- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

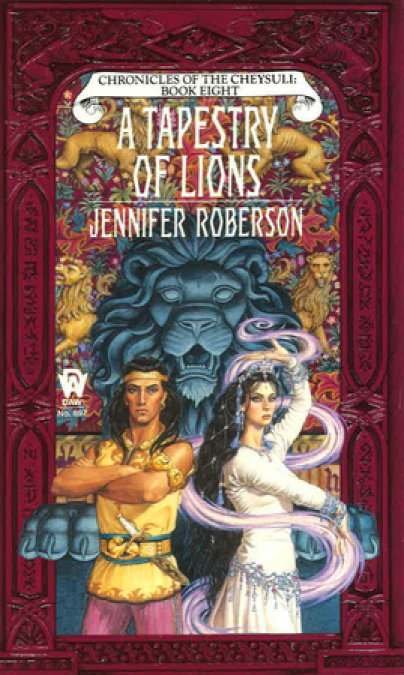

The final book in the Chronicles of the Cheysuli concludes the tale of magical warriors and shapeshifters as they battle the sorcerers that threaten their existence

Nearly a century has passed since the Prophecy of the Firstborn was set in motion—the generational quest to recreate the magical race which once held sway in the lands ruled by Homana's Mujar. Now, Kellin, heir to Homana's throne, has only to sire an offspring with an Ihlini woman to reach this goal. But Kellin wants nothing of prophecy, nor even of his own magical heritage. Embittered by tragedy, he refuses the sacred lir-bonding, becoming anathema in the eyes of his Cheysuli kin.

But willing participant or not, Kellin provides a very real threat to the Ihlini—the ancient enemies of the Cheysuli people—for should the prophecy be fulfilled, life as the Ihlini know it will end. How can a lirless warrior ever hope to escape the traps of the Ihlini sorcerers? And how can the prophecy ever be realized when the man born to become its final champion shuns his destined role?

Release date: December 1, 1992

Publisher: DAW

Print pages: 544

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Tapestry of Lions

Jennifer Roberson

THE FORTUNE-TELLER…

reached out and caught at his hands, trapped the fingers in his own, and Kellin’s speech was banished.

This time there were no gods to invoke. The words spilled free of the stranger’s mouth as if he could not stop them. “He is the sword,” the hissing voice whispered. “The sword and the bow and the knife. He is the weapon of every man who uses him for ill, and the strength of every man who uses him for good. Child of darkness, child of light; of like breeding with like, until the blood is one again. He is Cynric: the sword and the bow and the knife, and all men shall name him evil until Man is made whole again.”

The voice stopped. Kellin stared, struggling to make an answer, any sort of answer, but the sound began again.

“The lion shall lie down with the witch; out of darkness shall come light; out of death: life; out of the old: the new. The lion shall lie down with the witch, and the witch-child born to rule what the lion must swallow. The lion shall devour the House of Homana and all of her children, so the newborn child shall sit upon the throne and know himself lord of all.”

A shudder wracked Kellin from head to toe, and then he cried out and snatched his hands away.

He scrambled to his feet even as the guardsmen shredded canvas with steel to enter the tent. He saw their faces, saw their intent. One of the guards put his hand upon his prince’s rigid shoulder, but Kellin did not feel it.

The Lion. The LION.

None of them understood. No one at all knew him for what he was. They saw only the boy…

But the Lion wanted him.

Don’t miss JENNIFER ROBERSON’S monumental fantasies:

CHRONICLES OF THE CHEYSULI:

SHAPECHANGERS

THE SONG OF HOMANA

LEGACY OF THE SWORD

TRACK OF THE WHITE WOLF

A PRIDE OF PRINCES

DAUGHTER OF THE LION

FLIGHT OF THE RAVEN

A TAPESTRY OF LIONS

THE NOVELS OF TIGER AND DEL:

SWORD-DANCER

SWORD-SINGER

SWORD-MAKER

SWORD-BREAKER

SWORD-SWORN

SWORD-BORN

SWORD-BOUND

KARAVANS:

KARAVANS

DEEPWOOD

THE WILD ROAD

CHRONICLES

OF THE CHEYSULI:

BOOK EIGHT

A TAPESTRY

OF LIONS

JENNIFER ROBERSON

The Chronicles of the Cheysuli:

An Overview

THE PROPHECY OF THE FIRSTBORN:

“One day a man of all blood shall unite, in peace,

four warring realms and two magical races.”

