- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A Sunday Times best seller

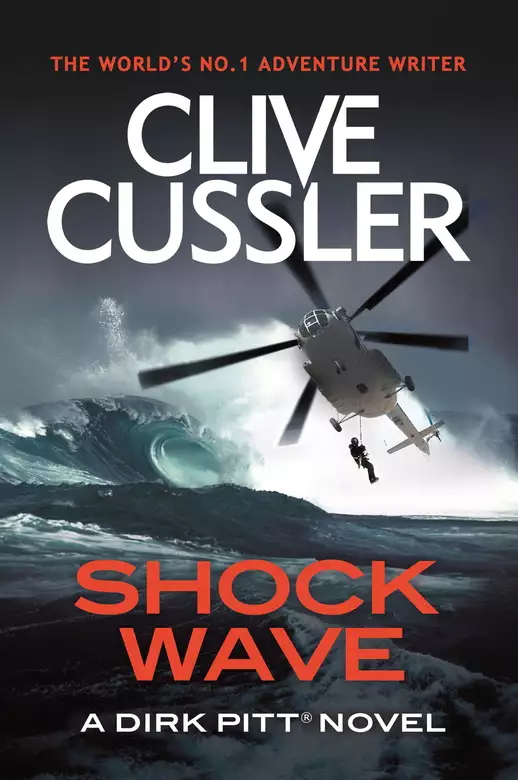

The 13th adrenaline-filled Dirk Pitt classic from multi-million-copy king of the adventure novel, Clive Cussler.

A hundred and forty years after a British ship wrecks on the way to an Australian penal colony and the survivors discover diamonds on the tropical island where they wash up, Maeve Fletcher, one of their descendants, is stranded on an island in Antarctica with a party of passengers after their cruise ship seemingly abandons them.

Dirk Pitt, on an expedition to find the source of a deadly plague that is killing dolphins and seals in the Weddell Sea, finds Maeve and the passengers and rescues them from death. When Pitt later uncovers the cause of the plague, he discovers that Maeve's father, Arthur Dorsett, and her two sisters are responsible because of their diamond-mining technology. A deadly race develops to stop Dorsett from continuing his murderous mining operations and to head off a disaster that will kill millions. Pitt's struggle to foil Dorsett's ruthless plan to destroy the market for diamonds and thus gain a monopoly of his own takes him from harrowing adventures off the west coast of Canada to being cast adrift in the Tasman Sea.

Release date: August 24, 2017

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Shock Wave

Clive Cussler

The Tasman Sea

Of the four clipper ships built in Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1854, one stood out from the others. She was the Gladiator, a big ship of 1,256 tons, 198 feet in length and a 34-foot beam, with three towering masts reaching for the sky at a rakish angle. She was one of the fleetest of the clippers ever to take to the water, but she was a dangerous ship to sail in rough weather because of her too fine lines. She was hailed as a “ghoster,” having the capability of sailing under the barest breath of wind. Indeed, the Gladiator was never to experience a slow passage from being becalmed.

Unfortunately, and unpredictably, she was a ship destined for oblivion.

Her owners fitted her out for the Australian trade and emigrant business, and she was one of the few clippers designed to carry passengers as well as cargo. But as they soon discovered, there weren’t that many colonists who could afford the fare, so she was sailing with first-and second-class cabins empty. It was found to be far more lucrative to obtain government contracts for the transportation of convicts to the continent that initially served as the world’s largest jail.

The Gladiator was placed under command of one of the hardest driving clipper captains, Charles “Bully” Scaggs. He was aptly named. Though Scaggs did not use the lash on shirking or insubordinate crewmen, he was ruthless in driving his men and ship on record runs between England and Australia. His aggressive methods produced results. On her third homeward voyage, Gladiator set a sixty-three-day record that still stands for sailing ships.

Scaggs had raced the legendary captains and clipper ships of his time, John Kendricks of the fleet Hercules and Wilson Asher in command of the renowned Jupiter, and never lost. Rival captains who left London within hours of the Gladiator, invariably found her comfortably moored at her dock when they arrived in Sydney Harbor.

