- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

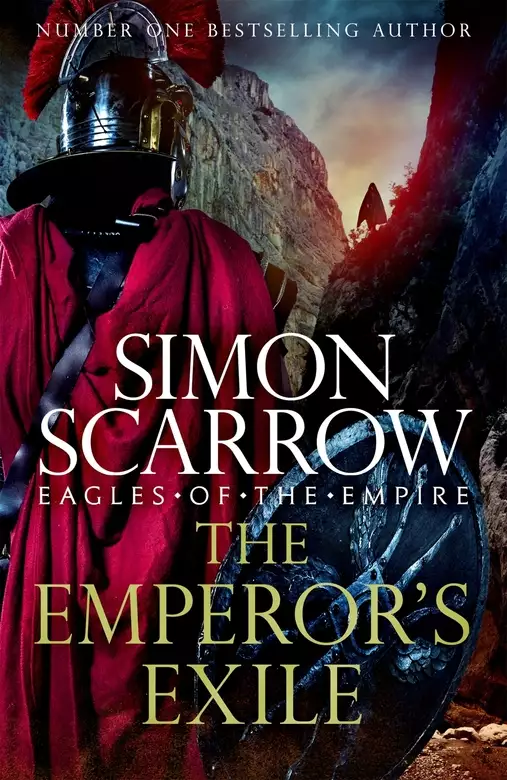

The Sunday Times bestseller - a thrilling new adventure in Simon Scarrow's acclaimed Eagles of the Empire series. Perfect for readers of Conn Iggulden and Bernard Cornwell. READERS CAN'T GET ENOUGH OF SIMON SCARROW'S BOOKS! 'I could not put it down ' ***** - AMAZON REVIEW ' Awesome read . . . ' ***** - AMAZON REVIEW 'A storytelling master. . . I loved this novel and can't wait for the next' ***** - AMAZON REVIEW 'If you have read the previous books, you already know how good they are. . . If you have not read any of these books, then get started! ' ***** - AMAZON REVIEW A.D. 57. Battle-scarred veterans of the Roman army Tribune Cato and Centurion Macro return to Rome. Thanks to the failure of their recent campaign on the eastern frontier they face a hostile reception at the imperial court. Their reputations and future are at stake. When Emperor Nero's infatuation with his mistress is exploited by political enemies, he reluctantly banishes her into exile. Cato, isolated and unwelcome in Rome, is forced to escort her to Sardinia. Arriving on the restless, simmering island with a small cadre of officers, Cato faces peril on three fronts: a fractured command, a deadly plague spreading across the province...and a violent insurgency threatening to tip the province into blood-stained chaos. IF YOU DON'T KNOW SIMON SCARROW, YOU DON'T KNOW ROME! MORE PRAISE FOR SIMON SCARROW'S NOVELS 'Scarrow's [novels] rank with the best' Independent ' Blood, gore, political intrigue' Daily Sport 'Always a joy' The Times

Release date: November 12, 2020

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Emperor''s Exile

Simon Scarrow

Rome, summer AD 57

There was a fine view of the city from the garden of the Pride of Latium. The inn was atop a small rise just off the Via Ostiensis, the road that led from the port of Ostia to Rome, some fifteen miles away. A light breeze rustled through the boughs of a tall poplar tree growing a short distance from the inn. The tables and benches in the garden were sheltered from the stifling glare of the mid-afternoon sun by an arrangement of trellises over which vines had been trained. The Pride of Latium was well positioned to take advantage of the passing trade. There were merchants and cart drivers travelling along the route that carried goods to the capital from across the breadth of the Empire, officials and tourists coming and going from the recently completed port complex at Ostia. There were travellers leaving Rome to voyage across the ocean, or, in the case of the small group seated at the table with the best view of Rome, returning to the capital after a period of service on the eastern frontier.

