- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

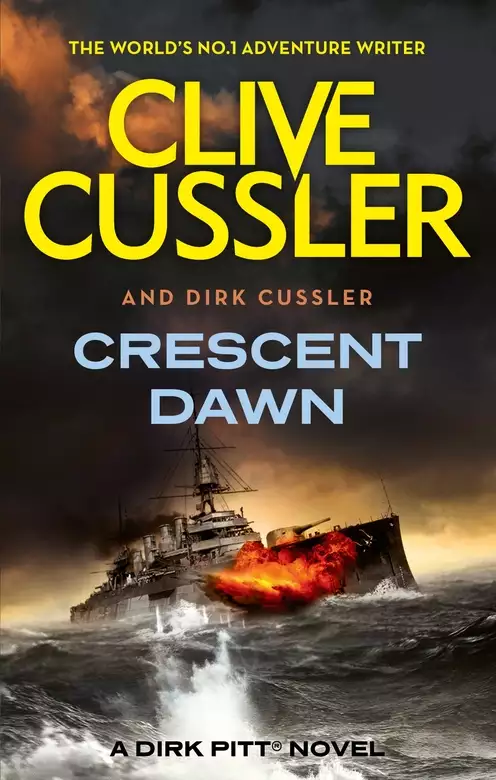

Dirk Pitt returns in the extraordinary new novel from the #1 New York Times bestselling author.

In A.D. 327, a Roman galley barely escapes a pirate attack with its extraordinary cargo. In 1916, a British warship mysteriously explodes in the middle of the North Sea. In the present day, a cluster of important mosques in Turkey and Egypt are wracked by explosions. Does anything tie them together?

NUMA director Dirk Pitt is about to find out, as Roman artifacts discovered in Turkey and Israel unnervingly connect to the rise of a fundamentalist movement determined to restore the glory of the Ottoman Empire, and to the existence of a mysterious "manifest," lost long ago, which if discovered again . . . just may change the history of the world as we know it.

Release date: November 16, 2010

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 640

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Crescent Dawn

Clive Cussler

CAIRO, EGYPT

THE NOONDAY SUN BURNED THROUGH THE dense layer of dust and pollutants that hung over the ancient city like a soiled blanket. With the temperature well over the century mark, few people lingered about the hot stones that paved the central court of al-Azhar Mosque.

Situated in eastern Cairo some two miles from the Nile, al-Azhar stood as one of the city’s most historic structures. Originally constructed in A.D. 970 by Fatimid conquerors, the mosque was rebuilt and expanded through the centuries, ultimately attaining status as Islam’s fifth most important mosque. Elaborate stone carvings, towering minarets, and onion-domed spires vied for the eye’s attention, reflecting a thousand years of artistry. Amid its fortresslike stone walls, the centerpiece of the complex was a wide rectangular court surrounded by rising arcades on every side.

In the shade of an arcade portico, a slight man in baggy trousers and a loose-fitting shirt wiped clean a pair of tinted glasses, then surveyed the courtyard. In the heat of the day, only a small number of youths were about, studying the architecture or walking in silent meditation. They were students from the adjacent al-Azhar University, a preeminent institution for Islamic learning in the Middle East. The man touched a thick beard that covered his own youthful face, then lifted a worn backpack to his shoulder. With a white cotton keffiyeh wrapped about his head, he easily passed as just another theology student.

Stepping into the sunlight, he trekked across the court toward the southeast arcade. The façade above the keel-shaped arches featured a series of ornate roundels and niches cut into the stucco, which he noticed had become favored roosting spots for some local pigeons. He walked toward a protruding central arch topped by a high rectangular panel, which signified the entrance to the prayer hall.

The call to midday salat, or prayer, had occurred nearly an hour earlier, leaving the expansive prayer hall nearly empty. Outside the foyer, a small group of students sat cross-legged on the ground, listening to a university instructor lecture on the Qur’an. Skirting around the group, the man approached the hall entry. There he met a bearded man in a white robe, who eyed him sternly. The visitor removed his shoes and quietly offered a blessing to Muhammad, then proceeded in with a nod from the doorman.

