- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

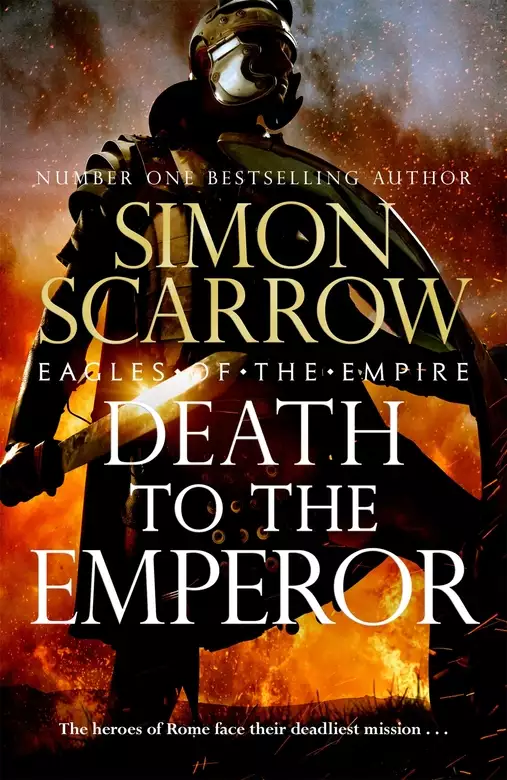

1st-century Britannia is the setting for an epic and action-packed novel of tribal uprisings, battles to the death and unmatched courage in the Roman army ranks. From Simon Scarrow, author of the bestsellers The Emperor's Exile, Centurion and The Gladiator.

The 21st Eagle of the Empire novel. If you don't know Simon Scarrow, you don't know Rome!

It is AD 60. The hard-won province of Britannia is a thorn in the side of the Roman Empire, its tribes swift to anger, and relentless in their bloody harassment of the Roman military. Far from being a peaceful northern enclave, Britannia is a seething mass of bitter rebels and unlikely alliances against the common enemy. Corruption amongst greedy officials diverts resources from the locals who need them. For the military, it's a never-ending fight to maintain a fragile peace.

Now it's time to quell the most dangerous enemy tribes. Two of Rome's finest commanders - Prefect Cato and Centurion Macro - are charged with a mission as deadly as any they have faced in their long careers. Can they win the day, or could this be the last battle?

A stunning and unforgettable story of warfare, courage and sacrifice as brave men face an enemy with nothing to lose . . .

(P) 2022 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: November 10, 2022

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death to the Emperor

Simon Scarrow

He took a pace back and lowered himself into a crouch, weight instinctively balanced so that he was poised to spring forward or aside instantly, the result of over thirty years of soldiering. Raising his wooden training sword, he inscribed small circles with the blunted tip.

‘Now, Lucius,’ he instructed. ‘Get it right this time.’

Opposite him a thin boy, some eight years of age, with a mop of unruly dark curls, gritted his teeth and adopted a similar stance as he readied himself to attack. His dark eyes narrowed and he glared back at Macro. They stood on the gravel to one side of the small tiled pond in the courtyard of Macro’s house. Two women and another man were watching from the chairs arranged around a wooden table at the end of the garden. At the man’s feet curled a huge dog with wiry hair, its long head stretched out between its front paws. They were warmed by the logs burning in an iron-framed basket set before them, and yet they still needed cloaks. Like most of the Romans who had come to settle in the new province of Britannia, they were not used to the clammy cold of the island’s winters. Macro and Lucius, by contrast, wore only simple tunics, and had worked up a sweat as they exercised in the courtyard.

‘Give it to him, Lucius!’ one of the women called out cheerfully. She was a firmly built woman with a kindly round face, brown eyes and dark hair.

Macro frowned at her. ‘Thanks for the loyal support, wife.’

Petronella laughed and flapped a hand dismissively.

