- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

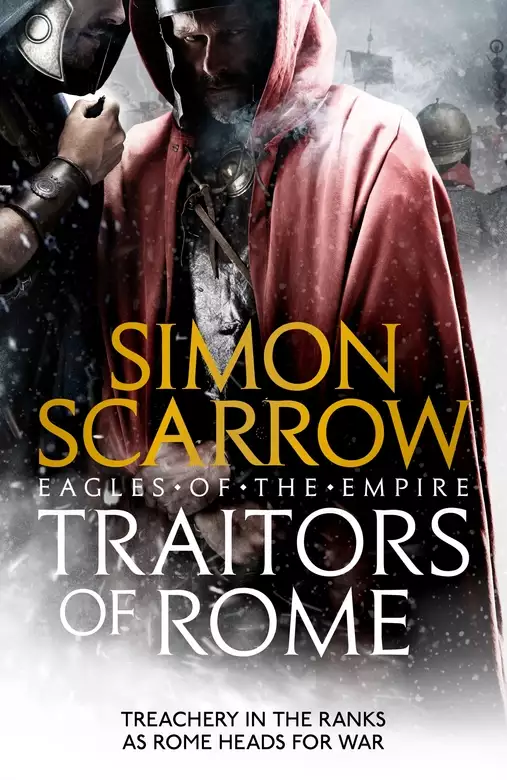

An action-packed novel of warfare, courage and camaraderie in the Roman Empire,from the Sunday Times-bestselling author

The gripping new Cato and Macro adventure in Simon Scarrow's bestselling Eagles of the Empire series. Not to be missed by readers of Conn Iggulden and Bernard Cornwell.

Tribune Cato and Centurion Macro are based on the eastern border of the Empire, facing Rome's deadly enemy Parthia. The signs are that Parthia is preparing for war. And the two battle-hardened veterans are ready for their greatest ever military challenge.

(P) 2019 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: November 14, 2019

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 359

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Traitors of Rome

Simon Scarrow

Quintus Licinius Cato: Tribune in command of the Second Cohort of the Praetorian Guard

Lucius Cornelius Macro: Senior centurion of the Second Cohort of the Praetorian Guard, a tough veteran

General Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo: Commander of the armies of the eastern Empire and tasked with the challenge of taming Parthia, while not being given the necessary resources to do so

Apollonius of Perga: an agent of General Corbulo, and aide to Cato. Transparently a shrewd and devious man, with an opaque past

Lucius: son of Cato, a delightful young boy raised amongst soldiers and picking up some of their language, alas . . .

Licinia Petronella: bride-to-be of Macro, formerly Cato’s slave. A stongly built woman with equally strong opinions

Cassius: a feral dog rescued from the wild in Armenia, now devoted to Cato and prone to terrifying those who are taken in by his fearsome appearance

Second Praetorian Cohort

Centurions: Ignatius, Nicolis, Placinus, Porcino, Metellus

Optios: Pantellus, Pelius, Marcellus

Fourth Syrian Cohort

Prefect Paccius Orfitus: recently promoted commander of the unit. A thrusting glory hunter

Centurion: Mardonius

Optios: Phochus, Laecinus

Macedonian Cavalry Cohort

Decurion: Spathos

Sixth Legion

Centurions: Pullinus, Piso

Optio/Acting Centurion: Martinus

Legionary: Pindarus

Legionary Selenus: an unfortunately hungry veteran

Others

Prefect Clodius: the edgy commander of the First Dacian Auxiliary Cohort watching over the frontier at Bactris

Graniculus: Quartermaster at Bactris. A content horticulturalist hoping for peace

King Vologases: King of Parthia, the ‘King of Kings’ and keen to impress on his subjects that the price of treachery is an agonising death.

Haghrar, of the House of Attaran: A prince of Ichnae, also known as Desert Hawk, treading delicately in the lethal world of court politics

Ramalanes: a captain of the Royal Palace Guard

Democles: a river boat captain who always has an eye open to fiscal advancement

Patrakis: river boat crewman

Pericles: an innkeeper who wishes that his customers always settled their bills in full

Ordones: spokesman for the people of Thapsis

Centurion Munius: Centurion in charge of the engineering detachment, with the thankless task of building a bridge over a raging torrent

