- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

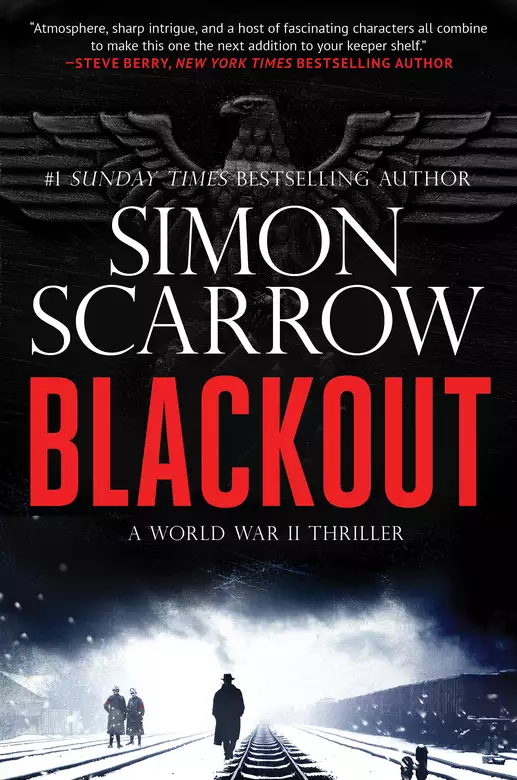

Synopsis

Berlin 1939. The city is blanketed by snow and ice. In the distance, the rumble of war grows louder. In the shadows, a serial killer rises . . .

As the Nazis tighten their chokehold on the capital, panic and paranoia fester as blackout is rigidly enforced. Every night the city is plunged into an oppressive, suffocating darkness—pitch perfect conditions for unspeakable acts.

When a young woman is found brutally murdered, it's up to Criminal Inspector Horst Schenke to solve the case quickly. His reputation is already on the line for his failure to join the Nazi Party. If he doesn't solve the case, the consequences could be fatal.

Schenke's worst fears are confirmed when a second victim is found. As the investigation takes him deeper into the regime's darkest corridors, Schenke realizes danger lurks behind every corner—and that the warring factions of the Reich can be as deadly as a killer stalking the streets . . .

Release date: March 29, 2022

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 405

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blackout

Simon Scarrow

The couple, who appeared to be in their late forties, sat slumped in their chairs in front of the stove in the larger of the two rooms of their apartment. They had been dead for days, and the skin of their faces was white, with a dull marble sheen like pearl. Both were almost naked, stripped to a grimy vest and slip. The rest of their clothing was strewn around the plain wooden chairs. There were only ashes in the stove and the cast iron was icy to the touch. The air in the room had already been below freezing when the first policeman on the scene kicked the door open. It had become colder when the window had been hurriedly opened to disperse any toxic fumes that still lingered in the small apartment.

Sergeant Kittel stood beside the stove. Despite his buttoned-up greatcoat, gloves and muffler, he was cold, and stamped his boots to keep some warmth in his feet. He was impatient as well, and every few minutes he pulled out a pocket watch and glanced at the hands. The only sound in the room was the ticking of a clock on a narrow shelf beside the stove. The noises from the street were muted by the thick snow on the ground. He could hear the exchanges of the other residents of the apartment block on the stairs and landing outside the front door. With a sigh of steamy breath, he crossed to the opening leading into the narrow hall and passed through the apartment’s door with the shattered splinters where the lock had once been. Two more policemen stood outside the entrance to the apartment, and beyond them Kittel could see a huddle of curious faces on the landing.

“Denicke! Clear those rubbernecking fools away! There is nothing to see here.” He made to turn away and stopped. “No, wait. Keep the concierge back. The rest of them should go home and keep themselves warm.”

The policeman nodded, but before he could carry out his orders, his superior spoke again. “Any sign of the criminal investigators yet?”

“No, sir.”

“Hmm.” Kittel growled irritably. He turned to the other uniformed policeman. “Get down to the entrance and keep an eye out. As soon as the Kripo officer gets here, bring him straight up. Before we all freeze to death.”

As Denicke drew his truncheon and waved the small crowd back, his colleague squeezed past the people on the landing and made his way down the four flights of stairs to the ground floor. Kittel set his expression in a hard glare as he defied the other tenants to tarry on the landing, and was gratified to see that none dared meet his eye as they turned away and made their way back to their apartments. It was good to see them respond so meekly to authority. The power of the state must be unquestioned if victory in the war was to be assured.

