- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

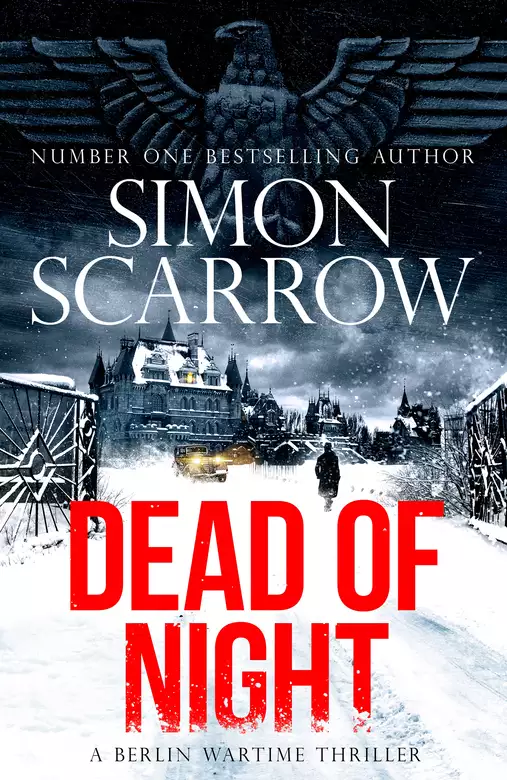

The stunning new thriller set in wartime Berlin from the author of Blackout.

BERLIN. JANUARY 1941. Evil cannot bring about good . . .

After Germany's invasion of Poland, the world is holding its breath and hoping for peace. At home, the Nazi Party's hold on power is absolute.

One freezing night, an SS doctor and his wife return from an evening mingling with their fellow Nazis at the concert hall. By the time the sun rises, the doctor will be lying lifeless in a pool of blood.

Was it murder or suicide? Criminal Inspector Horst Schenke is told that under no circumstances should he investigate. The doctor's widow, however, is convinced her husband was the target of a hit. But why would anyone murder an apparently obscure doctor? Compelled to dig deeper, Schenke learns of the mysterious death of a child. The cases seem unconnected, but soon chilling links begin to emerge that point to a terrifying secret.

Even in times of war, under a ruthless regime, there are places in hell no man should ever enter. And Schenke fears he may not return alive . . .

Rave reviews for BLACKOUT - Simon Scarrow's first Berlin Wartime Thriller

'Taut and chilling - I was completely gripped' Anthony Horowitz

'A terrific depiction of the human world within the chilling world of the Third Reich' Peter James

'Mesmerising. Nail-biting. Unputdownable' Damien Lewis

(P) 2023 Headline Publishing Group Ltd

Release date: December 26, 2023

Publisher: Kensington Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dead of Night

Simon Scarrow

PrologueBerlin, 28 January 1940

The choir and orchestra reached the end of the reprise of ‘Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi’, and with a final sweep of his baton the conductor brought the performance to an end, bowing his head as if in exhaustion. At once the audience at the Philharmonie let out a cheer and applause thundered through the hall. As the conductor turned, some of the audience rose to offer a standing ovation and the rest began to follow.

Dr Manfred Schmesler sighed as he stood stiffly. Like those around him, he was wearing his overcoat and gloves but no hat, so that he might hear the music more easily despite the cold. Because of the shortage of coal in the city, the heating had not been turned on, and even after an hour and a half of the audience crowding into the hall, the air was frigid. Schmesler wondered how the performers had been able to carry on in such conditions. Perhaps the need to concentrate had distracted them from the icy atmosphere.

He felt a light pressure on his arm and turned to his wife, Brigitte. She said something inaudible, then cleared her throat and spoke loudly as he dipped his ear towards her.

‘I said, they did wonderfully.’

‘Yes,’ he replied. ‘Under the circumstances.’

The applause continued as Wilhelm Furtwängler gestured to his orchestra to take a bow, and then the choir. The clapping subsided and there was the usual bustle as the crowd edged towards the aisles and made for the exits. Schmesler guided his wife out, along with the couple who had accompanied them to the performance, Hans Eberman, a lawyer, and his wife, Eva. The Schmeslers had met the Ebermans at a party a few months earlier, and had shared a number of social events since then.

Eberman caught his eye and commented just loudly enough to be heard, ‘How fortunate that the tickets were free.’

Schmesler knew his companion well enough to sense the irony, and smiled back briefly. Since the Nazi Party had taken power, they had driven a host of musicians and composers into exile and limited the repertoire of those that remained to mainly German music, which meant the capital’s concerts were becoming repetitive. At least they had been spared an evening of Wagner, thought Schmesler.

As the crowd edged forward, people fumbled for scarves and mufflers and put on their hats in preparation for the cold out in the street. Berlin was in the grip of the bitterest winter in living memory: the canals and the River Spree were frozen over, and snow covered the city. And the nation was at war again. Schmesler was old enough to have served in the previous conflict, and his memory was scarred by the terrible suffering he had witnessed on the Western Front. The war to end all wars, they had called it, and yet scarcely twenty years later, war had returned to Germany. And with it had come food rationing and the nightly blackout that smothered Berlin with darkness once the sun set.