The prayer hall was an open expanse of red carpet punctuated by dozens of alabaster pillars that rose to a beamed ceiling. As in most mosques, there were no pews or ornate altars to provide orientation. Cupola-shaped patterns in the carpet, outlining individual positions of prayer, pointed toward the head of the hall. Noting that the bearded doorman no longer paid him any attention, the man made his way quickly along the pillars.

Approaching several men kneeling in prayer, he spotted the mihrab across the hall. An often unassuming niche carved into a mosque’s wall, it indicated the direction of Mecca. Al-Azhar’s mihrab was cut of smooth stone and arched with a wavy black-and-ivory stone inlay that had a nearly modern design.

Moving to a pillar closest to the mihrab, the man slipped off his backpack, then lay prone on the carpet in prayer. After several minutes, he gently pushed his pack to the side until it wedged against the base of the pillar. Spotting a pair of students walking in the direction of the entrance, he rose and followed them to the foyer, where he retrieved his shoes. Passing the bearded elder, he muttered, “Allahu Akbar,” then quickly stepped into the courtyard.

He pretended to briefly admire a rosette in the façade, then quickly made his way to the Barber’s Gate, which led out of the mosque compound. A few blocks away, he climbed into a small rental car parked on the street and drove in the direction of the Nile. Passing through a dingy industrial neighborhood, he turned onto the lot of a crumbling old brickyard and pulled behind its abandoned loading dock. There he pulled off his loose trousers and shirt, revealing a pair of jeans and silk blouse underneath. The eyeglasses were removed, along with a wig, and then the fake beard. The male Muslim student was no more, replaced by an attractive, olive-skinned woman with hard dark eyes and stylishly layered short black hair. Ditching her disguise in a rusty garbage bin, she hopped back into the car and rejoined Cairo’s sluggish traffic, crawling away from the Nile to the Cairo International Airport on the northeast side of town.

She was standing in line at the check-in counter when the backpack exploded. A small white cloud rose over al-Azhar Mosque as the prayer hall roof was blown off and the mihrab shattered into a pile of rubble. Though the explosion had been timed to detonate between daily prayers, several students and mosque attendants were killed and dozens more injured.

After the initial shock subsided, the Cairo Muslim community was outraged. Israel was blamed first, then other Western nations were targeted when no one claimed responsibility for the blast. In a few weeks, the prayer hall would be repaired and a new mihrab quickly installed. But to Muslims across Egypt and around the world, the anger at the assault on such a sacred site lasted much longer. Few could have recognized, however, that the attack was only the first salvo in a strategic ploy that would attempt to transform the very dominance of the entire region.

“TAKE THE KNIFE AND CUT IT FREE.”

An angry scowl covered the Greek fisherman’s face as he handed his son a rusty serrated knife. The teenage boy stripped down to his shorts, then leaped off the side of the boat, the knife held firmly in one hand.

It had been nearly two hours since the trawler’s fishing nets had first snagged on the bottom, much to the surprise of the old Greek, who had safely dragged these waters many times before. He ran his boat in every direction, hoping to work the nets free, cursing loudly as his frustration mounted. Try as he might, the nets held firm. It would be a costly loss to cut away a portion of his nets, but the fisherman grudgingly accepted the occupational hazard and sent his boy over the side.

Though windswept on the surface, the waters of the eastern Aegean Sea were warm and clear, and at thirty feet down the boy could faintly see the bottom. But it was still well beyond his ability to free-dive, so he halted his descent and attacked the dangling nets with his knife. It took several dives before the last strand was cut free and the boy yanked to the surface with the damaged nets, exhausted and out of breath. Still cursing over his loss, the fisherman turned the boat west and putted off toward Chios, a Greek island close to the Turkish mainland, which rose from the azure waters a short distance away.

