- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

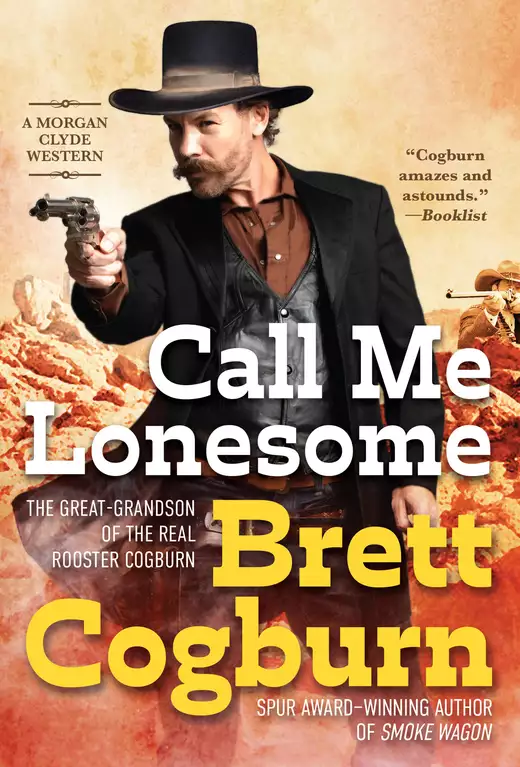

Two-time Spur Award–winner Brett Cogburn brings back the true grit and glory of the Wild West with his second post-Civil War thriller featuring New York City policeman-turned M&K Railroad lawman Morgan Clyde.

With a storm of hot lead he brought peace to the blood-drenched, lawless Ironhead Station, deep in the wilds of Indian Territory. Now Morgan Clyde, who fought criminals as a New York City policeman and Confederates as a Union soldier, has another war on his hands.

Wanted dead and buried

The bloody barbarism of the Civil War scarred Morgan’s soul as well as his body. He sent so many soldiers to Hell and almost joined them when he was struck by a bullet from the sniper known as the Arkansas Traveler. The only man to ever survive the notorious Rebel’s sharpshooting skills, Morgan finds himself back in the assassin’s sights.

But the ex-Confederate isn’t the only one gunning for Morgan. The outlaw Kingman brothers have followed him from Ironhead Station out onto the Salt Plains of the Arkansas River, seeking vengeance for their brother who Morgan killed in a gunfight. Then there’s the Pinkerton Detective agents, answerable to no law but their own, on a mission to execute him.

And as his enemies close in, Morgan strikes with the speed of a rattlesnake, the ferocity of a grizzly, and the predatory instinct of a stalking wolf …

Release date: April 26, 2022

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 480

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Call Me Lonesome

Brett Cogburn

After that gunshot had faded away there was no sound but the incessant buzz of a blowfly. The fly’s fat blue body flitted lazily about, drawn to the smell of guts and putrid death. The first shot had taken the horse in the flank and busted its paunch. A great loop of intestines and half-fermented belly juice had spilled out onto the ground while the horse thrashed and struggled in pain, and before the second bullet struck it in the head and put it out of its misery.

Despite the smell and the heat, and despite his cramped muscles and the fear, the man behind the dead horse remained still. He fought off the temptation to peer over his saddle enough to see if he could spot his attacker, for he knew to do so was to die. From the direction of the shots, the rifleman was positioned somewhere on the hilltop several hundred yards on the far side of the dead horse, which now sheltered him, and a man that could hit a horse in the head from so far away was a man that could hit about anything he wanted.

It was an old game that the man behind the dead horse knew well, and the primary rule of that game was that the first one to make a wrong move died. The second rule was that there was no second-place winner.

He pushed tighter against the horse carcass and looked up at his rifle stock, which he could see protruding out over the animal’s flank. He wondered how quickly he could draw the gun out from under his stirrup leather, and how much of himself he would have to expose by doing so and for how long.

A cackle of laughter sounded from out there on that far-off hilltop, wicked and raspy, and more than half-crazed.

“Clyde,” the same voice called out, and it drug out the name so slow that it was like an echo.

The man behind the horse didn’t answer.

“Hey there, Clyde,” the voice repeated.

The man behind the dead horse did not want to hear that voice, but he was not shocked at the sound of it. He had known all along who was out there, without so much as laying eyes on him. And that was the bitterest thing of all—lying there knowing he had been ambushed by the man he himself had sworn to kill. But that was another rule of the ancient, bloodthirsty game of men hunting men. The hunter often turned into the hunted.