The increasing scarcity of coal meant that heating was a luxury for the few, mostly senior members of the Nazi Party or their cronies. Although Schmesler was a member, he had joined as part of the wave of professionals who had seen the way things were going and realised that membership would become the sine qua non of any successful career, as well as serving a more private purpose. And so it had proved for doctors and for lawyers like his new friend Eberman. Those who had joined the party in the days of the Weimar Republic looked down on the newcomers with contempt for their new-found enthusiasm for the cause. More importantly, they were not inclined to share their supply of coal.

It was strange, Schmesler reflected, that a resource once so commonplace was now a rare and valuable commodity. Even the coal that did turn up in the capital tended to be the degassed variety, lacking the greasy sheen of the better-quality type that generated more heat. He and Brigitte were obliged to burn wood in the stoves of their house in Pankow to stay warm and heat enough water to wash with. The boiler that supplied the building was only fired up at weekends and on Tuesday and Thursday evenings, when coal supplies allowed. Even wood was becoming scarce, and Schmesler prayed for the prolonged spell of freezing weather to end.

As they approached the exit into the foyer, he heard a harsh voice cut

through the hubbub of conversation.

‘Winter Aid! Winter Aid collection!’

He saw four men in greatcoats with the brown caps of the party paramilitaries. One had raised a tin and rattled it loudly before he repeated his cry.

‘Damn them,’ Eberman muttered. ‘Don’t they fleece us enough already with their bloody collections?’

Schmesler reached into his coat pocket and took out a handful of badges. Poking through them, he found the special Winter Aid badges he had earned through previous donations. He handed one to Eberman before fixing his own to his lapel, where it would be seen. His companion smiled at the thought of getting one over on the party’s henchmen clustered about the exits, where they intimidated those passing into handing over money for the cause. A visitor to Berlin might think this was charity, whereas the inhabitants recognised it for what it was – one step short of being mugged.

A man blocked the way of the group ahead of Schmesler and his lips curled in amusement. ‘Spare some change to help those in need, friend.’

There was no trace of a polite request, merely an instruction, and the concert-leavers without donor badges paid up and hurried away. An SA man stepped in front of Schmesler and held up his tin.

‘Winter Aid.’

Schmesler angled his shoulder slightly to display the badge, and the SA man waved the two couples past before confronting those behind them. Schmesler took his wife’s arm and increased their pace as they passed through the foyer and out of the revolving door onto the pavement. At once the freezing night air bit at their exposed skin, and they hunched their heads into their collars and breathed swirls of steam.

Eberman made to return his badge, but Schmesler shook his head. ‘Keep it. Who knows how many more SA parties are on the streets tonight.’

‘Thanks.’

Despite the blackout, there was enough illumination from the narrow beams of masked car headlights and the loom of mounds of snow for them to see their way, and Schmesler led them along the street towards the U-Bahn station. Once he was clear of the crowd emerging from the theatre, he slowed so that the other couple could fall into step beside him and Brigitte. The trampled snow had compacted into ice, and she clung to his arm to avoid slipping. The conditions

discouraged any further conversation until they reached the steps to the station, where they would part company; Schmesler and his wife catching a train to Pankow while the Ebermans walked the remaining distance to their apartment on the next street.

‘Shall we go to the Richard Strauss event next Friday?’ asked Eva.

Her husband sniffed. ‘Not that there’s much of a choice these days.’

She swatted his shoulder. ‘Strauss may not be the kind of first-class composer you are so fond of, but at least he’s a first-rate second-class composer.’

All four laughed knowingly before Eberman continued, ‘It seems that no piece of German music should be so sophisticated that it could not be belted out at a Nazi Party rally, eh?’

‘Come now,’ said Schmesler. ‘It’s music all the same, and it’s a pleasant distraction from the war. It’ll be good for us.’

‘I suppose . . .’

‘Then it’s settled. And it’s your turn to get the tickets, my friend.’

Schmesler glanced towards the station entrance at the sound of an approaching train. ‘We have to go.’ He turned back to his companion. ‘Are we still meeting for lunch next Monday? About that matter you wanted to discuss?’

Eberman shook his head. ‘It’s not important any more. Another time perhaps.’

There were handshakes and farewells as the couples parted, the Schmeslers hurrying down the stairs into the station. They reached the platform just as the northbound train pulled in. Doors clattered open and shut as passengers alighted or boarded; the guard blew his whistle. The train jolted into motion and Schmesler and his wife nearly lost their balance as they made for an empty space on one of the benches. It reminded them both of an evening when Schmesler had invited Brigitte out after they’d first met. The motion of the train had thrown them against each other and he had instinctively put his arm around her to stop her from falling. It had broken the ice and they had laughed nervously. Now they smiled at each other in delight at the unbidden memory of that night.