There were five of them: two men, a woman, a young boy and a large, wild-looking dog. They were being watched closely by the owner of the inn as he wiped ants off his counter with an old rag. He was shrewd enough to recognise soldiers when he saw them, in or out of uniform. Even though the men were dressed in light linen tunics rather than the heavy wool of the legions, they carried themselves with the assurance of veterans, and they bore the scars of men who had seen plenty of action. The oldest of the party was shorter than average but powerfully built. His cropped dark hair was streaked with grey and his heavy features were lined and scarred. But there were creases about his eyes and each side of his mouth and a ready smile that indicated good humour, as well as the marks of hard-won experience. He had fifty years under his belt, the innkeeper estimated, and must surely have reached the end of his career. The other man, sitting beside the boy, was also dark-haired but well over a decade younger, perhaps aged thirty or so. It was hard to be certain as there was a thoughtfulness to his expression and a controlled grace to his movements that revealed a maturity beyond his years. He was as tall as his comrade was short and as slender as the older man was bulky and muscular.

They were as mismatched a pair as any two men the innkeeper had seen, but they were clearly tough cases, and he was grateful they were only on their first jar of wine and sober. He hoped they would remain that way. Soldiers in their cups could be cheery and maudlin one moment, and angry and violent the next, on the merest of presumed slights. Fortunately, the woman and the boy were likely to be a moderating influence. She was sitting next to the older man and shifted closer to him as he wrapped a hairy arm around her. Her long dark hair was tied back in a simple ponytail and revealed a wide face with dark eyes and sensuous lips. She had a full figure and an easy manner and matched the men in drinking the wine cup for cup. The boy was five or so, with dark curly hair, and had the same thin features as the younger man, whom the innkeeper assumed was his father. There was a sly mischief about the child’s expression, and as the adults talked, he reached a small hand towards the woman’s cup until she swatted it gently away without even looking, as women will when they have developed the uncanny sixth sense that comes with raising children.

The innkeeper smiled as he tossed the rag into a bucket of murky water and made his way over to their table, keeping his distance from the dog.

‘Will you be having anything to eat, my friends?’

They glanced up at him and the older man replied. ‘What do you have?’

‘There’s a beef stew. Pork cuts – hot or cold. There’s roasted chicken, goat’s cheese, fresh-baked bread and seasonal fruit. Take your pick and I’ll have my girl prepare you the best roadside meal you’ll ever eat on the Ostian Way.’

‘The best food over a whole fifteen miles?’ The older man chuckled and continued in a wry tone. ‘Wouldn’t be much of a challenge to put that to the test.’

‘Leave off, Macro,’ the younger man intervened as he turned to address the innkeeper. ‘We need a quick meal. We’ll take the cold cuts of pork and chicken with a basket of bread. Do you have olive oil and garum?’

‘Yes, for a bit extra.’

‘Don’t like garum,’ the boy muttered. ‘Horrible stuff.’

The older man smiled at him. ‘You don’t have to eat it, Lucius. I’ll have your ration, lad.’

‘What’s the price?’

The innkeeper did a quick mental calculation based on the cost of the raw ingredients, but mostly based on the quality of the men’s clothing and the likelihood of them carrying their savings from their previous posting. In his experience, such men returning home tended to be willing to spend over the odds without creating a fuss. He scratched the side of his head and cleared his throat. ‘I can do you some good scoff for three sestertii a head. Garum, oil and another jar of wine included.’

‘Three sestertii!’ the woman gasped in derision. ‘Three? You are joking, mate. If we paid five for the lot we’d still be paying over the odds.’

‘Now look here . . .’ The innkeeper arranged his features into an indignant expression and took a half-step back. But she cut him off before he could go any further, thrusting a finger at him and looking down its length as if she was taking aim with an arrow.

‘No! You look here, you gouging weasel. I’ve bought food in the markets of Rome since I could walk. I’ve also been to country markets and those in the streets of Tarsus the last two years. Nowhere have I seen anyone try it on like you are doing right now.’

‘But . . . but prices have increased since you were away,’ he blustered. ‘There’s been a famine in Sardinia, and a plague, and it’s driving up costs.’

‘Pull the other one,’ she shot back.

The younger man could not help laughing. He took her hand and gave it an affectionate squeeze. ‘Easy there, Petronella. You’re scaring the man. This is my treat.’ He looked at the innkeeper. ‘Let’s split the difference, for the sake of peace and amity, eh?’

