- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

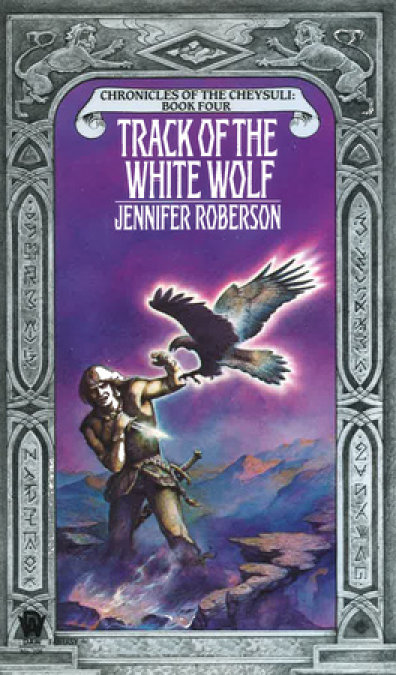

The fourth book in the Chronicles of the Cheysuli continues a tale of magical warriors and shapeshifters as they battle the sorcerers that threaten their existence

Niall, Prince of Homana, key player in a prophecy that spans generations, should have been the treasured link between Cheysuli and Homanan. Yet neither of the peoples he is destined to someday rule feel anything but suspicion of Niall. Homanans fear him for his Cheysuli heritage, while Cheysuli refuse to accept him as their own because he has acquired neither a lir-shape nor the lir companion that is the true mark of the Cheysuli shapechangers.

And now, despite his precarious situation within the kingdom, Niall must undertake a journey to fulfill yet another link in the ancient prophecy. He must travel through war-torn lands to claim his bride—a mission which may prove his doom. For searching for both his destiny and his lir, Niall is about to be plunged into a dangerous maelstrom of intrigue, betrayal, and deadly Ihlini sorcery....

Release date: April 7, 1987

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Track of the White Wolf

Jennifer Roberson

DAW titles by Jennifer Roberson

THE SWORD-DANCER SAGA

SWORD-DANCER

SWORD-SINGER

SWORD-MAKER

SWORD-BREAKER

SWORD-BORN

SWORD-SWORN

SWORD-BOUND

CHRONICLES OF THE CHEYSULI

SHAPECHANGERS

THE SONG OF HOMANA

LEGACY OF THE SWORD

TRACK OF THE WHITE WOLF

A PRIDE OF PRINCES

DAUGHTER OF THE LION

FLIGHT OF THE RAVEN

A TAPESTRY OF LIONS

THE GOLDEN KEY

(with Melanie Rawn and Kate Elliott)

ANTHOLOGIES

(as editor)

RETURN TO AVALON

HIGHWAYMEN: ROBBERS AND ROGUES

CHRONICLES

OF THE CHEYSULI:

BOOK FOUR

TRACK OF THE

WHITE WOLF

JENNIFER ROBERSON

DAW BOOKS, INC.

DONALD A. WOLLHEIM, FOUNDER

375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

ELIZABETH R. WOLLHEIM

SHEILA E. GILBERT

PUBLISHERS

www.dawbooks.com

For the readers.

THE HOUSE OF HOMANA

Table of Contents

Prologue

I knelt in silence, in patience, right knee cushioned by layers of rain-soaked leaves. Boot heel pressed against buttock; the foot within the boot, perversely, threatened suddenly to cramp.

Not now, I told it, as if the thing might listen.

My left leg jutted up, offering a thigh on which I could rest the arm supporting the compact bow, support I needed badly. I had knelt a very long time in the misted forest, keeping my silence and my patience only because the discipline my father and brother had taught me, for once, held true. Perhaps I was finally learning.

How many times did Carillon kneel as I kneel, lying in wait for the enemy?

My grandsire’s name slipped easily into mouth or mind. Perhaps for another man, perhaps for another grandson, it would not. But for me, it was a legacy I did not always desire.

—Carillon would keep still for hours—Carillon would never speak—Carillon would know best how to do the job—

Distracted by my thoughts, I did not hear the sound behind me. I sensed only the shadow, the weight of the stalking beast—

Even as I tried to turn on cramping foot, the bow was knocked flying from my hands. Half-sheathed claws shredded leather hunting doublet and, beneath that, linen shirt. Weight descended and crushed me to the ground, grinding my face into damp leaves and soggy turf.

In the cold, breath rushed out of my nose and mouth like smoke from a dragon’s gullet. Mountain cat.

