- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

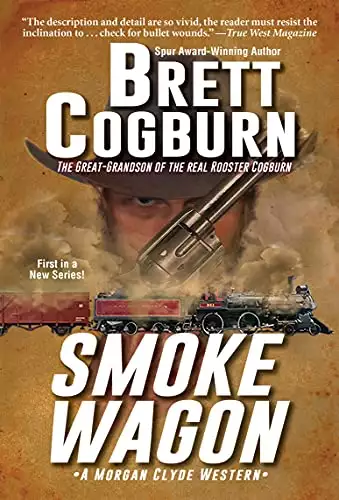

Spur Award winner and bestselling western author Brett Cogburn crafts a post–Civil War railway thriller.

Last stop on the train ride to hell.

Welcome to Ironhead Station, Indian Territory, where the train tracks end and the real action begins. The hell-on-wheels construction camp is the final destination for hard-drinking sinners, gamblers, and outlaws. And woe to the man who tries to clean it up.

Morgan Clyde is a former New York City policeman and Union sharpshooter who lost everything in the Civil War. But he’s still got his guns and his guts. Some folks say he is meaner and tougher than the Devil himself. Which is why the owners of the MK&T Railroad hired Clyde for one hell of a job. They plan to extend the rails through Indian Territory, connecting Missouri and Kansas to Texas … But the ornery citizens of Ironhead Station want to keep things just the way they are. They’ve already killed the first two lawmen who tried to tame their town. Now they’ve put together a welcome wagon to greet Clyde, including one half-mad preacher, one hillbilly assassin, and twenty train-robbing bushwhackers. They’re laying plans to stop the railroad dead in its tracks—along with their new lawman.

There’s just two things the folks of Ironhead Station didn’t take into account: you can’t stop the wheels of progress. And you can’t stop a legend like Morgan Clyde.

Release date: December 28, 2021

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 398

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Smoke Wagon

Brett Cogburn

The first thing that struck him was the noise of so many people moving about the camp: men shouting to each other or cursing wagon teams, the pound of hammers and the rasp of saws where a crew was working to raise the frame on the new depot house, and someone banging away on an out-of-tune piano down the street.

The second thing that hit him was the smell—the smell and the filth.

It had rained recently, and the one so-called street was nothing more than a mud lane running straight as a Cherokee arrow through the tents and false-fronted, canvas-roofed businesses lining either side of it. Water stood in the low places and in every hoof divot and wagon rut. And it wasn’t only mud and rainwater. Horse and mule manure, dog feces, emptied chamber pots, and trash all mixed freely into the viscous soup that the street had become, until the whole camp looked and smelled like a hog pen.

The letter he had received claimed that there were, at last count, three hundred souls in the construction camp, but here it was a little past midday, and with most of the railroad crews still out working, the street was teeming with people, wading and cursing their way across or along the street. Wagon wheels sank to the hubs in bottomless ruts, and the mule teams pulling them worked hock deep with their ears flattened and their backs humped against the strain of the mud sucking everything down, down, down. Their trace chains popped each time the mules lunged forward, and the drivers shouted at pedestrians to get the hell out of the way before their wagons stalled out and became stuck.

Boards had been laid as walkways in places, but most of the boards had already sunk below the surface. Staying even reasonably clean was impossible in the shin-deep quagmire. Everyone in sight was muddy from the knees down, and some worse.

A drunk came out of one of the tent saloons and sank to his knees in an especially deep hole. The suction of the mud took hold of one of his legs, and he windmilled his arms wildly to catch his balance until he fell face first in the street. He was soon up on his feet again, coated from head to toe in good old Indian Nations mud, and looking for the boot that had been pulled off his trapped foot. A wagonload of logs was about on top of him, and he lunged away just as the lead mules trampled whatever chance he had of ever recovering the lost boot. The wagon’s driver and the drunk exchanged loud insults, but the wagon inched on toward the tracks.

Morgan took it all in with his face as hard and still and expressionless as an Indian’s, his ice-blue eyes gauging the scene before him like an undertaker measuring a man for a coffin. He shook out the match and flipped it to the ground in a smoking arc.

Somebody shouted near the bare-bones frame of the new depot house, followed by catcalls and boisterous laughter from several more men near the train. A pistol cracked, and out of instinct and reflex, Morgan’s hand took hold of the Remington’s grip. The people behind Morgan in the doorway of the passenger car flinched and ran into each other trying to get back inside. It only took Morgan an instant to spot the culprits. A young black man dressed like a cowboy in tall-topped boots and a red silk neckerchief, and two Indians dressed much the same, had their pistols out and were shooting them into the air. They paraded up and down the depot platform like strutting roosters.

