- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

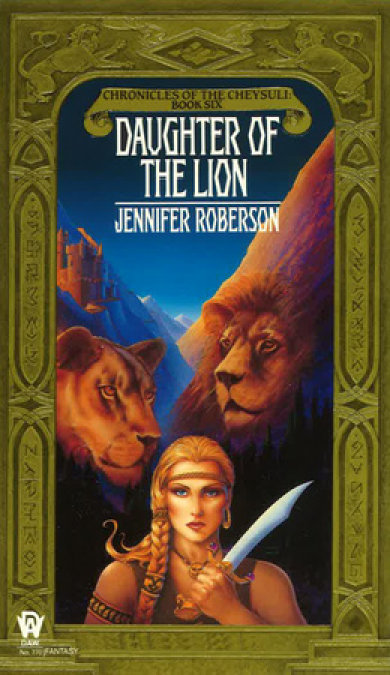

The sixth book in the Chronicles of the Cheysuli continues a tale of magical warriors and shapeshifters as they battle the sorcerers that threaten their existence

She is Keely, twin sister to Corin, and daughter to Niall, the ruler of Homana, and she alone has the power to shapechange into any form—a power akin to that of the Firstborn. Like her brothers, Keely has been chosen to play a crucial part in the Firstborn's prophecy.

Yet Keely is no weak pawn to be used in men's games of power and diplomacy. Trained alongside her brothers in the art of war, gifted with more of the old magic than most of her close kin, she will not easily give way even to Niall's commands, nor be forced against her will into an arranged marriage.

But others besides Keely's father have plans for her future. Stahan, the most powerful Ihlini sorcerer, is preparing a trap from which even one as magically-gifted as Keely may find no escape. And in the deepwood, another waits to challenge Keely—an outlaw fully as dangerous to her future freedom as Strahan is to her life....

Release date: February 7, 1989

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Daughter of the Lion

Jennifer Roberson

CHRONICLES

OF THE CHEYSULI:

BOOK SIX

DAUGHTER OF

THE LION

JENNIFER ROBERSON

Don’t miss JENNIFER ROBERSON’S monumental fantasies:

CHRONICLES OF THE CHEYSULI:

SHAPECHANGERS

THE SONG OF HOMANA

LEGACY OF THE SWORD

TRACK OF THE WHITE WOLF

A PRIDE OF PRINCES

DAUGHTER OF THE LION

FLIGHT OF THE RAVEN

A TAPESTRY OF LIONS

THE NOVELS OF TIGER AND DEL:

SWORD-DANCER

SWORD-SINGER

SWORD-MAKER

SWORD-BREAKER

SWORD-SWORN

SWORD-BORN

SWORD-BOUND

KARAVANS:

KARAVANS

DEEPWOOD

THE WILD ROAD

Table of Contents

The Chronicles of the Cheysuli:

An Overview

THE PROPHECY OF THE FIRSTBORN:

“One day a man of all blood shall unite,

in peace, four warring realms

and two magical races.”

Originally a race of shapechangers known as the Cheysuli, descendants of the Firstborn, Homana’s original race, held the Lion Throne, but increasing unrest on the part of the Homanans, who lacked magical powers and therefore feared the Cheysuli, threatened to tear the realm apart. The Cheysuli royal dynasty voluntarily gave up the Lion Throne so that Homanans could rule Homana, thereby avoiding fullblown internecine war.

The clans withdrew altogether from Homanan society save for one remaining and binding tradition: each Homanan king, called a Mujhar, must have a Cheysuli liege man as bodyguard, councillor, companion, dedicated to serving the throne and protecting the Mujhar, until such a time as the prophecy is fulfilled and the Firstborn rule again.

This tradition was adhered to without incident for nearly four centuries, until Lindir, the only daughter of Shaine the Mujhar, jilted her prospective bridegroom to elope with Hale, her father’s Cheysuli liege man. Because the jilted bridegroom was the heir of a neighboring king, Bellam of Solinde, and because their marriage was meant to seal an alliance after years of bloody war, the elopement resulted in tragic consequences. Shaine concocted a web of lies to salve his obsessive pride, and in so doing laid the groundwork for the annihilation of a race. Declared sorcerers and demons dedicated to the downfall of the Homanan throne, the Cheysuli were summarily outlawed and sentenced to immediate execution if found within Homanan borders.