Red Molly O’Flanagan fanned the sweat-damp curls of red hair plastered to her forehead with one hand, and her bosom heaved as she sucked in a breath of heavy, humid air while she sat on the bench in front of the ruined shell of what had once been the depot house. Carpenters hired by the railroad had already torn most of the building down. Only the single wall behind her remained standing, charred from fire and leaning precariously, and with the planking shattered and blown off in places.

The man beside her on the bench wore a sweat-stained, gray wool Johnny Reb cap, and held a pipe clenched between his jaw teeth on one side of his mouth. He coughed when he drew on the pipe, and had to put it aside while he hacked up smoke and phlegm and spat it off the depot platform into the street.

“You ought not be smoking with that lung of yours still mending,” Red Molly said, her accent laced with more than a touch of the Irish brogue.

The man in the Rebel cap touched a hand to his chest, but said nothing to that. Instead, he continued to watch the work crews the length of the street dismantling tents and the plank false fronts of what had been most of the railroad camp’s structures. They worked like a steady stream of ants, tearing things apart, carrying those things to the train cars parked on the tracks at the head of the street, then returning to repeat the process.

“They’ll have the whole camp torn down and loaded up by dark,” Molly said, more to herself than anything.

“Not all of it,” he replied. His slow, Alabama drawl and country twang was almost as heavy as her Irish brogue. “Some of those people that moved over from North Fork are staying, and I hear Bill Tuck’s gonna keep his saloon here. I don’t know what they’re thinking with the railroad pulling out.”

“They’re thinking they’re going to build a regular town,” she said. “Simple as that.”

Both of them continued to watch the tent camp torn down, each lost in their own thoughts. The idling locomotive parked close by them was drifting a cloud of smoke and cinders over everything.

A troop of black cavalry soldiers rode up the street, and the white officer leading them reined his horse over close to the depot platform. He didn’t stop, but he tipped his hat brim to Red Molly and the man in the Rebel cap.

“It’s all yours,” the officer said to the man in the cap. “Good luck.”

The cavalrymen crossed the tracks, heading north, and were soon out of sight. A few of the men at the train stopped their work to watch the soldiers pass, and more than a few of them mumbled harsh words about the army.

“Not everybody loved those sodger boys’ heavy-handed ways,” the man in the cap said.

“I’m glad they came, but at the same time, I can’t say I’m sorry to see them go,” she answered.

The man in the cap nodded his head in agreement. “First time I’ve seen martial law since the war, but like you say, it was needed, no matter what some of them cutting their eyes at those sodgers think.”

She looked behind her at the pitiful remains of the depot house. Bits of shattered window glass and splinters of wood littered the boardwalk, the depot platform, and the ground around it. “If they had only come sooner . . .”

He gave the destroyed depot house a glance and sniffed the air. “I swear I can still smell that burnt nitroglycerin like it was yesterday. Should have known not to put anything past that Missouri border scum. Dangling a railroad payroll in front of them was like hanging raw meat in front of a wolf’s nose.”

“The Katy people were going to paint the depot maroon like their locomotives.” She referred to the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad, the MK&T, like all the locals did, as the Katy. “Would have been a pretty building beside the tracks. First thing you would’ve seen when you came to Ironhead.”

“Ironhead don’t look like much now, does it?” he asked. What had been the main street was now only a strip of hoof-torn earth running in an arrow-straight line through rows of brown squares where the grass had been beaten away for tent floors. Where once the wagon yard had been, there was nothing but trash littering the grass. And the depot house wasn’t the only black scar on that strip of has-been street. Bits of charred tent framing and an ash pile marked where Irish Dave’s Bucket of Blood saloon had stood.

They listened to the screech of a nail as someone down the street tried to pry it loose from the bite of the wood it was driven into, and watched a man beating a mule towards the railroad tracks dragging a sled load of salvaged pine lumber with a cast-iron stove piled on top of the stack.

“Who’s gonna run Bill Tuck’s saloon for him?” he asked.

Red Molly didn’t answer him. She pulled a white lace handkerchief from her wrist purse and coughed into it several times.

“You sound like you’re getting sick,” he said when she was through.

“It’s nothing. This spring weather has given me the croup. Hot one day, cool and wet the next.” She glanced down at the handkerchief, and then folded it quickly and put it away.

