- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

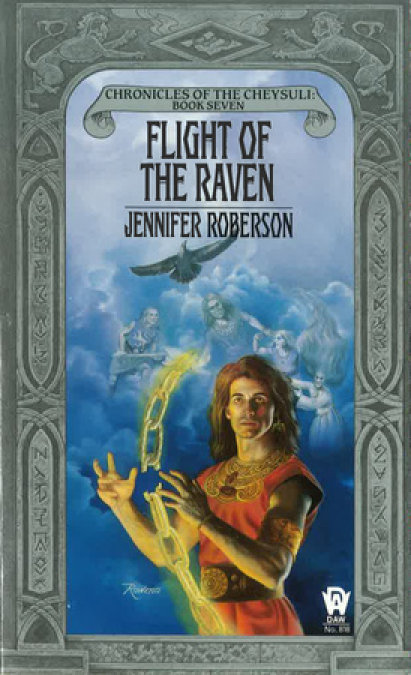

The seventh book in the Chronicles of the Cheysuli continues a tale of magical warriors and shapeshifters as they battle the sorcerers that threaten their existence

Aidan, only child of Brennan and Aileen, and the grandson of Niall, is heir to the Lion Throne of Homana and inheritor, too, of a prophecy carried down through the generations and finally on the verge of fulfillment. But will Aidan, driven as he is by strange visions and portents, prove the weak link in the ages-old prophecy—the Cheysuli who fails to achieve his foretold destiny? For as Aidan prepares to set out for Erinn to claim his betrothed, he will become the focus of forces out of legend, visited by the ghosts of long-dead kinsmen, and by the Hunter, a mysterious being who may be a Cheysuli god incarnate.

Commanded by the Hunter to undertake a quest to claim a series of "god-given" golden links, Aidan will find himself challenged by the Cheysuli's most deadly foe—Lochiel, the son of Strahan—who will use every trick of Ihlini sorcery to stop Aidan and destroy the promise of the prophecy once and for all....

Release date: June 5, 1990

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Flight of the Raven

Jennifer Roberson

CHRONICLES

OF THE CHEYSULI:

BOOK SEVEN

FLIGHT OF

THE RAVEN

JENNIFER ROBERSON

Don’t miss JENNIFER ROBERSON’S monumental fantasies:

CHRONICLES OF THE CHEYSULI:

SHAPECHANGERS

THE SONG OF HOMANA

LEGACY OF THE SWORD

TRACK OF THE WHITE WOLF

A PRIDE OF PRINCES

DAUGHTER OF THE LION

FLIGHT OF THE RAVEN

A TAPESTRY OF LIONS

THE NOVELS OF TIGER AND DEL:

SWORD-DANCER

SWORD-SINGER

SWORD-MAKER

SWORD-BREAKER

SWORD-SWORN

SWORD-BORN

SWORD-BOUND

KARAVANS:

KARAVANS

DEEPWOOD

THE WILD ROAD

This one is for S.J. Hardy, who, loving to read, married a woman exactly the same.

Eventually they begat four children who, in their turn, had the great good sense to pass along the reading gene to yet a third generation.

When my turn comes, I’ll try my best to do the same.

Thanks, Granddaddy!

Table of Contents

The Chronicles of the Cheysuli: An Overview

THE PROPHECY OF THE FIRSTBORN:

“One day a man of all blood shall unite, in peace, four warring realms and two magical races.”

Originally a race of shapechangers known as the Cheysuli, descendants of the Firstborn, Homana’s original race, held the Lion Throne, but increasing unrest on the part of the Homanans, who lacked magical powers and therefore feared the Cheysuli, threatened to tear the realm apart. The Cheysuli royal dynasty voluntarily gave up the Lion Throne so that Homanans could rule Homana, thereby avoiding fullblown internecine war.

The clans withdrew altogether from Homanan society save for one remaining and binding tradition: each Homanan king, called a Mujhar, must have a Cheysuli liege man as bodyguard, councillor, companion, dedicated to serving the throne and protecting the Mujhar, until such a time as the prophecy is fulfilled and the Firstborn rule again.

This tradition was adhered to without incident for nearly four centuries, until Lindir, the only daughter of Shaine the Mujhar, jilted her prospective bridegroom to elope with Hale, her father’s Cheysuli liege man. Because the jilted bridegroom was the heir of a neighboring king, Bellam of Solinde, and because the marriage was meant to seal an alliance after years of bloody war, the elopement resulted in tragic consequences. Shaine concocted a web of lies to salve his obsessive pride, and in so doing laid the groundwork for the annihilation of a race.