At least fifty people were gathered alongside the newly arrived train, either as passengers or gawkers from the camp. The first pistol shot quieted the crowd, and then they scattered like quail flushed from the tall grass when all three of the drunken cowboys fired a second volley. A buggy mare spooked so badly that she kicked one of her buggy shafts in two, and fell on her side and became tangled in her harness.

“Welcome to the Indian Nations, you train-riding sons a bitches!” the black cowboy shouted and took off his broadbrimmed hat and waved it in a circle above his head.

One of his companions whooped beside him, and then leaned back his head and did his best imitation of a coyote yipping at the moon. He had a pint bottle of whiskey in one hand, and his pistol in the other. “Gonna scalp me a tenderfoot before today’s over.”

One of the carpenters up in the rafters of the depot house flung his hammer at the black cowboy, nearly striking him in the skull. The black cowboy popped off a shot at the hammer-flinger, but the carpenter was nimble and smart enough to dodge amongst the rafters. The shot went wild, and it didn’t help the black cowboy’s aim that he was sloppy drunk and reeling on his boot heels. He was still peering up in the rafters with his pistol cocked and hoping for another shot at the carpenter when one of his Indian companions hissed a warning at him.

It looked like one of the railroad crews was coming up the street with its attention on the trio causing the ruckus. Every one of those railroad workers was carrying a club or a sledgehammer or some other kind of bludgeoning instrument to adjust the behavior of the men doing all the hell raising. The black cowboy forgot about the hammer-flinging carpenter, and he and his comrades began to slip away through the crowd, trying to put distance between themselves and the railroad gang coming their way. The whole episode ended as quickly as it had begun.

“You’ve got to be kidding,” the woman behind Morgan said.

She was middle-aged, portly, and wearing a little bonnet as prim and sour as the look on her freckled, big-nosed face. Her husband, two inches shorter than her and half her weight, stood behind her in the passenger car door with a pipe clenched in one corner of his mouth. A mass of curly hair red hair stuck out from under the wool cap he wore.

“It’ll be all right, Mother,” her husband said.

“Where’s the law?” She gave an indignant huff.

“There ain’t no law in Ironhead Station, Mother. None at all.”

“Lord, help us.”

“They say there ain’t no church west of St. Louis, and no God west of Fort Smith, neither,” the husband added.

“Shame on you. Take that blasphemy back right now.” The woman immediately slapped him hard on the shoulder.

Morgan let go of his pistol and continued to listen to the pair’s conversation while his eyes followed the trio of hellions’ retreat down the street. Apparently, to hear him talk, the woman’s husband had been in the camp before.

“They’ve appointed two marshals: one a former Yankee officer, and the other a Texan. But neither of them lasted longer ’n the time it takes to spit,” the husband said. “First one turned in his badge his first day on the job and caught the next train north. Had his fill of it, and was glad he didn’t ride out of here lying on his back. The second one, that Texan, wasn’t so smart, but he had more guts than a slaughterhouse. Lasted a whole three days before Texas George picked a fight with him and shot him dead.”

“Sodom and Gomorrah is what I see. We should’ve have stayed in Carthage,” the wife said.

“We’ve already talked about this a hundred times if we’ve talked about it once. If you want to go back to Missouri, you can. It ain’t like I didn’t try to tell how it was going to be.”

The wife shook her head. “No, we’ll stick. Can’t be a family with us back home and you down here. We’ll have to find a way to get by, that’s what we’ll have to do.”

“They’re always like this,” Morgan said, almost as if talking to himself.

It took the man and woman a bit to realize that it was he who had spoken, so quietly had he stood before.

“Begging your pardon?” the husband asked.

Morgan exhaled a cloud of cigar smoke and turned to them. “I said, these end-of-the-tracks construction camps are always like this.”

“Yep, but this one’s way worse than most, and it’s gonna be wild for a while,” the husband answered. “That trestle across the South Canadian has things held up. They bridged the North Canadian without a problem, but this one is a whole ’nother animal. The first one they built on the south fork of the river collapsed on them, and then some of the local badmen tried to burn down their next attempt. This railroad ain’t never going to get across the Territory if they don’t get that bridge built, and there’s more and more men packing into Ironhead Station every day—most of them the kind that you’d rather not see around.”