Originally a race of shapechangers known as the Cheysuli, descendants of the Firstborn, Homana’s original race, held the Lion Throne, but increasing unrest on the part of the Homanans, who lacked magical powers and therefore feared the Cheysuli, threatened to tear the realm apart. The Cheysuli royal dynast voluntarily gave up the Lion Throne so that Homanans could rule Homana, thereby avoiding fullblown internecine war.

The clans withdrew altogether from Homanan society save for one remaining and binding tradition: each Homanan king, called a Mujhar, must have a Cheysuli liege man as bodyguard, councillor, companion, dedicated to serving the throne and protecting the Mujhar, until such a time as the prophecy is fulfilled and the Firstborn rule again.

This tradition was adhered to without incident for nearly four centuries, until Lindir, the only daughter of Shaine the Mujhar, jilted her prospective bridegroom to elope with Hale, her father’s Cheysuli liege man. Because the jilted bridegroom was the heir of a neighboring king, Bellam of Solinde, and because the marriage was meant to seal an alliance after years of bloody war, the elopement resulted in tragic consequences. Shaine concocted a web of lies to salve his obsessive pride, and in so doing laid the groundwork for the annihilation of a race.

Declared sorcerers and demons dedicated to the downfall of the Homanan throne, the Cheysuli were summarily outlawed and sentenced to immediate execution if found within Homanan borders.

Shapechangers begins the “Chronicles of the Cheysuli,” telling the tale of Alix, daughter of Lindir, once Princess of Homana, and Hale, once Cheysuli liege man to Shaine. Alix is an unknown catalyst bearing the Old Blood of the Firstborn, which gives her the ability to link with all lir and assume any animal shape at will. But Alix is raised by a Homanan and has no knowledge of her abilities, until she is kidnapped by Finn, a Cheysuli warrior who is Hale’s son by his Cheysuli wife, and therefore Alix’s half-brother. Kidnapped with her is Carillon, Prince of Homana. Alix learns the true power in her gifts, the nature of the prophecy which rules all Cheysuli, and eventually marries a warrior, Duncan, to whom she bears a son, Donal, and, much later, a daughter, Bronwyn. But Homana’s internal strife weakens her defenses. Bellam of Solinde, with his sorcerous aide, Tynstar the Ihlini, conquers Homana and assumes the Lion Throne.

In The Song of Homana, Carillon returns from a five-year exile, faced with the difficult task of gathering an army capable of overcoming Bellam. He is accompanied by Finn, who has assumed the traditional role of liege man. Aided by Cheysuli magic and his own brand of personal power, Carillon is able to win back his realm and restore the Cheysuli to their homeland by ending the purge begun by his uncle, Shaine, Alix’s grandfather. He marries Bellam’s daughter to seal peace between the lands, but Electra has already cast her lot with Tynstar the Ihlini, and works against her Homanan husband. Carillon’s failure to father a son forces him to betroth his only daughter, Aislinn, to Donal, Alix’s son, whom he names Prince of Homana. This public approbation of a Cheysuli warrior is the first step in restoring the Lion Throne to the sovereignty of the Cheysuli, required by the prophecy, and sows the seeds of civil unrest.

Legacy of the Sword focuses on Donal’s slow assumption of power within Homana, and his personal assumption of his role in the prophecy. Because by clan custom a warrior is free to take both wife and mistress, Donal has started a Cheysuli family even though he will one day have to marry Carillon’s daughter to cement his right to the Lion Throne. By his Cheysuli mistress he has two children, Ian and Isolde; by Aislinn, Carillon’s daughter, he eventually sires a son who will become his heir. But the marriage is rocky immediately; in addition to the problems caused by a second family, Donal’s Homanan wife is also under the magical influence of her mother, Electra, who is mistress to Tynstar. Problems are compounded by the son of Tynstar and Electra, Strahan, who has his father’s powers in full measure. On Carillon’s death Donal inherits the Lion, naming his legitimate son, Niall, to succeed him. But to further the prophecy he marries his sister, Bronwyn, to Alaric of Atvia, lord of an island kingdom. Bronwyn is later killed by Alaric accidentally while in lir-shape, but lives long enough to give birth to a daughter, Gisella, who is mad.

In Track of the White Wolf, Donal’s son Niall is a young man caught between two worlds. To the Homanans, fearful of Cheysuli power and intentions, he is worthy only of distrust, the focus of their discontent. To the Cheysuli he is an “unblessed” man, because even though far past the age for it, Niall has not linked with his animal. He is therefore a lirless man, a warrior with no power, and such a man has no place within the clans. His Cheysuli half-brother is his liege man, fully “blessed,” and Ian’s abilities serve to add to Niall’s feelings of inferiority.