He was about to respond when the boy let out a shrill cry and charged at him, thrusting at his midriff. The centurion parried the blow easily and made a riposte, aiming at the centre of the lad’s chest. Back swept the smaller training sword and rapped against Macro’s weapon as Lucius rushed in to strike at his opponent’s stomach. Despite his heavier frame, Macro moved fluidly out of the way and the point of the boy’s sword cut through the air at his side. He was about to slap the boy on the shoulder again when Lucius brought his heel down on the exposed toes of Macro’s leading foot.

‘Ah!’ the centurion cried out in surprise as much as pain, and hobbled back a step. ‘Why, you cunning little bastard—’

‘Mind your language!’ his wife shouted.

Before Macro could respond, Lucius had darted back a pace and lunged at the centurion’s chest. The point landed squarely just beneath his ribcage, a sharp prod that merely injured his pride for a heartbeat before he grinned and lowered his sword. ‘That’s it! Well done, Lucius!’

The youngster’s ferocious expression relaxed into a look of proud delight, and he turned to the bearded man seated at the table. In his mid thirties, the latter was slender and had the same dark curls as his son. His face bore a vivid diagonal scar from brow to cheek, but it did not mar his sensitive good looks. He returned the smile, and then his mouth opened to give a warning, but he was too late. Macro slapped Lucius on the wrist with the flat of his training sword, just hard enough to cause the boy to drop his own weapon.

He yelped and scowled at the centurion.

‘Never turn your back on your opponent while he’s still on his feet,’ Macro admonished him. ‘How many times have I told you that, eh?’

There was a serious tone to his voice, and Lucius lowered his head as he rubbed his wrist and muttered, ‘That hurt.’

‘That’s as nothing compared to the hurt you’ll feel from the sword that’ll be stuck through your spine if you ever do that in a real battle.’

Lucius pressed his lips together and his chin trembled in wounded pride. Macro saw that he was on the verge of tears and did not want to let the boy embarrass himself. He ruffled his hair affectionately and spoke softly. ‘No harm done, lad. No shame in making mistakes when you’re only just learning how to use a sword. I was the same when I started out.’ He glanced towards the table and grinned. ‘Your father was one of the most hopeless recruits ever to join the Second Legion. More of a danger to himself and his comrades than the fiercest German warrior that ever breathed. Ain’t that the truth, Cato?’

Cato grimaced. ‘If you say so, my friend.’

‘And look how he turned out,’ Macro continued as he placed a hand on Lucius’s shoulder. ‘Risen through the ranks from optio to prefect, and on the way he’s served as a tribune of the Praetorian Guard and picked up more awards for bravery than most soldiers do in a lifetime. One of the finest officers in the army, without a doubt. So you keep practising, young Lucius, and one day you may achieve as much as your father has, eh?’

The fair-haired woman beside Cato looked at him warmly, then reached over and planted a soft kiss on his scarred cheek. ‘My hero.’

‘Enough of that, Claudia.’ Cato recoiled with a frown. It was not in his nature to take praise easily. ‘Just do your best, son. No one can ask more of you than that.’

The boy came to the table and squatted beside the dog to stroke it. The animal wagged its tail happily, then suddenly lifted its head and licked his face.

‘Oh Cassius! Stop.’ The boy laughed as he rose and sat on one of the spare stools, his feet not quite reaching the ground. He looked up at Cato. ‘If you are a good soldier, Father, then what are we doing here in Camulodunum? Surely you should be on the frontier, fighting the barbarians and the Druids for the emperor.’

There was an exchange of glances amongst the adults. The truth was that Claudia had been Nero’s mistress before being sent into exile on Sardinia. She had since left the island to be with Cato and they had been forced to come to the furthest corner of the Empire to keep her safe. The veterans’ colony of Camulodunum was a quiet backwater where the chances of her being recognised and reported were small. But not small enough that they could risk letting Lucius inadvertently reveal the true reason behind their presence there.

‘Your father is resting between campaigns,’ said Petronella. ‘He needs to be ready for when the emperor next needs him. Besides, he wants to spend more time with you. You like it here, don’t you, Lucius?’