Shapechangers begins the “Chronicles of the Cheysuli,” telling the tale of Alix, daughter of Lindir, once Princess of Homana, and Hale, once Cheysuli liege man to Shaine. Alix is an unknown catalyst bearing the Old Blood of the Firstborn, which gives her the ability to link with all lir and assume any animal shape at will. But Alix is raised by a Homanan and has no knowledge of her abilities, until she is kidnapped by Finn, a Cheysuli warrior who is Hale’s son by his Cheysuli wife, and therefore Alix’s half-brother. Kidnapped with her is Carillon, Prince of Homana. Alix learns the true power in her gifts, the nature of the prophecy which rules all Cheysuli, and eventually marries a warrior, Duncan, to whom she bears a son, Donal, and, much later, a daughter, Bronwyn. But Homana’s internal strife weakens her defenses. Bellam of Solinde, with his sorcerous aide, Tynstar the Ihlini, conquers Homana and assumes the Lion Throne.

In The Song of Homana, Carillon returns from a five-year exile, faced with the difficult task of gathering an army capable of overcoming Bellam. He is accompanied by Finn, who has assumed the traditional role of liege man. Aided by Cheysuli magic and his own brand of personal power, Carillon is able to win back his realm and restore the Cheysuli to their homeland by ending the purge begun by his uncle, Shaine, Alix’s grandfather. He marries Bellam’s daughter to seal peace between the lands, but Electra has already cast her lot with Tynstar the Ihlini, and works against her Homanan husband. Carillon’s failure to father a son forces him to betroth his only daughter, Aislinn, to Donal, Alix’s son, whom he names Prince of Homana. This public approbation of a Cheysuli warrior is the first step in restoring the Lion Throne to the sovereignty of the Cheysuli, required by the prophecy, and sows the seeds of civil unrest.

Legacy of the Sword focuses on Donal’s slow assumption of power within Homana, and his personal assumption of his role in the prophecy. Because by clan custom a warrior is free to take both wife and mistress, Donal has started a Cheysuli family even though he will one day have to marry Carillon’s daughter to cement his right to the Lion Throne. By his Cheysuli mistress he has two children, Ian and Isolde; by Aislinn, Carillon’s daughter, he eventually sires a son who will become his heir. But the marriage is rocky immediately; in addition to the problems caused by a second family, Donal’s Homanan wife is also under the magical influence of her mother, Electra, who is mistress to Tynstar. Problems are compounded by the son of Tynstar and Electra, Strahan, who has his father’s powers in full measure. On Carillon’s death Donal inherits the Lion, naming his legitimate son, Niall, to succeed him. But to further the prophecy he marries his sister, Bronwyn, to Alaric of Atvia, lord of an island kingdom. Bronwyn is later killed by Alaric accidentally while in lir-shape, but lives long enough to give birth to a daughter, Gisella, who is mad.

In Track of the White Wolf, Donal’s son Niall is a young man caught between two worlds. To the Homanans, fearful of Cheysuli power and intentions, he is worthy only of distrust, the focus of their discontent. To the Cheysuli he is an “unblessed” man, because even though far past the age for it, Niall has not linked with his animal. He is therefore a lirless man, a warrior with no power, and such a man has no place within the clans. His Cheysuli half-brother is his liege man, fully “blessed,” and Ian’s abilities serve to add to Niall’s feelings of inferiority.

Niall is meant to marry his half-Atvian cousin, Gisella, but falls in love with the princess of a neighboring kingdom, Deirdre of Erinn. Lirless, and with Gisella under the influence of Tynstar’s Ihlini daughter, Lillith, Niall falls prey to sorcery. Eventually he links with his lir and assumes the full range of Cheysuli powers, but he pays for it with an eye. His marriage to Gisella is disastrous, but two sets of twins are born—Brennan and Hart, Corin and Keely—which gives Niall the opportunity to extend his range of influence via betrothal alliances. He banishes Gisella to Atvia after he foils an Ihlini plot involving her, and then settles into life with his mistress, Deirdre of Erinn, who has already borne Maeve, his illegitimate daughter.

