- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

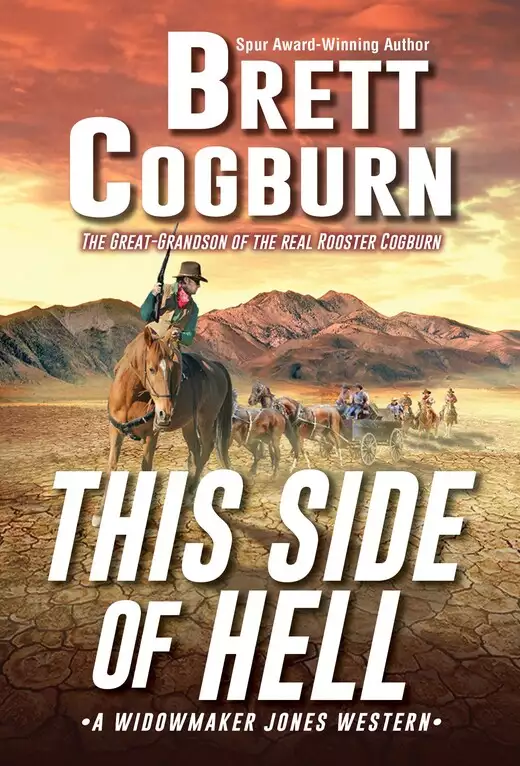

THE WIDOWMAKER MEETS POKER ALICE.The most famous lady gambler of the Old West teams up with the Widowmaker Jones in a doomed search for lost treasure, a deadly trek through the desert—and a dangerous alliance with the greatest gunslingers in history . . .IT'S A MATCH MADE IN HELL. Card player extraordinaire Poker Alice knows when hold 'em, when to fold 'em, and when to team up with master gunman Newt "Widowmaker" Jones. She's betting on Jones to protect her—and her money—on a treasure hunt in the California desert. Legend has it that a shipwreck is buried in the Salton sands. Some say it's a Spanish galleon that got stuck when the sea ran dry. Other says it's a Chinese junk full of pearls or a Viking ship filled with Aztec treasure. Either way, a lot of very mean and dangerously violent folks would kill to find it. Which is why Poker Annie needs the Widowmaker. In this game, it's winner takes all. Losers die . . .Praise for Spur Award winner Brett Cogburn "Fans of frontier arcana will revel in Cogburn's readable prose and lively characters."—Publishers Weekly on Rooster "Cogburn amazes and astounds." —Booklist

Release date: February 23, 2021

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

This Side of Hell

Brett Cogburn

It was a burning land he stood upon, where shade was as scarce as water; where the rocks were scorched like cinders and left so lava-hot that they would sear bare flesh at a touch. It was no place for a man, especially for a man on foot without water, and with a ragged hole in his side.

He shifted his gaze back the way he had come, through the chain of rugged mountains and canyons leading up from the desert valley, and to the far side of that valley and the blow sand there. Those dunes were miles and miles behind him, but his memory of them was as clear as if he could see them now. Those shifting, blowing mounds continually reshaped themselves under the hot wind, one grain of sand at a time. The boot prints he had left in those dunes two days before were likely already gone, as if he had never existed in that place at all, a story told and untold. The distance between there and where he now stood was as good a place to die as any he had ever traveled, only he wasn’t dead, not yet.

Sixty miles or more he had come, a great deal of that on foot, one staggering step at a time, bleeding until the blood, too, dried up like the rest of him, and then up through the rocky, barren canyons, working himself westward. The hot ground blistered the soles of his feet through his thin boot soles and rocks cut him when he fell. And fall he did, more than once, and each time it took him longer to get back up. Nothing but rage and sheer stubbornness carried him on.

Water—he had thought about it for every one of those miles out of the dune sand and across the valley and suffered for want of it. The pain of the bullet wound in his side was child’s play compared to that thirst.

And yet, he kept going, the line of his travel straight and true, even though he knew not the hellish country through which he passed. It wasn’t any landmark or some distinctive feature of the treeless, rock-pile mountains to the west that guided him, but rather the occasional hoof print pressed into the earth ahead of him, or here and there where one of those same iron-shod hooves had scored a rock or crushed some brittle desert plant beneath its weight. He wasn’t an exceptional tracker, even less so in his current condition, but his bloodshot eyes locked on to the horse tracks, homing in on them like a man reaching for a rope to pull him out of a dark pit. He had become a manhunter, and not for the first time in his life.