He tapped his pipe bowl against the heel of one boot he had propped up on his knee, and watched the ashes fall out of it onto the boardwalk. “You didn’t answer my question about Tuck’s saloon.”

“No, I didn’t.”

“That’s what I thought.”

“What did you think?”

“You’re gonna run the Bullhorn Palace, ain’t you?” He scraped at the inside of the pipe bowl with the blade of a small pocketknife he pulled from his vest pocket and glanced at her out of the corner of his eye.

“Tuck asked me,” she said.

“Wouldn’t have thought you would work for the likes of him. Not after everything he’s done.”

“I said he asked me. Never said I accepted.”

“I can tell.”

“Just what can you tell, Dixie Rayburn?” Her green eyes widened and bore down on him, and her large breasts heaved again as if she was drawing a breath and about to say more.

The man she called Dixie looked at her with a bland expression. She was truly a pretty woman with thick, dark red hair and a figure that made most men look twice at her, and a smile, when given, that could light up a room. But all the same, he noticed the faded, faint yellow bruises on her face mostly covered by the rice powder she wore, the smear of some kind of red lipstick on one corner of her mouth, and the sweat-soaked dress where it pressed between those two great breasts. He also noticed for the first time the wrinkles at the corners of her eyes and the way her skin hung looser on her jaw. And then there was the chronic cough that she seemed to have developed as of late, and the way her hands shook from time to time.

Maybe it was that he hadn’t looked close enough at her before, but he couldn’t help but think how she looked like she had aged five years in the short time he had known her. And the thought crossed his mind that he didn’t know how old she really was. Maybe a hard-lived thirty, or maybe ten years older. The kind of woman she was, and the kind of life she lived, made it hard to tell. Women in her profession didn’t stay young long, no matter their years.

She caught him staring at her, so he focused his attention across the street where the big canvas tent that had been the company store had once stood, and at the two men leaning against the rear wheel of the wagon parked there. Both men wore broadbrimmed hats and pistols on their hips, and both men were trying to act casual, as if they had nothing better to do than while away a hot afternoon leaning against a wagon and telling stories. The sunlight flashed for an instant on one of the badges they had pinned on their chests.

Dixie waited to speak until she saw where he was looking and who he was looking at. “Are they still asking you questions about Johnny Tubbs?”

“Not in a few days.” Her voice lost some of its edge and went a shade quieter, as if the two men across the street at the wagon might hear them. “But they’re still asking questions of everyone else left in camp.”

“Don’t know why they’re so all fired up to find out who shot that miserable little peckerwood. Nobody’s missing him and nobody’s complaining. It ain’t like there ain’t plenty of bad men in the Nations for those federal boys to go hunting. They ought to leave you alone. Picking on a poor . . .” His voice trailed off.

“Picking on a poor whore. That’s what you mean, isn’t it?” She was looking right at him again with those green eyes flashing.

“I was about to say ‘poor defenseless woman.’”

“Don’t try and sugarcoat it now.”

“Those marshals think you killed Tubbs. And so do a lot of other people.”

“And why would I kill him?”

“You know why, and almost everybody else has a pretty good idea what he did to you. Ain’t no shame in it, but some would say you had a pretty good motive. I’m not saying you did it, but if you killed him, well, can’t say as I blame you. Might have done it myself if I had caught him.”

“People ought to shut their mouths and stick to their own business.”

“I think . . .”

“What do you think, mister lawman? What do you think, now that they’re calling you Chief and you’ve got all the answers?”

Dixie looked down at the MK&T Railroad Police badge pinned to the lapel of his vest with the little pendant hanging on chains beneath it that said Chief, as if surprised to see it there. “I ain’t made up my mind whether I’m taking the job or not.”

“You pinned on his badge.”

They both knew who she was talking about when she said his badge.

“He’s gone. Told me I had his blessing if that’s what I wanted to do.”

She gave a bitter scoff. “What a load of blarney. You’re fussing at me for considering running Bill Tuck’s saloon, and yet you’re willing to work for Willis Duvall and his railroad? I’d say that’s the pot calling the kettle black.”

“I said I haven’t made up my mind.”

“And that’s what I told you about Tuck.”

“Fair enough,” he said.

“Fair enough,” she replied equally as curtly.

They said nothing to each other for a long spell after that, as if the hot, humid day pressed down on them to the point that even speaking took too much energy. The two U.S. deputy marshals across the street soon gave up their watch and went elsewhere to find some shade or a cool drink of water.