Niall is meant to marry his half-Atvian cousin, Gisella, but falls in love with the princess of a neighboring kingdom, Deirdre of Erinn. Lirless, and with Gisella under the influence of Tynstar’s Ihlini daughter, Lillith, Niall falls prey to sorcery. Eventually he links with his lir and assumes the full range of Cheysuli powers, but he pays for it with an eye. His marriage to Gisella is disastrous, but two sets of twins are born—Brennan and Hart, Corin and Keely—which gives Niall the opportunity to extend his range of influence via betrothal alliances. He banishes Gisella to Atvia after he foils an Ihlini plot involving her, and then settles into life with his mistress, Deirdre of Erinn, who has already borne Maeve, his illegitimate daughter.

A Pride of Princes tells the story of each of Niall’s three sons. Brennan, the eldest, will inherit Homana and has been betrothed to Aileen, Deirdre’s niece, to add a heretofore unknown bloodline to the prophecy. Brennan’s twin, Hart, is Prince of Solinde, a compulsive gambler whose addiction results in a tragic accident involving all three of Niall’s sons. Hart is banished to Solinde for a year, and the rebellious youngest son, Corin, to Atvia. Brennan is tricked into siring a child on an Ihlini-Cheysuli woman; Hart loses a hand and nearly his life in a Solindish plot; in Erinn, Corin falls in love with Brennan’s bride, Aileen, before going to Atvia. One by one each is captured by Strahan, Tynstar’s son, who intends to turn Niall’s sons into puppet-kings so he can rule through them. All three manage to escape, but not until after each has been made to recognize particular strengths and weaknesses.

For Keely, sister of Niall’s sons, things are different. In Daughter of the Lion, Keely herself is caught up in the machinations of politics, evil sorcery, and her own volatile emotions. Trained from childhood in masculine pursuits such as weaponry, Keely prefers the freedom of choice and lifestyle, and as both are threatened by the imminent arrival of her betrothed, Sean of Erinn, she fights to maintain her sense of self in a world ruled by men. She is therefore ripe for rebellion when a strong-minded, powerful Erinnish brigand—and possible murderer—enters her life.

But Keely’s battles are increased tenfold when Strahan chooses her as his next target. Betrayed, trapped, and imprisoned on the Crystal Isle, Keely is forced through sorcery into a liaison with the Ihlini that results in pregnancy. But before the child can be born, Keely escapes with the aid of the Ihlini bard, Taliesin. On her way home she meets the man believed to be her betrothed, and realizes not only must she somehow rid herself of the unwanted child, but must also decide which man she will have—thief or prince—in order to be a true Cheysuli in service to the prophecy.

Flight of the Raven is the story of Aidan, only son of Brennan and Aileen. Hounded in childhood by nightmares, Aidan grows to adulthood convinced he is not meant to hold the Lion Throne after all, but is intended to follow a different path. This path becomes more evident as he sets out to visit his kin in Solinde and Erinn in order to find a bride; very quickly it becomes apparent that Aidan has been singled out by the Cheysuli gods to complete a quest for golden links personifying specific Mujhars. In pursuing his quest, Aidan becomes the target of Lochiel the Ihlini, Strahan’s son.

Bound by their mutual Erinnish gift of kivarna, a strong empathy, Aidan and Shona of Erinn marry. The child of this union will bring the Cheysuli one step closer to completion of the prophecy, and is therefore a grave threat to Lochiel. The Ihlini attacks Clankeep, kills Shona, and cuts the child from her belly. Aidan, seriously wounded, falls victim to epilepsy; in his “fits” he prophesies of the coming of Cynric, the Firstborn. To get back his stolen child, Aidan conquers his weakness to confront Lochiel in Valgaard itself, where he wins back his son. But Aidan realizes he is not meant for thrones and titles; he renounces his rank, gives his son, Kellin, into the keeping of Aileen and Brennan, and takes up residence as a shar tahl on the Crystal Isle, where he begins to prepare the way for the coming of the Firstborn.

Table of Contents

Prologue

In thread, on cloth, against a rose-red stone wall gilt-washed by early light: Lions. Mujhars, Cheysuli, and Homanan; and the makings of the world in which the boy and his grand-uncle lived.

“Magic,” the boy declared solemnly, more intent upon his declaration than most eight-year-olds; but then most eight-year-old boys do not discover magic within the walls of their homes.