The fast runs were a godsend to the prisoners, who endured the nightmarish voyages in appalling torment. Many of the slower merchant ships took as long as three and a half months to make the voyage.

Locked belowdecks, the convicts were treated like a cargo of cattle. Some were hardened criminals, some were political dissidents, all too many were poor souls who had been imprisoned for stealing a few pieces of cloth or scraps of food. The men were being sent to the penal colony for every offense from murder to pickpocketing. The women, separated from the men by a thick bulkhead, were mostly condemned for petty theft or shoplifting. For both sexes there were few conveniences of any kind. Skimpy bedding in small wooden berths, the barest of hygienic facilities and food with little nutrients was their lot for the months at sea. Their only luxuries were rations of sugar, vinegar and lime juice to ward off scurvy and a half-pint of port wine to boost their morale at night. They were guarded by a small detachment of ten men from the New South Wales Infantry Regiment, under the command of Lieutenant Silas Sheppard.

Ventilation was almost nonexistent; the only air came from hatchways with solidly built grills that were kept closed and heavily bolted. Once they entered the tropics, the air became stifling during the blazing hot days. They suffered even more during rough weather, cold and wet, thrown about by the waves crashing against the hull, living in a state of virtual darkness.

Doctors were required to serve on the convict ships, and the Gladiator was no exception. Surgeon-Superintendent Otis Gorman saw to the prisoners’ general health and arranged for small groups of them to come on deck for fresh air and exercise whenever the weather permitted. It became a source of pride for surgeons to boast, when finally reaching the dock in Sydney, that they hadn’t lost a prisoner. Gorman was a compassionate man who cared for his wards, bleeding them when required, lancing abscesses, dispensing treatment and advice on lacerations, blisters and purges, also overseeing the spreading of lime chloride in the water closets, the laundering of clothes and the scouring of the urine tubs. He seldom failed to receive a letter of thanks from the convicts as they filed ashore.

Bully Scaggs mostly ignored the unfortunates locked below his decks. Record runs were his stock in trade. His iron discipline and aggressiveness had paid off handsomely in bonuses from happy shipping owners while making him and his ship immortal in the legends of clipper ships.

This trip he smelled a new record and was relentless. Fifty-two days out of London, bound for Sydney with a cargo of trade goods and 192 convicts, 24 of them women, he pushed Gladiator to her absolute limits, seldom taking in sail during a heavy blow. His perseverance was rewarded with a twenty-four-hour run of an incredible 439 miles.

And then Scaggs’ luck ran out. Disaster loomed over the astern horizon.

A day after Gladiator’s safe passage through the Bass Strait between Tasmania and the southern tip of Australia, the evening sky filled with ominous black clouds and the stars were blotted out as the sea grew vicious in proportion. Unknown to Scaggs, a full-blown typhoon was hurling itself upon his ship from the southeast beyond the Tasman Sea. Agile and stout as they were, the clipper ships enjoyed no amnesty from the Pacific’s anger.

The tempest was to prove the most violent and devastating typhoon within memory of the South Sea islanders. The wind gained in velocity with each passing hour. The seas became heaving mountains that rushed out of the dark and pounded the entire length of the Gladiator. Too late, Scaggs gave the order to reef the sails. A vicious gust caught the exposed canvas and tore it to shreds, but not before snapping off the masts like toothpicks and pitching the shrouds and yards onto the deck far below. Then, as if attempting to clean up their mess, the pounding waves cleared the tangled wreckage of the masts overboard. A thirty-foot surge smashed into the stern and rolled over the ship, crushing the captain’s cabin and tearing off the rudder. The deck was swept free of boats, helm, deckhouse and galley. The hatches were stove in, and water poured into the hold unobstructed.

