- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

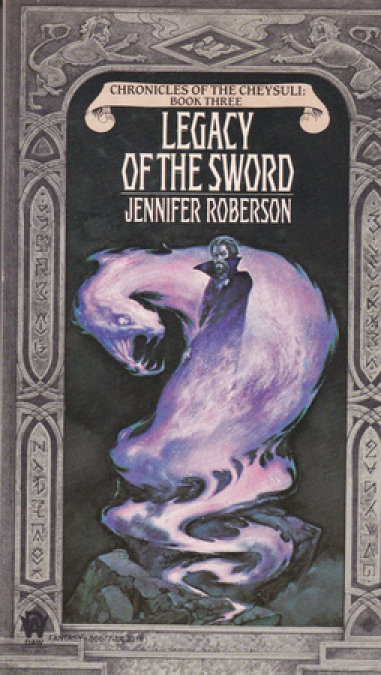

The third book in the Chronicles of the Cheysuli continues a tale of magical warriors and shapeshifters as they battle the sorcerers that threaten their existence

For decades, the magical race of shapeshifters called the Cheysuli have been feared and hated exiles in their own land, a land they rightfully should rule. Victims of a vengeful monarch's war of annihilation and a usurper king's tyrannical reign, the Cheysuli clans have nearly vanished from the world.

Now, in the aftermath of the revolution which overthrew the hated tyrant, Prince Donal is being trained as the first Cheysuli in generations to assume the throne. But will he be able to overcome the prejudice of a populace afraid of his special magic and succeed in uniting the realm in its life and death battle against enemy armies and evil magicians?

Release date: April 1, 1986

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Legacy of the Sword

Jennifer Roberson

DAW titles by Jennifer Roberson

THE SWORD-DANCER SAGA

SWORD-DANCER

SWORD-SINGER

SWORD-MAKER

SWORD-BREAKER

SWORD-BORN

SWORD-SWORN

SWORD-BOUND

CHRONICLES OF THE CHEYSULI

SHAPECHANGERS

THE SONG OF HOMANA

LEGACY OF THE SWORD

TRACK OF THE WHITE WOLF

A PRIDE OF PRINCES

DAUGHTER OF THE LION

FLIGHT OF THE RAVEN

A TAPESTRY OF LIONS

THE GOLDEN KEY

(with Melanie Rawn and Kate Elliott)

ANTHOLOGIES

(as editor)

RETURN TO AVALON

HIGHWAYMEN: ROBBERS AND ROGUES

LEGACY

OF THE SWORD

JENNIFER ROBERSON

Copyright ©, 1986 by Jennifer Roberson O’Green.

All Rights Reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-101-65109-4

Cover art by Julek Heller.

DAW Book Collectors No. 669.

The scanning, uploading and distribution via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage the electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author's rights is appreciated.

First Printing, April 1986

Table of Contents

Hondarth did not resemble a city so much as a flock of sheep pouring down over lilac heather toward the glass-gray ocean beyond. From atop the soft, slope-shouldered hills surrounding the scalloped bay, gray-thatched cottages appeared to huddle together in familial affection.

Once, Hondarth had been no more than a small fishing village; now it was a thriving city whose welfare derived from all manner of foreign trade as well as seasonal catches. Ships docked daily and trade caravans were dispatched to various parts of Homana. And with the ships came an influx of foreign sailors and merchants; Hondarth had become almost cosmopolitan.

The price of growth, Donal thought. But I wonder, was Mujhara ever this—haphazard?

He smiled. The thought of the Mujhar’s royal city—with the palace of Homana-Mujhar a pendent jewel in a magnificent crown—as ever being haphazard was ludicrous. Had not the Cheysuli originally built the city the Homanans claimed for themselves?

Still smiling, Donal guided his chestnut stallion through the foot traffic thronging the winding street. Few cities know the majesty and uniformity of Mujhara. But I think I prefer Hondarth, if I must know a city at all.

And he did know cities. He knew Mujhara very well indeed, for all he preferred to live away from it. He had, of late, little choice in his living arrangements.

Donal sighed. I think Carillon will see to it my wings are clipped, my talons filed…or perhaps he will pen me in a kennel, like his hunting dogs.

And who would complain about a kennel as fine as Homana-Mujhar?