Mendacem Pharageus: a professional rabble rouser

Legionary Borenus: another rabble rouser who may not be all that he seems

CHAPTER ONE

Autumn AD 56

‘Here they come,’ Centurion Macro muttered as he gazed towards the far side of the training ground, where a small cloud of dust indicated the approach of a column of soldiers. He finished chewing the end of an aniseed twig and tossed the frayed length aside, then spat to clear the fibrous pulp from his mouth. He turned to see his superior leaning back against the trunk of a nearby cedar tree, dozing in the shade. Tribune Cato was a slender man in his late twenties. His dark hair had been cropped short the day before and the stubble made him look like a recruit. In slumber, his face would have looked serene and youthful were it not for the white scar tissue scoring a ragged diagonal line from his forehead across his brow and down his right cheek. He was a veteran of many campaigns and he looked the part. Beside him lay his dog, Cassius, a large, wild-looking beast with wiry brown fur. One of its ears had been mauled at some point before Cato had taken the animal on a year before, when they had been campaigning in Armenia. It rested its head in Cato’s lap, and every so often its tail swished a little in contentment.

Macro regarded Cato in silence for a moment. Although he had served for twice as long as the younger man, he had come to recognise that experience was not everything. A good officer had to have brains as well. And brawn, he added to his shortlist. The latter Cato may have lacked, but he made up for it with courage and resilience. As for himself, Macro readily accepted that experience and brawn were his main qualities. He smiled as he reflected on the reasons why he and Cato had been close friends as long as they had. They each made up for the one quality the other was deficient in. It had served them well for nearly fifteen years, as they had fought through campaigns across the Roman Empire, from the freezing banks of the Rhine to the baking deserts of the eastern frontier. The two officers had an enviable record, and the scars to show that they had shed blood for Rome.

However, Macro had begun to wonder how much longer he could tempt the Fates. They had spared him thus far, but there must come a time when even their indulgence would be exhausted. Whether his death was dealt by an enemy’s sword, spear or arrow, or by something inglorious like a fall from a horse or sickness, he could sense the moment drawing closer. What he feared even more was a crippling injury that would leave him less than a man for the rest of his years.

He frowned at such morose thoughts. Five years ago he would never have entertained them. But now he was conscious that his muscles felt stiff in the morning, and there was a painful twinge in his knees at the end of a hard day’s marching. Worse still, he no longer moved as swiftly as he did in his prime. That should come as no surprise. After all, he reminded himself, he had already served with the army for over twenty-six years. He was entitled to request his discharge and take his bounty and the grant of a small plot of land, as was his due, and settle into retirement. That he had chosen not to do so was simply because he had not been able to imagine a life outside of the army. It was his home, and Cato and the others were his family.

But now he had a woman in his life.

He smiled as his mind filled with the image of Petronella; bold, brassy and beautiful in precisely the way that Macro valued beauty. She was well-built, with dark eyes set in a round face, and while her tongue could be sharp, her hearty laugh warmed his heart through and through. It was partly because of her, and partly because of the burden of his years, that Macro was now giving more and more thought to the notion of retiring from the army. And yet he felt guilty when he caught himself contemplating applying for a discharge. It was as if he was betraying the men under his command and, more importantly, letting down his friend, Tribune Cato.

He would have brooded on this more, but there was no time for that now. There was work to be done.

Macro cleared his throat as he approached the tribune. ‘Sir, the Syrian lads have arrived.’

Cato opened his eyes, then blinked at the bright sunlight just beyond the boughs of the cedar tree. The dog raised its head and looked up questioningly. Cato gave it a brief pat on its neck, then eased himself up onto his feet and stretched his shoulders as he made a quick mental calculation. ‘They’ve taken their time. They were supposed to be here at noon. That was at least an hour ago.’

The two officers squinted across the expanse of dry ground stretching out from the treeline. The auxiliaries of the Fourth Syrian Cohort were tramping along the track that led from the city of Tarsus to the training area. They were just one of the units from the army that was being assembled by General Corbulo to wage war on Rome’s long-standing eastern enemy, Parthia. Several auxiliary cohorts and two legions were in camp outside Tarsus, over twenty thousand men in all. It would have been an impressive figure, Cato reflected, were it not for the poor quality of most of the men and their equipment. Consequently there was no question of the campaign beginning until spring, at the earliest. In the meantime, Corbulo had given instructions for his men to train hard while equipment and stocks of food were gathered in to supply the army.

For its part, the Syrian cohort had been ordered to make a ten-mile route march in the country surrounding the city before heading to the training ground to carry out a mock attack on a stretch of defences that Cato’s men had erected a short distance to his right. It measured a hundred paces end to end, with a gate halfway along its length. Already the men of the Second Praetorian Cohort were emerging from the shade to take their positions along the packed earth rampart that ran behind the timber palisade. In front of them was a ditch that completed the defences.