Bill Tuck came up the street a half hour later walking beside a loaded wagon. Several women waved at him from a six-seater surrey with bright red wheels and a canvas sun top as they passed him headed east in the opposite direction of the tracks.

“I guess Sugar Alice and her girls don’t like paying railroad fare,” Dixie said. “Or else those railroad boys wouldn’t swap tickets for a little dose of Sugar Alice’s wares. Either way, Alice looks like she’s going overland to the next camp.”

Red Molly glanced at the buggy load of prostitutes wheeling out of the camp, but her real attention was on Bill Tuck, although she tried to act like she wasn’t watching him.

“Why, good day, Molly,” Tuck said like he was some gentleman on a Sunday stroll after church, rather than a pimp and a saloon owner who everyone in Ironhead Station believed was behind half the bad stuff that had gone on in the construction camp during the past winter and spring.

Neither Molly nor Dixie answered him, and remained leaned back against the wall of the depot house to keep under the limited shade it offered. Dixie adjusted his cap and studied the saloonkeeper.

Tuck, as always, was dressed fashionably in a silk vest with a floral pattern, and bright blue garters worn around the upper sleeves of his white shirt. A gold watch chain hung across the front of that fancy vest, and the white handle of a little pistol stuck out of the opposite slit pocket. He was hatless, and his head was shaved as slick and clean as baby skin. Despite the muggy day, his shirt looked fresh and ironed, and only a few dewdrops of sweat could be seen on his bald head.

He stopped in the glare of the sun and squinted into the shadows at Dixie and Molly. When he squinted, the sharpened, waxed ends of his mustache lifted and twitched like cat whiskers. “You thought on my offer?”

“Some,” Molly answered.

Tuck looked at the wagon where the marshals had stood earlier, and Dixie knew that Tuck somehow had known what the marshals were up to that day. Knowing the whereabouts of lawmen was probably a requirement for a man of his questionable leanings.

“Well, don’t think too long on it,” Tuck said. “We’re about loaded up.”

“I’m still thinking on it,” Molly answered, and her voice was flat and emotionless.

Tuck laughed. “Who are you fooling, Molly? You’re either staying here and working for me, or you’re going down the tracks to Canadian and working for me there.”

“I’ve got choices.”

“What choices?”

“Maybe I’ll go on to Canadian and go into business for myself.”

He laughed again. “Talk tough all you want, but you and I both know better.”

“I’ll give you an answer when I’m good and ready.”

Tuck looked again to the wagon where the marshals had stood. “Might be if you answer right, I could help you with some of your problems.”

She didn’t reply to him, and Tuck moved on, walking rapidly to catch up with his wagon and shouting orders to his hired help on how he wanted his stuff loaded on the train.

Dixie noted the roulette wheel perched atop Tuck’s wagonload. “Looks like he’s taking most of the saloon with him. Don’t know what he’s leaving you to run here.”

“He knows the real business will be down the tracks at Canadian, but he’s leaving enough behind to keep the doors open long enough to see if those North Fork people get this town off the ground.”

“Town? This?” Dixie said.

And he was remembering and seeing earlier days when he asked it. He was seeing how Ironhead had been in its ugly, boisterous prime, with hundreds of booted men living in the camp they were now tearing down, and the majority of them bellied up to the bar on a Saturday night and swilling down cheap rotgut until they thought they were half man and half alligator and ready to take on any man who said any different. And what it took to keep those hardworking, hard-drinking devils in line, and even more so, what it took to keep a lid on a camp that drew the other, worse kind of human, like flies on a fresh cow patty. They were the kind that followed such places looking for easy pickings and easy prey—dope peddlers, cardsharps, pimps, prostitutes, pickpockets, and holdup men. And worse.

“You know how these end of the tracks boom camps work,” he added with equal disdain and skepticism. “They live hard and die fast, and then the next one springs up and nobody remembers the one before it.”

“All I know is what they’re saying. I heard yesterday that they’re going to build a hotel soon. The Katy is going to fix the depot, and the supply warehouse across the tracks is still here. That means railroad business, and with the wagon roads that come through here . . . Well, maybe they’re right, and this place can make a go of it.”

“A hotel? Nothing but big talk and big ideas.”

“Everything starts with nothing more than talk and ideas,” she said. “Maybe I want to be in on the beginning of something.”

“When did they start calling the next camp Canadian?” he asked. “I didn’t know it had a name, yet.”