Declared sorcerers and demons dedicated to the downfall of the Homanan throne, the Cheysuli were summarily outlawed and sentenced to immediate execution if found within Homanan borders.

Shapechangers begins the “Chronicles of the Cheysuli,” telling the tale of Alix, daughter of Lindir, once Princess of Homana, and Hale, once Cheysuli liege man to Shaine. Alix is an unknown catalyst bearing the Old Blood of the Firstborn, which gives her the ability to link with all lir and assume any animal shape at will. But Alix is raised by a Homanan and has no knowledge of her abilities, until she is kidnapped by Finn, a Cheysuli warrior who is Hale’s son by his Cheysuli wife, and therefore Alix’s half-brother. Kidnapped with her is Carillon, Prince of Homana. Alix learns the true power in her gifts, the nature of the prophecy which rules all Cheysuli, and eventually marries a warrior, Duncan, to whom she bears a son, Donal, and, much later, a daughter, Bronwyn. But Homana’s internal strife weakens her defenses. Bellam of Solinde, with his sorcerous aide, Tynstar the Ihlini, conquers Homana and assumes the Lion Throne.

In The Song of Homana, Carillon returns from a five-year exile, faced with the difficult task of gathering an army capable of overcoming Bellam. He is accompanied by Finn, who has assumed the traditional role of liege man. Aided by Cheysuli magic and his own brand of personal power, Carillon is able to win back his realm and restore the Cheysuli to their homeland by ending the purge begun by his uncle, Shaine, Alix’s grandfather. He marries Bellam’s daughter to seal peace between the lands, but Electra has already cast her lot with Tynstar the Ihlini, and works against her Homanan husband. Carillon’s failure to father a son forces him to betroth his only daughter, Aislinn, to Donal, Alix’s son, whom he names Prince of Homana. This public approbation of a Cheysuli warrior is the first step in restoring the Lion Throne to the sovereignty of the Cheysuli, required by the prophecy, and sows the seeds of civil unrest.

Legacy of the Sword focuses on Donal’s slow assumption of power within Homana, and his personal assumption of his role in the prophecy. Because by clan custom a warrior is free to take both wife and mistress, Donal has started a Cheysuli family even though he will one day have to marry Carillon’s daughter to cement his right to the Lion Throne. By his Cheysuli mistress he has two children, Ian and Isolde; by Aislinn, Carillon’s daughter, he eventually sires a son who will become his heir. But the marriage is rocky immediately; in addition to the problems caused by a second family, Donal’s Homanan wife is also under the magical influence of her mother, Electra, who is mistress to Tynstar. Problems are compounded by the son of Tynstar and Electra, Strahan, who has his father’s powers in full measure. On Carillon’s death Donal inherits the Lion, naming his legitimate son, Niall, to succeed him. But to further the prophecy he marries his sister, Bronwyn, to Alaric of Atvia, lord of an island kingdom. Bronwyn is later killed by Alaric accidentally while in lir-shape, but lives long enough to give birth to a daughter, Gisella, who is mad.

In Track of the White Wolf, Donal’s son Niall is a young man caught between two worlds. To the Homanans, fearful of Cheysuli power and intentions, he is worthy only of distrust, the focus of their discontent. To the Cheysuli he is an “unblessed” man, because even though far past the age for it, Niall has not linked with his animal. He is therefore a lirless man, a warrior with no power, and such a man has no place within the clans. His Cheysuli half-brother is his liege man, fully “blessed,” and Ian’s abilities serve to add to Niall’s feelings of inferiority.

Niall is meant to marry his half-Atvian cousin, Gisella, but falls in love with the princess of a neighboring kingdom, Deirdre of Erinn. Lirless, and with Gisella under the influence of Tynstar’s Ihlini daughter, Lillith, Niall falls prey to sorcery. Eventually he links with his lir and assumes the full range of Cheysuli powers, but he pays for it with an eye. His marriage to Gisella is disastrous, but two sets of twins are born—Brennan and Hart, Corin and Keely—which gives Niall the opportunity to extend his range of influence via betrothal alliances. He banishes Gisella to Atvia after he foils an Ihlini plot involving her, and then settles into life with his mistress, Deirdre of Erinn, who has already borne Maeve, his illegitimate daughter.