The boy thought a moment. There were other children at the colony his own age to play with, and in the summer there was fishing on the river and hunting in the woods that surrounded Macro’s farm, half a day’s journey away. He nodded. ‘I suppose so. But it’s getting cold again.’

Macro sighed. ‘Aye, too true. The bloody winter in this province was made by the gods to test us. Cold, damp and clammy. The roads turn to thick mud that’ll suck your boots off, and we’re stuck with eating salted meat and whatever fresh vegetables we can store.’

‘Keep going,’ Petronella said archly. ‘You’re doing a fine job of cheering the lad up.’

Cato reached for his cup of warmed wine and took a sip. ‘Ah, come on, Macro. It’s not so bad. You’ve done well enough out of it.’ He gestured to the house around the courtyard. It had once been the legate’s quarters when a legionary fortress had been under construction. The work had been abandoned when the decision had been taken to establish the colony on the site instead. There were still many former military buildings in the settlement, although much of the rampart had been demolished and the defensive ditch filled in. Amid the existing buildings there was much new construction, including a forum, a theatre, an arena, and an imposing temple complex dedicated to the imperial cult.

‘You have the finest place in the colony, Macro. You’ve also a profitable farm in the country and you are the senior magistrate of the colony’s senate. To cap it all, you enjoy the greatest of fortune in having Petronella for a wife.’ Cato raised his cup to her and bowed his head gently. ‘I’d say you were sitting pretty. A fine end to your military career, my friend. You’ve earned it. You can live out your retirement in peace and in comfort.’

Petronella smiled, then took her husband’s brawny arm and hugged it.

‘I suppose so,’ Macro said. ‘Though I can’t help missing the old life some days.’

‘You’re bound to. But you couldn’t serve in the army forever.’

‘I know,’ Macro said sadly.

There was a pause before Claudia cleared her throat. ‘It is peaceful here, but it might be wise not to take it all for granted.’

Cato turned to his son. ‘Why don’t you go and see if your friends want to play?’

The boy’s gaze shifted to the wooden training swords lying on the table. ‘Can I take those with me?’

‘As long as you’re careful,’ said Cato. ‘I don’t want to hear about any broken bones or bloodied noses. Understand? And take Parvus with you.’

Before Cato could change his mind, Lucius snatched the swords and trotted off towards the kitchen block at the rear of the house. He emerged a moment later with a lanky boy a few years older than himself. Parvus was a mute whom Macro and Petronella had rescued from the wharves of Londinium the previous year and adopted into their household. The four adults stared after the boys as they ran back through the courtyard and disappeared into the corridor that led to the front of the house. Macro chuckled. ‘I dare say there’ll be a few kids going home with bruises and grazes before the day is out.’

Cato nodded and smiled faintly before turning to Claudia. ‘I don’t think it’s wise to discuss certain things in front of Lucius. He’s a good boy, but children have a way of repeating things they overhear.’

‘I know. I’m sorry.’ She folded her hands. ‘But you know as well as I do that the future of the province hangs in the balance. I heard Nero say it many times when I lived at the palace. He hates this island. It’s a constant drain on the treasury and he’d rather spend the silver on entertainments in Rome, keeping the mob happy. It’s taking far longer than expected to subdue the tribes that haven’t accepted Roman rule. Every year the legions and auxiliary cohorts need fresh recruits to replace the losses they’ve sustained.’ She shrugged and shook her head. ‘Truly, I don’t know how much longer he’ll put up with it.’

‘He’d be a fool to abandon Britannia,’ Macro growled. ‘We’ve paid for this province with our blood. At least us soldiers have. If Nero throws all that aside, there’ll be many here, in the ranks as well as the colony, who’ll be thinking it’s time we had a new emperor. Besides, most of the work has been done. The lowland tribes present no threat. They’ve been conquered or disarmed and have signed treaties with Rome. The Brigantes in the north are under our thumb and the only remaining hostiles are in the mountains to the west. The new governor’s made it clear that he’s going to see to them. Ain’t that right, Cato?’