Not like the last time, the sergeant reflected. He had served the last two years of the Great War before returning to the political chaos that had seized Berlin. Reds rioting on the streets, demanding revolution. Well, the soldiers returning from the front had soon put an end to that nonsense. He had been part of the armed gangs that had taken on the communists and clubbed and gunned them down to restore order to the capital. There would be no stab in the back this time. Besides, the new war was already as good as over. Poland had been crushed, and it was only a matter of time before France and Britain saw the futility of another conflict when the cause of it no longer existed. Poland had disappeared, swallowed up by Germany and her Russian ally. Though if the French and the British did decide to fight on, then victory for the Fatherland was far from certain.

Kittel shrugged dismissively and rubbed his hands together. Whatever course of action the governments of Europe decided, for now a state of war existed. It was the duty of every official in Germany to ensure that discipline was maintained.

As he returned to the living room, he looked over the humble dwelling. The apartment was typical of the kind inhabited by the poorer working families in the Pankow district. There was a living space with a tiny kitchen leading off. A bathroom with a toilet and tin tub. Two bedrooms. The larger had just enough space for two single beds, which were neatly made up. On the same shelf as the clock was a photograph in a silver frame of the couple, seated with a pair of young men in uniform standing behind them. All four wore expressions of formal solemnity typical of such family portraits.

For a moment the sergeant’s heart softened as he spared a thought for the two soldiers who would soon receive a telegram informing them of their parents’ death. Such was the irony of the time that they had gone to face the perils of bullet, shell and bomb and remained unscathed, while their kin at home had died.

The only other framed pictures in the apartment were of a simple log cabin set against a backdrop of snow-clad mountains, and the ubiquitous portrait of the Führer, hand on hip and inclined forward as he stared inscrutably out of the image.

Kittel heard a car drawing up in the street. He crossed to the open window and saw the black roof and hood of one of the police pool cars reserved for officers. The front passenger door swung out and a man in a dark gray coat and black felt hat eased himself onto the cleared sidewalk. He bent to say something to the driver, then closed the door and turned to look up at the apartment block, revealing a slender face. His gaze met that of the sergeant. The policeman waiting at the entrance approached, and the new arrival lowered his head to acknowledge the salute made to him. He was waved towards the entrance of the block and both men strode across the sidewalk and disappeared from view.

It took longer for the Kripo officer to climb the stairs than Kittel had anticipated, and he noticed as the criminal investigator crossed the landing and entered the apartment that he had a slight limp. His breathing was labored too. Like the other policemen, he was wearing a thick coat, scarf, hat and gloves, but there was a businesslike directness to his demeanor as he took out the chain lanyard from around his neck and presented his metal badge. One side depicted an eagle perched on a swastika and surrounded by a wreath of oak leaves. The reverse carried the word Kriminalpolizei and the bearer’s identity number.

“Criminal Inspector Schenke, Pankow precinct,” the new arrival announced, giving a curt nod. The sergeant responded in kind as he weighed the other man up. The inspector was wide-shouldered though his body, through the thick coat, seemed lean. His slender face could have belonged to a man aged anywhere between his mid twenties and forty.

“Sergeant Kittel, Heinesdorf station.”

“You’ve picked a cold morning to call me out, Sergeant.” Schenke smiled thinly, suggesting that he was not without humor. “But then with this weather, every morning is cold.”

Winter had hit Berlin hard. The temperature had dropped below freezing a week earlier and continued to fall in the days that followed. The bitter weather had been accompanied by a severe blizzard that had covered the city in over twenty centimeters of snow. Already some of the newspapers were reporting that it was set to be one of the coldest winters for many decades. Bad at the best of times, thought Schenke, but with a war on, the hard winter added to the challenges of rationing, scarcity of coal and the blackout that consumed the city once the sun had set.

From late afternoon until the following dawn, the streets were swallowed up by the night, and Berliners were forced to grope their way to their destinations. Aside from the inconvenience, there was the danger of collision with vehicles, tripping on the curb or falling down stairs. The darkness, however, provided opportunities for some; prostitutes, for example, were less likely to draw the attention and opprobrium of the police or Hitler Youth patrols. It also allowed cover for more sinister activities. Robberies, assault and murders had increased significantly since the start of the war only four months earlier. Every night the capital became a dark and dangerous place, and those who ventured onto the streets glanced warily about them for fear of the violence that might strike at them from any alley or sheltered doorway.