“You’re the new police chief, and you don’t know what they’re calling what’s fixing to be your new home?”

“I haven’t talked to the superintendent in a while.” He touched his chest gingerly, as if to remind her of his wound. “This bullet hole has had me under the weather, in case you didn’t notice, plus I needed time to think on things.”

“Call him by his name. You sound like every other kiss-ass on the Katy line calling him the superintendent.”

“Duvall is . . . well, he is what he is,” he said.

“He’s got it coming.”

“Got what coming?”

“Nothing. Just what we all got coming, I guess.”

He noticed the funny way she said that, but didn’t let on like he had. And he thought about Bill Tuck and his fancy vest and that smart-aleck smirk always on his face, like a cat that had just swallowed the canary and with the tail feathers still poking out its mouth. Hard to believe he had come through it all virtually unscathed. If anybody had it coming, it was him, but that wasn’t the way things had to work. What was fair didn’t always have anything to do with the way things were. Dixie had learned some of those lessons as a boy, and more of them in the late war and since. Things happened the way they happened, and a man often couldn’t do a thing to stop them.

His gaze drifted back to the black square and ash pile where Irish Dave’s saloon had been, burnt and gone like the depot house in those days of the past when the Katy railroad was trying to get the trestle bridge built over the South Canadian River, and Ironhead Station truly was the wildest hell-on-wheels construction camp west of anywhere. And he looked beyond the camp to the little knoll with the giant oak trees that had become the camp’s Boot Hill. Fourteen grave markers lay under the spreading arms of those trees. Fourteen men gone, and all kinds of other suffering that couldn’t be marked with tombstones or wooden crosses—that’s what it had taken to build the Katy’s railroad trestle and get the tracks moving on to Texas.

“Irish Dave was one of a kind,” Molly said absentmindedly as she, too, looked at the ash pile where the Bucket of Blood Saloon had burned down.

“You might say Fat Sally was every bit as eccentric.” He laughed and then gave a mock shiver. “Meanest, foulest, toughest woman I ever had the misfortune to run across.”

“Well, they’re both gone now.”

“Gone like Ironhead Station, and maybe we’re the better for it.”

“Maybe. What do you think he would say about all of this?” Dixie knew who she meant—that he again. Him.

He twisted around on the bench and looked at the charred, splintered plank wall behind them. A yellow-stained sheet of paper was tacked there. It read:

The handwritten poster was signed at the bottom by the chief of the MK&T railroad police, Dixie’s predecessor. A pair of bullet holes cut the middle of the paper like the eye-holes in some kind of a mask. And he noticed that somebody had scribbled out the name of Ironhead Station and written something else in place of it.

“What’s that?” he asked, pointing to the crude edit.

“That’s what those North Fork folks are calling it now. Eufaula,” she answered.

“Eufaula?”

“Some kind of Creek Indian word.”

“What’s it mean?”

“I don’t know. I think Agent Pickins and his Indians out at the Ashbury Mission came up with it.”

“Leave it to old Useless Pickins to change a perfectly good name.”

“His name is Euless.”

“That’s what I said, Useless. Everybody calls him that.” Dixie gave something between a grunt and a chuckle. “Now there’s an accurate name if I ever heard one. Never had any use for that whiny preacher.”

“Well, it’s his place now, him and the rest of them that are staying on,” she said.

“Hate to think what we did cleaning this place up was only so that his kind can reap the rewards.”

“Thought you said this place wouldn’t ever amount to anything?”

“I’m just saying . . .”

“There you go again. What are you saying?”

“This is Indian land. White folks have to marry into the tribe or get them a work permit from the Federals to live in the Nations legal-like. Nothing but the railroad right-of-way belongs to the Katy, from what I hear, and all that talk about a three-million-acre land grant has been thrown out the window unless Superintendent Duvall and the money men can sway Congress and the courts to change their minds.”

“Folks are staying, no matter what. There is good farmland here along the river. Plenty of timber for building or for selling. You ought to think on staying yourself. Throw away that badge.”

“Lay down the sword and take up the plow?”

“Something like that.”

“What do you know about farming?” he asked.

“People can learn. We don’t always have to stay the same thing.”

“Well, I followed a plow near half my life, and I never ended up anywhere but at the end of the next furrow, and hungrier than I started.” Dixie stood to his feet stiffly after such a long sit, and making slow work of it and favoring one side of his body.