Conversation was difficult on the U-Bahn trains, and in recent years people tended to be careful of what they said in case an inadvertent comment attracted the attention of an informer. The two of them held hands and sat in silence, counting off the stops until the train pulled into their station in the Pankow district. Stepping out of the carriage, they walked quickly through the cold, dark streets of the smart residential neighbourhood until they reached their home.

It was a modest two-storey building dating from the middle of the last century. Schmesler had acquired it three years earlier from its Jewish owners, the Frankels. He had studied at Berlin University with Josef Frankel, and they had once been close friends. After the Nazis had come to power, the friendship was no longer advisable and they had kept their distance, socialising in secret. With Frankel no

longer able to operate his business, he had left Germany with his family as restrictions tightened around the country’s Jewish community. He had sold his house to his good friend Schmesler for a bargain price, and taken what little capital he had in order to make a new life in New York. However, the family had been forced to leave behind a younger daughter, Ruth, when they had failed to find her birth certificate, and now that war had broken out, she was trapped in Berlin.

The couple climbed the steps from the street and scraped the snow from their shoes on the iron bar next to the covered porch. Schmesler unlocked the front door, and they stepped inside and closed it before turning on the lights, so as not to provide an excuse for the local block warden to fine them for breaching blackout regulations.

It was cold enough indoors to require them to keep their coats and gloves on, and only their hats were hung on the stand beside the door. Schmesler kissed his wife on the forehead.

‘You go on up to bed. I’ll be along a bit later.’

‘Work?’ She sighed.

He nodded. ‘We’re short-handed at the centre, thanks to conscription.’

‘Did they have to take all your assistants?’

‘In time of war, the army needs all the doctors it can find, my love.’

Brigitte shook her head. ‘War . . . So much for the Führer’s claim of being a man of peace.’

Schmesler instinctively glanced round before he could catch himself, and smiled guiltily as he responded. ‘Make sure such words stay at home. Be careful who you share your doubts with.’

‘I would hope I’d be safe speaking my mind to my husband of twenty years.’

He winked at her. ‘You never know . . .’

‘Oh, you!’ She pinched his cheek.

‘Give the Führer a chance, Brigitte. Now that Poland is obliterated, there is no reason for France or Britain to continue the war. We may have peace by the time spring comes. Hold on to that hope, eh? Now, to bed with you, before I tell the Gestapo you are sharing un-German propaganda.’

He watched as she climbed the stairs to the galleried landing, turned on the light and disappeared from view. Then, making his way to the parlour, he sat in the chair in front of the stove and opened the hatch. The heavy iron was still warm, even through the thickness of his gloves, and he saw a dim glow within. When he opened the vent, the heat intensified and smoke curled up. Taking some kindling, he arranged it over the first small flames to flicker into life. He waited until there was a healthy blaze before he added some split logs and shut the hatch. Already he could feel the warmth radiating from the ironwork, and he let it seep into his body, smiling with contentment.

He glanced at the desk beneath the blackout curtains. There was a briefcase sitting there that contained a folder of reports awaiting his attention. He had been putting off the moment all day at the office, and now again at home. It could be delayed no longer. He eased himself to his feet and crossed to the small side table where he kept a decanter of brandy and some glasses, and poured himself a generous measure. Then, settling in the leather desk chair with the warmth of the fire at his back, he opened the case and took out the file. Reaching for a pen, he flicked open the cover and glanced over the first report, considering the hand-written recommendation at the bottom. His right hand moved, and the nib hovered over the report. He hesitated, then knocked the brandy back, feeling the fiery liquid surge down his throat. Setting the glass down with a rap, he marked the final box on the page with a ‘+’, moved the sheet to the side and considered the next document.

The clock on the mantelpiece marked the passage of time with a steady tick tock. Every so often, Schmesler stirred to place another log in the stove as he worked late into the night processing the documents into two piles: one for those marked in the same way that the first report had been, and a smaller pile where he had left the box empty and merely signed the report instead.

Upstairs, his wife slept alone in her thick nightdress beneath several layers of covers. She lay on her side, breathing deeply, sleeping in a dreamless and untroubled state until the early hours of the morning, when a sharp crack sounded from downstairs and jolted her awake. For a few heartbeats she was not sure if she had imagined the sound. She reached under the covers to where her husband usually lay, but he was not there, and the bedding was cold and clammy. She waited for several minutes, listening for further sounds before she stirred. Turning on the bedside lamp, she squinted at the sudden brightness as she looked at the alarm clock. Just past three o’clock. An absurd hour for her husband to still be working.

She swung her legs from under the covers and slid her feet into her slippers before making for the top of the stairs.

‘Manfred,’ she called out. ‘Manfred . . .’

She waited for a response, but there was silence, and she tutted irritably as she descended the stairs and made for his study. As she opened the door, warm air washed over her, and with it came the acrid odour of gun smoke.