This one deadly, enormous wave had suddenly battered the once graceful clipper ship into a helpless, crippled derelict. She was tossed like a block of wood, made unmanageable by the mountainous seas. Unable to fight the tempest, her unfortunate crew and cargo of convicts could only stare into the face of death as they waited in terror for the ship to take her final plunge into the restless depths.

Two weeks after the Gladiator failed to reach port, ships were sent out to retrace the known clipper passages through Bass Strait and the Tasman Sea, but they failed to turn up a trace of survivors, corpses or floating wreckage. Her owners wrote her off as a loss, the underwriters paid off, the relatives of the crew and convicts mourned their passing and the ship’s memory became dimmed by time.

Some ships had a reputation as floating coffins or hell ships, but the rival captains who knew Scaggs and the Gladiator merely shook their heads and crossed off the vanished graceful clipper ship as a victim of her tender sailing qualities and Scaggs’ aggressive handling of her. Two men who had once sailed on her suggested that she might have been abruptly caught in a following gust in unison with a wave that broke over the stern, the combined force pushing her bow beneath the water and sending her plummeting to the bottom.

In the Underwriting Room of Lloyd’s of London, the famous maritime underwriters, the loss of the Gladiator was recorded in the logbook between the sinking of an American steam tugboat and the grounding of a Norwegian fishing boat.

Almost three years were to pass before the mysterious disappearance was solved.

Incredibly, unknown to the maritime world, the Gladiator was still afloat after the terrible typhoon had passed on to the west. Somehow the ravaged clipper ship had survived. But the sea was entering between sprung planks in the hull at an alarming rate. By the following noon, there were six feet of water in the hold, and the pumps were fighting a losing battle.

Captain Bully Scaggs’ flinty endurance never wavered. The crew swore he kept the ship from foundering by sheer stubbornness alone. He issued orders sternly and calmly, enlisting those convicts who hadn’t suffered major injuries from having been knocked about by the constant battering of the sea to man the pumps while the crew concentrated on repairing the leaking hull.

The rest of the day and night was spent in an attempt to lighten the ship, throwing overboard the cargo and any tool or utensil that was not deemed indispensable. Nothing helped. Much time was lost, and the effort achieved little. The water gained another three feet by the following morning.

By midafternoon an exhausted Scaggs bowed to defeat. Nothing he or anyone could do would save the Gladiator. And without boats there was only one desperate gamble to save the souls on board. He ordered Lieutenant Sheppard to release the prisoners and line them up on deck opposite the watchful eyes of his armed detachment of soldiers. Only those who worked the pumps and members of the crew feverishly attempting to caulk the leaks remained at their labor.

Bully Scaggs didn’t need the lash or a pistol to have complete domination of his ship. He was a giant of a man with the physique of a stonemason. He stood six feet two inches tall, with eyes that were olive gray, peering from a face weathered by the sea and sun. A great shag of ink-black hair and a magnificent black beard that he braided on special occasions framed his face. He spoke with a deep, vibrant voice that enhanced his commanding presence. In the prime of life, he was a hard-bitten thirty-nine years old.

As he looked over the convicts he was startled by the number of injuries, the bruises, the sprains, the heads wrapped with blood-soaked bandages. Fear and consternation were revealed on every face. An uglier group of men and women he’d never laid eyes on. They tended to be short, no doubt due to a lifetime of insufficient diet. Their countenances were gaunt, their complexions, pallid. Cynical, impervious to the word of God, they were the dregs of British society, without expectation of seeing their homeland again, without hope of living out a fruitful life.

When the poor wretches saw the terrible damage above deck, the stumps of the masts, the shattered bulwarks, the missing boats, they were overwhelmed with despair. The women began uttering cries of terror, all except one, Scaggs noted, who stood out from the rest.

His eyes briefly paused on the female convict, who was nearly as tall as most of the men. The legs showing beneath her skirt were long and smooth. Her narrow waist was shadowed by a nicely shaped bosom that spilled over the top of her blouse. Her clothes appeared neat and clean, and her waist-length yellow hair had a brushed luster to it, unlike that of the other women, whose hair was unkept and stringy. She stood poised, her fear masked by a show of defiance as she stared back at Scaggs through eyes as blue as an alpine lake.