‘Ten, then,’ the innkeeper replied swiftly. ‘Can’t do it for any less.’

‘Ten?’ The man sighed. ‘Let’s call it eight, or I’ll set Petronella loose on you again.’

The innkeeper glanced at her warily and sucked in a breath between his stained teeth before he nodded. ‘Eight, then. But no wine.’

‘With wine,’ the other man insisted firmly, all trace of humour gone from his voice as he stared hard with dark eyes.

The innkeeper puffed out his cheeks, then turned and scurried back to the door behind the counter that led to the kitchen, shouting instructions at his serving girl.

‘That’s my lass,’ said Macro. ‘Fierce as a lioness. I have the scratches to prove it.’

‘You shouldn’t have paid eight, Master Cato.’ Petronella frowned. ‘It’s too much.’

Cato shook his head, mildly amused that she still deferred to him as her master on occasion. He had freed her over a year ago, after Macro’s affection for her had been made clear. And now they were married and the veteran centurion was determined to apply for his discharge so that the two of them could settle into peaceful retirement. In truth, peace might be a little bit more difficult to achieve than Macro assumed, since they were shortly bound for Britannia, where he was to take up his half of the business owned by himself and his mother. Cato knew her well enough to be sure she would match Petronella’s fierce personality claw for claw. If he was any judge of either woman’s character, then Macro was going to have his hands full. The centurion would soon be wishing he was back serving with the legions facing somewhat less fearsome conflict. Still, that was his choice and there was nothing Cato could, or would, do about it now that his friend had made his decision. He would miss having Macro around – would miss him greatly – but he must find his own way ahead. Perhaps their paths would cross again in the future if Cato was assigned to the army in Britannia.

He put thoughts of the distant future out of his mind and clicked his tongue at Petronella. ‘Let’s have no more of you calling me master. I am no more your master than your husband will ever be.’

Macro grinned and slid his hand down to slap her rump gently. ‘I’ve broken in far more challenging recruits than her in my day. By the gods, Cato, you were one of the biggest drips I’d ever clapped eyes on that night you pitched up at the Second Legion’s fortress.’

‘And look at him now,’ Petronella cut in. ‘A tribune of the Praetorian Guard. While you’ve never got beyond centurion.’

‘Each to his own, my love. I like being a centurion. It’s what I am best at.’

‘What you were best at,’ she said deliberately. ‘Those days are over. And you’d better not have any notions of treating me like some bloody recruit or I’ll give you what for.’ She bunched her fist and held her knuckles under Macro’s nose for a moment before relaxing.

Lucius nudged Cato. ‘I like it when Petronella gets angry, Father,’ he whispered. ‘She’s scary.’

Macro roared with laughter. ‘Aye, lad! You don’t know the half of it. The love of my life is as tough as old boots.’ He shot her an anxious look. ‘But far lovelier.’

Petronella rolled her eyes and gave him a shove. ‘Oh, give over.’

Macro’s expression became earnest. He raised a hand to turn her face towards him and kissed her gently on the lips. She pressed back and reached round his broad back to draw him into her. Their lips remained locked together for a moment longer before they parted, and Macro shook his head in wonder. ‘By all that’s sacred, you are the woman for me. My girl. My Petronella.’

‘My love . . .’ she replied as they stared fondly at each other.

Cato coughed. ‘Want me to see if I can get a decent rate for a room for the pair of you?’

The food arrived shortly afterwards, carried on a large tray by a thickset serving girl dripping with perspiration from working over the fire in the kitchen. She set the tray down and unloaded cuts of pork and two roast chickens heaped on a wooden platter, a wicker basket containing several small round loaves, two stoppered samianware jugs of oil and garum and another of wine. The portion sizes were more generous than Cato was expecting, and in his present good mood he felt generous enough to tip her a sestertius. She glanced at the coin in her palm wide-eyed, then looked nervously over her shoulder, but the innkeeper was at another table where two more customers had sat down. She tucked the coin into the pocket in the front of her stained stola and hurried back to the kitchen.