The question was unspoken, yet clearly understood by Donal. He had heard similar comments from others, many times before. Yet this one came not from any human companion but from the wolf padding at the stallion’s side.

Padding, not slinking; not as if the wolf avoided unwanted contact. He did not stalk, did not hunt, did not run from man or horse. He paced the stallion like a well-tamed hound accompanying a beloved master, but the wolf was no dog. Nor was he particularly tame.

He was not a delicate animal, but spare, with no flesh beyond that which supported his natural strength and quickness. The brassy sunlight of a foggy coastal late afternoon tipped his ruddy pelt with the faintest trace of bronze. His eyes were partially lidded, showing half-moons of brown and black.

I would complain about the kennel regardless of its aspect, Donal declared. So would you, Lorn.

An echo of laughter crossed the link that bound man to animal. So I would, the wolf agreed. But then Homana-Mujhar will be kennel to me as well as to you, once you have taken the throne.

That is not the point, Donal protested. The point is, Carillon begins to make more demands on my time. He takes me away from the Keep. Council meetings, policy sessions…all those boring petition hearings—

But the wolf cut him off. Does he have a choice?

Donal opened his mouth to answer aloud, prepared to contest the question. But chose to say nothing, aware of the familiar twinge of guilt that always accompanied less than charitable thoughts about the Mujhar of Homana. He shifted in the saddle, resettled the reins, made certain the green woolen cloak hung evenly over his shoulders…ritualized motions intended to camouflage the guilt; but they emphasized it instead.

And then, as always, he surrendered the battle to the wolf.

There are times I think he has a choice in everything, lir, Donal said with a sigh. I see him make decisions that are utterly incomprehensible to me. And yet, there are times I almost understand him…Almost… Donal smiled a little, wryly. But most of the time I think I lack the wit and sense to understand any of Carillon’s motives.

As good a reason as any for your attendance at council meetings, policy sessions, boring petition hearings….

Donal scowled down at the wolf. Lorn sounded insufferably smug. But arguing with his lir accomplished nothing—Lorn, like Carillon, always won the argument.

Just like Taj. Donal looked into the sky for the soaring golden falcon. As always, I am outnumbered.

You lack both wit and sense, and need the loan of ours. Taj’s tone was different within the threads of the link. The resonances of lir-speech were something no Cheysuli could easily explain because even the Old Tongue lacked the explicitness required. Donal, like every other warrior, simply knew the language of the link in all its infinite intangibilities. But only he could converse with Taj and Lorn.

I am put in my place. Donal conceded the battle much as he always did—with practiced humility and customary resignation; the concession was nothing new.

* * *

The tiny street gave out into Market Square as did dozens of others; Donal found himself funneled into the square almost against his will, suddenly surrounded by a cacophony of shouts and sing-song invitations from fishmongers and streethawkers. Languages abounded, so tangled the syllables were indecipherable. But then most he could not decipher anyway, being limited to Homanan and the Old Tongue of the Cheysuli.

The smell struck him like a blow. Accustomed to the rich earth odors of the Keep and the more subtle aromas of Mujhara, Donal could not help but frown. Oil. The faintest tang of fruit from clustered stalls. A hint of flowers, musk and other unknown scents wafting from a perfume-merchant’s stall. But mostly fish. Everywhere fish—in everything; he could not separate even the familiar smell of his leathers, gold and wool from the pervasive odor of fish.

The stallion’s gait slowed to a walk, impeded by people, pushcarts, stalls, booths, livestock and, occasionally, other horses. Most people were on foot; Donal began to wish he were, if only so he could melt into the crowd instead of riding head and shoulders above them all.

Lorn? he asked.

Here, the wolf replied glumly, nearly under the stallion’s belly. Could you not have gone another way?

When I can find a way out of this mess, I will. He grimaced as another rider, passing too close in the throng, jostled his horse. Knees collided painfully. The man, swearing softly beneath his breath as he rubbed one gray-clad knee, glanced up as if to apologize.

But he did not. Instead he stared hard for a long moment, then drew back in his saddle and spat into the street. “Shapechanger!” he hissed from between his teeth, “go back to your forest bolt-hole! We want none of your kind here in Hondarth!”

Donal, utterly astonished by the reaction, was speechless, so stunned was he by the virulence in words and tone.