A Pride of Princes tells the story of each of Niall’s three sons. Brennan, the eldest, will inherit Homana and has been betrothed to Aileen, Deirdre’s niece, to add a heretofore unknown bloodline to the prophecy. Brennan’s twin, Hart, is Prince of Solinde, a compulsive gambler whose addiction results in a tragic accident involving all three of Niall’s sons. Hart is banished to Solinde for a year, and the rebellious youngest son, Corin, to Atvia. Brennan is tricked into siring a child on an Ihlini-Cheysuli woman; Hart loses a hand and nearly his life in a Solindish plot; in Erinn, Corin falls in love with Brennan’s bride, Aileen, before going to Atvia. One by one each is captured by Strahan, Tynstar’s son, who intends to turn Niall’s sons into puppet-kings so he can rule through them. All three manage to escape, but not after each has been made to recognize particular strengths and weaknesses.

PART I

One

I was aware of eyes, watching me. Marking every step, every feint, my every riposte with the sword. Thinking, no doubt, I was mad; or did she wish she were in my place?

She had come before to watch me practice against the arms-master. Saying nothing, sitting quietly on a bench with heavy skirts spilling over her legs.

Before, it had not touched me, because I can be deaf and blind when I choose, so focused on the weapons. But this time it did. It reached out and touched me, and held me, with a new intensity.

In the eyes I saw desperation.

It was enough to pierce my concentration. Enough to get me killed, had it been anything but practice. As it was, Griffon’s blade tip slid easily by my guard and lodged itself, but gently, in the buckle of my belt.

“Dead,” he said calmly. “On your feet, but dead. And all your royal blood spilling out of those proud Cheysuli veins.”

Ordinarily I might have cursed him cheerfully, or retorted in kind, or made him try me again. But I did not, this time, because of the eyes that watched in such mute, distinct despair.

“Dead,” I agreed, and left him to gape in surprise as I walked past him to the woman.

She watched me come in silence, saying nothing with her mouth but screaming with her eyes. Green Erinnish eyes, born of an island kingdom very far from my own. But born into similar circumstances; bound by similar rules.

Though foreigners, we were kin. She had married my brother. I would marry hers.

Aileen of Erinn, now Princess of Homana, looked up at me as I stopped. Standing, we are similar in height; Cheysuli are taller than other races, but she comes of the House of Eagles, where men are often giants. But she is red-haired to my tawny, green-eyed to my blue. Equally outspoken, but without knowing the frustration I so often faced, because we wanted different things.

But now, she did not stand. She sat solidly on the bench, as if weighted by stone, with both hands clasped over her belly. Looking at her, I knew.

“By all the gods,” I said, “he has you breeding again!”

I had not meant it to come out so baldly, not to Aileen, whom I liked, and whom I preferred not to harm with hasty words. But I am not a person who thinks much before speaking, being ruled by temper and tongue; inwardly I cursed myself as I saw the flinch in her eyes.

And then her chin came up. I saw the line of her jaw harden, that strong Erinnish jaw, and knew for all she was wife to the Prince of Homana, he did not precisely rule her.

But then, being Brennan, I knew he would not try.

Aileen smiled a little, though one corner curved down crookedly. “In Erinn, bairns often follow the bedding. ’Tis the same in Homana, I think.”

I glanced over my shoulder at Griffon, due more honor than I gave him, but I was thinking of Aileen, and of things better kept private. “You may go,” I told him. “But come again tomorrow, at the same hour.”

Briefly, so briefly, there was a glint of something in brown eyes, but hidden instantly. I regretted my tone, but did not know what I might say to lessen the insult, since it was already given. He was far more than servant, being my father’s personal arms-master, and therefore in service to a king. And he owed no service to me, since only men are trained in the arts of war. He had agreed to train the Mujhar’s daughter only because he had lost a wager. In winning it, I had won him, and all that he could teach.

He cleaned his sword, sheathed it, bowed to Aileen and left. Giving her the courtesy he might have given me, had I been deserving of it. But for now, Aileen’s welfare was more important than Griffon’s feelings.

“He might have waited,” I said curtly. “He has a son already, and you nearly dead of that.” Grimly I caught up a soft cloth, cleaned the blade, drove it home into its sheath. “You have been wed but eighteen months, and a child of it already. Now there will be another?” I shook my head, speaking through my teeth. It was their business, not mine, but I could not help myself; Brennan and I are not, always, friends. “Aileen, he gives you no time—”

“’Twas not entirely up to him,” she told me sharply, giving me back my tone but in her Erinnish lilt. “D’ye think I had no say in the matter? D’ye think I’d let him take me against my will, or that he would try?” Aileen rose, absently shaking the rucked up folds out of her skirts. “Are ye forgetting, then, that women can want the bedding, too?”