‘Ah, this is the life!’ said Macro as he tore off a chicken leg, closed his teeth over the seared skin and began to chew. ‘A fine sunny day. The best of company. Good food, passable wine and the prospect of a comfortable bed at the end of it. Be good to get a hot bath and a change of clothing.’

‘I’m sure there’ll be something at the house,’ Cato responded as he tossed a scrap of meat to the dog, who snapped it up and then nudged his hand for more. He smiled. ‘Sorry, Cassius, that’s the lot.’

They had left their baggage in Ostia, where one of Cato’s men had been charged with bringing it to Rome. They were bound for the large property Cato owned on the Viminal Hill, one of the city’s wealthier neighbourhoods. His promotion to commander of an auxiliary cohort some years earlier had brought with it elevation to the ranks of the equites, the social class one step beneath that of senator. He was also a man of some substance, largely thanks to being granted the property and fortune of his former father-in-law, who had plotted against the emperor. The traitors would have succeeded in assassinating Nero had it not been for Cato’s intervention. All of Senator Sempronius’s estate had been handed to him as a reward.

Such were the changing fortunes of Rome’s nobility under the Caesars, Cato reflected. He was conscious that what the emperor could give, he could just as easily take away. Now that he had a son to raise, he was determined to keep his nose clean and his good fortune intact. Not that it was going to be easy, given the poor start to the conflict with Parthia over the previous two years. An attempt to replace the ruler of Armenia with a Roman sympathiser had led to disaster, and the revolt of a minor frontier kingdom had threatened to spread before it had been crushed. Cato had played a part in both campaigns and now feared he would pay the price once he had submitted his report to the imperial palace.

A chorus of laughter drew his attention to the innkeeper and his other customers just as the former turned to shout an order to the serving girl. Then he crossed over to Cato and his companions and affected a cheery smile.

‘Tell me the food’s as good as I told you it was, eh?’

‘It is satisfactory,’ Petronella responded, and made a show of inspecting one of the loaves. ‘The bread could have been fresher.’

‘It was baked first thing today.’

‘It may have been baked first thing. But not today.’

The innkeeper gritted his teeth before he continued. ‘But the rest is good? More than satisfactory, I take it? What do you say, sonny?’ He ruffled Lucius’s curls. The youngster, jaws working hard on a bit of gristle, shook off his hand and raised his eyes.

Cato swallowed and intervened. ‘It’ll do nicely.’

Despite Petronella’s justifiable protestations, he was keen not to annoy the innkeeper unduly. Such men were useful purveyors of gossip and information that they garnered from passing trade, and there was much he was keen to know about the situation in Rome before they entered the city. He hurriedly swallowed the chunk of oil-soaked bread in his mouth and cleared his throat.

‘We’ve been on the eastern frontier for a few years.’

‘Ah!’ The innkeeper nodded. ‘Fighting those Parthian bastards, eh? How’s the war going?’

‘War?’ Cato exchanged a look with Macro. ‘It hasn’t really begun.’

‘No? Last time I was in Rome, the bulletins posted in the forum spoke of a series of frontier clashes. Said we’d given them a good kicking.’

‘Well, you can’t believe everything you read in the bulletins,’ said Macro. ‘The date given is true enough. As for the rest . . .’ He shrugged.

The innkeeper frowned. ‘Are you saying the bulletins are false?’

‘Fake bulletins? Not necessarily. But I wouldn’t bet my life savings on it.’

‘Be that as it may,’ Cato resumed, ‘we’ve been out of touch with life in the capital. Anything new we should be aware of?’

‘Over the last few years? How much time have you got?’

‘Enough to eat this meal and then we’re back on the road. So keep it short.’

The innkeeper scratched his cheek as he collected his thoughts. ‘The big news is that Pallas looks like he’s on his way out.’

‘Pallas?’ Macro raised an eyebrow. Pallas was one of the imperial freedman Nero had inherited from Claudius and was the emperor’s chief adviser. It was a post for which the requisite skills included spying, back-stabbing, greed and ambition, all of which he had honed to the sharpest degree. Only it seemed that he had been caught out, or had met his match in one of his rivals. ‘What’s happened?’