A Pride of Princes tells the story of each of Niall’s three sons. Brennan, the eldest, will inherit Homana and has been betrothed to Aileen, Deirdre’s niece, to add a heretofore unknown bloodline to the prophecy. Brennan’s twin, Hart, is Prince of Solinde, a compulsive gambler whose addiction results in a tragic accident involving all three of Niall’s sons. Hart is banished to Solinde for a year, and the rebellious youngest son, Corin, to Atvia. Brennan is tricked into siring a child on an Ihlini-Cheysuli woman; Hart loses a hand and nearly his life in a Solindish plot; in Erinn, Corin falls in love with Brennan’s bride, Aileen, before going to Atvia. One by one each is captured by Strahan, Tynstar’s son, who intends to turn Niall’s sons into puppet-kings so he can rule through them. All three manage to escape, but not after each has been made to recognize particular strengths and weaknesses.

For Keely, sister to Niall’s sons, things are different. In Daughter of the Lion, Keely herself is caught up in the machinations of politics, evil sorcery, and her own volatile emotions. Trained from childhood in masculine pursuits such as weaponry, Keely prefers the freedom of choice and lifestyle, and as both are threatened by the imminent arrival of her betrothed, Sean of Erinn, she fights to maintain her sense of self in a world ruled by men. She is therefore ripe for rebellion when a strong-minded, powerful Erinnish brigand—and possible murderer—enters her life.

But Keely’s battles are increased tenfold when Strahan chooses her as his next target. Betrayed, trapped, and imprisoned on the Crystal Isle, Keely is forced through sorcery into a liaison with the Ihlini that results in pregnancy. But before the child can be born, Keely escapes with the aid of the Ihlini bard, Taliesin. On her way home she meets the man believed to be her betrothed, and realizes not only must she somehow rid herself of the unwanted child, but must also decide which man she will have—thief or prince—in order to be a true Cheysuli in service to the prophecy.

Prologue

He was small, so very small, but desperation lent him strength. The need lent him strength, even though fright and tension threatened to undermine it. He placed small hands on the hammered silver door and pushed as hard as he could, grunting with the effort; pushing with all his might.

The door opened slightly. Then fell back again, scraping, as his meager strength failed.

“No,” he muttered aloud between clenched teeth. “No, I will not let you.”

He shoved very hard again. This time he squeezed into the opening before the door could shut. When it shut, it shut on him; gasping shock and fright, Aidan thrust himself through. His sleeping robe tore, but he did not care. It did not matter. He was in at last.

Once in, he froze. The Great Hall was cavernous. Darker than night—a thick, heavy blackness trying to squash him flat. Darkness and something calling to him.

He would not be squashed. He would not—and yet his belly knotted. Who was he to do this? Who was he to come to his grandsire’s Great Hall, to confront the Lion Throne?

Small hands tugged at hair, twisting a lock through fingers. Black hair by night; by day a dark russet, red in the light of the sun. He peered the length of the hall, feeling cold stone beneath his feet. His mother would have told him to put on his slippers. But the need had been so great that nothing else mattered but that he confront the Lion, and the thing in the Lion’s lap.

He shivered. Not from cold: from fear.

Compulsion drove him. Aidan moaned a little. He wanted to leave the hall. He wanted to turn his back on the Lion, the big black beast who waited to devour him. But the need, so overwhelming, would not let him.

No candles had been left lighted. The firepit coals glowed only vaguely. What little moon there was shone fitfully through the casements, its latticed light distorted by stained glass panes.

If only he could see.

No. He knew better. If he could see the Lion, he would fear it more.

Or would he? The light of day was no better. The Lion still glared, still bared wooden teeth. Now he could barely see it, acrouch on the marble dais. Could it see him?

Aidan bit a finger. Bowels turned to water; he wanted the chamber pot. But he was prince and also Cheysuli. If he retreated now, he would dishonor the blood in his veins.

But, oh, how he wanted to leave!

Aidan rocked a little. “Jehana…” he whispered, not knowing that he spoke.

In the darkness, the Lion waited.

So did something else.

Aidan drew in a strangled breath in three gulping inhalations very noisy in the silence. Pressure in his bladder increased. He bit into his finger, then slowly took a step.

One. Then two. Then three. He lost count of them all. But eventually all the steps merged and took him the length of the hall, where he stood before the Lion. He looked at eyes, teeth, nostrils. All of it wood, all of it. He was made of flesh. He would rule the Lion.

With effort, Aidan looked into the lap. In dim light, something glowed.

It was a chain, made of gold. Heavy, hammered gold, alive with promises. More than wealth, or power: the chain was heritage. His past, and his future: legacy of the gods. He reached for it, transfixed, wanting it, needing it, knowing it was for him; but when his trembling hand closed over a link the size of a large man’s wrist, the chain shapechanged to dust.