‘Manfred . . . ?’

She did not see her husband immediately. There were papers scattered across the desk and on the floor nearby. The chair lay on its side, and an outstretched arm projected from behind it. A short distance from the curled fingers of the hand lay the dark shape of a pistol.

31 January

It was shortly after midday when the door to the Kripo section office opened. Sergeant Hauser looked up as a man in a dark coat hung his hat on the stand inside the entrance. He crossed to the stove in the center of the room and turned to warm his back before nodding a greeting. The sergeant was doing his best to write up some notes while recovering from a gunshot wound to his shoulder. Although it had been a flesh wound, he still wore a sling from time to time when he needed to ease what remained of the pain. Now he set his pen down.

“How did it go, sir?”

His superior, Criminal Inspector Horst Schenke, had attended a funeral that morning. Count Anton Harstein and his wife, an elderly couple who had been family friends, had been murdered shortly before Christmas. Thanks to the paperwork associated with the investigation and the delay caused by frozen soil, it had taken five weeks before the bodies could be buried. Count Harstein had once managed the Silver Arrows motor racing team that Schenke had driven for before a crash had ended his racing career and left him with a limp. After the accident, Schenke had needed a new direction in life and had joined the police.

He took a deep breath. “As well as such things can.” Despite the Harsteins being aristocratic and well connected, few mourners had turned up to the funeral. Apart from Schenke and his girlfriend, Karin, there had been no more than ten others, including the Harsteins’ son, an army officer who had been given compassionate leave to attend. The bitter winter had kept away most of those who might otherwise have been there, and the priest had stumbled through the service with chattering teeth, somewhat faster than was decent. The murders had cast a pall over what little Christmas cheer there had been, and Schenke was still grieving for them in his private moments. He did not want to give his feelings away.

“How’s the wound healing?” he asked Hauser.

“Slowly enough to save me from household chores.” Hauser grinned. “Helga’s starting to get suspicious, though, so I’m having to show some signs of recovery.”

“You live dangerously, my friend.” Schenke had only met Hauser’s wife on a handful of occasions, but that was more than enough to realize that she was formidable. “Even without being shot at.”

Both men were quiet for a moment as they recalled the incident at the Abwehr headquarters where Hauser had taken a bullet, then the sergeant turned to a thin man in his midtwenties sitting at another desk. He had fine white hair over a gaunt, bespectacled face, and unlike the others he wore no coat but sat in a simple dark suit and tie, apparently oblivious to the cold. He was reading the front page of the Völkischer Beobachter newspaper. The headline story concerned the gallant resistance of the Finnish army as it held back the Russian invasion and defied the ill-equipped and incompetent legions of Stalin. Even though a pact had been signed with Russia the previous August, the article was clearly sympathetic to the Finns. Russia put in its place, the headline ran. Schenke wondered how long such a treaty could endure between two nations with such diametrically opposed ideologies? It was odd, Schenke thought, that a very real war was taking place with high numbers of casualties—at least on the Russian side—while the land war Germany was involved in seemed to be little more than an occasional exchange of shots and the dropping of propaganda leaflets since the fall of Poland. Although, like many people, he still hoped for a peaceful resolution, he was beginning to fear that worse was to come.

“Liebwitz, go and see if the man from the lab has finished examining those ration coupons that came in this morning.”

“Yes, Sergeant.” Liebwitz rose quickly and gave a nod before he strode out of the office.

Schenke felt a stab of guilt. Liebwitz had been sent to the Kripo section to assist with the investigation into the killings before Christmas. Recruited into the Gestapo, his stiffly formal attitude had not endeared him to his colleagues, and Schenke suspected that he had been assigned to the Kripo to get him out of the way. Now he was waiting for official confirmation that his transfer was permanent. The wheels of bureaucracy were turning at their usual glacial pace, so for the moment, Liebwitz was still officially Gestapo, and that made him a target for Hauser, who treated him as the office dogsbody.

“You could go easy on him,” Schenke said.

“He has to pay his dues, like any member of the team.”

“He has nothing to prove. He’s done a good job.”

“So far . . .”

Schenke could see that he was not going to shift the sergeant’s feelings towards the new man and looked round the office at the empty desks. “Where are the rest of the team this morning?”

“Frieda and Rosa are interviewing a woman about a domestic assault. Persinger and Hofer are out rounding up a few of the known forgers and fences for interrogation about the fake ration coupons. One of them must know something about it.”

Schenke nodded. Persinger and Hofer were veterans of the police force. Both were big men who had a talent for getting information out of suspects, even without having to resort to violence. There was a no-nonsense demeanor about them that was usefully intimidating. Frieda Echs was in her forties, solid and efficient, with enough lived experience to handle situations sensitively. The section’s other woman, Rosa Mayer, was slim, blonde and striking, and was good at her job and at fending off attempts to flirt with her.

“Schmidt and Baumer are down at the Alex attending a political education seminar.”