The younger man nodded. ‘That’s the news from our friend Apollonius in Londinium. Suetonius is concentrating men at Deva to strike into the mountains. It’ll be tough going. Macro and I were part of the previous attempt. It didn’t end well.’

‘That’s because the campaign started too late in the year,’ Macro interrupted. ‘If it wasn’t for the weather, we’d have done for those bastards in the hill tribes. We’d have taken Mona and put an end to the Druids too.’

‘But we didn’t,’ said Cato. ‘And now that they have a victory over Rome under their belts, they are going to be even more difficult to subdue. If anyone can do it, Suetonius is the man. He has experience in mountain warfare. Did fine work in Mauretania a few years back. I imagine he was hand-picked for this job.’

‘Or he pushed himself to the front of the queue.’ Macro grinned. ‘One last chance to put the seal on his reputation. You know what these aristocrats are like. Anything to add lustre to the family name and outdo the deeds of their ancestors and their political rivals.’

‘Will this Suetonius need to call up the reserves?’ Petronella asked.

Macro took her hand and squeezed it affectionately. ‘Not likely. There’s too few of us here to make much of a difference if we were recalled to the ranks. In any case, we’re needed here. The governor knows the value of having a small force of veterans around to ensure that none of the local tribes are tempted to play while the cat’s away.’

Claudia gave a wry smile. ‘I thought you said the lowland tribes posed no threat.’

‘So they don’t,’ Macro replied firmly. ‘The Trinovantes around Camulodunum are as meek as lambs.’

‘I’m not surprised,’ she said. ‘They’ve been harshly treated by the veterans at the colony, so I’m told. Their lands have been seized, and some of their men taken away and forced to serve in the auxiliary cohorts, while I’ve heard that many of the women have been violated.’

‘There’s always a little trouble early on,’ Macro countered. ‘The lads of the colony are used to soldiering. It takes a few years before they get the hang of being civilians.’

‘And in the meantime, the tribespeople just have to put up with it?’

‘That’s how it is,’ said Macro. ‘We’ve conquered this place, just like we’ve conquered lands from here to the deserts of the east. Once they accept their lot, the tribes will be content with being part of the Empire.’

‘I wonder.’ Claudia turned to Cato. ‘What do you think?’

Cato paused to collect his thoughts. He wasn’t as convinced as Macro about the security of this part of the new province. The year’s harvest had been poor, and that wouldn’t be taken into consideration when the tax collectors made their demands on the local people. Hunger and poverty caused discontent, and while the Trinovantes seemed docile enough, it was hard to imagine that the indignities and suffering they had endured at the hands of their newly imposed Roman masters would not cause bitter resentment, even if they were careful not to show it. If Governor Suetonius and his legions were campaigning across the far side of the province, it might tempt the hotheads amongst the local tribespeople to take advantage of the situation. Macro and the veterans at the colony were tough enough and able to put down any small-scale flare-ups, but a concerted uprising would present a real danger to the Roman inhabitants of Camulodunum.

He considered a moment longer before he responded to Claudia’s question. ‘As long as there are legions in Britain, I doubt there will be any serious trouble in this area. The Iceni have had a taste of what defying Rome means. They’ll not be anxious to repeat the experience. As for the Trinovantes, who knows? The bigger worry is what happens if Nero does decide to withdraw the legions. There are tens of thousands of Romans and other people from the Empire who have settled here. They’ll be easy meat for any tribes that decide to attack them. The choice will be between staying and trying to defend what they hold, and abandoning their homes, their property and their future here and fleeing back across the sea to Gaul.’

Claudia turned to Macro and Petronella. ‘If Nero pulls the legions out, what will you two do?’

Macro glanced at his wife, but she did not meet his eyes. ‘I’d not want to give it all up. Everything we own here, and the half-share in my mother’s business in Londinium . . . I just don’t know. I hope it never comes to that.’