He cried out. Urine stained his nightrobe. Shame flooded him, but so did desperation. It had been right there; now there was nothing. Nothing at all remained. The dust—and the chain—was gone.

He did not want to cry. He did not intend to cry, but the tears came anyway. Which made him cry all the harder, ashamed of his emotion. Ashamed of his loss of control. Of his too-Homanan reaction; Cheysuli warriors did not cry. Grief was not expressed.

But he was more than merely Cheysuli. And no one let him forget.

Only one more bloodline needed. One more outcross required, and the prophecy was complete. But even he, at six, knew how impossible it was. He had heard it often enough in the halls of Homana-Mujhar.

No Cheysuli warrior will ever lie down with an Ihlini and sire a child upon her.

But even he, a boy, knew better. A Cheysuli warrior had; in fact, two had: his grandsire’s brother, Ian, and his own father, the Prince of Homana, who one day would be Mujhar.

Even at six, he knew. And knew what he was meant for; what blood ran in his veins. But it was all very confusing, and he chose to leave it so.

Grief renewed itself. I want my chain.

But the chain—his chain—had vanished.

A small ferocity was born: I want my CHAIN—

One of the doors scraped open. Aidan twitched and swung around unsteadily, clutching the sodden nightrobe in both hands. It was his mother, he knew. Who else would come looking for a boy not in his bed? And she would see, she would know—

“Aidan? Aidan—what are ye doing here? ’Tis far past your bedtime!”

Shame made him hot. He fought tears and trembling.

She was white-faced, distraught, though trying to hide it. He knew what she felt; could feel it, as if her skin was his. But she tried so hard to hide it.

The familiar lilt of Erinn echoed in the Great Hall. “What are ye doing, my lad? Paying homage to the Lion?” Aileen’s laugh was forced. “’Twill be your beastie, one day—there’s no need for you to come in the night to see it!”

She meant well, he knew. She always meant well. But he sensed her fear, her anguish, beneath forced cheerfulness.

She hurried the length of the hall, gathering folds of a heavy robe. By the doors stood a servant holding a lamp. Light glowed in the hall. The Lion leaped out of the shadows.

Aidan fell back, thrusting up a warding arm, then realized it was no more than it ever was: a piece of wood shaped by man. And then his mother was beside him, asking him things fear distorted, until she gathered the reins of her worry and knotted them away.

She saw his hands doubled up in a soaked nightrobe. She saw the urine stain. Anguish flared anew—he felt it most distinctly, like a burning band thrust into his spirit—but she said nothing of it. She merely knelt down at his side, putting a hand on his shoulder. “Aidan—why are you here? Your nurse came, speaking of a nightmare…but when I came, you were gone. What are you doing here?”

He looked up into her face as she knelt down next to him. Into eyes green as glass; green as Erinnish turf. “’Tis gone,” he told her plainly, unconsciously adopting her accent.

She wore blue velvet chamber robe over white linen night-shift. Her hair was braided for sleeping: a single thick red plait, hanging down her back. “What’s gone, my lad?”

“The chain,” he explained, though he knew she would not understand. No one understood; no one could understand.

Sudden anguish was overwhelming. He craved reassurance as much as understanding. The former he could get. As the hated tears renewed themselves, he went willingly into her arms.

She pressed her cheek against his head, twining arms around small shoulders to still the wracking sobs. “Oh, Aidan, Aidan…’twas only a dream, my lad…a wee bit of a dream come to trouble your sleep. There’s no harm in it, I promise, but you mustn’t be thinking ’tis real.”

“’Twas real,” he insisted, crying hard into her shoulder. “’Twas real—I swear…and the Lion—the Lion meant to eat me—”

“Aidan, no. Oh, my sweet bairn, no. There’s naught to the Lion’s teeth but bits of rotting wood.”

“’Twas real—’twas there—”

“Aidan, hush—”

“It woke me up, calling…” He drew his head away so he could see her face, to judge what she thought. “It wanted me to come—”

“The Lion?”

Fiercely, he shook his head. “Not the Lion—the chain—”

“Oh, Aidan—”

She did not believe him. He hurled himself against her, trembling from a complex welter of fear, anguish, insistence: he needed her to believe him. She was his rock, his anchor—if she did not believe him—

In Erinnish, she tried to soothe him. He needed her warmth, her compassion, her love, but he was aware, if distantly, he also required something more. Something very real, no matter what she said: the solidity of the chain in his small-fingered child’s hands, because it was his tahlmorra. Because he knew, without knowing why, the golden links in his dreams bound him as fully as his blood.