I knew it at once, even as the cat’s weight shifted and allowed me room to move. There is a smell, not unpleasant, about the cats. A sense of presence. An ambience, created the moment one of their kind appears.

I rolled, coming up onto my knees, jerking the knife free of the sheath at my belt—

—and froze.

A female. Full-fleshed and in prime condition. Her lush red coat was a dappled chestnut at shoulders and haunches. The tail lashed in short, vicious arcs as she crouched. Dark-tipped ears flattened against wedge-shaped head as she snarled, displaying an awesome assemblage of curving teeth.

She hissed, as a housecat will do when taken by surprise.

And then she purred.

I swore. Slammed the knife home into its sheath. Spat out mud and stripped decaying leaf from face and hair. And swore again as I saw the laughter in her amber, slanted eyes.

And suddenly I knew—

I glanced back instantly. In the clearing, very near the place I had waited so patiently, the red stag lay dead, the king stag, with the finest rack of antlers I had ever seen. And a red-fletched arrow stood up like a standard from his ribs.

“Ian!” I shouted. “Ian—come out! It was not fair!”

The cat sat down in the clearing, commenced licking one big paw, and continued to purr noisily.

“Ian?” I looked suspiciously at the cat a moment. “No—Tasha.” Still there was no answer. It was all I could do not to fill the trees with my shout. “Ian, the stag was mine—do you hear?” I waited. Wiggled my foot inside my boot; the cramp, thank the gods, was fading. “Ian,” I said menacingly; giving up, I bellowed it. “The stag was mine not yours!”

“But you were much too slow.” The answering voice was human, not feline. “Much too slow; did you think the king would wait on a prince forever?”

I spun around. As usual, with him, I had misjudged his position. There were times I would have sworn he could make his voice issue from rock or tree, and me left searching fruitlessly for a man.

My brother sifted out of trees, brush, slanted foggy shadows into the clearing beside the dead stag. Now that I saw him clearly, I wondered that I had not seen him before. He had been directly across from me. Watching. Waiting. And laughing, no doubt, at his foolish younger brother.

But in silence, so he would not give himself away.

I swore. Aloud, unfortunately, which only gave him more cause to laugh. But he did not, aloud; he merely grinned his white-toothed grin and waited in amused tolerance for me to finish my royal tirade.

And so I did not, having no wish to hand him further reason to laugh at me, or—worse—to dispense yet another of his ready homilies concerning a prince’s proper behavior.

I glared at him a moment, unable to keep myself from that much. I saw the bow in his hands and the red-fletched arrows poking up from the quiver behind his shoulder. And looked again at the matching arrow in the ribs of the red king stag.

Conversationally, I pointed out, “Using your lir to knock me half-silly was not within the rules of the competition.”

“There were no rules,” he countered immediately. “And what Tasha did was her own doing, no suggestion of mine—though, admittedly, she was looking after my interests.” I saw the maddening grin again; winged black brows rose up to disappear into equally raven hair. “And her own, naturally, as she shares in the kill.”

“Of course,” I agreed wryly. “You would never set her on me purposely—”

“Not for a liege man to do,” he agreed blandly, with an equally bland smile. Infuriating, is my older brother.

“You ought to teach her some manners.” I looked at the mountain cat, not at my brother. “But then, she has arrogance enough to match yours just as she is, so I am sure you prefer her this way.”

Ian, laughing—aloud this time—did not answer. Instead he knelt down by the stag to inspect his kill. In fawn-colored leathers he blended easily into the foliage and fallen leaves. Another man, lacking the skills I have learned, would not have seen Ian at all, until he moved. Even then, I thought only the glint of gold on his bare arms would give him away.

I should have known. I should have expected it. All a man has to do is look at him to know he is the better hunter. Because a man, looking at my brother, will see a Cheysuli warrior.

But a man, looking at me, will see only a fellow Homanan. Or Carillon, until he looks again.

For all we share a Cheysuli father, Ian and I share not a whit of anything more. Certainly not in appearance. Ian is all Cheysuli: black-haired, dark-skinned, yellow-eyed. And I am all Homanan: tawny-haired, fair-skinned, blue-eyed.

It may be that in a certain gesture, a specific movement, Ian and I resemble one another. Perhaps in a turn of phrase. But even that seems unlikely. Ian was Keep-raised, brought up by the clan. I was born in the royal palace of Homana-Mujhar, reared by the aristocracy. Even our accents differ a little: he speaks Homanan with the underlying lilt of the Cheysuli Old Tongue, frequently slipping into the language altogether when forgetful of his surroundings; my speech is always Homanan, laced with the nuances of Mujhara, and almost never do I fall into the Old Tongue of my ancestors.