“Is that what they’re calling it?” Morgan asked. “Ironhead?”

“For now, until it catches fire, or somebody comes up with a better name.” The husband chewed on his pipe stem and made a clicking sound in his cheek. “The railroad’s laid off more than half its men until the bridge gets built and they can start laying track again. Most of those they laid off are still hanging around with too much whiskey and too much time on their hands, and word’s gone out across the Territory that the company is stalled out here. Every holdup artist, tinhorn gambler, whiskey peddler, and pimp and sporting woman in the Nations is either here, or on their way here to get in on the action.”

“Hank!” the wife said. “Watch your talk.”

The husband gave a fake grimace that was meant as an apology, but continued, regardless. “I’ve only been gone a week, but I already see another tent saloon that wasn’t here when I left and about twice as many people.”

“I know it sounds bad of me, but the Lord ought to strike this whole place down.” The wife interrupted Morgan’s thoughts. “Turn the whole thing to nothing but a pillar of salt and then wash it clean with a flood.”

“Please don’t mind the Missus. My Lottie is a God-fearing woman, but she just ain’t used to all this.” The husband set down an armload of luggage, and held out his right hand to Morgan. “Name’s Henry Bickford. Everyone calls me Hank.”

Morgan shook with him, surprised at the hard strength in the little man’s calloused grip. “Morgan Clyde.”

Hank Bickford pumped Morgan’s hand, but leaned back as if to get a better look up at him upon hearing his name. There was a measuring and cautious look on his face, and he gathered his words carefully before he spoke again. “Pleased to meet you, Mr. Clyde.”

“My Hank is a horseshoer and blacksmith for the line. What brings you here, Mr. Clyde? What line of work are you in?” the wife asked, oblivious to the warning look on her husband’s face.

Morgan reached down and picked up his single little leather valise and the bedroll he had left on the deck while lighting his cigar. Hank Bickford noticed that the bedroll was wrapped around a suede leather rifle case.

“You might say I’m a troubleshooter.” Morgan smiled around the cigar, as if it took an effort for the muscles of his face, and as if it were an unnatural expression for him.

“Troubleshooter?” the wife asked. “What kind of job is that? Are you here to get the bridge built?”

“You might say that. Good day.” Morgan tucked his belongings under one arm, tipped his hat to them, and started down the steps.

Hank Bickford waited until Morgan was off the train and several yards away before he picked up their luggage again.

“Seemed like a nice man for a Yankee,” she said. “Although, that was kind of rude for him to walk off like that without answering my question.”

Hank didn’t reply to her, still watching Morgan’s tall form winding its way through the crowd of people headed for the company headquarters. Lottie tightened her shawl about her neck and shoulders and stiffened beside him when she noticed a pair of prostitutes standing alongside the tracks with nothing but skimpy wraps over their underclothes, and calling out ribald jokes and loud, lewd innuendos to a group of men at work unloading equipment off a flatcar.

“Those girls sure must be hot natured to go with so little clothes,” Hank said.

Lottie elbowed him in the ribs and pulled her children close to her, hugging them to either side of her broad hips like little chicks underneath a mother hen. “This is the devil’s playground if ever there was such a thing.”

Hank gave her a half-hearted, worried smile, and then nodded his head at Morgan’s back. “Maybe so, Mother, but the devil didn’t show up until today.”

“Him?”

“Yes, him. You might say hell’s come to breakfast, sure enough.”

“If you won’t mind your talk in front of me, then remember our children.”

“Sorry, Mother, but that’s the pure truth.” Hank’s attention turned to the construction crew still chasing after the trio that had been hoorahing and threatening the train’s arrival. He shook his head somberly and almost regretfully while looking over the camp, as if standing over a friend’s grave at a funeral and mourning his passing. “And these poor amateurs don’t even know what’s coming. But they will soon enough. You wait and see. Won’t be long until word gets out all through this hell-on-wheels that Morgan Clyde has come to town.”

The railroad company had its office at the end of the platform alongside the depot house under construction, and on the corner facing the head of what passed for a main street. It was a single-story, two-room frame affair with a canvas wagon tarp for a temporary roof, and green-sawn yellow pine planks still oozing sap for siding. But however hurriedly and shoddily it was built, it did have the only boardwalk in town in front of it, consisting of a narrow ribbon of small logs laid side by side in a corduroy fashion, and a man could at least keep his feet dry. Morgan glanced at the sign over the front door. MK&T RAILROAD OFFICE, IRONHEAD STATION, INDIAN TERRITORY. Two tough-looking men sat in chairs to either side of the door, and both of them had shotguns laid across their laps.