A sound: the whisper of leather on stone, announcing someone’s presence. Pressed against his mother, Aidan peered one-eyed over a velveted shoulder and saw his father in the hall. His tall, black-haired father with eyes undeniably yellow, feral as Aidan’s own; a creature of the shadows as much as flesh and bone. Brennan’s dress was haphazard and the black hair mussed. Alarm and concern stiffened the flesh of his face.

“The nursemaid came—what is wrong?”

Aidan felt his mother turn on her knees even as her arms tightened slightly. “Oh, naught but a bad dream. Something to do with the Lion.” Forced lightness. Forced calm. But Aidan read the nuances. For him, a simple task.

The alarm faded as Brennan walked to the dais. The tension in his features relaxed. “Ah, well, there was a time it frightened me.”

Aidan did not wait. “I wanted the chain, jehan. It called me. It wanted me…and I needed it.”

Brennan frowned. “The chain?”

“In the Lion. The chain.” Aidan twisted in Aileen’s arms and pointed. “’Twas there,” he insisted. “I came to fetch it because it wanted me to. But the Lion swallowed it.”

Brennan’s smile was tired. Aidan knew his father sat up late often to discuss politics with the Mujhar. “No one ever said the Lion does not hunger. But it does not eat little boys. Not even little princes.”

Vision blurred oddly. “It will eat me…”

“Aidan, hush. ’Tis fanciful foolishness,” Aileen admonished, rising to stand. “We’ll be having no more of it.”

A dark-skinned, callused hand was extended for Aidan to grasp. Brennan smiled kindly. “Come, little prince. Time you were safe in bed.”

It was shock, complete and absolute. They do not believe me, either of them—

His mother and his father, so wise and trustworthy, did not believe him. Did not believe their son.

He gazed blindly at the hand still extended from above. Then he looked into the face. A strong, angular face, full of planes and hollows; of heritage and power.

His father knew everything. But if his father did not believe him.

Aidan felt cold. And hollow. And old. Something inside flared painfully, then crumbled into ash.

They will think I am LYING.

It hurt very badly.

“Aidan.” Brennan wiggled fingers. “Are you coming with me?”

A new resolve was born. If I tell them nothing, they cannot think I am lying.

“Aidan,” Aileen said, “go with your father. ’Tis time you were back in bed.”

Where I might dream again.

He shivered. He gazed up at the hand.

“Aidan,” Aileen murmured. Then, in a flare of stifled impatience, “Take him to bed, Brennan. If he cannot be taking himself.”

That hurt, too.

Neither of them believe me.

The emptiness increased.

Will anyone believe me?

“Aidan,” Brennan said. “Would you have me carry you?”

For a moment, he wanted it. But the new knowledge was too painful. Betrayal was not a word he knew, but was beginning to comprehend.

Slowly he reached out and took the hand. It was callused, large, warm. For a moment he forgot about the betrayal: the hand of his father was a talisman of power; it would chase away the dreams.

Aidan went with his father, followed by his mother. Behind them, in the darkness, crouched the Lion Throne of Homana, showing impotent teeth.

He clutched his father’s hand. Inside his head, rebelling, he said it silently: I want my chain.

Gentle fingers touched his hair, feathering it from his brow. “’Twas only a dream,” she promised.

Foreboding knotted his belly. But he did not tell her she lied. He wanted his mother to sleep, even if he could not.

PART I

One

Deirdre’s solar had become a place of comfort to all of them. Of renewal. A place where rank did not matter, nor titles, nor the accent with which one spoke: Erinnish, Cheysuli, Homanan. It was, Aileen felt, a place where all of them could gather, regardless of differing bloodlines, to share the heavy, unspoken bonds of heritage. It had nothing to do with magic, breeding, or homeland. Only with the overriding knowledge of what it was to rule.

She knew what Keely would say, had said, often enough, phrased in many different—and explicit—ways. That women had no place in the male-dominated succession lining up for the Lion Throne. But Aileen knew better. Keely would not agree—she seldom agreed with anything concerning the disposition of women—but it was true. Women did have a place in the line of succession. As long as kings needed queens to bear sons for the Lion, women would have a place.

Not the place Keely—or others—might want, but it was something nonetheless. It made women important, if for womb instead of brain.