Not that I have no wish to. I am Cheysuli as much as Ian—well, nearly; he is half, I claim a quarter—and yet no man would name me so. No man would ever look into my face and name me, in anger or awe, a shapechanger, because I lack the yellow eyes. I lack the color entirely; the gold, and even the language.

No. No shapechanger, the Cheysuli Prince of Homana.

Because in addition to lacking Cheysuli looks, I also lack a lir.

PART I

One

I think no one can fully understand what pain and futility and emptiness are. Not as I understand them: a man without a lir. And what of them I do understand comes not of the body but of the spirit. Of the soul. Because to know oneself a lirless Cheysuli is an exquisite sort of torture I would wish on no man, not even to save myself.

My father was young, too young, when he received his lir, and then he bonded with two: Taj and Lorn, falcon and wolf. Ian was fifteen when he formed his bond with Tasha. At ten, I hoped I would be as my father and receive my lir early. At thirteen and fourteen I hoped I would at least be younger than Ian, if I could not mimic my father. At fifteen and sixteen I prayed to all the gods I could to send me my lir as soon as possible, period, so I could know myself a man and a warrior of the clan. At seventeen, I began to dread it would never happen, never at all; that I would live out my life a lirless Cheysuli, only half a man, denied all the magic of my race.

And now, at eighteen, I knew those fears for truth.

Ian still knelt by the king stag. Tasha—lean, lovely, lissome Tasha—flowed across the clearing to her lir and rubbed her head against one bare arm. Automatically Ian slipped that arm around her, caressing sleek feline head and tugging affectionately at tufted ears. Tasha purred more loudly than ever, and I saw the distracted smile on Ian’s face as he responded to the mountain cat’s affection. A warrior in communion with his lir is much like a man in perfect union with a woman; another man, shut out of either relationship, is doubly cursed…and doubly lonely.

I turned away abruptly, knowing again the familiar uprush of pain, and bent to recover my bow. The arrow was broken; Tasha’s mock attack had caused me to fall on it. A sore hip told me I had also rolled across the bow. But at least the soreness allowed me to think of things other than my brother and his lir.

I have never been a sullen man, or even one much given to melancholy. Growing up a prince and heir to the throne of Homana was more than enough for most; would have been more than enough for me, were I not Cheysuli-born. But lirlessness—and the knowledge I would remain so—had altered my life. Nothing would change it, not now; no warrior in all the clans had ever reached his eighteenth birthday without receiving his lir. Nor, for that matter, his seventeenth. And so I tried to content myself with my rank and title—no small things, to the Homanan way of thinking—and the knowledge that for all I lacked a lir, I was still Cheysuli. No one could deny the Old Blood ran in my veins. No one. Not even the shar tahl, who spoke of rituals and traditions very carefully indeed when he spoke of them to me, because—for all I lacked a lir—I still claimed the proper line of descent. And that line would put me on the Lion Throne of Homana the day my father died.

That, at least, was something my brother could not lay claim to—not that he would wish to. Being bastard-born of my father’s Cheysuli meijha—light woman, in Homanan—attached no stigma to him in the clans. Cheysuli do not place such importance on legitimacy; in the clans, the birth of another Cheysuli is all that counts, but as far as the Homanans were concerned, Donal’s eldest son was tolerated among the Homanan aristocracy only because he was the son of the Mujhar.

And so Ian, as much as myself, knew what it was to lack absolute acceptance. It was, I suppose, his own part of the discordant harmony in an otherwise pleasing melody. It only manifested itself for a different reason.

“Niall—?” Ian rose with the habitual grace I tried to emulate and could not; I am too tall, too heavy. I lack the total ease of movement born in so many Cheysuli. “What is it?”

I thought I had learned to mask my face, even to Ian. It served no purpose to tell him what torture it was to see my brother with his lir, or my father with his. Most of the time it remained a dull ache, and bearable, as a sore tooth is bearable so long as it does not turn rotten in the jaw. But occasionally the tooth throbs, sending pain of unbearable intensity through my mind; my mask had slipped, and Ian had seen the face I wore behind it.

“Rujho—” so quickly he slipped into the Old Tongue—“are you ill?”