‘He’s been charged with conspiracy to overthrow the emperor. The trial’s due to start in a month or so. Should be a good show; he’s being defended by Senator Seneca. I’d be sure to go and watch the sport if I wasn’t so busy here.’

Macro shifted his gaze to his friend. ‘Bloody hell, that’s a turn-up for the scrolls. I thought Pallas had his snout squarely in the trough. What with how tightly he’d stitched things up with Agrippina,’ he concluded in a cautious tone.

Cato nodded as he reflected on the power shift in the capital. Pallas had allied himself with Agrippina and her son Nero in the last years of the previous emperor. His relationship with the new emperor’s mother was not merely political. Cato and Macro had uncovered the secret some years earlier and wisely kept their mouths shut. Not that tongues weren’t wagging around the dinner tables of the aristocrats, nor amongst the gossips who gathered round the public fountains in the slums. But rumours were one thing; knowing the truth was a far more dangerous situation. Now it seemed that Pallas’s prospects were on the wane. Possibly fatally. And not just him, perhaps.

‘Is anyone else on trial with him?’

‘Not that I know of. He might have been acting alone. More likely the emperor has got his eyes on his fortune. You don’t get to be that rich without making enemies. People you’ve done down on the way up. Or people who simply resent your success and wealth. You know how it goes amongst the quality in Rome. Always ready to stick the knife in . . . so they say.’ He glanced at Cato with a flicker of anxiety. ‘What did you say your business was in Rome again?’

‘We’ve been recalled. That is to say, my cohort of the Praetorian Guard.’

‘Your cohort?’ The innkeeper smiled weakly as he realised he had been treading on dangerous ground in offering his opinion of the emperor’s motives.

‘I’m the tribune in command. Macro here is my senior centurion. We took the first ship bound for Ostia. The rest of the men are on transports a few days behind us, so you may be in luck when they pass this way.’

‘I didn’t mean any criticism of my betters, sir. It’s just the talk on the street. I meant no offence.’

‘Easy there. Your views on Nero are safe enough with us. But what of Agrippina? Do you know if she had anything to do with charging Pallas with conspiracy? When we left for the eastern frontier, the two of them were the emperor’s closest advisers.’

‘Not any more, sir. Like I said, Pallas is on trial, and she’s fallen from favour. The emperor has kicked her out of the imperial palace and stripped her of her official bodyguards.’

‘That was Nero’s doing?’ Macro queried. ‘Last time I saw the two of them together, she had him wrapped round her little finger. Looks like the boy has grown some balls finally and is running the show. Good for him.’

‘Maybe,’ Cato mused. From his experience of the new emperor, he doubted Nero had taken such an initiative by himself. More likely his hand was being guided by another faction within the palace. ‘So who’s advising the emperor these days?’

Even though he was somewhat reassured that his words would not be used against him, the innkeeper lowered his voice. ‘Some say the real power is now in the hands of Burrus, the commander of the Praetorian Guard. Him and Seneca.’

Cato digested this bit of gossip and then arched an eyebrow. ‘And what do others say?’

‘They say Nero is a slave to his mistress, Claudia Acte.’

‘Claudia Acte? Never heard of her.’

‘I’m not surprised, sir. Not if you’ve been away for a few years. She’s only been seen in his company over the last few months. At the theatre, the races and so on. I saw her myself last time I was in Rome. Nice-looking, but the word is she’s a freedwoman, and the well-to-do don’t like that.’

‘I can imagine.’ Cato knew how touchy the more traditionally inclined senators were about social distinctions. They regarded the accident of birth that granted them huge privileges as some kind of gods-given right to treat all other people as innately inferior. The affected air of superiority of the worst of them grated on his nerves. Even if they thought their shit smelled better than that of the great unwashed, it didn’t. Moreover, the same shit tended to occupy a greater proportion of their heads than whatever residual matter passed for brains. The idea of an emperor showing off his low-born woman to the world and rubbing their noses in it would send the more sensitive of the senators into a conspiratorial frenzy. Nero was playing for high stakes, even if he was unaware of it.