This was the first time Scaggs had noticed her, and he idly wondered why he hadn’t been more observant. He refocused his wandering thoughts on the emergency at hand and addressed the convicts.

“Our situation is not promising,” Scaggs began. “In all honesty I must tell you the ship is doomed, and with the sea’s destruction of our boats, we cannot abandon her.”

His words were greeted with a mixed reaction. Lieutenant Sheppard’s infantrymen stood silent and motionless, while many of the convicts began to wail and moan piteously. Expecting to see the ship go to pieces within moments, several of the convicts fell to their knees and begged the heavens for salvation.

Turning a deaf ear to the doleful cries, Scaggs continued his address. “With the help of a merciful God, I will attempt to save every soul on this ship. I intend to build a raft of sufficient size to carry everyone on board until we are saved by a passing ship or drift ashore on the Australian mainland. We’ll load ample provisions of food and water, enough to last us for twenty days.”

“If you don’t mind me asking, Captain, how soon do you reckon before we’d be picked up?”

The question came from a huge man with a contemptuous expression who stood head and shoulders above the rest. Unlike his companions he was fashionably dressed, with every hair on his head fastidiously in place.

Before answering, Scaggs turned to Lieutenant Sheppard. “Who’s that dandy?”

Sheppard leaned toward the captain. “Name is Jess Dorsett.”

Scaggs’ eyebrows raised. “Jess Dorsett the highwayman?”

The lieutenant nodded. “The same. Made a fortune, he did, before the Queen’s men caught up with him. The only one of this motley mob who can read and write.”

Scaggs immediately realized that the highwayman might prove valuable if the situation on the raft turned menacing. The possibility of mutiny was very real. “I can only offer you all a chance at life, Mr. Dorsett. Beyond that I promise nothing.”

“So what do you expect of me and my degenerate friends here?”

“I expect every able-bodied man to help build the raft. Any of you who refuse or shirk will be left behind on the ship.”

“Hear that, boys?” Dorsett shouted to the assembled convicts. “Work or you die.” He turned back to Scaggs. “None of us are sailors. You’ll have to tell us how to go about it.”

Scaggs gestured toward his first officer. “I have charged Mr. Ramsey with drawing up plans and framing the raft. A work party drawn from those of my crew not required to keep us afloat will direct the construction.”

At six feet four, Jess Dorsett seemed a giant when standing among the other convicts. The shoulders beneath the expensive velvet coat stretched broad and powerful. His copper-red hair was long and hung loose over the collar of the coat. His head was large nosed, with high cheekbones and a heavy jaw. Despite two months of hardship, locked in the ship’s hold, he looked as though he’d just stepped out of a London drawing room.

Before they turned from each other, Dorsett and Scaggs briefly exchanged glances. First Officer Ramsey caught the intensity. The tiger and the lion, he thought pensively. He wondered who would be left standing at the end of their ordeal.

Fortunately, the sea had turned calm, since the raft was to be built in the water. The construction began with the materials being thrown overboard. The main framework was made up from the remains of the masts, lashed together with a strong rope. Casks of wine along with barrels of flour meant for the taverns and grocery stores of Sydney were emptied and tied within the masts for added buoyancy. Heavy planking was nailed across the top for a deck and then surrounded by a waist-high railing. Two spare topmasts were erected fore and aft and fitted with sails, shrouds and stays. When completed the raft measured eighty feet in length by forty feet wide, and though it looked quite large, by the time the provisions were loaded on board, it was a tight squeeze to pack in 192 convicts, 11 soldiers and the ship’s crew, which numbered 28, including Bully Scaggs, for a total of 231. At what passed for the stern, a rudimentary rudder was attached to a makeshift tiller behind the aft mast.