A quarter mile farther out to sea, a man studied the fisherman’s plight with curiosity. His frame was tall and lean yet robust, his skin deeply tanned from years in the sun. He lowered an old-fashioned brass telescope from his brow, exposing a pair of sea-green eyes that flickered with intelligence. They were reflective eyes, hardened by adversity and numerous brushes with death, yet they softened easily with humor. He rubbed his hand through thick ebony hair flecked with gray, then he stepped onto the bridge of the research vessel Aegean Explorer.

“Rudi, we’ve surveyed a good chunk of the bottom between here and Chios, haven’t we?” he asked.

A diminutive man with horn-rimmed glasses looked up from a computer station and nodded his head.

“Yes, our last grid ran within a mile of the eastern shore. With the Greek island situated less than five miles from Turkey, I don’t even know whose waters we’re in. We had about ninety percent of the grid complete when the AUV’s rear sensor blew a seal and flooded with salt water. We’ll be down at least two more hours while our technicians repair the damage.”

The AUV, or autonomous underwater vehicle, was a torpedo-shaped robot packed with sensing equipment that was dropped over the side of the research ship. Self-propelled and preprogrammed with a designated survey path, the AUV would cruise above the seafloor collecting data that was periodically relayed back to the surface ship.

Rudi Gunn resumed tapping at the keyboard. Dressed as he was in a tattered T-shirt and plaid shorts, nobody would have guessed he was the Deputy Director for the National Underwater and Marine Agency, the prominent government organization responsible for the scientific study of the world’s oceans. Gunn was normally confined to NUMA’s Washington headquarters rather than stationed aboard one of the turquoise-colored research vessels that the agency used to gather information on marine life, ocean currents, and environmental pollution. An adept administrator, he relished escaping the hubris of the nation’s capital and getting his hands dirty in the field, especially when his boss had escaped likewise.

“What sort of bottom contours have we seen in the shallows around here?”

“Typical of the local islands. A sloping shelf extends offshore a short distance before abruptly plunging to thousand-foot depths. We’re in about a hundred and twenty feet of water here. As I recall, this area has a fairly sandy bottom, with few obstructions.”

“That’s what I thought,” the man replied, a sparkle growing in his eye.

Gunn caught the look and said, “I detect a devious plot in the boss’s head.”

Dirk Pitt laughed. As the Director of NUMA, he had led dozens of underwater explorations, with remarkable results. From raising the Titanic to discovering the ships of the lost Franklin Expedition in the Arctic, Pitt had an uncanny knack for solving the mysteries of the deep. A quietly confident man with an insatiable curiosity, he’d been enamored of the sea from an early age. The lure never waned, and it drew him out of NUMA’s Washington headquarters on a regular basis.

“It’s a known fact,” he said cheerily, “that most inshore shipwrecks are found by the nets of local fishermen.”

“Shipwrecks?” Gunn replied. “As I recall, our invitation from the Turkish government was to locate and study the impact of algae blooms reported along their coastal waters. There was no mention of any wreck searches.”

“I only take them as they come.” Pitt smiled.

“Well, we are out of commission for the moment. Do you want to drop the ROV over the side?”

“No, the nets of our neighborhood fisherman are snagged well within diving range.”

Gunn looked at his watch. “I thought you were leaving in two hours to spend the weekend in Istanbul with your wife.”

“More than enough time,” Pitt said with a grin, “for a quick dive on the way to the airport.”

“Then I guess this means,” Gunn replied with a resigned shake of the head, “that I gotta go wake up Al.”

TWENTY MINUTES LATER, Pitt tossed an overnight bag into a Zodiac that bobbed alongside the Aegean Explorer, then climbed a portable ladder down into the boat. As he took his seat, a short barrel-chested man at the stern twisted the throttle on a small outboard motor, and the rubber boat leaped away from the ship.

“Which way to the bottom?” Al Giordino shouted, the cobwebs from an afternoon siesta slowly clearing from his dark brown eyes.

Pitt had taken a visual bearing using several landmarks on the neighboring island. Guiding Giordino inshore on a decided angle, they motored just a short distance before Pitt ordered the engine cut. He then threw a small anchor over the bow, tying it off when the line went slack.