“I said, go back!” the man repeated. His face was reddened by his anger. A pock-marked face, not young, not old, but filled with violence. “The Mujhar may give you freedom to stalk the streets of Mujhara in whatever beast-form you wear, but here it is different! Get you gone from this city, shapechanger!”

No. It was Lorn, standing close beside the stallion. What good would slaying him do, save to lend credence to the reasons for his hatred?

Donal looked down and saw how his right hand rested on the gold hilt of his long-knife. Carefully, so carefully, he unclenched his teeth, took his hand away from his knife and ignored the roiling of his belly.

He managed, somehow, to speak quietly to the Homanan who confronted him. “Shaine’s qu’mahlin is ended. We Cheysuli are no longer hunted. I have the freedom to come and go as I choose.”

“Not here!” The man, dressed in good gray wool but wearing no power or rank markings, shook his dark brown head. “I say you had better go.”

“Who are you to say so?” Donal demanded icily. “Have you usurped the Mujhar’s place in Homana to dictate my comings and goings?”

“I dictate where I will, when it concerns you shapechangers.” The Homanan leaned forward in his saddle. One hand gripped the chestnut’s reins to hold Donal’s horse in place. “Do you hear me? Leave this place. Hondarth is not for such as you.”

Their knees still touched. Through the contact, slight though it was, Donal sensed the man’s tension; sensed what drove the other to such a rash action.

He is afraid. He does not do this out of a sense of justice gone awry, or any personal vendetta—he is simply afraid.

Frightened, men will do anything. It was Taj, circling in seeming idleness above the crowded square. Lir, be gentle with him.

After what he has said to me?

Has it damaged you?

Looking into brown, malignant eyes, Donal knew the other would not back down. He could not. Homanan pride was not Cheysuli pride, but it was still a powerful force. Before so many people—before so many Homanans and facing a dreaded Cheysuli—the man would never give in.

But if I back down, I will lose more than just my pride. It will make it that much more difficult for any warrior who comes into Hondarth.

And so he did not back down. He leaned closer to the man, which caused the Homanan to flinch back, and spoke barely above a whisper. “You are truly a fool to think you can chase me back into the forests. I come and go as I please. If you think to dissuade me, you will have myself and my lir to contend with.” A brief gesture indicated the hackled wolf and Taj’s attentive flight. “What say you to me now?”

The Homanan looked down at Lorn, whose ruddy muzzle wrinkled to expose sharp teeth. He looked up at Taj as the falcon slowly, so slowly, circled, descending to the street.

Lastly he looked at the Cheysuli warrior who faced him: a young man of twenty-three, tall even in his saddle; black-haired, dark-skinned, yellow-eyed; possessed of a sense of grace, confidence and strength that was almost feral in its nature. He had the look of intense pride and preparedness that differentiated Cheysuli warriors from other men. The look of a predator.

“I am unarmed,” the Homanan said at last.

Donal did not smile. “Next time you choose to offer insult to a Cheysuli, I suggest you do so armed. If I was forced to slay you, I would prefer to do it fairly.”

The Homanan released the stallion’s rein. He clutched at his own so violently the horse’s mouth gaped open, baring massive teeth in silent protest. Back, back…iron-shod hooves scraped against stone and scarred the cobbles. The man paid no heed to the people he nearly trampled or the collapse of a flimsy fruit stall as his mount’s rump knocked down the props. He completely ignored the shouts of the angry merchant.

But before he left the square he spat once more into the street.

Donal sat rigidly in his saddle and stared at the spittle marring a single cobble. He was aware of an aching emptiness in his belly. Slowly that emptiness filled with the pain of shock and outraged pride.

He is not worth slaying. But Lorn’s tone within the pattern sounded suspiciously wistful.

Taj, still circling, climbed back into the sky. You will see more of that. Did you think to be free of such things?

“Free?” Donal demanded aloud. “Carillon ended Shaine’s qu’mahlin!”

Neither lir answered at once.

Donal shivered. He was cold. He felt ill. He wanted to spit much as the Homanan had spat, wishing only to rid himself of the sour taste of shock.

“Ended,” he repeated. “Everyone in Homana knows Carillon ended the purge.”

Lorn’s tone was grim. There are fools in the world, and madmen; people driven by ignorant prejudice and fear.