“I’m sure that will broaden their minds,” Schenke responded quietly as he considered the political training sessions held at the Alexanderplatz police headquarters. Schmidt and Baumer had joined the force since the Nazis had seized power, and were therefore deemed more likely to be responsive to the regime’s propaganda. Hence their summons to the seminar. Even so, Schenke had sufficient faith in their intelligence and detective training that he was confident they would privately question what they were told. Even though Hauser was a party member, the sergeant similarly had little time for some of the activities of the Nazi Party. The notion that there was an “Aryan way” of conducting criminal investigations struck both men as a ridiculous waste of time.

“I dare say we’ll be sent for political training at some point.”

Hauser shrugged. “No doubt. In the meantime, let’s just do the job, eh, sir?”

There was a subtle warning in the retort to remind Schenke that the occasional critical comment about the party was acceptable but not to push the issue.

The door opened, and both men turned to see Liebwitz holding it ajar to admit an overweight man with a sour expression. He wore an unbuttoned coat over his suit and swept the folds aside to stuff his hands in his pockets. While Liebwitz hurried past him to his desk, the visitor glanced at the two Kripo men by the stove and fixed his eyes on Hauser.

“Inspector?”

The sergeant pointed at his superior. “Try him.”

The man shifted his gaze. “Doctor Albert Widmann, from Chemistry Analysis at the Werdescher Labs.” He didn’t offer a handshake.

“Criminal Inspector Horst Schenke. You’ve had a good look at the latest batch of coupons we seized. What do you make of them?”

Widmann collected his thoughts. “They’re good. Easy to take for the real thing, to the unpracticed eye. For an expert like myself, of course, the forgeries are obvious to detect.”

“Oh?” Hauser arched an eyebrow. “How so? From an expert’s point of view, of course.”

Widmann puffed his chest out slightly. “Certain irregularities on the perforations, for example. You wouldn’t notice if you were presented with a single coupon, but it’s clear to see when you have a sheet of them in front of you.”

“How do they compare with the others we already have?” asked Schenke. “Do they come from the same source?”

“From first inspection, I’d say so, but I’ll have to take them back to the lab to test the composition of the dyes and the paper before I can confirm that. Do you suspect they are the work of one man, or one crime ring?”

“We don’t know. It’s a possibility.”

“If so, it should make them easier to track down.”

Schenke shared an amused glance with Hauser, and Widmann frowned.

“What?”

“If it’s the work of one crime ring, then we’re dealing with a sizeable organization. One that’s managed not only to avoid the previous round-ups but is sufficiently well hidden from police eyes that we haven’t encountered them yet. If it’s more than one ring, there’s a chance we’ll already know about some of them and we can use our informers to uncover the links between them.”

Widmann nodded. “I see. Very good. Makes sense.”

Hauser cleared his throat. “Perhaps you should spend some time with us. Be good for you to see how Kripo does its work out on the streets.”

“In this weather?” Widmann said. “Fuck that. I’ll stick to my nice warm lab, thank you.”

All three shared a brief laugh before Widmann buttoned his coat. “I’ll fetch those samples and be on my way.”

“Let us know the results as soon as you can,” said Schenke.

“You’re not the only investigators calling on my time. I’ve a few other jobs to do first.”

Schenke stepped between Widmann and the door. “If we don’t put a stop to these forgers, many people will have to go without food this winter. I’m not sure how sympathetic starving people are going to be about your priorities. And if the people are unhappy and that gets back to Heydrich’s office, I doubt he’ll be sympathetic either. What do you say, Liebwitz? You’re a Gestapo man. You’re better placed to know how the Gruppenführer will react.”

Liebwitz looked up from his paperwork with his usual deadpan expression. “I think he would be displeased to hear of any dissatisfaction amongst the people, sir.”

At the mention of the name of the director of the Reich Security Main Office, Widmann’s eyes widened. He swallowed nervously.

“I’ll see what I can do.”

Schenke smiled. “I’m sure you will. Thanks.”

Once the scientist had closed the door behind him, Schenke turned to Liebwitz with a grin. “Couldn’t have done a better job myself of putting the shits up him.”

“I merely expressed the truth, sir. Heydrich pays close attention to the social intelligence reports. I have seen his response to those he does not like at first hand.”

Schenke was not yet certain how much the new team member’s attitude was down to dedicated professionalism and how much was due to defective social skills.

“Of course you have,” he responded, and then glanced at his watch. “I’m going out for some lunch. If Persinger and Hofer get back before I do, tell them to start the interrogations without me.”

Hauser nodded, and the inspector turned to leave, pulling up his collar in readiness for the bitter cold of the street.