He weaved his way through the crowd on the boardwalk, and nodded at the two guards. Neither of them spoke to him, but they didn’t stop him from going inside, either. The front room consisted of a table piled with all kinds of ledgers and various other clerical papers, and a single chair behind it. Apparently, the clerk was gone on other business, but Morgan heard voices coming from an interior doorway to the rear of the office.

Three men stopped their conversation and looked his way when he stepped into the back room. One of them was a short, stocky, bulldog of a man, a tick past middle-age, and dressed in a tailored suit. He sat at the back of the room, reared back in his office chair with his fingers laced together over the belly of his paisley vest and his feet propped up on one corner of his office desk. Both of his jaws were covered in mutton-chop whiskers, combed and waxed and sticking out like wings, and his hair was oiled and parted with perfect precision down the middle of his skull. His blue-gray eyes were like glass when he glanced at Morgan in the doorway, and an impatient frown crinkled his mouth.

Another man stood at a large set of plans and draftsman drawings of the river bridge pinned to the wall. He was young, and unlike the man at the desk, he was dressed in rough work clothes with his sleeves rolled up to his elbows and his thumbs hooked in his suspenders. His lower body, from his canvas work pants to his lace-up boots, was covered in a thick layer of dried mud.

The third man sat in a chair at one end of the desk. He was tall and scarecrow thin, with a stoop to his narrow shoulders and a hump in his back to match a young buffalo’s. Like the man behind the desk, he was dressed in a suit; however his wasn’t nearly so expensive or neat. Everything about him was wrinkled and haphazard, from his threadbare jacket, to his untied string tie, to the crooked way his eyeglasses sat on the bridge of his beak of a nose.

“If you’re looking to hire on, you need to come back when the clerk is in,” the man behind the desk said in a tone of dismissal. He turned his attention back to the drawing on the wall, as if he had forgotten Morgan’s presence already.

Morgan set his belongings down, leaning the end of the rifle case against the wall, and reached in his vest pocket and pulled forth an envelope. He crossed the room and pitched the envelope on the desk in front of the man.

“Your letter said you’d pay me fifty dollars for coming down here and looking things over, and I’ve looked it over,” Morgan said.

“See here, we’re holding an important meeting,” the stooped man at the end of the desk said.

The man behind the desk held up a hand to quiet him, while he eyed the letter and then stared at Morgan as if seeing him for the first time. “Hold on, Euless. I did send for this man.”

The one called Euless gave Morgan an expectant look, as if waiting for a name. Morgan ignored him and focused his attention on the man behind the desk.

“Your answering letter said you would be here a week ago.” The man behind the desk had a midwest accent that Morgan couldn’t quite place—maybe Illinois, or Indiana.

“I was busy,” Morgan replied. “Are you Superintendent Duvall?”

“That I am.” The man behind the desk reached into a shipping crate behind his desk that served as a temporary cabinet, and pulled out a bottle of whiskey and several glasses. He set them on the desk. “Willis G. Duvall, MK&T Railroad, at your service. This man to my left is the agent for the Creek Indian tribe, Euless Pickins.”

The Indian agent nodded at Morgan. He was the odd one in the room—nervous and restless and continually shifting positions in his chair. Morgan noted how the man stared at the floor and rarely made eye contact, and how he picked at a scab on the back of one of his hands.

“And this Scotsman is my head construction engineer and foreman.” Superintendent Duvall pointed at the man in work clothes standing before the bridge plans on the wall. “Hope McDaniels, meet Morgan Clyde. Mr. Clyde is going to be our new chief of police.”

“Morgan Clyde!” the Indian agent blurted out before the engineer could reply. He made no attempt to hide his distaste at hearing Morgan’s name.

“Care for a toddy?” Superintendent Duvall tried to smooth over the embarrassing gaff by gesturing at one of the whiskey glasses on the desk.

“Business first,” Morgan replied.

“Have a seat then.” Duvall pointed at a spare chair.

“I believe I’ll stand.”

“Are you always so disagreeable?”

“No sense wasting any of our time.”