Cato looked over his men with an experienced eye and felt a familiar surge of pride swell in his heart. These soldiers, in their off-white tunics and segmented armour, were without doubt the finest men serving in General Corbulo’s army. They had already proved their worth fighting in Spain, and in the previous year’s campaign in Armenia. The thought of the latter caused Cato’s pride to subside as he recalled the men he had lost in a bid to place a Roman sympathiser on the Armenian throne. The three hundred survivors represented just over half the number that had marched out of their barracks on the edge of Rome when the cohort had been sent east to act as Corbulo’s bodyguard. When they eventually returned to the city, there would be much grieving for their families, as well as the need to find replacements for training.

Hopefully, Cato reflected, that training would proceed more swiftly than was the case with the units of the Eastern Empire. For too long they had served as garrison troops, keeping order amongst the local people and ensuring that taxes were collected. Very few of them had ever been on campaign, and they lacked fitness and experience of battle. Corbulo had spent the last year gathering his forces for the coming invasion of Parthia, and many of the men were ill-equipped and unready for war. The Syrian auxiliaries tramping towards the Praetorians were typical of the poor calibre of men under the general’s command.

The dog nuzzled Cato’s hand and then jumped up, resting its long forelegs against his chest as it tried to lick his face.

‘Down, Cassius!’ Cato pushed it away. ‘Sit!’

At once the animal went down on its haunches, the tip of its tail still wagging.

‘At least someone can be trained,’ said Macro. ‘I’m starting to wonder if we’d be better off with a pack of dogs rather than those layabouts.’

There was a shout from the officer riding at the head of the Syrian column as he raised his arm, and the soldiers shambled to a halt. Without waiting for permission, some of the men lowered their spears and shields and bent over, gasping for breath. The commanding officer wheeled his mount and rode back down the column, berating his subordinates and gesturing furiously.

Macro shook his head and spat to one side. ‘Just as well today’s drill ain’t an ambush, eh?’

Cato nodded. It was easy enough to imagine the chaos that would have caused amongst the exhausted auxiliaries. ‘Get our men ready. I want them to go in hard when the Syrians make their attack. They need to understand that we’re not playing at war. Better a few bruises and broken bones now than have them thinking it’s going to be a gentle stroll into Parthia.’

Macro grinned and saluted before striding out in front of the length of rampart. He halted near the middle and turned to face the Praetorians. They had been issued with training weapons: wicker shields, wooden swords and javelins with blunt wooden heads. Though designed to cause less damage than the real thing, such weapons could still deliver painful blows and injuries. He raised his centurion’s vine cane and patted the head of the gnarled length of wood in the palm of his spare hand as he addressed the men in the clear, loud voice he had perfected over the years for training soldiers and commanding them in battle.

‘Time for a little exercise, lads! There’s nearly six hundred auxiliaries over there. Twice as many as us. And that’s bad odds for them.’ He paused to allow the men to smile and chuckle. ‘That said, if even one of those idle bastards gets over the rampart, I’ll have every last man of the century manning that stretch on latrine duties for a month. And since the remaining men will be fed a diet of prunes, you will be so deep in the shit that you will be dreaming of fresh air!’

There was a chorus of laughter from the Praetorians, and Macro indulged them a moment before he raised his cane to command their silence. ‘Never forget, we are the Second Praetorian Cohort, the finest body of men in the entire Imperial Guard. Now let’s show these Syrian layabouts why!’

He punched his stick into the air with a savage roar, and the Praetorians followed suit, stabbing the rounded tips of their training javelins towards the heavens as they shouted their battle cries. Macro encouraged them for a moment longer before he turned away and strode back to join Cato and his dog. Cassius’s remaining ear had pricked up at the sound of the cheering, and now he rose back onto four feet, his hindquarters swaying as his bushy tail swept from side to side. Cato took a sturdy leather leash from his belt and tied it to the dog’s iron-studded collar as he muttered, ‘Can’t be having you eat any of the Syrians . . . Bad for morale.’

Taking a firm hold on the leash, he straightened up and looked out over the open ground towards the Syrians. The centurions and optios were busy marshalling their men into a battle line opposite the rampart. Cato saw that the lines were poorly dressed even as the officers pushed and shoved the auxiliaries into position.