Even though the snowfall had been fitful since New Year, the streets had not yet been cleared. Stained mounds lined the pavements, shoulder-high in places, with gaps left at crossing points. Grit had been laid on the paths and gave the icy surface a dirty speckled appearance. Despite the cold, there were plenty of people out, moving quickly, chins down as they left trails of breath in their wake. Those buildings lucky enough to have regular heating were betrayed by the absence of snow on their roof tiles, and Schenke noted the bare roof of the local party office. An SA man was outside, pasting a replacement over a blackout poster that had been defaced by a brush moustache and a lick of dark hair over the forehead of the skeletal head of death as it rode a bomb dropped by a British plane.

The SA man glanced round, and for a moment Schenke feared he would raise his arm in the “German greeting,” which would oblige Schenke to remove his hand from his pocket to do the same. But the man glanced at the pasting brush in his right hand and rolled his eyes instead, and Schenke smiled as he strode by.

At the end of the street, he turned left into a working-class neighborhood where there were a number of traditional beer cellars and cafés. He crossed the street and made for the entrance of Wehler’s, where it was still possible to buy coffee. The bell above the door clanged as he entered and closed it quickly behind him. A warm fug of smoky air filled a large space packed with tables and chairs. A counter ran the length of the rear of the café, and the mirrors mounted on the wall behind it made the place feel twice as large.

Wehler’s was popular with those taking a midday meal, but Schenke was able to find himself a seat in a cozy booth beside a window overlooking the street. He unbuttoned his coat and loosened his scarf as he waited for one of the waiters to come over. The condensation on the inside of the window made it impossible to see out clearly, and those passing by were only visible as dark blurs. So it was that he missed the figure who had followed him from the precinct and now stood hesitantly on the far side of the street.

His mind played over Widmann’s comments about the forged ration coupons. If it was the case that they were dealing with a previously unknown crime ring, then their prey was going to be difficult to track down. One thing the Nazi regime had achieved was the rounding-up of most of Berlin’s criminal organizations and the execution or imprisonment of their members. In the frequent absence of legal niceties such as evidence and due process, such measures had succeeded in reducing organized crime, though the crimes of individuals continued: theft, fraud, assault, mugging, rape and murder. Whatever regime was in power, such crimes would always live alongside humanity. He forced his mind away from work and thought about Karin instead. They had arranged to watch the latest film starring Heinrich George at the local Ufa cinema that night. He was looking forward to seeing her.

A woman lowered herself onto the bench on the other side of the booth. Schenke glanced up with a polite smile, ready to welcome any companion for lunch. Then his smile froze as he saw her face, and he felt an icy prickle of anxiety grip the back of his neck.

Ruth Frankel was slight and wore a threadbare brown coat. The seam on one of her gloves was pulling apart and her face looked pale, even for a Berliner in the middle of winter. Her dark eyes regarded him nervously beneath fine eyebrows and a widow’s peak of dark curly hair that fell beneath the brim of her felt hat.

“Hello, Horst.” She forced a smile. “How are you?”

Schenke glanced round the café, but no one seemed to be looking in their direction or paying them attention. He spoke quietly. “What are you doing here?”

“I need to speak to you. There’s no one else who can help me.”

He leaned forward. “What do you want? Money?”

She frowned slightly and shook her head. “That’s not why I’m here. Why would you think that, I wonder? Wouldn’t have anything to do with all those posters and newspaper smears about money-grabbing Jews the party is so fond of printing? You think I’d risk trying to blackmail you? Is that it?”

Schenke inhaled deeply to calm himself. “I’m sorry, Ruth. But you know the danger we both face if anyone realizes what you are and informs on us.”

Her expression became frigid. “You make me sound like a thing rather than a person. Is that what I am to you?”

Schenke was stung by her comment, then felt guilty. Ruth had been instrumental in catching the killer who had been using the blackout to murder women in the last months of the previous year. She had nearly been a victim herself, and had she not fought off her attacker and provided crucial information to Schenke and his team, the killer would still be at large. In the brief time he had known her, he had felt pity, and guilt, for her predicament. If they had lived in another Germany, she would be someone he would be keen to know better.

“I didn’t think I’d see you again.”

She smiled sadly. “I had no intention of seeing you either. I wanted to disappear into the shadows and stay out of sight as much as possible, long enough for people to forget my face in the newspapers. That was your doing, remember.”

“I had no choice. The orders came from the head of the Gestapo.”

“So you say.”

A waiter was heading towards them, and Schenke beckoned to him while Ruth sat back and pretended to rummage in her handbag as if looking for something.

He nodded a greeting to the man. “I’ll have the soup of the day and coffee.”

“No coffee, sir. We have a substitute, if that will do?” Schenke recoiled at the thought of the bitter ersatz coffee. “Tea, then.”

“Very good, sir. And what will the lady have?”

Schenke was taken aback by the question. He had not intended to share a meal with Ruth and had hoped that she might be persuaded to speak her piece and leave him alone as swiftly as possible. Every moment he spent in her company endangered them, her most of all. Any Jew caught consorting with an Aryan in a public place was likely to be sent to a work camp, from where she would not return. Schenke would be kicked out of the police and imprisoned for several months before being released to scratch a living on the margins of society. They must bluff it out now and act as if this was a normal, and lawful, lunch date.