“What do we have here? All I was told was that you have some bodies.”

“Yes, sir. Two. Rudolf and Maria Oberg. Through there.” Kittel stood aside to allow the inspector to enter the living room, then followed him inside. They took position either side of the stove and faced the corpses. Schenke looked from one to the other, then at the clothes on the floor and the rest of the small room.

“What information do you have so far?”

The sergeant took out his notebook and fumbled with his gloved fingers to open it before he spoke from his jottings.

“A neighbor came to the station yesterday to report that Oberg had not been at work for the last week. Both men are on the same shift at the Siemens plant. The neighbor’s wife is the concierge. I have her waiting outside. She knocked on the door yesterday but got no response, so her husband came to see us. The station chief sent me and the boys out first thing this morning to follow up. When we didn’t get any answer, we tried the door and found it locked. I gave the order to break in. We found the Obergs as you see them now.”

Schenke leaned forward to inspect the bodies more closely. “And you decided to involve the Kripo? Because?”

Kittel raised an eyebrow and gestured towards the garments strewn over the floor. “If that ain’t suspicious, then what is, sir? Who takes their clothes off in temperatures like this?”

“Quite. Was the window open when you entered the room?”

“No. It was off the latch but frozen in the frame. Needed a push to free it. My first thought was that they might have been overcome by fumes from the stove. There’s been more than a few such deaths reported since winter started.”

Schenke glanced at him. “But . . . ?”

“But their skin is mostly white, and there are signs of frostbite on the fingers and feet. If it had been fumes, there would be a red flush to their cheeks, sir.”

“Quite so.” The inspector squatted between the two chairs and examined the woman first. Her hair was dark and tied back in a bun, and she sat hunched, so that small rolls of skin formed under her jaw. Her eyes were closed and her expression was peaceful, as if she had fallen asleep. The husband, by contrast, sat drawn up, his thin arms clasped tightly around his bare knees. His face was contorted, lips drawn back in a grimace, eyes clenched shut. A fringe of gray hair ran around his crown, and there was a cut and a streak of dry blood at the back of his head.

“If it wasn’t fumes, then what do you think happened here, Kittel?”

Kittel shifted uneasily.

Schenke could see the man’s discomfort and had no wish to make it any harder for him to consider a difficult line of inquiry. It was a policeman’s duty to think through all possibilities. “Spit it out, man.”

“It could be a burglary. There are still some gypsies in Berlin, sir. And you know what they’re like. Vermin. There’s a local gang operating out of the old Siemens depot. We’re constantly dealing with the thieving bastards. There have been many burglaries, and assaults, since the blackout started, sir.”

“Very true,” Schenke said. The Kripo had been instructed to help crack down on burglaries. The orders had come from Heydrich himself. The newly appointed head of the Reich Main Security Office was keen to prove to the people that the regime would enforce law and order efficiently and ruthlessly. “And you think that perhaps the burglars came across the couple, killed them and left them like this. Why do you think the victims have been stripped?”

“I wouldn’t like to say, sir.”

“No? If our burglars were not simply here for whatever pitiful possessions they could take from this apartment, and they had more sinister motives, you would expect the woman to be undressed, right? But not the husband.”

Kittel nodded.

The inspector took off his hat and smoothed down his light brown hair. It was easier for Kittel to judge his age now—early thirties, he decided. His hair was not cropped short in the fashion of those who served in the army or the SS, but neatly cut to a conventional length. He had a broad brow that made his dark eyes seem as if they were deeper-set than they were. A narrow nose led to slightly downturned lips. He replaced his hat and gestured towards the Obergs. “It is not always the case that sex attackers just target the female, Sergeant. We must keep an open mind, eh?”

“If you say so, sir.”

Schenke folded his arms and thought for a moment. “We have two dead bodies, in a state of undress, and this wound on the head of the man.”

“Which might have been inflicted in a struggle with the gypsies, or whoever it was that did this.”

“Possibly,” Schenke conceded. “Though it’s hardly fatal, and not even incapacitating. The scalp is torn, but there’s almost no bruising. See?” He looked closely at the wound and then around the room, pointing to the floor beneath the shelf on which sat the clock and the silver-framed family portrait. “There’s a few drops of blood there.”

He stepped closer and examined the worn wooden edge at the corner of the shelf. A dark smudge drew his attention and he picked up a discarded shirt and rubbed the cloth on the wood. It came away with a dark red smear. “More blood.”