Wooden kegs containing water, lime juice, brined beef and pork, as well as cheese, and several pots of rice and peas cooked in the ship’s galley, were lowered on board between the masts and tied down under a large sheet of canvas that was spread over two thirds of the raft as an awning to ward off the burning rays of the sun.

The departure was blessed by clear skies and a sea as smooth as a millpond. The soldiers were disembarked first, carrying their muskets and sabers. Then came the convicts, who were all too happy to escape sinking with the ship, now dangerously down by the bow. The ship’s ladder was inadequate to support them all, so most came over the side, dangling from ropes. Several jumped or fell into the water and were recovered by the soldiers. The badly injured were lowered by slings. Surprisingly, the exodus was carried off without incident. In two hours, all 203 were safely stationed on the raft in positions assigned by Scaggs.

The crew came next, Captain Scaggs the last man to leave the steeply slanting deck. He dropped a box containing two pistols, the ship’s log, a chronometer, compass and a sextant into the arms of First Officer Ramsey. Scaggs had taken a position fix before dropping over the side and had told no one, not even Ramsey, that the storm had blown the Gladiator far off the normal shipping routes. They were drifting in a dead area of the Tasman Sea, three hundred miles from the nearest Australian shore, and what was worse, the current was carrying them even farther into nothingness where no ships sailed. He consulted his charts and determined their only hope was to take advantage of the adverse current and winds and sail east toward New Zealand.

Soon after settling in, everyone in their place on the crowded deck, the raft’s passengers found to their dismay that there was only enough space for forty bodies to lie down at any one time. It was obvious to the seamen from the ship that their lives were in great jeopardy; the planked deck of the raft was only four inches above the water. If confronted with a rough sea, the raft and its unfortunate passengers would be immersed.

Scaggs hung the compass on the mast forward of the tiller. “Set sail, Mr. Ramsey. Steer a heading of one-fifteen degrees east-southeast.”

“Aye, Captain. We’ll not try for Australia, then?”

“Our best hope is the west coast of New Zealand.”

“How far do you make it?”

“Six hundred miles,” Scaggs answered as if a sandy beach lay just over the horizon.

Ramsey frowned and stared around the crowded raft. His eyes fell on a group of convicts who were in hushed conversation. Finally, he spoke in a tone heavy with gloom. “I don’t believe any of us God-fearin’ men will see deliverance while we’re surrounded by this lot of scum.”

The sea remained calm for the next five days. The raft’s passengers settled into a routine of disciplined rationing. The cruel sun beat down relentlessly, turning the raft into a fiery hell. There was a desperate longing to drop into the water and cool their bodies, but already the sharks were gathering in anticipation of an easy meal. The seamen threw buckets of saltwater on the canvas awning, but it only served to heighten the humidity beneath.

Already the mood on the raft had begun to swing from melancholy to treachery. Men who had endured two months of confinement in the dark hold of the Gladiator now became troubled without the security of the ship’s hull and with being encompassed by nothingness. The convicts began to regard the sailors and the soldiers with ferocious looks and mutterings that did not go unnoticed by Scaggs. He ordered Lieutenant Sheppard to have his men keep their muskets loaded and primed at all times.

Jess Dorsett studied the tall woman with the golden hair. She was sitting alone beside the forward mast. There was an aura of tough passivity about her, a manner of overlooking the hardships without expectations. She appeared not to notice the other female convicts, seldom conversing, choosing to remain aloof and quiet. She was, Dorsett decided, a woman of values.

He snaked toward her through the bodies packed on board the raft until he was stopped by the hard gaze of a soldier who motioned him back with a musket. Dorsett was a patient man and waited until the guards changed shifts. The replacement promptly began leering at the women, who quickly taunted him. Dorsett took advantage of the diversion to move until he was at the imaginary boundary line dividing the men from the women. The blond woman did not notice, her blue eyes were fixed on something only she could see in the distance.

“Looking for England?” he asked, smiling.

She turned and stared at him as if making up her mind whether to grace him with an answer. “A small village in Cornwall.”

“Where you were arrested?”