“No.” Abrupt answer, too abrupt; I inspected the bow again, for want of another action to cover my brief slip. “No, only—” I sought a lie to cover up the pain “—only disappointed. But I should know better than to match myself against you in something so—” I paused—“so Cheysuli as hunting a stag. You have only to take lir-shape, and the contest is finished.”

Ian indicated the arrow. “No lir-shape, rujho. Only human form.” He smiled, as if he knew we joked, but something told me he knew well enough what had prompted my discomfiture. “If it pleases you, Niall, I will concede. Without Tasha’s interference, you might well have taken the stag.”

I laughed at him outright. “Oh, aye, might have. Such a concession, rujho! You will almost have me believing I know what I am doing.”

“You know what I taught you, my lord.” Ian grinned. “And now, if you like, I will go fetch the horses as a proper liege man so we may escort the dead king home in honor.”

“To Homana-Mujhar?” The palace was at least two hours away; rain threatened again.

“No, I thought Clankeep. We can prepare the stag there for a proper presentation. Old Newlyn knows all the tricks.” Ian bent down and with a quick twist removed the unbroken arrow from between the ribs of the stag. “Clankeep is closer, for all that.”

I shut my mouth on an answer and did not say what I longed to: that I much preferred the palace. Clankeep is Cheysuli; lirless, I am extremely uncomfortable there. I avoid it when I can.

Ian glanced up. “Niall, it is your home as much as Mujhara.” So easily he read me, even by my silence.

I shook my head. “Homana-Mujhar is my place. Clankeep is yours.” Before he could speak I turned away. “I will get the horses. My legs are younger than yours.”

It is an old joke between us, the five years that separate us, but for once he would not let it go. He stepped across the dead king stag and caught my arm.

“Niall,” The levity was banished from his face. “Rujho, I cannot pretend to know what it is to lack a lir. But neither can I pretend your lack does not affect me.”

“Does it?” Resentment flared up instantly, surprising even me with its intensity. But this was intrusion into an area of my life he could not possibly understand. “Does it affect you, Ian? Does it disturb you that the warriors of the clan refer to me as a Homanan instead of a Cheysuli? Does it affect you that if they could, they would petition the shar tahl to have my birth-rune scratched off the permanent birth-lines?” His dark face went gray as death, and I realized he had not known I was aware of what a few of the more outspoken warriors said. “Oh, rujho, I know I am not alone in this. I know it must disturb you—a full-fledged Cheysuli warrior and a member of Clan Council—in particular: that the man intended to rule after Donal lacks the gifts of the Cheysuli. How could it not? You serve the prophecy as well as any warrior, and yet you look at me and see a man who does not fit. The link that was not forged.” It hurt me to see the pain in his yellow eyes; eyes some men still called bestial. “It affects you, it affects our sister, it affects our father. It even affects my mother.”

Ian’s hand fell away from my arm. “Aislinn? How?”

His tone was unguarded; I heard the note of astonishment in his voice. No, he would not expect my lack of a lir to affect my mother. How could it, when the Queen of Homana was fully Homanan herself, without a drop of Cheysuli blood?

How could he, when there was so little of affection between them? Not hatred; never that. Not even a true disliking of one another. Merely—toleration. A mutual apathy.

Because my mother, the Queen, recalled too clearly that what love my father had to offer had been given freely to his Cheysuli meijha, Ian’s mother, and not to the Homanan princess he had wed.

At least, not then.

I smiled, albeit wryly, more than a little resigned. “How does it affect my mother? Because to her, my lacking a lir emphasizes a certain other bloodline in me. It reminds her that in addition to looking almost exactly like her father, I reflect all his Homanan traits. No Cheysuli in me, oh no; I am Homanan to the bone. I am Carillon come again.”

The last was said a trifle bitterly; for all I am used to the fact I look so much like my grandsire, it is not an easy knowledge. I would sooner do without it.

Ian sighed. “Aye. I should have seen it. The gods know she goes on and on about Carillon enough, linking her son with her father. There are times I think she confuses the two of you.”

I shied away from that idea almost at once. It whispered of sickness; it promised obsession. No son wishes to know his mother obsessed, even if she is.

And she was not. She was not.

“Clankeep,” I said abruptly. “Well enough, then let us go. We owe this monarch more than a bed of leaves and bloodied turf.”

A muscle ticked in Ian’s jaw. “Aye,” he said tersely; no more.

I went off to fetch the horses.