The old man agreed easily without the hesitation of those who doubted, or wished to doubt, put off by magic’s power; magic was no more alien to him than to the boy, in whose blood it lived as it lived in his own, and in others Cheysuli-born.

“Woman’s magic,” he said, “conjured from head and hands.” His own long-fingered left hand, once darkly supple and eloquent, now stiffened bone beneath wrinkled, yellowing flesh, traced out the intricate stitchwork patterns of the massive embroidered arras hung behind the Lion Throne. “Do you see, Kellin? This is Shaine, whom the Homanans would call your five times great-grandfather. Cheysuli would call him hosa’ana.”

It was mid-morning in Shaine’s own Great Hall. Moted light sliced through stained glass casements to paint the hall all colors, illuminating the vast expanse of ancient architecture that had housed a hundred kings long before Kellin—or Ian—was born.

The boy, undaunted by the immensity of history or the richness of the hammer-beamed hall and its multitude of trappings, nodded crisply, a little impatient, black brows drawn together in a frown old for his years; as if Kellin, Prince of Homana, knew very well who Shaine was, but did not count him important.

Ian smiled. And well he might not; his history is more recent, and his youth concerned with now, not yesterday’s old Mujhars.

“Who is this?” A finger, too slender for the characteristic incomplete stubbiness of youth—Cheysuli hands, despite the other houses thickening his blood—transfixed a stitchwork lion made static by the precise skill of a woman’s hands. “Is this my father?”

“No.” The old man’s lean, creased-leather face gave away nothing of his thoughts, nothing of his feelings, as he answered the poorly concealed hope in the boy’s tone. “No, Kellin. This tapestry was completed before your father was born. It stops here—you see?—” he touched thread, “—with your grandsire.”

A dirt-rimmed fingernail bitten off crookedly inserted itself imperatively between dusty threads, once-brilliant colors muted by time and long-set sunlight. “But he should be here. My father. Somewhere.”

The expression was abruptly fierce, no longer hopeful, no longer clay as yet unworked, but the taut arrogance of a young warrior as he looked up at the old man, who knew more than the boy what it was to be a warrior; he had even been in true war, and was not merely a construct of aging tales.

Ian smiled, new wrinkles replacing old between the thick curtains of snowy hair. “And so he would be, had it taken longer for Deirdre and her women to complete the Tapestry of Lions. Perhaps someday another woman will begin a new tapestry and put you and your father and your heir in it.”

“Mujhars,” Kellin said consideringly. “That’s what all of them were.” He glanced back at the huge tapestry filling the wall behind the dais, fixing a dispassionate gaze upon it. The murmured names were a litany as he moved his finger from one lion to another: “Shaine, Carillon, Donal, Niall, Brennan…” Abruptly the boy broke off and took his finger from the stitching. “But my father isn’t Mujhar and never will be.” He stared hard at the old man as if he longed to challenge but did not know how. “Never will be.”

It did not discomfit Ian, who had heard it phrased one way or another for several years. The intent was identical despite differences in phraseology: Kellin desperately wanted his father, Aidan, whom he had never met. “No,” Ian agreed. “You are next, after Brennan…they have told you why.”

The boy nodded. “Because he left.” He meant to sound matter-of-fact, but did not; the unexpected shine of tears in clear green eyes dissipated former fierceness. “He ran away!”

Ian tensed. It would come, one day; now I must drive it back. “No.” He reached and caught one slight shoulder, squeezing slightly as he felt the suppressed, minute trembling. “Kellin—who said such a monstrous thing? It is not true, as you well know…your father ran from nothing, but to his tahlmorra—”

“They said—” Kellin’s lips were white as he compressed them. “They said he left because he hated me.”

“Who said this?”

Kellin bit into his bottom lip. “They said I wasn’t the son he wanted.”

“Kellin—”

It was very nearly a wail though he worked to choke it off. “What did I do to make him hate me so?”

“Your jehan does not hate you.”

“Then why isn’t he here? Why can’t he come? Why can’t I go there?” Green eyes burned fiercely. “Have I done something wrong?”

“No. No, Kellin—you have done nothing wrong.”

The small face was pale. “Sometimes I think I must be a bad son.”

“In no way, Kellin—”

“Then, why?” he asked desperately. “Why can’t he come?”

Why indeed? Ian asked himself. He did not in the least blame the boy for voicing what all of them wondered, but Aidan was intransigent. The boy was not to come until he was summoned. Nor would Aidan visit unless the gods indicated it was the proper time. But will it ever be the proper time?