It silenced me, as she meant it to. Aileen and I are close, nearly kinspirits, and she knows how strongly I feel about women being made to do certain things merely because they are women. She knows also I have little interest in bedding, being more concerned with freedom. In body as well as in mind.

“He might have waited,” I said again. “And you might have let him.”

She smiled. Aileen’s smile lights up a hall; it lighted the chamber now. “He might have,” she agreed, “and I might have, as well. But we were neither of us thinking of anything more than the moment’s pleasure…’twill come to you, one day, no matter what you think.”

I turned away from her and strode across to a sword rack, put away the sheathed blade. I felt the rigidity in my back; tried to loosen it even as I tried to force my tone into neutrality. “When will it be born?”

“Six months’ time,” she said. “And ‘it’ will be a ‘they.’”

I jerked around and stared at her. “Two?”

“Aye, so the physicians say.” Aileen smiled again, speaking easily. “A family trait, I’m told. First Brennan and Hart, then you and Corin. And now—?” She shrugged. “We’ll be seeing what we see.”

She did it well, I thought. Only her eyes betrayed her. “Two,” I repeated. “You nearly died of Aidan, and he was only one.”

Aileen shrugged again. “I’m larger, now, from Aidan. It should be easier this time, and the physicians are telling me twins are always smaller.”

I could barely stifle a shout. “By the gods, Aileen, you nearly bled to death! What do the physicians say to that?”

It wiped the forced gaiety from her face. “D’ye think I don’t know?” she cried. “D’ye think I rejoiced when they told me?” Such white, white flesh set in the frame of brilliant red hair; such green, frightened eyes, now dilated black. “’Twas all I could do not to vomit from the fear…not to disgrace myself before them, even as I saw the looks in their eyes. They are afraid, too…but heirs are worth the risk, and Aidan is oversmall and sickly. There’s a need for other sons.” Fingers clutched the folds of her skirts. “Gods, Keely, what am I to do?”

“Lose it,” I said succinctly. Then, more clearly, “Lose them.”

Aileen nearly gaped. Then closed her mouth and wet her lips with a tongue that shook a little. “Lose them,” she echoed.

“There are herbs,” I said impatiently. “Herbs to make you miscarry.”

Aileen’s voice sounded drugged. “You want me to kill my bairns?”

“Better them than you.” Sweat was drying on my face, against my scalp, beneath the leathers I wore: leggings baggy at the knees; sleeveless Cheysuli jerkin, belted snug; quilted, longsleeved undertunic, cuffs knotted at my wrists. I needed a bath badly, but this was more important. “Brennan has an heir. He needs a queen as well.”

“Oh, Keely.” With effort, she shook her head. “Oh—Keely—no. No. Kill my bairns? How could I? How could you even suggest it?”

“Easily,” I told her. “If it is a choice between losing you or keeping you, I would sooner lose the babies.”

“If you were a mother—”

I turned my hands palm-up. “But I am not. And, given the choice, I never will be.”

Aileen sat down again, hastily. “Why not?” she asked in shock. “How can ye not want bairns?”

I peeled sticky hair away from my face and smoothed it back, tucking it into my loosened braid. Not wanting to offend her with my odor—and unable to sit close while discussing something so personal—I eased myself down on the stone floor and leaned against the wall. The room was plain, unadorned, nothing more than what it was intended to be: a practice chamber for war.

“Babies require things,” I said. “Things such as constant responsibility…they steal time and freedom, robbing you of choice. They are parasites of the soul.”

“Keely!”

I sighed, knowing how callous it sounded; knowing also I meant it. “All my life I have fought for my freedom. I fight for it every day. And I will lose what I have won the moment I conceive.”

“’Tisn’t true!” she cried. “Have I lost my freedom?”

“Have you?” I countered. “Before you left Erinn and came here to Homana—before you fell in love with Corin—before you married Brennan…what was your life like?”

Aileen said nothing at all, because to speak was to lose the battle.

“On the day you lay down with Brennan, Aidan was conceived,” I said. “And from that day you became more than a woman, more than you: you became the vessel that housed Homana, because one day that child would be Mujhar. Your value was based solely on that, not on you, not on Aileen…but on that child—that bairn, as you would say—because babies born into royal houses are more than merely babies.” I shrugged. “They are coin to barter with, just as you and I were before we were even born.” I pulled my braid over one shoulder and played absently with the ends below the thong. It needed washing, like the rest of me. “I have no affection for babies; I would sooner do without.”