Once, individual keeps had been scattered throughout Homana, springing up like toadstools across the land. Once, they had even reached a finger here and there into neighboring Ellas, when Shaine’s qu’mahlin had been in effect. The purge had resulted in the destruction of Cheysuli holdings as well as much of the race itself. Later the Solindish king, Bellam, had usurped the Lion Throne and laid waste to Homana in the name of Tynstar, Ihlini sorcerer, and devotee of the god of the netherworld. With Carillon in exile and the Cheysuli hunted by Solindish, Ihlini and Homanan alike, what remained of the Cheysuli was nearly destroyed completely. The keeps had been sundered into heaps of shattered stone and shreds of painted cloth.

My legendary grandsire had, thank the gods, come home again to take back his stolen throne; his return ended Solindish and Ihlini domination and Shaine’s purge. Freed of the threat of extirpation, the Cheysuli had also come home from secret keeps and built Homanan ones again. Clankeep itself, spreading across the border between woodlands and meadowlands, had gone up after Donal succeeded to the Lion on Carillon’s death. And though the Cheysuli were granted freedom to live where they chose after decades of outlawry, they still preferred the closeness of the forests. Clankeep, ringed by un-mortared walls of undressed, gray-green stone, was the closest thing to a city the Cheysuli claimed.

As always, I felt the familiar admixture of emotions as we entered the sprawling keep: sorrow—a trace of trepidation—a fleeting sense of anger—an undertone of pride. A skein of raw emotions knotted itself inside my soul…but mostly, more than anything, I knew a tremendous yearning to belong as Ian belonged.

Clankeep is the heart of the Cheysuli, regardless that my father rules from Homana-Mujhar. It is Clankeep that feeds the spirit of each Cheysuli; Clankeep where the shar tahls keep the histories, traditions and rituals clear of taint. It is here they guard the remains of the prophecy of the Firstborn, warding the fragmented hide with all the power they can summon.

And it was here at Clankeep that Niall of Homana longed to spend his days, for all he was prince of the land.

Because then he would be Cheysuli.

The rain began again, though falling with less force than before. This was more of a mist, kiting on the wind. Sheets of it, shredded by the gusts, drifted before my horse. It muffled the sounds of the Keep and drove the Cheysuli inside their painted pavilions.

Except for Isolde. I should have known; ’Solde adores the rain, preferring thunder and lightning in abundance. But this misting shower, I knew, would do; it was better than boring sunlight.

“Ian! Niall! Both my rujholli at once?” She wore crimson, which was like her; it stood out against the damp grayness of the day as much as her bright ebullience did. I saw her come dashing through the drifting wet curtains as if she hardly felt them, damp wool skirts gathered up to show off furred boots of sleek dark otter pelt. Silver bells rimmed the cuffs of the boots, chiming as she ran. Matching bells were braided into thick black hair; like Ian, she was all Cheysuli. Even to the Old Blood in her veins.

“What is this?” She stopped as we did, putting out a hand to push a questing wet muzzle from her face; Ian’s gray stallion was a curious sort, and oddly affectionate toward our sister. But then, perhaps it was the magic in her showing. “The king stag!” Yellow eyes widened as she looked up at Ian and me. “How did you come by this?”

’Solde seemed untroubled by the rain, falling harder now, that pasted hair against scalp and dulled the shine of all her bells. One hand still on the stallion’s muzzle, she waited expectantly for an explanation.

I blew a drop of water off the end of my nose. “’Solde, you have eyes. The king stag, aye, and brought down by Ian’s hand—” I paused “—in a manner of speaking.”

Ian glared. “What nonsense is this? ‘In a manner of speaking.’ I took him down with a single arrow! You were there.”

“How kind of you to recall it.” I smiled down at ’Solde. “He set Tasha on me the moment I prepared to loose my own arrow, and the cat spoiled my shot.”

’Solde laughed, smothered it with a hand, then attempted, unsuccessfully, to give Ian a stern glance of remonstration. At three years younger than Ian and two years older than I, she did what she could to mother us both. Though I had my own mother in Homana-Mujhar, ’Solde and Ian did not; Sorcha was long dead.

Rain fell harder yet. My chestnut gelding snorted and shook himself, jostling all my bones. I was already a trifle stiff from Tasha’s mock attack; I needed no further reminding of human fragility. “’Solde, do you mind if we go into Ian’s pavilion? You may like the rain, but we have been out in it longer than I prefer.”