“Just over a hundred feet,” he remarked, eyeing a red stripe on the line that was visible underwater.

“And just what do you expect to find down below?”

“Anything from a pile of rocks to the Britannic,” Pitt replied, referring to a sister ship of the Titanic that was sunk by a mine in the Mediterranean during World War I.

“My money’s on the rocks,” Giordino replied, slipping into a blue wet suit whose seams were tested by his brawny shoulders and biceps.

Deep down, Giordino knew there would be something more interesting than an outcropping of rocks at the bottom. He had too much history with Pitt to question his friend’s apparent sixth sense when it came to underwater mysteries. The two had been childhood friends, in Southern California, where they’d learned to dive together off Laguna Beach. While serving in the Air Force, they’d both taken a temporary assignment at a fledgling new federal department tasked with studying the oceans. Scores of projects and adventures later, Pitt now headed up the vastly expanded agency called NUMA, while Giordino worked alongside him as his Director of Underwater Technology.

“Let’s try an elongated circle search off the anchor line,” Pitt suggested, as they buckled on their air tanks. “My bearing puts the net snag slightly inshore of our present position.”

Giordino nodded, then stuffed a regulator into his mouth and slipped backward off the Zodiac and into the water. Pitt splashed in a second later, and the two men followed the anchor line to the bottom.

The blue waters of the Aegean Sea were remarkably clear, and Pitt had no trouble seeing fifty feet or more. As they approached the darkened bottom, he noted with some satisfaction that the seafloor was a combination of flat gravel and sand. Gunn’s assessment was correct. The area appeared to be naturally free of obstructions.

The two men spread apart a dozen feet above the seafloor and swam a lazy arc seaward around the anchor line. A small school of sea bass cruised by, eyeing the divers suspiciously before darting away to deeper water. As they angled around toward Chios, Pitt noticed Giordino waving at him. Thrusting his legs in a strong scissors kick, Pitt swam closer, finding his partner pointing to a large shape ahead of them.

It was a towering brown shadow that seemed to waver in the thin light. It reminded Pitt of a windblown tree, its leafy branches sprouting skyward. Swimming closer, he saw that it was no tree but the remnants of the fisherman’s nets drifting lazily in the current.

Leery of entanglement, the two divers moved cautiously, positioning themselves up current as they approached. The nets were caught on a single point, protruding just above the seafloor. Pitt could see a faint trench scratched across the gravel-and-sand bottom, ending in an upright spar tangled with the nets. Kicking closer to the obstruction, he could see that it was a corroded T-shaped iron anchor about five feet in length. The anchor was tilted on its side, with one fluke pointing toward the surface, the fisherman’s nets hopelessly ensnarled around it, while the other fluke was embedded in the seafloor. Pitt reached down and fanned away around the base, revealing that the buried fluke was wedged between a thick beam of wood and a smaller cross frame. Pitt had explored enough shipwrecks to recognize the thick beam as a ship’s keel.

He turned away from the nets and eyed the wide, shallow trench that had recently been scratched across the bottom. Giordino was already hovering over it, tracking it to its origin. Like Pitt, he had surmised what happened. The fishing nets had snagged the anchor at one end of the wreck and dragged it along the keel line until it had caught a cross frame and held firm. The action had unwittingly exposed a large portion of an aged shipwreck.

Pitt swam toward Giordino, who was fanning sand from a linear protrusion. Clearing the protective sediment revealed several pieces of cross frame beneath the keel. Giordino gazed into Pitt’s dive mask with bright eyes and shook his head. Pitt’s underwater sense had sniffed out a shipwreck, and an old one at that.

Uncovering bits and pieces as they swept the perimeter, they could tell that the ship was about fifty feet long, and its upper deck had long since eroded away. Most of the vessel had in fact disappeared, with just a few sections of the hull surviving intact. Yet at the stern, portions of several small compartments were evident beneath soft sand. Ceramic dishes, tile, and fragments of unglazed pottery were visible throughout, although the ship’s actual cargo was not apparent.