He straightened up. “Let’s see what light the concierge can throw on matters. Bring her in.”

“Sir?” Kittel hesitated. “Bring a member of the public into a crime scene?”

“We haven’t yet established that this is a crime scene. That might change depending upon what the concierge has to say.”

As Kittel left the room, the inspector went to the window and examined the latch. It was old and worn and the lug was loose in the frame so it took three attempts before he managed to secure the window. Through the smeared glass he looked up at the gray sky, streaked with trails of smoke from the chimneys of those who still had stocks of coal to burn. Beneath the haze, the roofs and streets of the capital lay under a thick layer of snow that would have filled his heart with joy were it not for the war and the two bodies in the room behind him.

“Sir. Frau Glück.”

Schenke moved away from the window and the light fell upon the bodies. The elderly woman raised a hand to her lips. “Sweet Jesus, save us!”

Schenke watched her reaction for a moment before he was satisfied her shock was natural. He stood behind the dead man as he addressed her. “I am afraid salvation is too late for some . . . You are the concierge of this building?”

She continued to stare at the corpses, eyes wide as she trembled. From cold or shock it was not possible for the inspector to decide. Most likely both, he surmised.

“Frau Glück?” He raised his voice a fraction and she tore her gaze away from the bodies and nodded.

“How well do you know the Obergs? As friends? Passing neighbors?”

She swallowed as she replied. “We stopped to talk from time to time. I keep a close eye on who comes and goes here. My husband is the block warden for this street. It’s our business to keep an eye on people.”

“Indeed.” Schenke dealt with minor party officials regularly. They were a useful source of information. They were also nosy and inclined to use their limited influence to settle scores with neighbors who got on their wrong side. His instinctive dislike of such snoopers was fueled by his ongoing difficulties with his own block warden, a municipal engineer who had become a Nazi only two years ago and was doing his best to make up for the delay in joining through fervid devotion to the ideals of the party. Despite Schenke’s distaste for the block warden system, he conceded that it had its uses as far as supplying the police with information. “I understand your husband worked with Oberg?”

“Yes . . . That is to say that Herr Oberg worked for my husband.” She stiffened her back slightly. “He is the shift overseer, you know. That’s why he noticed the absence of one of his men.”

“And yet it took some days before he did anything about it. A delay that might have saved two lives.”

She opened her mouth, ready to protest, and was met with a glare from the inspector’s dark brown eyes. She looked down. “My husband is a busy man. He has responsibilities. He can’t be expected to keep an eye on everyone.”

“But that is precisely his responsibility as block warden.” Schenke breathed in slowly and let the woman stew in her discomfort. “Let’s hope Herr Glück takes better care of his flock in future. Did the Obergs have disagreements with neighbors? Or anyone else in the street? Anyone who might have borne a grudge?”

“Not that I know of. They kept to themselves most of the time. They moved into the block fifteen years ago with their sons. Such nice boys, I thought. Always polite and respectful. They’ll be devastated.”

“I imagine they will.” Schenke clasped his hands behind his back. “That will be all for now. If there’s anything else we need to ask you, we will contact you. Thank you for your cooperation, Frau Glück.”

She looked at him with a mixture of surprise and disappointment, and was about to speak when he gave a curt nod towards the apartment’s entrance. “You may go.”

Sergeant Kittel waited until he heard her footsteps descending the stairs before he spoke. “Sir, surely there’s more we can get out of that one?”

“What exactly? If anyone who looked suspicious had entered the building she’d have come straight out with it and told us. I know her type. She’s nosy enough to know the business of everyone in the street. I am certain that she can’t help us any further. Besides, there’s been no crime here.”

Kittel’s bushy eyebrows shot up and he gestured towards the man’s body. “Sir, if it wasn’t the fumes that killed them, then what? Murder, I say. This is the work of some sick, degenerate pervert. That’s why I put the call in to Kripo. That’s why you’re here.” He continued with a faint sneer. “You’re supposed to be the smart-arses. The ones who know better than the rest of us. If you can’t see a crime when there’s evidence of one right under your nose, then what good are you to the police force, and to the Reich?”