‘I’ll drink to that,’ said Cato, keen to put his best friend at ease. ‘It’s hard to believe Nero will abandon Britannia. To give it up now would be a dangerous blow to Roman prestige. You can imagine how the mob would react to that, not to mention those senators who keep telling them how invincible Rome is.’

‘See?’ Macro nudged Petronella. ‘The lad’s got a handle on how it is.’

‘There’s another reason why Nero will be reluctant to pull the legions out,’ Cato continued. ‘If he withdraws them to Gaul, that will give the governor there a significant number of extra soldiers. Those who command powerful armies might be tempted to use them for political ends. So it’s safer to keep those legions tied down here in Britannia.’

Macro tutted. ‘You have a devious mind, lad. A cynical mind.’

‘I’m a realist.’ Cato shrugged. ‘We’ve both been around long enough to know how the Empire works. You know I’m right.’

Macro reached for his cup. ‘All this talk about politics has made me thirsty.’ He lifted the jug, but when he poured, only a thin trickle dribbled into his cup. ‘Shit . . . I’ll have to get some more from the kitchen.’

As he rose from his stool, Petronella cocked an ear towards the kitchen block at the far end of the courtyard. ‘What’s all that about?’

Macro frowned. Animated voices were coming from inside the building. ‘I’d better see to it.’

He trudged off, jug in hand, and disappeared inside. The others continued to listen as the exchange grew in volume, until it was suddenly cut off by the centurion demanding silence.

‘Sounds like trouble among the servants,’ Claudia commented.

Petronella shook her head. ‘They get on well. There’s two Iceni girls, and the stable lad is a local. Never heard a cross word between them. We’ll soon know what’s up when Macro comes back.’ As they waited, she changed the subject. ‘It’ll be Saturnalia soon. Will you still be living in Camulodunum then? You are welcome to join us.’

‘We’ll be here for a while yet,’ Cato answered. He had rented a modest villa at the colony. It overlooked the river and was south-facing to take advantage of what sun the province provided. There he and Claudia lived quietly while raising Lucius. The boy’s education was provided for by a man claiming to be a Greek scholar who had crossed from Gaul to set up a small school. His accent was not one that Cato had ever heard a Greek intone, but he was competent, and Lucius was learning to read and write and the basics of figure work. A more refined education awaited him in Rome, once Cato deemed it safe to return to the capital.

If any hint that Claudia had been traced to Britannia reached Londinium, it had been arranged that Apollonius would send them a warning. The Greek freedman had once served as a spy for Rome before he encountered Cato, and the two men regarded each other with respect if not friendship. Macro had disliked him from the first and treated him with suspicion, but Apollonius had won Cato’s trust and had now found himself a useful post at the Governor’s palace at Londinium.

‘It’s a peaceful backwater,’ Cato continued. ‘And that suits us.’

‘We’d be delighted to share Saturnalia with you.’ Claudia smiled. ‘You must tell me what we can contribute to the occasion.’

The sound of footsteps across the gravel interrupted the exchange, and they turned towards Macro. The centurion wore a concerned expression, and there was no freshly filled wine jug in his hands.

‘What’s happened?’ asked Cato.

‘Bad news, I’m afraid.’ Macro resumed his seat. ‘Morgatha’s just returned from the market. She encountered an Iceni fur-trader who’s come from the tribal capital. Prasutagus is dead.’

Cato shook his head sadly. Both he and Macro had known the Iceni king well. They had fought alongside him shortly after the invasion, when the tribe was a firm ally of Rome. His queen, Boudica, was also counted a close friend. The last time they had met, less than a year ago, Prasutagus had looked sickly, a distant shadow of the powerful warrior he had been in his prime.

‘There’s more,’ said Macro. ‘It seems he named Boudica and Nero as co-heirs in his will. I doubt that’s going to end well for the Iceni.’

‘Why is that?’ asked Claudia.

‘Nero doesn’t strike me as the kind who will settle for half of something when he can have all of it.’

‘Then surely this is a good thing for the province. It will give Nero a stronger stake in Britannia. More reason for him not to pull the legions out.’