“I’ll have the same,” said Ruth.

“Very good.” The waiter turned to make his way back through the café. They would be left alone for a while, and Schenke folded his arms to make it clear to anyone watching that they were not a couple. Even so, he saw from her pinched, pale face that Ruth could use a decent meal, and he felt an urge to help her.

“What is this about?” he asked in a gentle tone. “You said you needed my help. Why me particularly?”

“Because you’re a policeman.”

“I’d have thought that was the very last kind of person you’d turn to.”

“In any other circumstances, yes. But I know you, Horst. I know you are a good man who wants to do what is right.”

“I want to uphold the law and bring to justice those who break it. That’s all.”

She gave him a knowing look. “That’s what you might tell others. You don’t have to spin me that line. I know you have more integrity than most. And compassion.”

It was pointless to refute her observation and pretend that a hard heart dwelled beneath the professional veneer he tried to cultivate. He had treated her with some kindness and consideration during the murder investigation; at the very least he had shown her sympathy. He was tempted to feel more for her, and quickly stifled the impulse.

“All right. I will hear you out, but I can’t promise to do more than that. Even if I want to.”

“I understand.” Ruth paused and looked down at her gloved hands as she collected her thoughts. “I’m here on behalf of a family friend. A good friend. She lost her husband a few days back. You may have heard about it. His name was Manfred Schmesler.”

“Schmesler?” Schenke searched his memory and recalled a brief obituary in the Völkischer Beobachter. “Yes, I saw the report. A doctor, as I recall. He lived in Pankow.”

“An SS Reich doctor,” said Ruth, and he saw the flicker of distaste on her face. “But he was a family friend long before he joined the SS, and the party. He was close friends with my father when they were at university, and they remained close until that was no longer possible. But they stayed in contact, being careful that it was done in secret. Schmesler and his wife supplied us with extra rations and money from time to time.” She paused. “Needless to say, I trust you not to repeat any of this. I would not want his widow to get into trouble. She already has enough to cope with without falling foul of the police or the Gestapo.”

“I understand. Go on.”

“Although the newspapers do not give the details of his death, the official version is that Manfred Schmesler committed suicide. That’s what the police concluded after they were called to the scene. His widow is adamant that he would never have killed himself. He was under pressure at work, but he enjoyed life and loved his wife.” There was something in the tone of her voice when she said “wife” that struck Schenke as odd.

“That’s how it appears sometimes,” he said, “but people can hide their true feelings well enough for their family to be unaware. Did he leave a note?”

“Yes,” Ruth conceded.

“So?”

“His wife says she can’t believe that it can be true.”

“What does it say?”

Ruth shook her head. “I don’t know. She was too upset to tell me. Only that he had never given any indication that he was ashamed of his work and did not deserve to live. She is certain that he did not die by his own hand.”

“Murder?” Schenke frowned. “How did it happen?”

“He was shot through the head. She discovered him in his study with a gun close to his hand.”

“His own gun?”

Ruth nodded.

“And the note was where?”

“On the desk.”

“Written in his hand?”

Ruth thought a moment and nodded. “That’s what Brigitte, his wife . . . widow says.”

“I have to say that on the face of it, the death could well be a suicide.”

They were interrupted by the return of the waiter carrying a tray bearing two steaming bowls, two teacups on saucers and a teapot. He set them on the table, along with spoons, and withdrew. Schenke made sure the man was out of earshot before he spoke.

“Where do I feature in this situation?”

“Brigitte Schmesler wants you to look into her husband’s death and say whether you think it was really suicide. She knows that I helped you find the man responsible for killing those women last year. I told her you were a good man. She thought her request would be better coming from someone you know personally. So I agreed to approach you.”

Schenke nodded slowly as he stared across the table. “You’re taking a big risk on behalf of someone you say is a family friend,” he prompted, but her expression remained fixed, so he continued. “If the police have concluded it was suicide, they must have their reasons.”

“Brigitte is convinced they are wrong.”

Schenke realized that it would look strange if they neglected their meal, so he picked up his spoon and sipped his soup cautiously. Ruth did the same. Both were silent for a while as he thought over what she had told him. If there had been any doubt about Schmesler’s death, the matter would have been referred to Schenke’s section at the Pankow precinct. Clearly the regular police, the Orpo, were content that it was a suicide. That was a rush to judgment that struck him as unusual, given Brigitte Schmesler’s conviction that her husband had not taken his own life. Even with all the disruption caused by the war and the shortage of men due to conscription, someone should have referred the case to the Kripo. The fact that the Orpo had decided that no further inquiry into the death was required made it difficult for him to raise the matter without giving an explanation for his interest. All the same, he hoped it would not ruffle too many feathers if he merely asked a few questions. Enough to persuade Brigitte that it was suicide after all.