Macro stood with the top of his cane resting against his shoulders and let out a long sigh. ‘Sweet fucking Mars, have you ever seen such a shower of shite? I wouldn’t bet on that lot being able to fight their way out of a roll of wet papyrus. If they ever go up against the Parthians, they’d better pray that the enemy kill themselves laughing, or they haven’t got a hope.’

A glint on the track behind the Syrians drew Cato’s eye, and he saw several riders approaching. They were bareheaded, but wearing gleaming breastplates. ‘Looks like Corbulo has taken an interest in today’s drill.’

Macro sucked his teeth. ‘Then he’s in for a bit of a disappointment, sir.’

They watched the general and his staff officers ride round the far flank of the Syrian cohort before drawing up a short distance beyond to observe. Cato glanced at the prefect in command of the auxiliaries and felt a brief twinge of pity for the heavy-set and balding man. Paccius Orfitus was a decent enough officer. He had served as a legionary centurion on the Rhine frontier before being promoted to command the Syrian cohort barely a month before, and had only just begun training his men for the coming campaign. And now he had the additional burden of carrying out an attack drill under the scrutiny of his commanding general.

With the cohort formed up in two lines of three centuries, Orfitus dismounted, took his shield and helmet down from the saddle horns and armed himself to lead the formation. Like the Praetorians, the auxiliaries had been issued with training equipment that was heavier than their field kit, and no doubt added to their evident exhaustion. Orfitus waited until the colour party took their place between the two lines, then paced to the front of his cohort and gave the order to advance. The glint of the sun on their helmets shimmered as the formation rippled forward.

Macro watched for a moment before he commented grudgingly, ‘At least they can keep in step. That’s something for the prefect to be thankful for.’

Cato nodded and then jerked his thumb towards the rampart. ‘Better get yourself up there with the lads.’

‘You not joining in the fun, sir?’

‘No. Just observing.’

Macro shrugged, then saluted before jogging off behind the rampart to pick up his kit and join his men. Cato was left alone with the dog. Sometimes, he reflected, it was best to stand apart from such drills to get an overview; it was easy to miss important details from the heart of the action. He wanted to see how his own cohort performed during the exercise.

The Syrian auxiliaries steadily closed the distance, and then, just out of arrowshot, Orfitus gave the order to halt. His men drew up and there was a moment of shuffling amid the shouting of the officers to dress the line, before the formation stood still and awaited his next command.

‘Second Century! Prepare to form testudo!’

Cassius pulled on his lead and Cato tugged him back as he watched the auxiliaries in the centre of the front line form into a column. When they were ready, their commander moved into the front rank and shouted the order. ‘Form testudo!’

What followed was every bit as bad as Cato had anticipated. Those in the front rank were supposed to present their shields to the enemy before the second rank raised theirs overhead, followed by each rank in turn. Instead, many men moved to lift their shields as soon as the order was given, causing chaos as they knocked into the men around them and clashed shields with the surrounding ranks. Once again the air filled with the curses and bellowed instructions of the junior officers as they struggled to restore order. In the end, Orfitus was obliged to make his way down the column, overseeing each rank’s efforts to adopt the formation. From the rampart came a ragged chorus of jeers and laughter as the Praetorians looked on.

When at last the century was ready, Orfitus returned to his position and gave the order for the cohort to advance. The men of the two flanking centuries began to open their ranks as they prepared to hurl their training javelins. At the same time, they raised their shields until the rims covered most of their faces. Glancing back towards the rampart, Cato could make out the crest of Macro’s helmet as the centurion hefted his own javelin and waited for the Syrians to come within easy range. The mockery and taunts faded, and a relative quiet fell over the training ground as the men on both sides prepared to engage. Cato looked on with professional approval. This was as it should be. Training was a serious matter. It was the quality of their training that allowed the armies of Rome to dominate a vast empire and defeat the barbarians who regarded its riches with envious eyes.

‘Prepare javelins!’ Macro bellowed.

The men along the rampart eased back their throwing arms and widened their stance before bracing themselves. Then they stood still, like sculptures of athletes, thought Cato, as the Syrians tramped closer, sheltering warily behind their wicker training shields.

‘Loose javelins!’ Macro ordered.

The Praetorians stretched back their throwing arms and then hurled the weapons into the air with a ragged chorus of grunts. Cato watched the shafts, dark against the clear sky, as they arced towards the auxiliaries. The men of the front rank stopped in their tracks, causing disruption as those behind were forced to draw up. Even so, there was just time to duck behind their shields as the training javelins pelted down. Their light construction and blunted tips meant that there would be few injuries, but the auxiliaries’ instincts made them hesitate and take cover, just as they would in a real battle. It was up to their officers to keep driving them forward.