‘Or he’ll just decide to loot the Iceni kingdom for all its worth and then abandon the island.’

Claudia turned to Cato. ‘What do you think?’

‘I’m not sure how this will play out,’ said Cato. ‘It’ll take time for word of the king’s death to reach Rome, then for Nero to reflect on what course of action to take and send the response to the governor in Londinium. If the weather is kind, Suetonius will receive his instructions early next year. About the same time as the renewal of the oaths. The Iceni contingent will be there along with the other tribes and representatives of the Roman settlements to swear their loyalty to the emperor and Rome. That’s when they’ll find out what Nero has decided.’

‘And what do you think he will decide?’ Claudia pressed him.

‘I suspect Macro’s right. The emperor will want it all, whatever Prasutagus’s will says. If that happens, there’ll be trouble. We know the Iceni.’ He nodded towards Macro. ‘They’re a proud lot with a strong sense of tradition. Fine warriors. We were lucky that they sided with us at the start, and lucky that it was only a handful of them who rose against us when Scapula was governor. If Nero plays this badly, he may provoke them into open rebellion. They’ll fight like lions to protect their lands, and I fear it will be a bloodbath.’

They had been tracking their prey all morning, and the noon sun hung low in the grey sky as flurries of snow blotted out the horizon. A short distance ahead of Macro and Cato was a Trinovantian hunter on foot, wearing a fur cape over his brown tunic and leggings. Cato was holding the bridle of his mount as they waited for him to inspect the ground. The hunter paused some thirty paces away and crouched as he examined a gap in the entanglement of gorse bushes that spread out on either side. There were many animal tracks in the snow fanning out from the gap, and it was hard to pick them apart and identify what creature might have made them.

‘We may have lost him,’ Macro muttered as he rested the thick shaft of the boar spear against the horns of his saddle and reached for his canteen. He took out the stopper, tilted his head and took a swig before offering it to Cato.

The prefect’s eyes were on the hunter, watching as the man scrutinised the disturbed snow. He took a sip and handed the canteen back before shifting his spear to his spare hand. ‘I don’t know. Pernocatus seems to be on to something.’

The hunter was tracing his fingers over the snow and then over the dark stem of the gorse bush to his right before he touched the surface delicately and then stared at his fingertip. He turned towards his Roman companions as he held up his hand so they could see the red smear.

‘Blood. The boar came through here,’ he announced in guttural Latin.

Pernocatus had hired himself out to Roman hunters ever since the colony was founded, and had picked up the invaders’ language well enough to speak it fluently. He was held in high regard amongst the veterans for his skills as a tracker, and when they closed in for the kill, his adeptness with spear and bow was as good as that of any bestiarius in the Empire.

The three-man hunting party had encountered the boar an hour or so after dawn, and there had been barely a chance to ready their spears before the beast charged through them and bolted. Cato had been lucky to land a glancing blow that had torn through its shoulder; not enough to cripple it, but enough to make it bleed and leave a trail to follow across the countryside. The blood spots had become less frequent as the wound had begun to clot, and they had almost given up when they had seen a handful of small splats in the snow close to the path leading to the gorse thicket. Cato was angry and frustrated with himself. It was the sign of a poor hunter to wound a creature and let it escape to suffer. He owed it to the animal to finish the job.

Macro indicated the thicket ahead of them. ‘Well, if the bastard’s in there, we can’t get close to him.’

Cato looked round. The gorse extended fifty paces on either side and looked to be as much across, beyond which rose the boughs of a copse of pine trees. The track through the dense mass was narrow. Reluctantly he agreed with his friend. There was no way they could ride through the thicket, and if they went on foot, they were bound to snag their cloaks and get caught up. If the boar charged them at that moment, there would be no chance to evade it. Still, there was one last trick they could attempt to provoke it.