With their bottom time beginning to run low, the two divers returned to the stern and scooped away sections of gravel and sand, searching for anything that might help identify the wreck. Poking through an area of loose timbers, Giordino’s fingers brushed upon a flat object under the sand and he dug down to find a small metal box. Holding it up to his mask, he could see a pin-type locking mechanism was encrusted to the front, though the shackle was mostly corroded away. Carefully wrapping it in a dive bag, he checked his watch, then swam over to Pitt and signaled that he was surfacing.

Pitt had uncovered a small row of clay pots, which he left undisturbed as Giordino approached. He was turning to follow Giordino to the surface when a small glint in the sand caught his eye. It came from opposite the pots, where his fins had brushed up some bottom sediment. Pitt swam around and fanned away more sand, exposing a flat section of ceramic. Though it was caked with concretions, he could see that the design featured an elaborate floral motif. Digging his fingers into the sand, he grasped the edges of a rectangular box and pulled it free.

The ceramic container was about twice the size of a cigar box, its flat sides emblazoned with a blue-and-white design that matched the lid. The box felt heavy for its size, and Pitt carefully tucked it under one arm before kicking toward the surface.

A steady afternoon breeze was building from the northwest, pestering the water with whitecaps. Giordino was already aboard the Zodiac, yanking up the anchor, when Pitt appeared. He kicked over to the rubber boat and handed Giordino the box, then climbed aboard and stripped off his dive gear.

“Guess you owe that fisherman a bottle of ouzo,” Giordino said, starting up the outboard motor.

“He certainly put us on an interesting wreck,” Pitt replied, drying his face with a towel.

“Not an amphora-carrying Bronze Age wreck, but she still looked pretty old.”

“Possibly medieval,” Pitt guessed. “A mere child, by Mediterranean wreck standards. Let’s get to shore and see what we’ve got.”

Giordino gunned the motor, driving the Zodiac up on its keel, then turned toward the nearby island. Chios itself was two miles away, but it was another three miles up the coast before they entered the small bay of a sleepy fishing village called Vokaria. They tied up at a weather-beaten pier that looked like it had been built during the Age of Sail. Giordino then threw a towel down onto the dock, and Pitt laid out the two artifacts.

Both items were covered in a layer of sandy concretion, built up over centuries underwater. Pitt located a freshwater hose nearby and carefully scrubbed away some of the layered muck on the ceramic box. Free of grime and held aloft under the sunlight, it dazzled the eye. An intricate floral pattern of dark blue, purple, and turquoise burst against a bright white background.

“Looks a bit Moroccan,” Giordino said. “Can you pop the top off?”

Pitt carefully worked his fingers under the overhanging lid. Finding a light resistance, he gently forced it free. Inside, the box was filled with dirty water, along with an oblong object that glittered faintly through the murk. Pitt carefully tilted the box to one side, draining it.

He reached in and pulled out a semicircular object that was heavily encrusted. To his shock, he could see that it was a crown. Pitt held it up gingerly, feeling the heavy weight of its solid-gold construction, the metal gleaming from portions that were free of sediment.

“Will you look at that?” Giordino marveled. “Looks like something straight out of King Arthur.”

“Or perhaps Ali Baba,” Pitt replied, looking at the ceramic box.

“That shipwreck must be no ordinary merchant runner. You think it might be some sort of royal vessel?”

“Anything is possible,” Pitt replied. “It would seem somebody important was traveling aboard.”

Giordino took hold of the crown and placed it on his head at a rakish angle.

“King Al, at your service,” he said, with a wave of his arm. “Bet I could attract a fine local lady wearing this.”

“Along with some men in white jackets,” Pitt scoffed. “Let’s take a look at your lockbox.”

Giordino set the crown back into the ceramic case, then picked up the small iron box. As he did, the corroded padlock slipped off, dropping to the towel.