He gave one last glance at the desiccated, mummified skeleton of the dead horse lying in the rocks at his feet, the same skeleton that he had jerked the jawbone from. It was hard to tell how long the horse had been dead, a single year or a hundred years. The desert was like that, burning the juices out of you until you were nothing but bits of leather and bone, and then preserving your pitiful remnants to the point that the ancient was new and the new was ancient, everything equally withered and dry.

There was an old, dry-rotted saddle and saddle blanket with the horse’s skeleton, and the Widowmaker put a boot against the saddle and gave a shove. The bones scattered and fell apart, and he could feel his own pieces falling away, creaking and popping and crumbling, no matter how hard he tried to keep himself together.

A rattlesnake under the saddle, its shade disturbed, slithered through the horse skeleton’s rib bones and then coiled and posed to strike. Its unblinking eyes stared at the man thing that had torn down its kingdom and its tail rattles buzzed as dry and brittle as death.

He ignored the rattlesnake and walked on, the jawbone in his fist swinging at his side. The hoof prints he had been following led up a canyon, so that was the way he went. The only sound in his head was the sound of his worn boot soles scraping and scuffing over the rough ground and the slow, dull throb of his heartbeat pounding in his head.

His stride was uneven and short, especially for a man of his height, but the only way to go left to him was slow. He was so tired that he couldn’t tell if the heat waves had grown worse ahead of him or if it was simply that his eyes refused to focus.

As it was, it was nearing sundown when the canyon made a sharp bend to the west around the foot of a rocky mountain point. He rounded that turn and saw a clump of palm trees against a bluff not a hundred yards higher up the canyon. Such trees in the desert likely marked an oasis of some kind, a spring, tank, or some source of water belowground. He blinked once, and then twice, to make sure he was seeing what he was seeing.

There was a trickle of smoke floating up from the campfire someone had built in that grove of palm trees. At the sight of the smoke he forgot about the water and he forgot about his wounds, and he gripped the jawbone in his right fist until the line of ivory teeth in it cut into his fingers.

They would be up there in those palms—seven guns or maybe more, the same men who had left him for dead out on the dunes. The jawbone scraped against the empty pistol holster on his right hip when he shifted his grip on it, and a drop of blood fell onto one of his boot toes from his bleeding hand.

He started toward the palm trees in the evening dusk, making no attempt at stealth, and something hotter than the desert furnace burning in his eyes. “Leave me for dead, will you? Well, I ain’t dead yet, but you’re going to wish to hell I was.”

Six days earlier, San Bernardino, California

Newt Jones woke with an aching back and a bad attitude. The aching back was a symptom of the sagging mattress on the jailhouse cot he had slept on, and the bad attitude was a result of the month he had spent locked up in a ten-by-ten cell. The morning sunlight shined through the single, barred window at the foot of his cot and struck him full in the face, worsening his mood and causing him to squint and scowl. He was always grouchy when he first got up.

He threw a forearm across his eyes to shield against the sunlight and groaned as he swung his legs off the cot and sat upright. It took him several minutes to decide whether it was worth all the trouble to get up and to come fully awake, but he finally managed to rake back his hair from his brow and settle a crumpled black hat on his head before he stood and went to the window.

Four men were crossing the street going dead away from him, their voices receding as they went. No matter how their voices faded, they were loud enough for Newt to surmise that it had been their conversation that had woken him. Undoubtedly, they had begun their talk under his window and were now moving elsewhere. He scowled again, rubbed a pointer finger absentmindedly along the crooked bridge of his nose, and watched them stop on the other side of the street. The one doing most of the talking had taken a stance on the raised boardwalk in front of Kerr’s Emporium, the town’s biggest general store, and the other men remained in front of the speaker on the edge of the street.

The man on the boardwalk was tall and thin and dressed in a white shirt, blue denim pants, and high-topped boots. Other than that, Newt couldn’t make out much more about him, for the tipped-down brim of the man’s hat hid most of his facial features. The distance was too great and the man was talking too quietly for Newt to make out the words, but from the his hand gestures and the way he had the group’s attention he was either quite the orator or had something really interesting to say.

The sound of a door opening behind Newt caused him to turn around to watch the city marshal come into the walkway between the row of cells down either side of it. Buck Tillerman was a tidy, stocky fellow with a short-brimmed gray hat as pale as the walrus mustache that draped over his upper lip. The marshal took hold of the Saint Christopher medallion watch fob dangling from the chain across the front of his vest and pulled out a pocket watch which he frowned over, moving the watch farther from his face and to arm’s length to properly focus on the time.