Donal looked out on the square and slowly shook his head. Around him swarmed Homanans whom he had, till now, trusted readily enough, having little reason not to. But now, looking at them as they went about their business, he wondered how many hated him for his race without really understanding what he was.

Why? he asked his lir. Why do they spit at me?

You are the closest target. Taj told him. Not because of rank and title.

Homanan rank and title, Donal pointed out. Can they not respect that at least? It is their own, after all.

If you tell them who and what you are, Lorn agreed. Perhaps. But he saw only a Cheysuli.

Donal laughed a little, but there was nothing humorous in it. Ironic, is it not? That man had no idea I was the Prince of Homana—he saw a shapechanger, and spat. Knowing, maybe he would have shut his mouth, out of respect for the title. But others, other Homanans—knowing what Carillon has made me—resent me for that title.

A woman, passing, muttered of beasts and demons and made a ward-sign against the god of the netherworld. The sign was directed at Donal, as if she thought he was a servant of Asar-Suti.

“By the gods, the world has gone mad!” Donal stared after the woman as she faded into the crowded square. “Do they think I am Ihlini?”

No, Taj said. They know you are Cheysuli.

Let us get out of this place at once. But even as Donal said it, he felt and heard the smack of some substance against one shoulder.

And smelled its odor, also.

He turned in the saddle at once, shocked by the blatant attack. But he saw no single specific culprit, only a square choked with people. Some watched him. Others did not.

Donal reached back and jerked his cloak over one shoulder to see what had struck his back, though he thought he knew. He grimaced when he saw the residue of fresh horse droppings. In disgust he shook the cloak free of manure, then let the folds fall back.

We are leaving this square, he told his lir. Though I would prefer to leave this city entirely.

Donal turned his horse into the first street he saw and followed its winding course. It narrowed considerably, twisting down toward the sea among whitewashed buildings topped with thatched gray roofs. He smelled salt and fish and oil, and the tang of the sea beyond. Gulls cried raucously, white against the slate-gray sky, singing their lonely song. The clop of his horse’s hooves echoed in the narrow canyon of the road.

Do you mean to stop? Taj inquired.

When I find an inn—ah, there is one ahead. See the sign? The Red Horse Inn.

It was a small place, whitewashed like the others, its thatched roof worn in spots. The wooden sign, in the form of a crimson horse, faded, dangled from its bracket on a single strip of leather.

Here? Lorn asked dubiously.

It will do as well as another, provided I may enter. Donal felt the anger and sickness rise again, frustrated that even Carillon—with all that he had accomplished—had not been able to entirely end the qu’mahlin. But even as he spoke, Donal realized what the wolf meant; the Red Horse Inn appeared to lack refinement of any sort. Its two horn windows were puttied with grime and smoke, and the thatching stank of fish oil, no doubt from the lanterns inside. Even the white-washing was grayed with soot and dirt.

You are the Prince of Homana. That from Taj, ever vigilant of such things as princely dignity and decorum.

Donal smiled. And the Prince of Homana is hungry. Perhaps the food will be good. He swung off his mount and tied it to a ring in the wall provided for that purpose. Bide here with the horse. Let us not threaten anyone else with your presence.

You are going in. Lorn’s brown eyes glinted for just a moment.

Donal slapped the horse on his rump and shot the wolf a scowl. There is nothing threatening about me.

Are you not Cheysuli? asked Taj smugly as he settled on the saddle.

The door to the inn was snatched open just as Donal put out his hand to lift the latch. A body was hurled through the opening. Donal, directly in its path, cursed and staggered back, grasping at arms and legs as he struggled to keep himself and the other upright. He hissed a Cheysuli invective under his breath and pushed the body back onto its feet. It resolved itself into a boy, not a man, and Donal saw how the boy stared at him in alarm.

The innkeeper stood in the doorway, legs spread and arms folded across his chest. His bearded jaw thrust out belligerently. “I’ll not have such rabble in my good inn!” he growled distinctly. “Take your demon ways elsewhere, brat!”

The boy cowered. Donal put one hand on a narrow shoulder to prevent another stumble. But his attention was more firmly focused on the innkeeper. “Why do you call him a demon?” he asked. “He is only a boy.”