Her slim brown fingers caressed the crown bedecking the king stag’s head. “So fine, so fine…a gift for our jehan?” She asked it of Ian, whose stallion bore the stag before the Cheysuli saddle.

“He will be pleased, I think,” Ian agreed “’Solde, Niall has the right of it. I will shrink like an old wool tunic if I stay out in this downpour a moment longer.”

’Solde stepped aside, shaking her head in disappointment, and all the bright bells rang. “Babies, both of you, to be so particular about the weather. Warriors must be prepared for anything. Warriors never complain about the weather. Warriors—”

“’Solde, be still,” Ian suggested, calmly reining his stallion toward the nearest pavilion. “What you know of warriors could be fit into an acorn.”

“No,” she said, “at least a walnut. Or so Ceinn tells me.”

The stallion was stopped short, so short my own mount nearly walked into the dappled rump, which is not something I particularly care to see happen around Ian’s prickly stallion. But for once the gray did nothing.

Ian, however, did. “Ceinn?” He twisted in the saddle and looked back at our smug-faced sister. “What has Ceinn to say about how much you know of warriors?”

“Quite a lot,” she answered off-handedly. “He has asked me to be his cheysula.”

“Ceinn?” Ian, knowing the warriors better than I, could afford to sound astonished; all I could do was stare. “Are you sure he said cheysula and not meijha?”

“The words do have entirely different sounds,” ’Solde told him pointedly, which would not please Ian any at all. But then, of course, she did not mean to. “And I do know the difference.”

Ian scowled. “Isolde, he has said nothing to me about it.”

“You have been in Mujhara,” she reminded him. “For weeks. Months. And besides, he is not required to say anything to you. It is me for whom he wishes to offer.”

Ian, still scowling, cast a glance at me. “Well? Are you going to say nothing to her?”

“Perhaps I might wish her luck,” I answered gravely. “Whenever has anything we have said to her made the slightest amount of difference?”

“Oh, it has,” Isolde said. “You just never noticed.”

Ian shut his eyes. “Her mind, small as it is, astonishes me with its capacity for stubbornness, once a decision is made.” Eyes open again, he twisted his mouth in a wry grimace of resignation. “Niall has the right of it: nothing we say will make any difference. But—why Ceinn?”

“Ceinn pleases me,” she answered simply. “Should there be another reason?”

Ian glanced at me, and I knew our thoughts ran along similar paths: for a woman like our sister, a free Cheysuli woman with only bastard ties to royalty, there need be no other reason.

For the Prince of Homana, however, there were multitudinous other reasons. Which was why I had been cradle-betrothed to a cousin I had never seen.

Gisella was her name. Gisella of Atvia. Daughter of Alaric himself, and my father’s sister, Bronwyn.

I smiled down at my Cheysuli half-sister. “No, ’Solde. No other reason. If he pleases you, that is enough for Ian and me.”

“Aye,” Ian agreed glumly. “And now that you have taken us by surprise, ’Solde, as you intended all along, may we get out of the rain?”

’Solde grinned the grin that Ian usually wore. “There is a fire in your pavilion, rujho, and hot honey brew, fresh bread, cheese and a bit of venison.”

Ian sighed. “You knew we were coming.”

’Solde laughed. “Of course I did. Tasha told me.”

And with those well-intentioned words, my sister once more reminded me even she claimed gifts that I could not.

Two

The rain began to fall a trifle harder. Isolde flapped a hand at us both. “Go in, go in, before the food and drink grow cold. I have my own fire to tend, and then I will come back.”

She was gone, crimson skirts dyed dark by the weight of the rain. I heard the chime of bells as ’Solde ran toward her pavilion (did she share it now with Ceinn?) and reflected the sound suited my sister. There was nothing of dark silence about Isolde.

“Go on,” Ian told me. “Old Newlyn will wish to see the stag now in order how best to judge the preparation. There is no need for you to get any wetter. Tasha will keep you company.”

Ian did not bother to wait for my answer; much as I dislike to admit it, he is accustomed to having me do as he tells me to. Prince of Homana—liege man; one would think Ian did my bidding, but he does it only rarely. Only when it suits that which he believes appropriate to a liege man’s conduct.

I watched him go much as ’Solde had gone, fading into the wind and rain like a creature born of both. And she had the right of it, my rujholla; warriors did not complain about the weather. Warriors were prepared for anything.

Or perhaps it was just that they knew how to make themselves look prepared, thereby fooling us all.

I grinned and

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...