‘I’ll leave you to finish your meal then, sir.’ The innkeeper nodded to Cato and his companions and made his way to his stool at the end of the counter.

Macro took a quick swig of wine from his cup, then burped and smiled. ‘Sounds like things have finally changed for the better in Rome. With luck, that snake Pallas is heading for the Underworld and won’t be causing us any more trouble. That’s worth drinking to.’ He refilled his cup and topped up Cato’s. But his friend left it on the table as he stared down thoughtfully.

‘What is it, Cato? Found some way to see a downside to the situation? Just for once, why not celebrate some good news?’

Cato sighed and picked up his cup. ‘Fair enough. But tell me, brother, from our previous experience, how often does bad news follow on from good?’

‘Ah, piss off with the pessimism and enjoy the wine, why don’t you?’

Petronella nudged him with her elbow. ‘Language! You want young Lucius speaking like that?’

Macro glanced at the boy and winked. Lucius grinned.

‘Let’s hope I’m wrong, then,’ said Cato. He raised his cup. ‘To Rome, to home, and to a peaceful life. We’ve earned it.’

Chapter Two

There was always an uncomfortable aspect to returning home after the passage of some years, Cato mused as they entered the capital and made their way through its crowded streets. Even though his senses were overwhelmed by the familiar sights, sounds and scents of the city, there was something about it that seemed strange and unsettling. That feeling that things had moved on and he was a stranger to the place where he had been born and raised. It felt vaguely diminished, too. Rome had once been the entire world to him, vast and all-encompassing. It had seemed impossible to believe that its avenues, temples, theatres and palaces could be surpassed in their magnificence, or the range of entertainments on offer bettered, or the sophistication of its libraries and scholars matched by any others in the Empire or beyond. Yet since Cato had left the city, he had seen for himself the wealth of Parthia, and the Great Library in Alexandria, whose galleries sprawled in the shadow of the towering Pharos lighthouse, far taller and more impressive than any building in Rome. But then, he reasoned, all places, as with all experiences, seemed less impressive when you revisited them. Experience constantly recalibrated the perception of memory so that the recollection of his initial wonder now felt like a slightly shameful naivety.

Even so, there was a comfort in being immersed in the familiar. A jaded sense of belonging, he decided, was better than being rootless. Despite the stench of the drains and the refuse in the street, there was the warm aroma of baking bread, woodsmoke and the heady scent of spices from the markets. Remembered streets and thoroughfares fell into place as they traced their route beside the imperial palace, across the Forum and up the slope of the Viminal Hill, passing through the crowded and crumbling apartment blocks in the slum at the foot of the hill. Taking Lucius’s hand to make sure they were not separated in the narrow, busy street, Cato looked down and saw the excited gleam in his son’s eyes as he cast his gaze at the people bustling around him.

‘Of course. When we left Rome, you were probably too young to remember much about it.’

‘I remember, Father,’ Lucius replied defiantly. ‘I’m six years old. I’m not a baby.’

Cato laughed. ‘I never said you were. You’re growing up fast, my boy. Too fast,’ he added ruefully.

‘Too fast?’

‘You’ll know what I mean when you become a father.’

‘I don’t want to be a father. I want to be a soldier.’

Cato’s expression hardened as memories, gut-wrenching as well as glorious, flitted through his thoughts. ‘There’ll be time for that another day, if it’s really what you wish for.’

‘I do. Uncle Macro says I’ll be a fine soldier. Just like you. I’ll even command my own cohort, too.’ He reached out his spare hand and tugged Macro’s tunic. ‘That’s what you said, isn’t it, Uncle Macro?’

‘Right you are, my lad.’ Macro nodded as he held Cassius’s leash firmly. Excited by the rich array of scents and noises all around him, the dog was straining to explore in every direction. ‘Soldiering’s in your blood. It’ll make a man out of you.’