The man looked Donal up and down, brown eyes narrowing. Donal waited for the epithets to include himself, half-braced against another clot of manure—or worse—but instead of insults he got a shrewd assessment. He saw how the innkeeper judged him by the gold showing at his ear and the color of his eyes. His lir-bands were hidden beneath a heavy cloak, but his race—as always—was apparent enough.

Inwardly Donal laughed derisively. Homanans! If they are not judging us demons because of the shapechange, they judge us by our gold instead. Do they not know we revere our gold for what it represents, and not the wealth at all?

The Homanans judge your gold because of what it can buy them. Taj settled his wings tidily. The freedom of the Cheysuli.

The innkeeper turned his face and spat against the ground. “Demon,” he said briefly.

“The boy, or me?” Donal asked with exaggerated mildness, prepared for either answer. And prepared to make his own.

“Him. Look at his eyes. He’s demon-spawn, for truth.”

“No!” the boy cried. “I’m not!”

“Look at his eyes!” the man roared. “Tell me what you see!”

The boy turned his face away, shielding it behind one arm. His black hair was dirty and tangled, falling into his eyes as if he meant it to hide them. He showed nothing to Donal but a shoulder hunched as if to ward off a blow.

“Do you wish to come in?” the innkeeper demanded irritably.

Donal looked at him in genuine surprise. “You throw him out because you believe him to be a demon—because of his eyes—and yet you ask me in?”

The man grunted. “Has not the Mujhar declared you free of taint? Your coin is as good as any other’s.” He paused. “You do have coin?” His eyes strayed again to the earring.

Donal smiled in relief, glad to know at least one man in Hondarth judged him more from avarice than prejudice. “I have coin.”

The other nodded. “Then come in. Tell me what you want.”

“Beef and wine. Falian white, if you have it.” Donal paused. “I will be in in a moment.”

“I have it.” The man cast a lingering glance at the boy, spat again, then pulled the door shut as he went into his inn.

Donal turned to the boy. “Explain.”

The boy was very slender and black-haired, dressed in dark, muddied clothing that showed he had grown while the clothes had not. His hair hung into his face. “My eyes,” he said at last. “You heard the man. Because of my eyes.” He glanced quickly up at Donal, then away. And then, as if defying the expected reaction, he shoved the tangled hair out of his face and bared his face completely. “See?”

“Ah,” Donal said, “I see. And I understand. Merely happenstance, but ignorant people do not understand that. They choose to lay blame even when there is no blame to lay.”

The boy stared up at him out of eyes utterly unremarkable—save one was brown and the other a clear, bright blue.

“Then—you don’t think me a demon and a changeling?”

“No more than am I myself.” Donal smiled and spread his hands.

“You don’t think I’ll be putting a spell on you?”

“Few men have that ability. I doubt you are one of them.”

The boy continued to stare. He had the face of a street urchin, all hollowed and pointed and thin. His bony wrists hung out of tattered sleeves and his feet were shod in strips of battered leather. He picked at the front of his threadbare shirt with broken, dirty fingernails.

“Why?” he asked in a voice that was barely a sound. “Why is it you didn’t like hearing me called names? I could tell.” He glanced quickly at Donal’s face. “I could feel the anger in you.”

“Perhaps because I have had such prejudice attached to me,” Donal said grimly. “I like it no better when another suffers the fate.”

The boy frowned. “Who would call you names? And why?”

“For no reason at all. Ignorance. Prejudice. Stupidity. But mostly because, like you, I am not—precisely like them.” Donal did not smile. “Because I am Cheysuli.”

The mismatched eyes widened. The boy stiffened and drew back as if he had been struck, then froze in place. He stared fixedly at Donal and his grimy face turned pale and blotched with fear. “Shapechanger!”

Donal felt the slow overturning of his belly. Even this boy—

“Beast-eyes!” The boy made the gesture meant to ward off evil and stumbled back a single step.

Donal felt all the anger and shock swell up. Deliberately, with a distinct effort, he pushed it back down again. The boy was a boy, echoing such insults as he had heard, having heard them said of himself.

“Are you hungry?” Donal asked, ignoring the fear and distrust in the boy’s odd eyes.

The boy stared. “I have eaten.”

“What have you eaten—scraps from the innkeeper’s midden?”

“I have eaten!”