“Morning, Marshal,” Newt said as he came over to grip the bars of the door to his cell. “When I heard you I figured you were the jailer coming with my breakfast.”

“No sense in costing the taxpayers the price of another meal to feed you,” the marshal said.

“Well, let me out of here,” Newt said when the marshal made no move to open the cell.

Marshal Tillerman continued to monitor the watch face and never bothered to look up at Newt, much less reply to him.

“You’re actually counting off my time?” Newt asked.

“Thirty days Judge Kerr gave you, and thirty days is what you’ll serve. Not a minute less. Although I’m good and ready to get rid of you, I’ll tell you that,” the marshal said after he gave a short grunt. “I prefer my prisoners less on the surly side and more repentant.”

“This jail cell isn’t exactly good for morale and pleasant demeanor.”

“You remember that the next time you come to my town.” The marshal pocketed the watch and sorted through a ring of keys. “I told you to call off the fight, but still you and that gambling crowd had to try it anyway on the sneak.”

“No harm in a little friendly pugilism to pass the time.” Newt shrugged.

It was a reoccurring argument between them, almost daily, and one too late to win. Bringing it up again was nothing but sheer stubbornness, but Newt did it anyway. And rankling the marshal had become something of a sport for him to fight the melancholy and boredom, and a sort of minor revenge when he could have no other kind.

“I don’t make the laws. Tell that to the reformers in the governor’s office or the legislature if you’re of a mind to,” the marshal said.

“From what I hear, nobody’s enforced that prizefighting law out here since they passed it better’n thirty years ago.”

“It’s still the law, and the Judge is a real stickler for what’s right and proper.”

“Judge Kerr, I’d as soon never see him again. Once in front of his bench is enough. That old highbinder wouldn’t happen to be the owner of that store out yonder?” Newt jerked a thumb over his shoulder at the window looking out on the mercantile across the street.

“No, that belongs to his brother.” The marshal unlocked the cell door and swung it wide open.

Newt followed him to the front office. The marshal went to a cabinet behind his desk, opened it, and pulled out a holstered pistol with its gun belt wrapped around it. The pistol’s walnut grips had little turquoise crosses in-layed into them, same as the little blue crosses on Newt’s hatband. The marshal laid the weapon on the desk in front of Newt.

“I’m expecting not to see you again. Try and see to it that you don’t let me down,” the marshal said.

“The thought of disappointing you gives me shivers.”

The marshal let the sarcastic remark go by without comment. He went to a rifle rack mounted on the wall and took down a big-bore ’76 Winchester with a shotgun butt plate and its octagonal barrel cut down to carbine length. He sat that second weapon on the desk beside the pistol.

“Your horse is waiting at the livery down the street. I had him brought up out of the city pasture yesterday. Go get it and move on,” the marshal said.

“I’m a free man same as you, and I’ll go or stay where I please,” Newt replied.

The marshal shook his head. “Damned if you might not be the hardest-headed fellow I ever locked up. Let me fill you in on something. This is my town. If I say you go, you go. You don’t get gone, then I lock you back up. Savvy that?”

“On what excuse?”

“You got a job other than fist fighting for prize money?”

“No, but maybe I aim to find one,” Newt said. “Maybe I aim to run for city marshal next election just to spite you.”

“No job, huh? That makes you a vagrant. The Judge usually gives three days for that,” the marshal replied in a deadpan voice. “See what I’m getting at? This town doesn’t want you here. I don’t want you here. Your kind is nothing but trouble and we like to keep it real quiet.”

“My kind?” Newt took up the pistol, unrolled the belt, and swung the rig around his waist and buckled it.

“Against city ordinance to wear a sidearm on the streets. The Judge’ll give you another seven days for that.”

Newt gave the marshal a hard look. “Like you said, I’m leaving. I wasn’t hunting trouble when I came, and I’ll leave the same way.”

Newt shucked a Smith & Wesson No. 3 .44 from the holster, broke it open, and found the cylinder chambers empty. He closed the pistol and shoved it back in its holster. When he worked the lever on the Winchester and cracked open the action he found that it was unloaded, as well.

“Plenty of time to load them when you’re gone,” the marshal said. “I’d rest easier that way.”

“Nervous sort, are you?”

“I’m cautious is what I am,” the marshal answered. “I wired over to Los Angeles and other places about you when I first locked you up, and then I talked to Virgil Earp down at Colton. Figured a man with a face and attitude like yours was liable to have gotten into trouble elsewhere.”