Cato felt his heart sink at the prospect. Unlike his friend, he did not see warfare as an opportunity to seek glory. It was a necessary evil at best. The last recourse when every attempt at finding peaceful resolutions of disputes between Rome and other empires and kingdoms had failed. And to restore order in the event of rebellion or other civil conflict. He knew that Macro had little sympathy for his views on the matter and so the two of them rarely addressed the question head on. Which was why Cato felt irritated by Macro’s encouragement of his son. He knew his friend well enough to understand that this was not an attempt to use Lucius as a proxy in their differing views; just innocent encouragement. That made it all the more difficult to counter without making it look as if he was overreacting. Distraction would be a better strategy.

‘We must find you a tutor once we get settled, Lucius.’

The boy scowled. ‘Don’t want one. I want to play with Uncle Macro and Petronella instead.’

Cato sighed. ‘You know perfectly well that they will be leaving Rome soon. You’ll need someone to look after you and start your education once Petronella is no longer around.’

She shot him a dark look. ‘I’ve taught him his letters and numbers, master. And some reading.’

‘Of course. I apologise . . . Thank you. It’s not going to be easy to replace you.’

Mollified, she nodded. ‘I’ll see if I can find someone you can trust. I’ll ask round the other households on the Viminal. There’s bound to be someone who can take my place.’

‘My love,’ Macro smiled, ‘no one can take your place. Why, you’re practically a second mother to the lad.’

‘I don’t want her to go,’ Lucius muttered, lowering his gaze. ‘Can’t they stay?’

‘We’ve talked about this, son,’ Cato replied. ‘They have their own life to lead.’

‘Can’t you order them to stay, Father?’

‘Order them?’ Macro roared with laughter. ‘I’d like to see anyone order Petronella to do something. I’d pay good money to watch them being pulverised.’

They turned into the street where Cato’s house sat. There were small shops on either side, leased from the owners of the large properties that lay behind them. At the near end of the street were a few apartment blocks, which gave way to the houses of their wealthier neighbours. The entrances to the larger properties lay between the shops and presented large studded doors to the street. As they reached Cato’s home, halfway along, he saw that the ironmonger and the baker who rented their premises from him were still in business on either side of the modest run of steps that rose from the street to the front door. He paused briefly to admire the neatly maintained timbers and bronze studs and then climbed the steps and rapped the knocker sharply.

An instant later, the narrow shutter snapped back and a pair of eyes inspected him briefly through the grille before a muffled voice demanded, ‘What is your business?’

‘Open the door,’ Cato ordered impatiently.

‘Who are you?’

‘Tribune Quintus Licinius Cato; now open up.’

The eyes narrowed before the doorman responded, ‘A moment.’

The shutter rattled back into place and Cato turned to the others. ‘Must be a new doorman. Else I have changed more than I thought since we were last in Rome.’

The shutter slid open again and an older man appeared at the grille. One glance was enough; the bolts on the far side were drawn back and the door swung open to reveal Croton, the steward of the household. He bowed quickly and smiled readily as he stepped to the side to allow Cato and the others to enter. ‘Master, it does my heart good to see you all return. We had no idea you were coming home.’

‘We only landed at Ostia yesterday. We’ve been on the road since first light.’

Croton swiftly got over his surprise as he closed the door and shut out the noises from the street. In the quiet entrance hall the only sound was the light tinkle from the fountain in the atrium beyond.

‘I’ll have the sleeping chambers and living spaces prepared at once, master. And you’ll be needing food after your journey.’

‘Food can wait,’ Cato interrupted. ‘What we want is a bath and fresh clothes. Have the bathhouse fire lit and then see to the other matters.’

Croton looked them over and cocked an eyebrow. ‘And your baggage, sir?’

‘Coming upriver from Ostia. Should reach the house tomorrow. It’ll be in the charge of a man called Apollonius. He’ll be staying in the house with us, so have a room ready for him too.’

‘More’s the pity,’ Macro muttered. He had little affection for the spy who had acted as Cato’s guide during his recent mission to Parthia and had agreed to serve with the tribune when the Praetorian cohort returned to Rome. Not that there were many men left on the unit’s strength, he mused. No more than a hundred and fifty out of the original six hundred or so had survived the battles of the last two years. Even though

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...