Schenke forced himself not to react. Most of the officers and men of the Kripo still regarded themselves as professionals who were above politics. It was an attitude that did not endear them to the many in the capital’s police force who supported the party and its leader. Since they had come to power, the National Socialists had set about getting rid of those police officers who failed to embrace their ideology. But the Kripo’s expertise and experience was hard-won, and its officers had proved more difficult to replace. That said, even the legendary abilities of their former commander, Dr. Bernard Weiss, had not been enough to save him. The fact that he was a Jew outweighed all his brilliance and the long list of successes he had enjoyed against the capital’s criminals. Now Schenke found himself confronted by one of the party’s supporters. The kind of man who sneered at intellectuals and took satisfaction in seeing their ideals crushed by the new regime. It would be best not to confront Kittel’s politics. It would be better to simply pull rank.

“Sergeant, you forget yourself. I am your superior and you will respect that. I will not tolerate insubordination from any man. And I tell you now that no crime has been committed.” He turned to the bodies. “You are correct that their deaths were not caused by fumes. But you are wrong in every other respect. There is no sign of burglary. Not one hint of any search for valuables. And one of the first things a thief would have taken is the photograph frame. No, not the Führer. That silver one next to the clock. There is no evidence of any assault.”

Kittel snorted. “But the cut to the head . . .”

“. . . is the result of a fall. No doubt caused when Herr Oberg was in a delirious state before his death. Perhaps when he was tearing his clothes off.”

“Now you are talking utter nonsense, Inspector. What kind of person would take off their clothes in the middle of this freezing weather?”

“Someone who is dying from hypothermia.” Schenke looked from one body to the other with pity in his expression. “They died from the cold. There’s no fuel for the stove. It’s likely they had burned the last of their coal some days before. Look at the window latch there; it’s useless. I daresay it’s been swinging open and shut for some time. It’s probable that Oberg tried to secure the window when he was in a confused state thanks to the cold. Sometimes, not long before the end, the dying feel they are burning up and so they strip. Of course, it only hastens the end, as it did here. And if the temperature stays this low for much longer, we will be seeing more of these cases.”

He drew himself up and nodded. “It was the cold, Sergeant. Not thieves, or gypsies. Just the cold. This is not a job for the Kripo. You’ll have to write the report. And next time, I hope you’ll think twice before you call us out.”

He inclined his head in farewell and the policeman stepped back to let him pass, shaping to raise his arm. “Hail . . .”

But Schenke had already strode off, quickening his pace to avoid any exchange of the salute the party had introduced. It had always struck him as cheaply theatrical, like so many of the trappings of national socialism that strove to achieve drama and spectacle to excite their followers.

As he made his way down the stairs, he frowned. By the time he returned to his office at the precinct, over two hours would have been wasted. Time he could have spent dealing with the ongoing investigation into a ring of ration coupon forgers. All because the sergeant wanted a fresh excuse to target those gypsies who remained in the district.

At the bottom of the stairs, he passed the open door of the concierge’s apartment. Frau Glück stood on the threshold. He touched the brim of his hat and stepped out into the bright street.

Even though the sky was overcast, the glare of the snow caused him to wrinkle his eyes. The driver had left the engine running, against fuel-saving regulations, in order to keep the car’s heater going. Schenke slipped into the passenger seat without comment, grateful for the heat inside the vehicle. As the driver put the Opel into gear, the inspector took one last look at the gray facade of the apartment block. The concierge had emerged from her doorway to stand at the entrance, and their eyes met. He could not be sure, but he thought there was a touch of guilt in her expression. As well there should be. A terrible winter had come to Berlin. It was the duty of all the capital’s inhabitants to look out for each other in the freezing days to come. If nothing else had been achieved in this pointless diversion, Schenke hoped that Frau Glück and her husband would take better care of their neighbors.

“Back to the precinct, sir?”

“Yes. And take it slowly. There’s ice on the streets.”

There was no sense in adding fresh names to the list of victims claimed by this harshest of winters, thought Schenke. No sense at all.

The Kripo section at the Pankow precinct had a modest staff of less than ten men under Schenke’s command, four of whom were still in training or serving out their probation period before they qualified. There were also two women, whose duties included dealing with children and vulnerable females involved in investigations. In normal circumstances there would have been another six investigators, but the exigencies of war had demanded the transfer of men away from peacetime duties. The section’s offices were on the top floor of the precinct building, overlooking the yard containing garages, workshops, storerooms and a small barrack block. It was up three flights of stairs, and Schenke grimaced as he made the climb, favoring his bad leg. Although it was over six years since the motor-racing accident that had nearly killed him, his left knee was still stiff and painful, especially during the cold, damp winter months. He could walk without difficulty, but climbing stairs or any attempt to run more than a hundred meters caused a shooting pain in the joint. It was enough to render him unfit for military service.