He looked at the boy, who tried so hard to give away none of his anguish, to hide the blazing pain. Homana-Mujhar begins to put jesses on the fledgling.

Strength waned. Ian desired to sit down upon the dais so as to be on the boy’s level and discuss things more equally, but he was old, stiff, and weary; rising again would prove difficult. There was so much he wanted to say that little of it suggested a way to be said. Instead, he settled for a simple wisdom. “I think perhaps you have spent too much time of late with the castle boys. You should ask to go to Clankeep. The boys there know better.”

It was not enough. It was no answer at all. Ian regretted it immediately when he saw Kellin’s expression.

“Grandsire says I may not go. I am to stay here, he says—but he won’t tell me why. But I heard—I heard one of the servants say—” He broke it off.

“What?” Ian asked gently. “What have the servants said?”

“That—that even in Clankeep, the Mujhar fears for my safety. That because Lochiel went there once, he might again—and if he knew I was there…” Kellin shrugged small shoulders. “I’m to be kept here.”

It is no wonder, then, he listens to castle boys. Ian sighed and attempted a smile. “There will always be boys who seek to hurt with words. You are a prince—they are not. It is resentment, Kellin. You must not put faith in what they say about your jehan. They none of them know what he is.”

Kellin’s tone was flat, utterly lifeless; his attempt to hide the hurt merely increased its poignancy. “They say he was a coward. And sick. And given to fits.”

All this, and more…he has years yet before they stop, if any of them ever will stop; it may become a weapon meant to prick and goad first prince, then Mujhar. Ian felt a tightness in his chest. The winter had been cold, the coldest he recalled in several seasons, and hard on him. He had caught a cough, and it had not completely faded even with the onset of full-blown spring.

He drew in a carefully measured breath, seeking to lay waste to words meant to taunt the smallest of boys who would one day be the largest, in rank if not in height. “He is a shar tahl, Kellin, not a madman. Those who say so are ignorant, with no respect for Cheysuli customs.” Inwardly he chided himself for speaking so baldly of Homanans to a young, impressionable boy, but Ian saw no reason to lie. Ignorance was ignorance regardless of its racial origins; he knew his share of stubborn Cheysuli, too. “We have explained many times why he went to the Crystal Isle.”

“Can’t he come to visit? That’s all I want. Just a visit.” The chin that promised adult intransigence was no less tolerant now. “Or can’t I go there? Wouldn’t I be safe there, with him?”

Ian coughed, pressing determinedly against the sunken breastbone hidden beneath Cheysuli jerkin as if to squeeze his lungs into compliance. “A shar tahl is not like everyone else, Kellin. He serves the gods…he cannot be expected to conduct himself according to the whims and desires of others.” It was the simple truth, Ian knew, but doubted it offered enough weight to crush a boy’s pain. “He answers to neither Mujhar nor clan-leader, but to the gods themselves. If you are to see your jehan, he will send for you.”

“It isn’t fair,” Kellin blurted in newborn bitterness. “Everyone else has a father!”

“Everyone else does not have a father.” Ian knew of several boys in Homana-Mujhar and Clankeep who lacked one or both parents. “Jehans and jehanas die, leaving children behind.”

“My mother died.” His face spasmed briefly. “They said I killed her.”

“No—” No, Kellin had not killed Shona; Lochiel had. But the boy no longer listened.

“She’s dead—but my father is alive! Can’t he come?”

The cough broke free of Ian’s wishes, wracking lungs and throat. He wanted very much to answer the boy, his long-dead brother’s great-grandson, but he lacked the breath for it. “—Kellin—”

At last the boy was alarmed. “Su’fali?” Ian was many generations beyond uncle, but it was the Cheysuli term used in place of a more complex one involving multiple generations. “Are you sick still?”

“Winter lingers.” He grinned briefly. “The bite of the Lion…”

“The Lion is biting you?” Kellin’s eyes were enormous; clearly he believed there was truth in the imagery.

“No.” Ian bent, trying to keep the pain from the boy. It felt as if a burning brand had been thrust deep into his chest. “Here—help me to sit…”

“Not there, not on the Lion—” Kellin grasped a trembling arm. “I won’t let him bite you, su’fali.”

The breath of laughter wisped into wheezing. “Kellin—”

But the boy chattered on of a Cheysuli warrior’s protection, far superior to that offered by others unblessed by lir or shapechanging arts and the earth magic, and guided Ian down toward the step. The throne’s cushion would soften the harshness of old wood, but clearly the brief mention of the Lion had burned itself into Kellin’s brain; the boy would not allow him to sit in the throne now, even now, and Ian had no strength to dissuade him of his false conviction.