‘Don’t stop!’ Orfitus bellowed. ‘Keep moving! Advance!’

He called the pace as the testudo edged forward, with the flanking centuries keeping up on either side. On the rampart, fresh javelins were being passed forward to the men along the palisade, and the Praetorians were hefting them as they prepared to unleash another volley. But the attackers got in first, the centurion on the right of the line raising his sword and calling out to his men.

‘First Century! Halt! Ready javelins! Loose!’

The rushed sequence of orders led to a ragged response from the Syrians. Already tired from their forced march, many of the men were unable to throw the training javelins far enough, and the shafts plucked handfuls of soil from the foot of the rampart or fell into the ditch. Less than half, Cato judged, struck at the palisade and the men standing behind it. The Praetorians had raised their shields, and the shafts clattered aside, save for one lucky shot that caught one of the men on the shoulder. He stumbled back a pace before losing his balance and rolling down the rear of the rampart in a cloud of dust and loose soil.

As soon as the men on the other flank realised that their comrades had unleashed their volley, they followed suit, with just as little effect. By contrast, the Praetorians’ second throw was well ordered, and the javelins clattered down on the auxiliaries’ shields with a brief rattling staccato, causing some of the more nervous men to lose grip of their shields.

Orfitus continued to count the pace as he led the testudo towards the narrow causeway in front of the gate, where Macro was positioned. On either side individuals snatched up the training javelins from the exchange of volleys and hurled them back at the opposition in a steady flow of shafts to and fro. As the testudo reached the causeway, Orfitus ordered his men to halt. And Cato wondered what the prefect was planning to do next. The assault ladders were in the rear with the three centuries of the reserve line. There was a brief pause as they were brought forward and fed through the testudo, ready to be thrown up against the rampart for the assault to begin. Then it would be man on man between the auxiliaries and the Praetorians, and he had little doubt that his cohort, though outnumbered, would be able to hold the rampart.

‘Form pontus!’ Orfitus called out. At once the leading ranks of the testudo ran across the causeway and raised their shields, bracing their spare arms against the timbers of the gate. As the following ranks moved up, adding their shields and each assuming a lower posture, the bridge of overlapping shields began to form a ramp leading up to the palisade.

Cato tensed in surprise, and then smiled grudgingly. He had not expected this bold manoeuvre, particularly from a unit he had been ready to dismiss as third rate. ‘Well, well,’ he mused quietly, realising how well this must have been rehearsed.

Some of the Praetorians along the palisade were equally surprised, and leaned forward to observe Orfitus and his men, until their officers bawled at them to face the front.

‘Seems like our friend Orfitus is more than a little resourceful . . .’ Cato clicked his tongue and fondled Cassius’s ears.

The dog twitched its head to one side and gave its master’s fingers a quick lick, then gently eased forward until restrained by the taut leash.

‘Keen to get stuck in, eh? Not this time. Those men are on our side, boy.’

Cato focused his attention back towards the causeway. The new formation was almost complete, and the century that had been following the testudo was trotting forward to advance over the makeshift assault ramp. Ahead of them the Praetorians stood waiting, training swords levelled at the edge of the wicker shields, ready to strike. But there was no sign of Macro’s crested helmet amongst them. Cato frowned, wondering what had become of his friend in the moment the dog had distracted him. Had he been knocked down? Or slipped back off the rampart? That was hard to believe, as Macro had the veteran’s keen awareness of danger, as well as sure-footedness in the heat of battle. So what had happened?

He noticed a party of men gathering behind the gate, a half-century or so, in tight formation. Above them their comrades were duelling with the first of the auxiliaries to reach the palisade, wooden swords striking at wicker shields, helmets and exposed limbs with the flat of their weapons. Already, one of the Syrians was attempting to climb over the palisade to gain a foothold on the walkway above the gate.

Just then there was a roar as Macro and the Praetorians opened the gates and bellowed their war cries as they surged forward. A tremor went through the auxiliaries who formed the assault ramp. A handful of the men making their way up to the fight toppled off and rolled into the ditch on either side before the formation crumbled into a confused mass of men struggling to stay on their feet. Then Cato saw that the gate had been opened, and there was Macro’s crest bobbing above the fray as he and his men drove forward, thrusting the attackers back and causing yet more men to tumble into the ditch. Prefect Orfitus tried to rally his men at the end of the causeway, but there was no time to steady them before the Praetorians charged on into their disordered ranks. Cato caught one last glimpse of Orfitus before he was knocked down, then his men turned and fell back before Macro’s onslaught.