There had been a time when someone mentioning his face would have caused Newt some discomfort, but he had long since grown used to that. It was his face, and there was no changing that, not when it looked back at him every time he stood in front of a mirror. It was a long-jawed, blunt-chinned mug marred by fists and about everything else that could be used to crack a man’s face open. Plain to see were the marks of a lifetime of fighting; scars and more scars, from those over his cheekbones and both eyebrows, to his crooked nose that had been broken more than once, and the lumpy gristle of a cauliflower ear.

“Man with a name and attitude like yours, I half expected there to be papers on you,” the marshal continued. “But the only one that had anything to say was Earp. Said he’d seen you box a match in the New Mexico Territory a few years back. Said you have quite a reputation as a scrapper out that way, but nothing more than that. Then again, Earp’s about half outlaw himself, and I don’t know if I’d believe everything that cripple-armed devil says.”

“Hate to disappoint you that I ain’t the desperado you hoped I’d be,” Newt answered.

The marshal was still looking up at Newt’s face. “Tarnation, son, maybe you ought to duck once in a while or pick up a new profession.”

Newt grinned back at the marshal just to spite him. He had his fill of the proper little lawman’s know-it-all attitude.

The marshal eyed the guns he had handed over to Newt. “You go awfully well heeled for a man that makes his living with his fists.”

“If it’ll make you feel better, I’ll rob a train or something on my way out of town.” Despite the way Newt sassed the marshal, his release from jail was steadily lifting his spirits and wiping away his surly mood. Maybe the day would get better and better.

The marshal frowned and made as if to say something in reply.

Newt cut him off. “What about O’Bannon?”

“You mean that promoter that was tacking up your fight posters all over town?” the marshal asked, even though he knew good and well whom Newt was talking about. “We’ve been over this a thousand times. He lit a shuck before I could lay hands to him, him and that fellow you were supposed to fight. Last I heard, they were headed for the coast.”

“And you don’t have any more idea of where he went than that?”

“Your guess is as good as mine.”

“Ed O’Bannon owes me one hundred dollars for showing up for his fight,” Newt said. “He guaranteed me.”

“You ought to be more careful who you trust.”

“That ain’t all, and you know it. When you brought me my belongings after you locked me up, there was seventy-five more dollars missing out of my saddlebags,” Newt said. “I’m assuming you didn’t take it, so that leaves O’Bannon, considering I left my things in his hotel room before the fight.”

“Maybe you’ll have better luck catching him than I did. Although, I’d say not. That Irishman struck me as a shifty one.”

Newt turned and started for the door that led to the street.

“I meant what I said,” the marshal called after him. “I expect to see you riding out of town as soon as you get your horse. Maybe I’ll even come along to make sure you do.”

Newt stood with the door open and the doorknob in one hand. He looked across the street at the group of men still gathered at the boardwalk in front of Kerr’s Emporium talking quietly among themselves.

“What’s that about?” Newt asked.

The marshal took a few steps forward until he could see out the door, and his white mustache wrinkled in a grimace. “None of your concern.”

Newt went out the door with the marshal on his heels. They walked down the opposite side of the street from the gathering in front of the store, but Newt kept glancing at the men across the way. The marshal was doing the same, and the frown stayed on his face as if there was something going on he didn’t like.

“Damned fools,” the marshal said under his breath like he was thinking aloud without meaning to. “He’s got half of them believing him.”

“Believing what?” Newt asked.

The marshal picked up his pace and nodded at the barn ahead of them. “There’s the livery where I parked your horse. I’m done talking to you, and I’m missing my breakfast. Mrs. Tillerman doesn’t like it when I let her food get cold.”

Newt listened to his own stomach growling and started to say something about where the marshal could stick his breakfast, but shook off the urge and stepped into the hallway of the barn. There was hay stacked on one side and a line of horse stalls on the other. Only one horse was inside the barn, and it hung its head out over its stall door and with perked ears looked at Newt.

Newt opened the door and stepped out of the way, not even bothering to halter or bridle the horse. A short, stocky brown gelding stepped out of the stall. It trotted down the hallway slinging its head and feeling frisky, but turned back and came to a stop in front of Newt.

“If I didn’t know better I’d think you missed me,” Newt said to the horse.

The gelding yawned and shook its head, then gave Newt a shove in the chest with its muzzle.

“Wouldn’t admit it if you did, would you?” Newt said as he slipped a bit in the gelding’s mouth and the bridle behind its ears before bending down to pick up his saddle and saddle blanket off the ground in front of the stall.