“Suit yourself.” Duvall poured himself a drink and pitched a tin badge on the table before he leaned back in his chair again. “You start today.”

Morgan didn’t even look at the badge, much less pick it up. “We need to sort out a few things first.”

“Go ahead.” There was impatience in the superintendent’s voice.

“One hundred and fifty dollars a month,” Morgan said.

“You never told me you were trying to hire this man,” Agent Pickins interrupted them again.

Superintendent Duvall made another dismissive wave of his hand at the Indian agent. “Let’s hear the man out, Euless.”

“I hire my own deputies, and you’ll pay them seventy-five a month,” Morgan said as if it were only he and the railroad superintendent in the room. “I won’t hire more than two of them.”

“Your price is too steep. That’s half again what you quoted me in your reply to my letter.”

“You get what you pay for,” Morgan said. “And I quoted you that first price before I had a chance to look this camp over. I’ve seen it now, and I think it calls for a premium on my services.”

“I suppose this is negotiable?”

“Those are my terms, take them or leave them,” Morgan said. “Normally I get a cut of the fines, too, but this place won’t be here long enough to set that up.”

“This is preposterous. You’ve no right to hire a marshal,” Agent Pickins said. “This isn’t a real town, nor will it be according to the terms the railroad has promised the Indian tribes.”

Superintendent Duvall pulled a folder from his file cabinet while the Indian agent was talking. He slapped the file down on the desk and thumbed it open, donning a pair of spectacles so that he could inspect the documents within it. “Morgan Clyde: Two years as a New York policeman. Quit at the start of the war to join up with Company A, 1st United States Sharpshooters, Berdan’s regiment. Decorated for valor at Malvern Hill and Gettysburg. Marshal of various cow towns: Sedalia and Baxter Springs. Last known job, U.S. Deputy Marshal for Judge Story’s federal court out of Van Buren, Arkansas.”

“I don’t need your report to know of this man’s reputation ...” Agent Pickins tried again, but wasn’t allowed to finish.

“Euless, I’ll remind you that we’re all gentlemen here, and that there’s little that you can add about this man that I don’t already know.” Duvall gave the Indian agent a sharp look and then closed the folder and slapped it with the palm of his hand like a judge’s gavel in a final verdict. “The Pinkerton Detective Agency put this dossier together for me as a favor.”

Morgan leaned over and rubbed his cigar out in the tin ashtray on one corner of the desk. “What else does that file of yours say?”

Duvall laced his hands together over his belly again and met Morgan’s hard look. “Among other things, it says you killed two men in Baxter Springs, and then another while you were working for Story’s court. Says you’re a damned hard man who’s too quick to shoot to suit the tastes of most of your employers. I heard myself that Judge Story fired you for shooting and wounding a prisoner who claimed his hands were shackled at the time of the incident.”

Morgan ground the cigar more firmly into the ashtray, unaware that he was crushing the stub of it. “Somebody’s a damned liar.”

“Maybe, but if I didn’t believe most of this report on you wasn’t accurate, I wouldn’t have sent for you. My job is to get this railroad to Texas, and yours will be to see that none of these secesh sons of bitches and renegade trash that have been holding up my trestle job get in my way again.” Duvall leaned forward until his face was closer to Morgan’s over the desk. “You can sweet talk them, kiss them, rock them in a baby cradle, or you can shoot every last living one of them between the eyes for all I care. This line has got to make it into Texas by the first of the year, and I want some by God law and order in this camp.”

“You should have discussed this with me first,” Agent Pickins said.

Duvall held Morgan’s stare a brief instant longer and then turned to the Indian agent. “It’s my company’s money that’s going to pay this man, and what do you care if I hire a railroad policeman to handle my camp?”

“Your line runs on Indian land, and as a duly appointed agent to the Creek tribe ...”

“My line runs on a right of way granted to me by the federal government.” Superintendent Duvall turned to the engineer at the bridge drawing. “What do you think, Hope? It’s your bridge.”

“Something has to be done.” The engineer already seemed to have lost interest in the conversation and he was studying the diagrams again.

“There you go, Euless,” Superintendent Duvall said. “Two votes to one. You’ve now been consulted with.”

“I agree we need a peacekeeper, but this man’s little better than an outlaw himself,” Agent Pickins said.

“You be careful before you go any farther with that line,” Morgan said quietly.

“I will not be bullied by the likes of you.” The Indian agent looked defiantly at Morgan, quickly adjusting the wire-rimmed eyeglasses on the bridge of his nose, but only managing to leave them more askew than they had been before. “We have no need for another ruffian in this camp.”