That was a cause of shame to him, since many of his colleagues had been drafted into the forces to serve Germany in the recent war with Poland. With luck, peace would soon return to the continent, the men would resume their old occupations and Schenke would no longer have to be conscious of his failure to contribute to the Reich’s war effort.

He paused at the top of the stairs, glanced down the corridor to make sure he was alone and bent over to massage the muscles around the knee, easing the stiffness and pain. Straightening, he made himself stride to the entrance of the Kripo’s offices, and entered a room ten meters in length by four. Desks were arranged on either side, paired face-to-face. On the wall opposite the door was a line of windows, the glass covered in condensation and patches of ice on the inside. Notice boards hung along the side wall. Less than half his staff were at their desks, and they looked up as he entered. The rest were out on duty. In other branches of the police force they would have stood up for a superior officer, but the men and women belonging to the Kripo were plainclothes professionals and were content to eschew such formalities and get on with the job.

His second-in-command, Sergeant Hauser, a veteran policeman of nearly thirty years, turned his chair to face Schenke. He was sturdily built from his days boxing in the army, and his cropped hair looked like a sprinkling of pepper across the crown of his head.

“Got a new case for us, sir?”

Schenke shook his head. “Thankfully not, Hauser. Nothing suspicious. Almost a complete waste of time, in fact.”

“Almost?”

“It gave me the chance to teach one of the uniformed boys not to waste our time.”

Hauser smiled. There was always an edge to relations between criminal investigators and the beat police known as the Orpo.

Schenke took off his coat and folded it over his arm but kept his hat and scarf in place. “Any news from the technical lab about the ration coupons we found at the Oskar warehouse?”

“Sure.” Hauser turned to his desk and reached for a buff folder. “This came in while you were out. I’ve only had time to look at the summary. But it makes for interesting reading.”

“Bring it through to my office. I’ll have a look over some coffee.” Schenke caught the eye of the most junior member of the section, a chubby youth with slicked-back blond hair. “Brandt!”

The young man stood up. “Sir?”

“Coffee for me and Hauser. Right away.”

Brandt nodded and hurried out of the office towards the staff room at the end of the corridor.

“You always pick on the kid. Why not ask one of the girls?” Hauser muttered.

“He’s fresh out of Charlottenberg and needs to pay his dues. Like you and I both did.”

Schenke glanced towards the two desks where his female officers sat. Frieda Echs was in her mid forties and solidly built. She wore her brown hair in a short, almost manly cut. Opposite her sat Rosa Mayer, ten years younger, with blonde hair and the kind of finely structured face that made her look like a film star. Plenty of men in the precinct had tried to win her affection, but she had rebuffed any advances by saying she had a suitor who worked in Reichsführer Himmler’s private office. Whether she was telling the truth or not, it served to ensure she was never troubled more than once by the same man.

“Besides,” he continued, “Frieda and Rosa have earned their place in our little world here at Pankow. Until Brandt completes his probation, he makes the coffee.”

Hauser shrugged his heavy shoulders and ran a large hand over his head. “That’s not how it was back in the day.”

“Then chalk up a win for progress, my friend. Let’s have a look at this report.”

Schenke led the way through the room to the glassed-in cubicle at the far end, nodding a greeting to the officers he passed along the way. A neat brass plate with his rank and name inscribed in a gothic style was screwed to the door. He opened it. There was a bookcase and a filing cabinet against the wall opposite the window; in between was his desk, a battered and worn-looking relic from the previous century. He had been offered a replacement when he took up the post, but had declined, preferring to keep the old one. It was large, solid and redolent of tradition and good service; somehow reassuring and imposing. Because of its size, there was barely enough room for the two chairs for visitors set to the right of the door.

Behind the desk, a portrait of the Führer in a gleaming black frame stared down the length of the section’s office. Unlike the desk, it had not been a feature of the office during the time of Schenke’s predecessor. It had been hung there shortly after Schenke’s arrival, on the orders of the precinct commander, a corpulent man who had been appointed out of loyalty to the party rather than any proven competence. Schenke had left the picture in place and tried to ignore it, taking some pleasure at having his back turned to the Führer.

Pausing to hang his coat on a hook and slip off his leather gloves,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...