But what if she was right? Or at least, what if the answers were not sufficiently convincing? What then? With the investigation into the forged ration coupons taking up nearly all Schenke’s time, any new investigation would be an extra burden. However, if it hadn’t been for Ruth, it was likely that the police would still be hunting for the killer stalking the capital’s railway system before Christmas. He owed her a favor.

“What are you thinking?” She was staring at him. “Will you look into it?”

“And what if I think it is suicide? Will you let the matter go?”

She nodded. “I’ve risked enough just to approach you. If you tell me you think the official decision is correct, I’ll inform Brigitte and leave you alone. But I can’t answer for what she may do.”

“Fair enough. I’ll see what I can find out. Give me two days.”

“Shall I meet you here?”

“I’d rather not. It’s not safe for you. There’s a newspaper kiosk outside the U-Bahn station. We’ll meet there at noon. It won’t take long, either way.”

She glanced down at her soup hungrily, and Schenke realized she had been counting on another meal. “All right, we’ll meet here. Just make sure you aren’t being watched. If I see anyone following you, we’ll meet at the kiosk the next day. Agreed?”

Ruth nodded. “Thank you.”

They ate in silence and mopped up the dregs of their soup with the dark bread before Schenke sat back and regarded her sympathetically. “How are you coping? Still living with the old woman who took you in?”

“She kicked me out as soon as she heard I’d been involved with the police.”

“Where did you go?”

“A friend let me stay with her for a few days,” she replied with a guarded expression.

“You have nothing to fear from me,” said Schenke. “I have no interest in the comings and goings of you or your people. I have bigger fish to fry.”

She picked up her cup and drank some tea. “And what happens when the Jews become the bigger fish?”

“Hopefully that won’t be my problem.”

“But it will be mine. And if your superiors make it yours? Would you hunt me down if you were ordered to?”

Schenke considered the question briefly. “Only if you had committed the kind of crime that falls within the usual remit of the Kripo. Otherwise, no. I’d find a way to leave you be.”

“I hope I never have to hold you to that, Horst. But with the way things are going, the outlook for the Jews is bleak. From the rumors I hear, the Polish are being treated like animals by your masters. If that is the case, what hope have my people got?”

“What will you do?”

“If the time comes when the party decides to remove the Jews, I have a plan.”

“You won’t be able to hide forever.”

“I may not have to.” She dropped her voice to a whisper. “Just long enough to survive until Germany is defeated and the Führer and his scum are swept away.”

Schenke shook his head. “That’s insane. The war may already be over. Poland has been conquered and Britain and France have no reason to fight. Even Britain’s colonies are starting to see the light. General Hertzog and his Boer party are pushing the South African parliament to declare a separate peace with Germany. If they succeed and other parts of the empire follow suit, Britain will not be able to fight. I believe there’s still a chance we’ll be at peace in a few months’ time.”

“You think so? You think the Führer is the kind of man who believes in peace? He doesn’t. He thrives on war. One day he will pick a fight with a more powerful nation and Germany will be crushed.”

Whatever he might think of the present regime, Schenke was a patriot, and he was offended by her words. “You saw how easily our armed forces swept through Poland. Other nations will have seen that and been warned of the consequences of waging war with us. Germany will not be defeated, and it is treason to wish it.”

Ruth regarded him thoughtfully. “I always thought that the lesson of history was that treason is measured in the damage done to a nation by certain people. It is often the case that those who most vociferously claim to be patriots turn out to cause the most harm. I think that’s true of the Führer, his party and those who blindly follow him . . . don’t you?”

Schenke did not reply, feeling his anger rise, and at the same time, a spark of fear that her words might turn out to be true. Just as had been the case in the war that had taken place earlier that century.

Ruth finished her tea. “I’d better go. I have an evening shift at Siemens.”

“I’ll see you in two days’ time.” He reached across the table impulsively and took her hand. “Be careful, Ruth.”

They exchanged a look for a beat before Schenke withdrew his hand and cleared his throat awkwardly.

“I’ll be fine.” She forced a smile, then stood and left, making sure not to hurry and draw attention to herself.

Once she had stepped out into the street, Schenke gave a deep sigh, finished his tea and indicated to the waiter that he was ready to pay. As he emerged from the café, he saw that the gray sky had become darker and an icy breeze had picked up, swirling the first small flakes of snow that had begun to fall. He pulled up his collar, shoved his hands into his pockets and strode back towards the precinct.

The Kripo section office occupied one end of the precinct building, a former barracks built during the Bismarck era, when the Prussian army had seemed invincible after crushing their Austrian and French foes. The stables at the rear had been converted into garages and storerooms, while some of the original accommodation was preserved for the use of police units whenever officers were called in from other forces to provide additional security for parades. The days when they might be required to put down communist demonstrations or to limit the transgressions of far-right paramilitaries during the troublesome years of the Republic had long since passed. The uniformed police took up most of the main building, and Schenke went to find the officer in charge of the district where the S

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...