“I’ll not warn you again.” Morgan turned slowly to face the Indian agent, and the tone of his voice had changed.

Superintendent Duvall cleared his throat. “I don’t think striking a federal Indian agent and a man of the cloth will help your reputation any, Clyde.”

Morgan frowned at the Indian agent, as if reassessing the man. “Him?”

“I’m an ordained Methodist minister,” the Indian agent said, straightening a bit in his chair.

“Euless used to run the Ashbury Mission school for the Indian children, and he was appointed agent to the Creeks not long ago,” Duvall added. “He and his Indians have been howling to Washington about my right of way being granted without their approval.”

Morgan grunted. “You’ve heard my terms. Agree to them, or give me my fifty dollars for coming all the way down here.”

“And here’s my final offer,” Duvall answered. “Seventy-five dollars a month for you, and fifty dollars a month for your deputies. Have we got a deal?”

“Pay me my fifty dollars, and I’ll be gone.” Morgan turned to McDaniels, the engineer, while Duvall opened the safe behind his desk. “That’s quite a bridge you’re building.”

McDaniels nodded absentmindedly, and it took a bit to pull his attention from whatever he was thinking on. “Yes, yes, it’s a real corker. We made a good start on it once, but the first design was all wrong and the pylons didn’t hold and the whole bloody thing collapsed. And now we’ve got other problems.”

“Such as?”

The engineer shared a look with his superintendent, and only continued when Duvall nodded at him. “It seems some of the rough element in camp don’t want the railroad to progress past here. Somebody tried to burn the bridge down two weeks ago.”

“They’re fine with making their profit right here, aren’t they? And I’m guessing you’ve got a few saloon owners and a bunch of others that like having all the sheep they can fleece congregated in one herd.”

Again, a look was passed between the superintendent and the engineer, but like before, the superintendent showed his agreement with a simple nod of his chin. “There’s a bad mob of outlaws down in the thickets along the river. Not only do they cause problems in camp, but they robbed one of our wagon trains coming overland with supplies from Fort Smith two weeks ago. And the worst thing might not be all the criminal sorts, but the fact that I’m having problems getting all of my men to show up for work because they’re drunk and laid up in one of those tent saloons.”

Duvall held out Morgan’s money. “My offer still stands.”

“No deal.” Morgan took the mix of paper money and coins and counted them before shoving them inside his pocket. He pointed at the safe behind the desk. “Is that why you’ve got the guards out front?”

“Rented Pinkerton agents. I keep a little money on hand, but we wait to bring in the payroll from Kansas City each month.”

“Must be worse than I thought.”

“You aren’t the only peace officer for hire.”

“No, but I’m the only one that’s here.” Morgan gave a curt tip of the brim of his hat and turned and went out the door.

“Abrupt, isn’t he?” the engineer said when Morgan was gone.

“A difficult bastard, for sure.” Superintendent Duvall scowled at the door.

“You should count yourself lucky that he didn’t take your offer,” the Indian agent said after Morgan left.

Duvall didn’t answer him, and swirled his whiskey around in its glass and continued to stare at the door.

Agent Pickins knocked a bit of grass off of his rumpled coat and took up his hat from the rack on the wall. “Mr. Duvall, if you don’t get this camp under control, I will be forced to take action. You know that the sale of intoxicating spirits in the Indian Territory is against the law, as well as the fact that you are basically setting up a town here, rather than the station you originally promised.”

“My right-of-way grants me the roadbed and every alternate section of land alongside it.”

The Indian agent scoffed. “Save that for those that don’t read the newspapers. News travels fast, even way out here, Duvall. No matter what you say, Congress has revoked all but your roadbed rights. You know it and I know it. Much of your so-called grant has been deemed unconstitutional and illegal, and was never agreed to by the tribes.”

“It is still being discussed. Damned lawyers.” Duvall threw down the last of his drink and poured himself another one. “Shysters and crooks and liars, every one of them.”

“Unless Congress changes its mind, your authority extends nowhere beyond the narrow strip surveyed to lay your tracks.”

“Say what you mean, Euless,” Duvall said with color flushing his face. “Don’t beat around the bush if you are going to threaten me.”

Agent Pickins willed himself to lift his eyes from the floor and meet the superintendent’s hard look head-on. “I’ll go to the Board of. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...