He slung the blanket and saddle up on the gelding’s back and looped the latigo through the girth ring and cinched the saddle as tight as he could at the moment. The gelding puffed its belly out, an old trick to avoid being cinched tightly, and Newt stood there waiting for the horse to give up. There was a bored look on his face and an equal expression and attitude on the horse’s part, as if it was an old game between the two of them.

“That was a fool stunt turning him out of the stall like that,” the marshal said from where he stood leaning against a barn post. “He could have ran off and trampled somebody on the street.”

Newt led the horse a few steps up the barn hallway and then back again. The gelding finally let out a groan of air, unable to hold its breath any longer, and Newt gave his cinch a last tug at the same instant the horse’s belly shrank. He shoved his Winchester down in the saddle boot hanging from the swells.

The liveryman came around the corner at the far end of the barn. He was a short, nattily dressed Mexican fellow with a neatly trimmed mustache and a brown suit. He had a game leg of some sort, like one of his knees was stiff, and he hobbled his way down the barn hallway to Newt.

He took hold of the narrow-brimmed derby hat and cocked it back on his head and gave Newt a look, and then he rubbed a hand over the odd brand on the gelding’s hip, a simple circle with a dot in the middle of it.

“This caballo, you get him from los Indios?” the liveryman asked.

Newt nodded, not sure how the Mexican knew that. “Fellow once told me that brand’s supposed to be some kind of Indian medicine wheel.”

The Mexican looked thoughtful and acted as if he was about to say more about the matter, but didn’t and simply shrugged his shoulders and shook his head somberly. “¿Quién sabe?”

“Who knows?” Newt repeated with a shrug of his own.

Newt paid the Mexican two bits for the keep of the horse, and found that expenditure left him with nothing but thirty dollars in his poke, all that remained from his working the docks at San Francisco Bay for the better part of the winter and well into summer. He had been counting on a healthy stake from the prizefight to go with what he’d saved before the marshal put an end to the event just as it was getting started, and before Ed O’Bannon robbed him. But thirty dollars was thirty dollars, and it was more than what he’d started with when he first pulled up stakes and gone west. And he remembered his boyhood when thirty dollars would have seemed like a fortune, or as Mother Jones used to say back in those old Tennessee hills, “a queen’s ransom.”

Thinking of his mother made him laugh out loud. She had known about as much about a queen as a long-eared mountain mule knew about a Thoroughbred racehorse, but she had a wisdom of her own and a mind as sharp as a skinning knife, she did. He missed her greatly, even after all the years.

Lost in memories, it took him longer than it should have to notice that the Mexican liveryman seemed to be waiting around for him to leave as much as the marshal was.

“You expecting something?” Newt asked.

The Mexican shrugged again. “I sent my boy down to get him and bring him to the barn. This caballo threw him twice and he give up the saddle, no? My boy, he rides good, but he could not ride this one.”

“He’s a cantankerous cuss at times, but he suits me fine.” Newt gathered his bridle reins, stuffed a boot in the stirrup, and swung up on his saddle. The gelding didn’t move a hoof under his weight in the saddle, much less buck.

Newt noticed that Marshal Tillerman had left. Apparently, the grouchy old lawman was finally convinced that Newt was actually leaving town and had gone to make sure his wife’s biscuits didn’t get cold.

Newt rode the gelding to the end of the barn with the Mexican walking behind him but stopped at the edge of the street and looked again at the group of men gathered in front of the store. He was a little shocked to see that the marshal had joined the group, especially given the marshal’s earlier disdain for the proceedings. The Mexican came up beside the horse and had a look at the group.

“That must be a hell of a story that fellow over there’s telling,” Newt said.

“Señor McCluskey, he says he saw the ship. Says he saw it sticking out of the sand,” the Mexican replied. “I think they are going to go back with him and find it.”

“Ship?”

“Will you go with them?” the Mexican asked after a long moment of silence. “I think maybe I go.”

Newt adjusted his hat brim against the sun and glanced down at the Mexican. “Go where?”

The Mexican gave Newt a look that was instantly cagey and filled with suspicion. “You don’t want me to go. I see that now. That is the trouble with such a thing. Who can you trust, no?”

“Does everybody in this town talk in circles?”

The Mexican looked up and down the street, as if searching for any eavesdroppers that might overhear him, his expression even more serious than before. Newt started to touch a spur to the Circle Dot horse and move out on the street, but the Mexican took hold of the gelding’s bridle.