“You’ll not be saying that once you’re wed to Sean.”

She sounded so certain. So certain, in fact, it fanned unacknowledged resentment into too-hasty speech. “And how does it feel, Aileen, to lie in one man’s bed—to bear that man his children—while loving yet another?”

Aileen jumped to her feet. “Ye skilfin!” she cried. “Will ye throw that in my face? Will ye speak to me of things ye cannot understand, being but half a woman—” And abruptly, on a strangled cry of shock, she clamped her hands over her mouth. “Oh, Keely…oh, Keely, I swear…I swear—”

“—you did not mean it?” Emptily, I shrugged. “I have heard it said before. To me and about me.” I pressed myself up from the floor, brushing off the seat of my training leathers. “If I am considered half a woman simply because I prefer to be myself, not an appendage of a man—nor a mother to his children—then so be it. I am Keely…and that is all that counts.”

Some of the color had died out of her face. She was pale again, too pale. “Will you be saying all this to Sean?”

“As I have said it to you, I will say it to your brother.” I crossed the chamber to the door, which Griffon had pointedly closed. “I am not a liar, Aileen, nor one who admires deception. I was never asked if I wanted to marry, but was betrothed before my birth…I was never asked if, being a woman, I wanted to bear children. It was simply assumed…and that, my lady princess, is what I hate most of all.” I paused, my hand on the latch, and turned to face her fully. “But you would know.” I spoke more quietly now; it was not Aileen with whom I was angry. “You should know, being made to wed the oldest of Niall’s sons when you would sooner have the youngest. You would know how it feels to have things arranged for you, simply because of your gender.”

Straight red brows were lowered over an equally straight nose. She is not a beauty, Aileen, but anyone with half a mind sees past that to her fire. “I am not a slave,” she said darkly, “and neither am I a fool. There are things in life we’re made to do through no fault of our own, but because of necessity, regardless of gender…and that you should know, being a Cheysuli.” She paused, assessing me; I wondered, as I so often did, if the brother was anything like the sister. “Or are you Homanan today? Ah, no—perhaps Atvian, instead.” Aileen stood straight and tall before me, her pride a tangible thing. “It strikes me, my lady princess, that you are whatever you want to be whenever it takes your fancy. Whenever ’tis convenient.”

She meant it, I think, to sting. Instead, it made me laugh. “Aye,” I agreed, “whatever I want to be. Woman, warrior, animal…and I thank the gods for that magic.”

“Magic,” Aileen repeated. “Aye, I was forgetting that—but so, I’m thinking, are you. Because with the magic that makes you a shapechanger comes the price you’ll be having to pay. And someday, you’ll be paying it. Your tahlmorra will see to that.”

I frowned. “What price?”

“Marriage,” she said succinctly. “Marriage and motherhood; how else to forge the link the prophecy requires?”

I grinned at her. “Ah, but you have done that; you and my oldest rujholli. Aidan is the one. Aidan is the link. Aidan will be Mujhar.”

Evenly, she said, “Aidan may die by nightfall.”

It stopped me cold, as she meant it to. “Aileen—”

Her tone lacked expression. Like me, she masks herself rather than show her concern for things of great importance. “He is not well, Keely. Aidan has never been well, ever since the birth. He may die tonight. He may die next year.” She clasped her hands over her belly, swelling gently beneath her skirts. “And so you see, it becomes imperative that I bear Brennan another son.” She paused, holding me quite still with the power of her eyes and the knowledge of her duty, of her value, by which men too often judge women, especially those they marry. “Two would be even better, I’m thinking, in case they are sickly also.”

I thought of Aileen in potentially deadly labor, bringing forth two babies at once, for the sake of her husband’s throne. I recalled it from before, with Aidan’s birth; how she had bled and bled and nearly died, recovering so very slowly. And now she faced it again, but this time the threat was compounded.

Fear lurched out of my belly and found its way to my mouth. “Aileen, you could die.”

Her fingers tightened rigidly, clasping the unborn souls. “Men go to war. Women bear the bairns.”

I unlatched the door and shoved it open. But I did not leave at once. “Do you know,” I told her, “if I could, I would trade.”

“Would you?” Aileen asked. “Could you, do you think?”

I paused on the threshold, one shoulder against the wood. “If you are asking me if I could kill a man, then I say aye.”