“No, that was in Falmouth.”

“For attempting to murder Queen Victoria?”

Her eyes sparkled and she laughed. “Stealing a blanket, actually.”

“You must have been cold.”

She became serious. “It was for my father. He was dying from the lung disease.”

“I’m sorry.”

“You’re the highwayman.”

“I was until my horse broke her leg and the Queen’s men ran me down.”

“And your name is Jess Dorsett.” He was pleased that she knew who he was and wondered if she had inquired of him. “And you are …?”

“Betsy Fletcher,” she answered without hesitation.

“Betsy,” Dorsett said with a flourish, “consider me your protector.”

“I need no fancy highwayman,” she said smartly. “I can fend for myself.”

He motioned around the horde jammed on the raft. “You may well need a pair of strong hands before we see hard ground again.”

“Why should I put my faith in a man who never got his hands dirty?”

He stared into her eyes. “I may have robbed a few coaches in my time, but next to the good Captain Scaggs, I’m most likely the only man you can trust not to take advantage of a woman.”

Betsy Fletcher turned and pointed at some evil-looking clouds scudding in their direction before a freshening breeze. “Tell me, Mr. Dorsett, how are you going to protect me from that?”

…

“We’re in for it now, Captain,” said Ramsey. “We’d better take down the sails.”

Scaggs nodded grimly. “Cut short lengths of rope from the keg of spare cordage and pass them around. Tell the poor devils to fasten themselves to the raft to resist the turbulence.”

The sea began to heap up uncomfortably, and the raft lurched and rolled as the waves began to sweep over the huddled mass of bodies, each passenger clutching their individual length of rope for dear life, the smart ones having tied themselves to the planks. The storm was not half as strong as the typhoon that did in the Gladiator, but it soon became impossible to tell where the raft began and the sea left off. The waves rose ever higher as the whitecaps blew off their crests. Some tried to stand to get their heads above water, but the raft was pitching and rolling savagely. They fell back on the planking almost immediately.

Dorsett used both his and Betsy’s ropes to fasten her to the mast. Then he wrapped himself in the shroud lines and used his body to shield her from the force of the waves. As if to add insult to injury, rain squalls pelted them with the force of stones cast by devils. The disorderly seas struck from every direction.

The only sound that came above the fury of the storm was Scaggs’ vehement cursing as he shouted orders to his crew to add more lines to secure the mound of provisions. The seamen struggled to lash down the crates and kegs, but a mountainous wave reared up at that moment and crashed down onto the raft and pushed it deep under the water. For the better part of a minute there was no one on that pathetic craft who didn’t believe they were about to die.

Scaggs held his breath and closed his eyes and swore without opening his mouth. The weight of the water felt as though it was crushing the life out of him. For what seemed an eternity the raft sluggishly rose through a swirling mass of foam into the wind again. Those who hadn’t been swept into the sea inhaled deeply and coughed out the saltwater.

The captain looked around the raft and was appalled. The entire mass of provisions had been carried away and had disappeared as if they had never been loaded aboard. What was even more horrendous was that the bulk of the crates and kegs had carved an avenue through the pack of convicts, maiming and thrusting them from the raft with the force of an avalanche. Their pathetic cries for help went unanswered. The savage sea made any attempt at rescue impossible, and the lucky ones could only mourn the bitter death of their recent companions.

The raft and its suffering passengers endured the storm through the night, pounded by the wash that constantly rolled over them. By the following morning the sea had begun to ease off, and the wind dwindled to a light southerly breeze. But they still kept an eye out for the occasional renegade wave that lurked out of sight before sweeping in and catching the half-drowned survivors off guard.

When Scaggs was finally able to stand and appraise the total extent of the damage, he was shocked to find that not one keg of food or water had been spared from the violence of the sea. Another disaster. The masts were reduced to a few shreds of canvas. He ordered Ramsey and Sheppard to take a count of the missing. The number came to twenty-seven.

Sheppard shook his head sadly as he stared at the survivors. “Poor beggars. They look like drowned rats.”