“Here, su’fali.” The small, piquant face was a warrior’s again, fierce and determined. The boy cast a sharp glance over his shoulder, as if to ward away the beast.

“Kellin—” But it hurt very badly to talk through the pain in his chest. His left arm felt tired and weak. Breathing was difficult. Lir…It was imperative, instinctive; through the lir-link Ian summoned Tasha from his chambers, where she lazed in a shaft of spring sunlight across the middlemost part of his bed. Forgive my waking you—

But the mountain cat was quite awake and moving, answering what she sensed more clearly than what she heard.

And more— With the boy’s help Ian lowered himself to the top step of the dais, then bit back a grimace. Breathlessly, he said, “Kellin—fetch your grandsire.”

The boy was all Cheysuli save for lighter-hued flesh and Erinnish eyes, wide-sprung eyes: dead Deirdre’s eyes, who had begun the tapestry for her husband, Niall, Ian’s half-brother, decades before …—green as Aileen’s eyes—…the Queen of Homana, grandmother to the boy; sister to Sean of Erinn, married to Keely, mother of Kellin’s dead mother. So many bloodlines now…have we pleased the gods and the prophecy?

The flesh of Kellin’s Cheysuli face was pinched Homanan-pale beneath thick black hair. “Su’fali—”

Ian twitched a trembling finger in the direction of the massive silver doors gleaming dully at the far end of the Great Hall. “Do me this service, Kellin—”

And as the boy hastened away, crying out loudly of deadly lions, the dying Cheysuli warrior bid his mountain cat to run.

PART I

One

“Summerfair,” Kellin whispered in his bedchamber, testing the sound of the word and all its implications. Then, in exultation, “Summerfair!”

He threw back the lid of a clothing trunk and fetched out an array of velvets and brocades, tossing all aside in favor of quieter leathers. He desired to present himself properly but without Homanan pretension, which he disliked, putting into its place the dignity of a Cheysuli.

Summerfair. He was to go, this year. Last year it had been forbidden, punishment as much for his stubborn insistence that he had been right as for the transgression itself, which he still believed necessary. They had misunderstood, his grandsire and granddame, and all the castle servants; they had all misunderstood, each and every one, regardless of rank, birth, or race.

Ian would have understood, but Kellin’s harani was two years’ dead. And it was because of Ian’s death—and the means by which that death was delivered—that Kellin sought to destroy what he viewed as further threat to those he loved.

None of them understood. But his mind jumped ahead rapidly, discarding the painful memories of that unfortunate time as he dragged forth from the trunk a proper set of Cheysuli leathers: soft-tanned, russet jerkin with matching leggings; a belt fastened with onyx and worked gold; soft, droopy boots with soles made for leaf-carpeted forest, not the hard bricks of the city.

“—still fit—?” Kellin dragged on one boot and discovered that no, it did not fit, which meant the other didn’t either; which meant he had grown again and was likely in need of attention from Aileen’s sempstresses with regard to Homanan clothing…He grimaced. He intensely disliked such attention. Perhaps he could put on the Cheysuli leathers and wear new Homanan boots; or was that sacrilege?

He stripped free of Homanan tunic and breeches and replaced them with preferred Cheysuli garb, discovering the leggings had shrunk; no, his legs had lengthened, which Kellin found pleasing. For a time he had been small, but it seemed he was at last making up for it. Perhaps now no one would believe him a mere eight-year-old, but would understand the increased maturity ten years brought.

Kellin sorted out the fit of his clothing and clasped the belt around slender hips, then turned to survey himself critically in the polished bronze plate hung upon the wall. Newly-washed hair was drying into accustomed curls—Kellin, frowning, instantly tried to mash them away—but his chin was smooth and childish, unmarred by the disfiguring hair Homanans called a beard. Such a thing marked a man less than Cheysuli, Kellin felt, for Cheysuli could not ordinarily grow beards—although some mixed-blood Cheysuli not only could but did; it was said Corin, in distant Atvia, wore a beard, as did Kellin’s own Erinnish grandfather, Sean—but he would never do so. Kellin would never subscribe to a fashion that hid a man’s heritage behind the hair on his face.

Kellin examined his hairless chin, then ran a finger up one soft-fleshed cheek, across to his nose, and explored the curve of immature browbone above his eyes. Everyone said he was a true Cheysuli, save for his eyes—and skin tinted halfway between bronze and fair; though in sum

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...