Anger gave way to regret. That even a boy such as this will fall prey to such absolute fear— “Well enough.” He said it more sharply than intended. “I thought to feed you, but I would not have you thinking I seek to steal your soul for my use. Perhaps you will find another innkeeper less judgmental than this one.”

The boy said nothing. After a long moment of shocked silence, he turned quickly and ran away.

In the morning, Donal found only one man willing to give him passage across the bay to the Crystal Isle, and even that man would not depart until the following day. So, left to his own devices, Donal stabled his horse and wandered down to the sea wall. He perched himself upon it and stared across the lapping waves.

He focused his gaze on the dark bump of land rising out of the Idrian Ocean a mere three leagues across the bay. Gods, what will Electra be like? What will she say to me?

He could hardly recall her, though he did remember her legendary beauty, for he had been but a young boy when Carillon had banished his Solindish wife for treason. Adultery too, according to the Homanans; the Cheysuli thought little of that charge, having no strictures against light women when a man already had a wife. In the clans, cheysulas, wives, and meijhas, mistresses, were given equal honor. In the clans, the birth of children was more important than what the Homanans called proprieties.

Treason. Aye, a man might call it that. Electra of Solinde, princess-born, had tried to have her royal Homanan husband slain so that Tynstar might take his place. Tynstar of the Ihlini, devotee of Asar-Suti, the god of the netherworld.

Donal suppressed a shudder. He knew better than to attribute the sudden chill he felt to the salty breeze coming inland from the ocean. No man, had he any wisdom at all, dismissed the Ihlini as simple sorcerers. Not when Tynstar led them.

He wishes to throw down Carillon’s rule and make Homana his own. For a moment he shut his eyes. It was so clear, so very clear as it rose up before his eyes from his memory: the vision of Tynstar’s servitors as they had captured his mother. Alix they had drugged, to control her Cheysuli gifts. Torrin, her foster father, they had brutally slain. And her son they had nearly throttled with a necklace of heavy iron.

Donal put a hand against his neck. He recalled it so well, even fifteen years later. As if it were yesterday, and I still a boy. But the yesterday had faded, his boyhood long outgrown.

He opened his eyes and looked again upon the place men called the Crystal Isle. Once it had been a Cheysuli place, or so the shar tahls always said. But now it was little more than a prison for Carillon’s treacherous wife.

The Queen of Homana. Donal grimaced. Gods, how could he stay wed to her? I know the Homanans do not countenance the setting aside of wives—it is even a part of their laws—but the woman is a witch! Tynstar’s meijha. He scrubbed a hand through his hair and felt the wind against his face. Cool, damp wind, filled with the scent of the sea. If he gave her a chance, she would seek to slay him again.

Taj wheeled idly in the air. Perhaps it was his tahlmorra.

Homanans have none. Not as we know it. Donal shook his head. They call it fate, destiny…saying they make their own without the help of the gods. No, the Homanans have no tahlmorra. And Carillon, much as I respect him, is Homanan to the bone.

There is that blood in you as well, returned the bird.

Aye. His mouth twisted. But I cannot help it, much as I would prefer to forget it altogether.

It makes you what you are, Taj said. That, and other things.

Donal opened his mouth to answer aloud, but Lorn urgently interrupted. Lir, there is trouble.

Donal straightened and swung his legs over the wall, rising at once. He looked in the direction Lorn indicated with his nose and saw a group of boys wrestling on the cobbles.

He frowned. “They are playing, Lorn.”

More than that. Lorn told him. They seek to do serious harm.

Taj drifted closer to the pile of scrambling bodies. The boy with odd eyes.

Donal grunted. “I am not one of his favorite people.”

You might become so, Lorn pointed out, if you gave him the aid he needs.

Donal cast the smug wolf a skeptical glance, but he went off to intervene. For all the boy had not endeared himself the day before, neither could Donal allow him to be beaten.

“Enough!” He stood over the churning mass of arms and legs. “Let him be!”

Slowly the mass untangled itself and he found five Homanan boys glaring up at him from the ground in various attitudes of fear and sullen resentment. The victim, he saw, regarded him in surprise.

“Let him be,” Donal repeated quietly. “That he was born with odd eyes signifies nothing. It could as easily have been one of you.”

The others got up slowly, pulling torn clothing together and wiping at grimy faces. Two of them drifted off quickly enough, tugging at two others who hastily followed, but the tallest, a red-haire

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...