“Have the crew spread what’s left of the sails and catch as much rainwater as possible before the squall stops,” Scaggs ordered Ramsey.

“We no longer have containers to store it,” Ramsey said solemnly. “And what will we use for sails?”

“After everybody drinks their fill, we’ll repair what we can of the canvas and continue on our east-southeast heading.”

As life reemerged on the raft, Dorsett untied himself from the mast shrouds and gripped Betsy by the shoulders. “Are you harmed?” he asked attentively.

She peered at him through long strands of hair that were plastered against her face. “I won’t be attending no royal ball looking like a drenched cat. Soaked as I am, I’m glad to be alive.”

“It was a bad night,” he said grimly, “and I fear it won’t be the last.”

Even as Dorsett comforted her, the sun returned with a vengeance. Without the awning, torn away by the onslaught of the wind and waves, there was no protection from the day’s heat. The torment of hunger and thirst soon followed. Every morsel of food that could be found among the planks was quickly eaten. The little rainfall caught by the torn canvas sails was soon gone.

When their tattered remains were raised again, the sails had little effect and proved almost worthless for moving the raft. If the wind came from astern, the vessel was manageable. But attempting to tack only served to twist the raft into an uncontrollable position crosswise with its beam to the wind. The inability to command the direction of the raft only added to Scaggs’ mounting frustrations. Having saved his precious navigational instruments by clutching them to his breast during the worst of the deluge, he now took a fix on the raft’s position.

“Any nearer to land, Captain?” asked Ramsey.

“I’m afraid not,” Scaggs said gravely. “The storm drove us north and west. We’re farther away from New Zealand than we were at this time two days ago.”

“We won’t last long in the Southern Hemisphere in the dead of summer without fresh water.”

Scaggs gestured toward a pair of fins cutting the water fifty feet from the raft. “If we don’t sight a boat within four days, Mr. Ramsey, I fear the sharks will have themselves a sumptuous banquet.”

The sharks did not have long to wait. The second day after the storm, the bodies of those who succumbed from injuries sustained during the raging seas were slipped over the side and quickly disappeared in a disturbance of bloody foam. One monster seemed particularly ravenous. Scaggs recognized it as a great white, feared as the sea’s greediest murder machine. He estimated its length to be somewhere between twenty-two and twenty-four feet.

The horror was only beginning. Dorsett was the first to have a premonition of the atrocities that the poor wretches on the raft would inflict upon themselves.

“They’re up to something,” he said to Betsy. “I don’t like the way they’re staring at the women.”

“Who are you talking about?” she asked through parched lips. She had covered her face with a tattered scarf, but her bare arms and her legs below the skirt were already burned and blistered from the sun.

“That scurvy lot of smugglers at the stern of the raft, led by the murderin’ Welshman, Jake Huggins. He’d as soon slit your gullet as give you the time of day. I’ll wager they’re planning a mutiny.”

Betsy stared vacantly around the bodies sprawled on the raft. “Why would they want to take command of this?”

“I mean to find out,” said Dorsett as he began making his way over the convicts slouched about the damp planking, oblivious to everything around them while suffering from a burning thirst. He moved awkwardly, annoyed at how stiff his joints had become with no exercise except holding onto ropes. He was one of the few who dared approach the conspirators, and he muscled his way through Huggins’ henchmen. They ignored him as they muttered to themselves in low tones and cast fierce looks at Sheppard and his infantrymen.

“What brings you nosin’ around, Dorsett?” grunted Huggins.

The smuggler was short and squat with a barrel chest, long matted sandy hair, an extremely large flattened nose and an enormous mouth with missing and blackened teeth, which combined to give him a hideous leer.

“I figured you could use a good man to help you take over the raft.”

“You want to get in on the spoils and live a while longer, do you?”

“I see no spoils that can prolong our suffering,” Dorsett said indifferently.

Huggins laughed, showing his rotting teeth. “The women, you fool

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...