‘Pernocatus, you stay here while the centurion and I ride round and see if we can find where the track comes out on the other side. If we locate it, I’ll call out to you. Then you make as much noise as you can. Use your horn. Beat the gorse. If the boar makes a run for it, we’ll be waiting for him.’

The hunter tilted his head to the side doubtfully, but nodded. ‘As the prefect commands.’

There was something in his tone that struck Cato as being slightly off, a hint of obsequiousness that was uncharacteristic, and he feared that he had offended the man with the brusqueness of his order. Sometimes it was hard to take the soldier out of the man, he mused regretfully.

‘Let’s get moving,’ said Macro, lifting his spear and holding the shaft out to the side. ‘Before he gets the frights and bolts.’ He urged his mount into a trot and rode off around the line of gorse. Cato handed the reins of the hunter’s horse to Pernocatus with a nod and cantered off after his friend.

As he had anticipated, the thicket was not large, and there was a clear gap between the far side and the pine trees. They found the place where the trail left the thicket easily enough, but leaning from his saddle, Cato saw no sign of blood.

‘He’s still in there.’

The two Romans scanned the tangled undergrowth for movement or sound that might indicate the presence of the boar, but there was nothing. Cato readied his spear and Macro followed suit, then they took up position each side of the trail.

‘Ready?’ asked Cato.

Macro nodded.

‘Pernocatus!’ Cato called out. ‘Begin!’

The strident note of the hunter’s horn cut through the cold air. The sound startled some birds, who burst from cover with a shrill chorus of panicked tweets, wings moving furiously as they fled towards the pine trees and disappeared. After a few more blasts of the horn, the hunter began to shout, and Cato could make out the faint crackle and snap of twigs breaking as they were beaten on the far side. Then they heard it, the snort and throaty squeal from somewhere between themselves and Pernocatus. A moment later, there was the rustle of dry vegetation as the boar drove towards them, charging down the trail.

‘Here he comes!’ Macro shouted, his eyes wide with excitement as he lowered the broad iron blade of his spear and held the shaft poised to strike. Cato did the same, keeping a firm grip of his reins and clenching his thighs against the saddle.

The boar burst out of the thicket and both men spurred forward. It was a huge, shaggy beast with a darker line of bristles growing along its spine towards its large head, where curved tusks protruded either side of the snout. Macro was faster to react, and he leaned forward and lunged, the point of his spear driving into the boar’s flank. The beast’s jaws parted as it uttered a pained cry, then it swerved away from the spearhead, in towards Macro’s mount, and collided with the pony’s hind legs. Macro swayed, forced to drop his spear as he snatched at the saddle horns and held on tight to avoid being thrown off. His pony staggered in between the enraged boar and Cato, blocking the target for his friend.

‘Shit!’ Cato hissed through gritted teeth as he pulled hard on the reins and tried to work his own mount round to strike at the beast. Before he could get a clear sight, however, the boar turned and rushed back into the gorse, tearing along the narrow trail in the direction of Pernocatus. At once Cato grasped the danger facing the other man, and quickly turned to Macro. ‘Get your spear and follow me!’

Without waiting for a reply, he urged his pony into a gallop along the edge of the thicket, the blood pounding in his ears. There was always a risk in hunting, particularly with prey as deadly as wild boar, and that was why only the most reckless faced such a beast alone. As he steered his mount around the spiky tangles of gorse, he heard Pernocatus cry out in alarm.

‘He’s here!’

Swerving round an outlying clump of bushes, Cato caught sight of the hunter a hundred paces away. He was on foot and facing the boar, a dagger in his hand. The beast, flanks heaving with exertion and surrounded by swirls of exhaled breath, stood between Pernocatus and his mount. As Cato kicked his heels in to force his pony to increase its pace, he saw the boar charge, kicking up gouts of snow as it sped towards Pernocatus. The hunter’s pony reared in panic and turned to flee. Pernocatus lowered himself into a crouch and held his position until the last instant before throwing himself aside and slashing at the boar as it swept past. Despite its bulk, some five feet in length and as high as a man’s midriff, the beast was nimble, and it slith

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...