Aileen’s womb had given Homana one son. Twin boys, enough to shore up Aidan’s tenuous place in the succession, were miscarried; the ordeal had left her barren. She was, therefore, a princess of precarious renown, and potentially threatened future. Brennan would not, she knew, set her aside willingly—he had made that clear—but there were others to be reckoned with besides the Prince of Homana. He was only a prince; kings bore precedence. And while the Mujhar showed no signs of concern regarding her son’s odd habits, she knew very well even Niall was not the sole arbiter. There was also the Homanan Council. She was the daughter of a king, albeit the island was small; nonetheless, she understood the demands of a kingship. The demands of a council.

Only one son for Homana. One son who was—different.

She shivered. The solar was comfortable, but her peace of mind nonexistent. It was why she had gone to Deirdre.

Aileen stood rigidly before the casement in the solar with sunlight in her hair, setting it ablaze. A wisp drifted near her eyes; distracted, she stripped it back. The gesture was abrupt, impatient, lacking the grace she had mastered after twenty-four years as Princess of Homana; twenty-four years as her aunt’s protégée, in blood as well as deportment.

She folded arms beneath her breasts and hugged herself, hard. “I’ve tried,” she said in despair. “I’ve tried to understand, to believe ’twould all pass…but there’s no hiding from it now. It started in childhood…he thinks we’re not knowing…he believes he’s fooled us all, but servants know the truth. They always know the truth—d’ye think they’d keep it secret?” Her tone now echoed the rumors. “The heir to Homana rarely spends a whole night in sleep—and he goes to talk to the Lion, to rail against a chair…” She let it trail off, then hugged herself harder. “What are we to do? I think he’ll never be—right.” Her voice broke on the last word. With it her hard-won composure; tears welled into green eyes. “What are we to do? How can he hold the throne if everyone thinks him mad?”

Deirdre of Erinn, seated near the window with lap full of yarn and linen, regarded Aileen with compassion and sympathy. At more than sixty years of age she was no longer young—brass-blonde hair was silver, green eyes couched in creases, the flesh less taut on her bones—but her empathy was undiminished even if beauty was. She knew what it was like to fear for a child; she had borne the Mujhar a daughter. But Maeve, for all her troubles, had never been like Aidan. Her niece’s fears were legitimate. They all realized Aidan was—different.

Deirdre knew better than to attempt to placate Aileen with useless platitudes, no matter how well-meant. So she gave her niece the truth: “’Twill be years before Aidan comes close to inheriting. There is Brennan to get through first, and Niall is nowhere near dying. Don’t be borrowing trouble, or wishing it on others.”

Aileen made a jerky gesture meant to dispel the bad-wishing, a thing Erinnish abhorred. “No, no…gods willing—” she grimaced “—or their eternal tahlmorras—Aidan will be old…but am I wrong to worry? ’Twas one thing to dream as a child—he’s a grown man now, and the dreams are worse than ever!”

Deirdre’s mouth tightened. “Has he said nothing of it? You used to be close, you and Aidan—and he as close to Brennan. What has he said to you?”

Aileen’s expulsion of breath was underscored with bitterness. “Aidan? Aidan says nothing. Aye, once we were close—when he was so little…but now he says nothing. Not to either of us. ’Tis as if he cannot trust us—” She pressed the palms of her hands against temples, trying to massage away the ache. “If I say aught to him—if I ask him what troubles him, he tells me nothing. He lies to me, Deirdre! And he knows I know it. But does it change his answer? No, not his…he is, if nothing else, stubborn as a blind mule.”

“Aye, well, he’s getting that from both sides of his heritage,” Deirdre’s smile was kind. “He is but twenty-three. Young men are often secretive.”

“No—not like Aidan.” Aileen, pacing before the window, lifted a hand, then let it drop to slap against her skirts. “The whole palace knows it…the whole city knows it—likely all of Homana.” She stopped, swung to face Deirdre, half-sitting against the casement sill. “Some of them go so far as to say he’s mad, mad as Gisella.”

“Enough!” Deirdre said sharply. “Do you want to give fuel to such talk? You’re knowing as well as I there’s nothing in that rumor. He could no more inherit insanity than I did, or you.” She sat straighter in her chair, unconscious of creased linen. “He’s Erinnish, too, as well as Cheysuli…how d’ye know he’s not showing a bit of our magic? There’s more than a little in the House of Eagles—”

Aileen cut her off. “Oh, aye, I know…but the Cheysuli is so dominant I doubt our magic can show itself.”

Deirdre lifted an eyebrow. “That’s not so certain,

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...