vessel toward shore, a final gust of energy flowing from their limbs. Paddling into the cove, the exhausted men drove the ship toward a sandy beach, until its barnacle-encrusted hull ground to a halt a few feet from shore.

The weary men were nearly too spent to climb off the ship. Grabbing his sword, Temur painfully staggered ashore with five men to search for food and fresh water. Following the sound of rushing water, they cut through a thicket of tall ferns and found a freshwater lagoon, fed by a waterfall that rushed down a rocky ledge. In jubilance, Temur and his men plunged into the lagoon and happily gulped down mouthfuls of the cool water.

Their enjoyment was short-lived when a sudden pounding broke the air. It was the boom of the signal drum aboard the Korean ship, thumping out a cry to battle. Temur sprung to his feet in a single motion and called immediately to his men.

“Back to the ship. At once.”

He didn’t wait for his men to assemble but vaulted ahead in the direction of the ship. What

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...