“You have a good horse. Guns. I have a good horse and guns,” the Mexican said in a quiet voice. “Maybe we are partners. Nobody would cheat us that way. ¿Qué piensas?”

“Partners in what? For the last time, where is it you think I’m going?”

And then a slow, crafty grin spread across the Mexican’s mouth, as if they both shared a secret. “After the treasure, what else?”

The hour had grown late, and the petite woman hovering over the faro bank in a back room of the Arrowhead Springs Hotel shoved a slim cigar into one corner of her mouth. The cigar wasn’t in keeping with the fancy New York dress she wore, nor with the mother-of-pearl-and-silver Spanish hair comb tucked at the back of her head above the stylishly curled locks of brown hair draping to her shoulders, but she puffed on it with the steady rhythm of a train engine huffing coal smoke. Her blue eyes twinkled as she played idly with the brooch pinning the lace collar of her dress together. The pointer finger of her other hand tapped at the card box while she stared at the three men seated across from her through the tobacco smoke that wafted in slow-writhing tendrils beneath the lamplight.

“Praise the Lord and place your bets. I’ll take your money with no regrets,” she said in a playful, teasing tone with a hint of an English accent.

The player farthest to her right scowled at the thirteen-card faro layout on the table before him, shook his head, and stood and gathered what little chips he had left in front of him. “Not me, Alice. I’m done. Your game’s too tough for me tonight.”

The woman called Alice paid him for his remaining chips and watched him go halfway out of the room before she turned her gaze back to the remaining two players. One was an older man with cowlicked hair and curly white muttonchop sideburns down his jawline. His suit coat was draped across the back of his chair and his shirtsleeves were rolled up to his elbows. Earlier in the day she had observed him hawking some kind of wares to one of the staff in the hotel lobby, and assumed he was some sort of a drummer or traveling salesman. That was only a guess, but he was talkative enough to fit the profession, a real chatterbox with a line of blarney for everything. However, his glib banter had fallen away and he grew more sullen as the evening progressed and his losses mounted. The stack of gambling chips in front of him was even more meager than that of the man that just left the game. And it didn’t help that he drank too much whiskey throughout the course of play. The half-empty bottle on the table beside him gave testimony to that. He glared at her and muttered something under his breath that she couldn’t quite make out.

Dealing with drunks and sore losers was old hat to her, but the game had gone late into the night and her patience was wearing as thin as the dim light that bathed her faro table. She ignored the complainer and glanced at the cowboy beside him. He was young, hardly more than a kid in her book, but a good-natured kid, at that—big hat, spurs, and a devil-may-care grin no matter how the game was going.

He caught her looking at him and smiled. “Seems like you’re about out of punters.”

“What about you? You calling it quits, too?” she asked.

He leaned back in his chair, stretched both arms out to his sides, and gave a mock yawn. “Roosters will be crowing before long, and besides, you’re dealing too many pairs to suit me and I like a full table of punters and a fast game.”

She nodded and began to change out his chips. Despite his complaint about a tough game, she noticed that he had lost little, if anything. He had been a shrewd bettor, no matter how young he was or how much the game had turned in her favor over the last hour.

The old drummer glared across the table at her and slammed a fist down on it for emphasis. “I say you cheat.”

The floorboards creaked directly behind her and a big man moved from the shadows to stand protectively at her right shoulder. Even in the dim light, he was a striking man, and not only because he was a giant.

He placed both of his oversized palms on the table’s edge, ducked under the lamp overhead, and leaned closer to the drummer. That swath of lamplight revealed a broad, square-jawed face covered almost entirely in dark blue tattoos—chevronlike bars across the breadth of his forehead, and T-shaped designs of dots and lines running down from both cheekbones to intricate swirls on his blunt chin. His long black hair was pulled back tightly and tied behind his head with a leather thong, making the angles of his face seem sharper and more severe. The long-tailed frock coat, vest, and tie he wore would have been at home on the streets of any city, but no one looking at him would have mistaken him for a metropolitan gentleman. The suit was decidedly civilized, but in that moment, his gaze was pure savage. He leaned his weight on the table, staring out of his obsidian eyes at the old man, yet not saying a word.

“Easy, Mr. Smith,” she said as she glanced out of the corner of her eyes at the giant Indian beside her. “This gentleman is just having a tough run of luck and didn’t mean anything by it.”

“Like hell I didn’t.” There was a quaver in the drummer’s voice, and the presence of the big Indian didn’t check him at all. “I’d like to have a look at your card box, I would, by damn.”

“I would

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...