Her face spasmed briefly. “So glib,” she said. “I’m thinking too glib; that you’re not knowing what you can—or cannot—do, and it irritates you. It frightens you—”

I overrode her crisply. “I will do what I must do.”

Slowly, Aileen smiled. And then she began to laugh as tears welled into her eyes. “So fierce,” she said, “so proud…and so very, very helpless. No less so than I.”

Denial, I thought, was futile; I closed the door on her noise.

Two

I itched. I wanted nothing more, at that moment, than to climb into a polished half-cask of steaming water, to soak away dried sweat, stretched muscles, irritation. But even as I gave the order for the bath and went into my chambers, untying the knots of my sweat-soiled undertunic, I was prevented. Because my father came in behind me, silently and without warning, and shut the heavy door.

“So,” he said, “you have been learning the sword from Griffon.”

For a moment, only a moment, I seriously considered stripping out of my boots and clothing anyway, just to see his reaction. I decided against it because, by the look in his eye, he would not be put off by anything, not even his daughter’s nudity, until he had his say.

My hands went to my hips. “Aye,” I agreed, saying nothing of Griffon’s defection; he was, after all, my father’s man, not mine. “I have made no secret of it.”

“But neither did you tell me.”

I thought it obvious, but said it anyway. “I knew you would tell me to stop.”

“And so you should.” He folded arms across his chest. “And so I do: stop.”

I pressed fingers against my breastbone, tapping for emphasis. “I am not a fragile, useless female…I know how to fight. All my rujholli have taught me knife and bow…why should I not learn the sword?”

He leaned against the door, assuming an attitude of relaxed, quiet authority; he could order me, I knew, and probably would, but if I could give him a logical argument beyond refute, I might yet win. Sometimes I could. Not often. Not nearly often enough.

I looked at my father’s face, seeing what others saw: lines of care and concern bracketing eyes and mouth; the silvering of his hair, mingled still with tawny brown; the leather patch stretched over the emptiness that once had been his right eye.

But I saw more than that. I saw kindness and compassion. Strength of spirit and will. Loyalty and love, honesty and pride, and a tremendous dedication to his personal convictions.

Still, I could not give in so easily. He had taught me that.

He countered my question with one of his own. “Why do you want to learn the sword?”

I shrugged. “I do. I want to know them all, all the weapons men use in war…not because I desire to go to war, but because I have an interest in weapons.” Balancing storklike on one leg, I twisted my knee up and tugged on the toe and heel of my left boot to work if off. “Why do you ask me such things, jehan? You never ask Deirdre why she weaves that tapestry of lions…nor Brennan why he enjoys training and racing his horses. You only ask me, because I care for things you and other men think unseemly to a woman.” The boot came off; I dropped it and traded feet, feeling the chill of stone on my now-bare sole. “You are such a stalwart champion of fairness and justice, jehan—and yet you are blind to unfairness and injustice under your own roof.”

“I hardly think it is unfair to ask my daughter to cease learning the sword,” he said flatly. “By the gods, Keely, you have known more freedom than any woman born in the last fifty or sixty years…you have the gift of lir-shape, and you speak freely to all the lir. All that, and yet you also insist on tricking my arms-master into teaching you the sword.”

I dropped the other boot to the floor, hearing the heel smack sharply against rose-red stone. “It was no trick,” I retorted, stung. “Hart taught me how to wager…I won Griffon’s service from him fairly.”

He sighed and rubbed wearily at his brow, automatically resettling the leather strap that held the eyepatch in place. “Hart taught you how to wager, Corin how to rebel…it would be too much to assume Brennan taught you civility and respect—”

I cut him off even as I moved to stand on a rug. “Do you want to know what Brennan has taught me, jehan? He has taught me that a man has no regard for his cheysula, thinking only of himself…by the gods, jehan, Aidan’s birth nearly killed Aileen! And now she must go through it again, with two?” I shook my head. “Teach Brennan restraint, jehan, and then perhaps I will allow him to teach me civility and respect.”

Weary good humor dissolved. “That is between Brennan and Aileen, Keely. Your feelings are well known on the subject; I think we will get no objectivity from you.”

I yanked the knotted thong out of my braid and began unthreading plaited hair violently. “Oh, and I suppose you think making me put down the sword will transform me into an obedient, compliant woman. One like your beloved Maeve, perhaps, giving in to Teirnan when she knows betterR

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...