Cassius tugged at the leash again. He strained and looked up at Cato plaintively.

‘You want to play?’

The dog wagged its tail and Cato loosened his grip. At once Cassius bounded forward, the leash whipping from side to side behind him.

Cato shrugged. ‘Whoops . . .’

More of the Praetorians clambered down inside the defences and poured out of the gate in pursuit of the retreating Syrians, roughly knocking them down or tripping them over. Cassius raced in amongst them, jumping up at men from both sides as he weaved through the mayhem. Cato watched for a moment longer before strolling forward, cupping his hands to his mouth as he drew a deep breath.

‘Second Praetorian! Halt! That’s enough, boys!’

The nearest of his men turned and drew up obediently. Those further off had one last go at their opponents before following suit as the officers relayed the command. Macro gave the order for the centuries to form up, then watched with an amused grin as the downed auxiliaries struggled to their feet, retrieved their equipment and stumbled back across the training ground to where the rest of their comrades stood, catching their breath as they regarded the Praetorians warily. Cato caught sight of the crest of the prefect’s helmet as Orfitus sat up and shook his head. He made his way across, bending down and holding out his hand. Orfitus blinked and squinted up at the shape looming over him before he realised that it was Cato.

‘Your men don’t seem inclined to take prisoners, Tribune Cato,’ he gasped, then coughed to clear his throat.

Cato chuckled. ‘Oh, they’re happy enough to take prisoners as spoils of war. But there was no profit in sparing your lads, I’m afraid.’

They grasped forearms and Cato hauled the other officer to his feet. Orfitus briefly dusted himself down as he scanned the training ground and saw the last of his men limping over to rejoin the rest of their comrades. Then he glanced towards Corbulo and saw the general sitting stiffly in his saddle, his amused-looking officers exchanging comments to one side.

‘I don’t think the general is pleased with the way that went.’

‘Don’t take it too badly,’ Cato responded. ‘It was a neat move to use the pontus. I didn’t see that coming.’

‘Didn’t do us much good though, did it?’

‘Not this time,’ Cato admitted. ‘But you were up against my Praetorians. And men like Macro know just about every trick in the book, and how to counter them too.’

There was a chorus of angry shouting from across the training ground, and the officers looked round to see that Cassius had herded several men off to one side and was racing around them, nipping at anyone who tried to break away.

‘Would you mind calling off your cavalry, Tribune? I think he’s caused enough mayhem.’

Cato stuck two fingers in his mouth and gave a piercing whistle. Cassius stopped in his tracks and looked back. Cato whistled again, and the dog gave a last longing look at its prey before turning sharply and bounding back towards its master.

‘I owe you a drink when I next see you in the officers’ mess,’ said Orfitus. ‘You and that bloody wildman, Centurion Macro.’

They exchanged a nod before Orfitus marched stiffly to take command of his cohort, trying to preserve as much dignity as he could. Cassius ran up and skittered to a stop, flanks heaving as his long tongue lolled out of his panting jaws. Cato took up the leash and made his way over to where Macro was standing in front of the Praetorians drawn up before the rampart. The men stood at ease, wicker shields grounded as they laughed and joked.

‘Good work, Centurion. That was quick thinking.’

Macro grinned. ‘Coming from you, that’s praise indeed, sir. Of course, me and the boys had some help.’ He patted Cassius on the head and was rewarded with a lick.

‘Any injuries?’

‘A few bruises. Nothing to worry about.’

Cato nodded with satisfaction. ‘Good.’

They were interrupted by the thud of horses’ hoofs as the general and his staff rode up and turned to face the disordered ranks of the auxiliaries. Corbulo looked older than his forty-nine years; grey-haired, with a deeply lined face and a wide downturned mouth that made his expression appear sour and severe.

‘Prefect Orfitus!’ he bellowed. ‘Get your bloody men formed up! I’ll not have them milling around like a bunch of wasters on a public holiday!’

The hapless prefect saluted, then gave orders for his officers to have the men fall in. With much shouting, liberal use of vine canes and optios’ staffs, and shuffling boots, the six centuries of the Syrian cohort took their places and stood to attention under the glowering stare of their general. When at last they were formed up, Corbulo flicked his reins and walked his mount along the front of the unit. There was no mistaking the contempt in his expression as he regarded them. He returned to his former position in front of the centre of the cohort to address them.

‘That

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...