“Security ain’t what it used to be,” he muttered, setting the box back down. Emulating Pitt, he worked the edges of the lid with his fingers, prying the top off with a pop. Only a small amount of seawater sloshed about inside, for the container was filled nearly to the rim with coins.

“Talk about hitting the jackpot.” He grinned. “Looks like we may be in for an early retirement.”

“Thank you, no. I’d rather not spend my retirement years in a Turkish prison,” Pitt replied.

The coins were made of silver and badly corroded, several of them melded together. Pitt reached to the bottom of the pile and pulled out one that glimmered, a lone gold coin that hadn’t suffered the effects of corrosion. He held it up to his eye, noting an irregular stamp, indicative of hammered coinage. Swirling Arabic lettering was partially visible on both sides, surrounded by a serrated ring. Pitt could only guess as to the age and origin of the coin. The two men curiously examined the other coins, which in their condition revealed few markings.

“Based on our limited evidence, I’d guess we have an Ottoman wreck of some sort on our hands,” Pitt declared. “The coins don’t look Byzantine, which means fifteenth century or later.”

“Somebody should be able to date those accurately.”

“The coins were a lucky find,” Pitt agreed.

“I say fund the project another month and avoid going back to Washington.”

A battered Toyota pickup truck approached along the dock, squealing to a halt in front of the men. A smiling youth with big ears climbed out of the truck.

“A ride to the airport?” he asked haltingly.

“Yes, that’s me,” Pitt said, retrieving his overnight bag from the Zodiac.

“What about our goodies?” Giordino asked, carefully wrapping the items in the towel before the driver could examine them.

“To Istanbul with me, I’m afraid. I know the Director of Maritime Studies at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. He’ll find a good home for the artifacts and hopefully tell us what we found.”

“I guess that means no wild night out on Chios for King Al,” Giordino said, passing the towel to Pitt.

Pitt glanced at the sleepy village ringing the harbor, then climbed into the idling truck.

“To be honest,” he said as the driver began pulling away, “I’m not sure Chios is ready for King Al.”

THE COMMUTER PLANE TOUCHED DOWN AT Atatürk International Airport in Istanbul just before dark. Scurrying around a mass of commercial jumbo jets like a mosquito in a beehive, the small plane pulled into an empty terminal slot and bumped to a halt.

Pitt was one of the last passengers off the plane and had barely stepped into the tiled terminal when he was mauled by a tall attractive woman with cinnamon-colored hair.

“You were supposed to beat me here,” Loren Smith said, pulling away after a deep embrace. “I was afraid you weren’t going to come at all.” Her violet eyes beamed with relief as she gazed at her husband.

Pitt crooked an arm around her waist and gave her a long kiss. “A tire problem on the plane delayed our departure. Have you been waiting long?”

“Less than an hour.” She crumpled her nose and licked her lips. “You taste salty.”

“Al and I found a shipwreck on the way to the airport.”

“I should have guessed,” she said, then gave him a scolding look. “I thought you told me flying and diving didn’t mix.”

“They don’t. But that puddle jumper I flew in on barely cleared a thousand feet, so I’m plenty safe.”

“You get the bends while we’re in Istanbul, and I’ll kill you,” she said, holding him tight. “Is the shipwreck anything interesting?”

“It appears to be.”

He held up his overnight bag with the artifacts wrapped inside. “We retrieved a couple of artifacts that should be revealing. I invited Dr. Rey Ruppé of the Istanbul Archaeology Museum to join us for dinner tonight, in hopes that he can shed some further light.”

Loren stood on her toes and looked into Pitt’s green eyes, her brow wrinkled.

“It’s a good thing I knew when I married you that you’d always keep the sea as a mistress,” she said.

“Fortunately,” he replied with a grin while holding her close, “I have a heart big enough for the both of you.”

Grabbing her hand, they waded through the terminal crowd and collected his baggage, then caught a taxi to a hotel in Istanbul’s central historic district of Sultanahmet. After a quick shower and change, they hopped another cab for a short ride to a quiet residential area a dozen blocks away.

“Balikçi Sabahattin,” the cabdriver announced.

Pitt helped Loren out onto a quaint cobblestone lane. On the opposite side of the street was the restaurant, housed in a picturesque wood-frame house built in the 1920s. The couple waded past some tables outside to reach the front door and entered an elegant foyer. A thickset man with thinning hair and a jovial smile stepped up and shoved out a hand in greeting.

“Dirk, glad you could find the place,” he said, crushing Pitt’s hand in a vise grip. “Welcome to Istanbul.”

“Thanks, Rey, it’s good to see you again. I’d like you to meet my wife, Loren.”

“A pleasure,” Ruppé replied graciously, shaking Loren’s hand with less vigor. “I hope you can forgive an old shovel jockey’s intrusion on dinner tonight. I’m off to Rome in the morning for an archaeology conference, so this was the only opportunity I had to discuss your husband’s underwater discovery.”

“It’s no intrusion at all. I’m always fascinated by what Dirk pulls off the seafloor,” she said with a laugh. “Plus, you have obviously led us to a lovely dining spot.”

“One of my favorite seafood restaurants in Istanbul,” Ruppé replied.

A hostess appeared and escorted them down a hallway to one of several dining rooms fitted into the former house. They took their seats at a linen-covered table aside a large window that overlooked the back garden.

“Perhaps you can recommend some regional favorites, Dr. Ruppé,” Loren said. “It’s my first visit to Turkey.”

“Please, call me Rey. When in Turkey, you can never go wrong with fish. Both the turbot and sea bass are excellent here. Of course, I can never seem to eat my fill of kebobs, either.” He grinned, rubbing his belly.

After placing their orders, Loren asked Ruppé how long he had lived in Turkey.

“Gosh, going on twenty-five years now. I came over one summer from Arizona State to teach a marine archaeology field school and never left. We located an old Byzantine merchant trader off the shores of Kos that we excavated, and I’ve been busy here ever since.”

“Dr. Ruppé is the foremost authority on Byzantine and Ottoman marine antiquities in the eastern Mediterranean,” Pitt said. “His expertise has been invaluable on many of our projects in the region.”

“Like with your husband, shipwrecks are my true love,” he said. “Since taking the maritime studies post at the Archaeology Museum, I regrettably spend less time in the field than I’d prefer.”

“The burden of management,” Pitt concurred.

The waiter set a large plate of mussels with rice on the table as an appetizer, which they all quickly sampled.

“You certainly work out of a fascinating city,” Loren noted.

“Yes, Istanbul does live up to its nickname as the ‘Queen of Cities.’ Born to the Greeks, raised by the Romans, and matured under the Ottomans. Its legacy of ancient cathedrals, mosques, and palaces can grip even the most jaded historian. But as a home to twelve million people, it does have its challenges.”

“I’ve heard that the political climate is one of them.”

“Is changing it the purpose of your visit, Congresswoman?” Ruppé asked, with a grin.

Loren Smith smiled at the allusion. Though a long-serving House representative from the state of Colorado, she wasn’t much of a political animal.

“Actually, I only came to Istanbul to visit my wayward husband. I’ve been traveling with a congressional delegation touring the south Caucasus and just stopped off on my way back to Washington. A State Department envoy on the plane mentioned that there were U.S. security concerns about the growing fundamentalist movement in Turkey.”

“He’s right. As you know, Turkey is a secular state that is ninety-eight percent Muslim, mostly of the Sunni faith. But there has been a growing movement under Mufti Battal, who’s centered here in Istanbul, for fundamentalist reforms. I’m no expert in these matters, so I can’t tell you the actual extent of his appeal. But Turkey is suffering economic distress like other places, which breeds unhappiness and discontent with the status quo. The hard times seem to be playing right into his hands. He’s visible everywhere these days, really attacking the sitting President.”

“Aside from upsetting the Western alliances, I can’t help but think that a Turkish shift toward fundamentalism would make the entire Middle East an even more dangerous place,” Loren replied.

“With a Shia-co

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...