“Does it hurt much?” she asked.

“A little, time to time, but I’m healing proper. Another week or two and I ought to be right as rain,” he answered. “Lucky the Traveler didn’t shoot more to center, or I wouldn’t be here now complaining.”

The mention of the Arkansas Traveler made her face go still, and he knew what she worrying about and wished he hadn’t said what he said. It was the same thing he had been worrying over for more than two weeks.

The deadliest hired killer to ever kiss a rifle stock, and a man that had put more men under the sod than half the undertakers west of the Mississippi, that’s what they said about the Traveler. And Dixie had reason to know the truth of some of that, for the assassin had put a bullet in him at better than six hundred yards away and put him within a frog hair of the bone orchard. And he was still out there somewhere, hunting, and with a certain killing yet undone—not Dixie, but the man the Traveler really wanted dead. Him.

The engineer had climbed up in the locomotive cab and let off a long blast of his steam whistle. Dixie moved his holstered pistol around to a more comfortable position on his hip and made as if to go.

“Train’s about ready to leave,” he said.

“Yeah. Are you going with it?”

He looked down at the badge on his chest. “I guess that’s what he would do. He always said it was an honest living, even if I’m not sure about the honest part.”

“Where do you think he is right now?”

Dixie stepped to the corner of the depot platform and looked to the west, as if he could see right through the train blocking his view, and as if he could see for days and days ahead into that distance. He looked back at her, and then he looked one last time at that poster of camp ordinances tacked to the wall behind her. He paid particular attention to the signature at the bottom of that poster.

Morgan Clyde, MK&T Chief of Railroad Police. Him.

“I reckon he’s getting by. Morgan’s a hard man,” Dixie said.

“You say that so calmly. And with him out there all alone, and in who knows what kind of trouble.”

“Morgan is used to being alone. I think he’s like that most times, even when he’s got company.”

“You should have gone with him.”

“I know . . . but he said that it was his to do, and nobody else’s.”

“He always says that.”

“The Traveler challenged him to come out and face him, alone and on his terms, or get ambushed here in camp with no fair chance at all. Wouldn’t have it any other way.”

“Men and their damned fool pride. He could have gotten a posse together and ran that Traveler out of the hills. Or he could have got the army to help him.”

“No posse is going to want to hunt the Traveler. Not with him lying out there somewhere in the distance with a rifle likely pointed their way.”

He noticed a tear running down Molly’s cheek, and when she saw him looking at it, she swiped it away and gave him an angry scowl.

“You ever told him how crazy you are about him?” Dixie asked.

“I haven’t, and don’t you go making stuff like that up,” she snapped back at him. “Me and Morgan go way back, that’s all. I’m proud to call him a friend, same as you are.”

“Right.” He rubbed at the whisker stubble on one cheek in an attempt to hide his grin.

“Have you told Ruby Ann you’re leaving?” she threw back at him.

He rubbed that whiskered cheek more vigorously and his grin changed to a grimace. He shifted his feet restlessly, and everything about his pose said he wasn’t going to answer that question.

“Oh, come now, Dixie Rayburn. You’ve got all kinds of wisdom when it comes to other people’s business,” she said. “You know she’s sweet on you.”

“Ruby Ann . . . she’s . . . she’s all messed up right now. I’ve been nice to her during her convalescence, that’s all. She’ll think different when she’s had time.” He stepped off the depot platform and started for the nearest passenger car on the long line of the train. “You’ll tell her I’m gone, won’t you? Explain things?”

“You knew you were going, didn’t you? You already had your belongings on the train.”

“Reckon so. Man’s gotta make a living.”

He was halfway there when he heard her speak again. Maybe she meant him to hear it, or maybe she was only talking to herself.

“I wonder where he is right now?”

Dixie was still thinking about those words when the train rolled and rattled across the high trestle over the South Canadian River a mile and a half south of Ironhead. He looked out the window of the passenger car to the west again, at all that wild country the government had set aside as the Indian Territory, or what some called the Nations. The whole damned territory was meant to replace the land that the government had taken from the Indians elsewhere, but like all things the government messed up, it had become as much a haven for bad men and outlaws of every color and creed as a reservation, and the kind of place where law and order was as scarce as hen’s teeth. A lot could befall a man in that kind of country, and he, like Red Molly, wondered what had happened to Morgan Clyde.

Morgan Clyde lay on his belly behind the dead horse, unmoving, and exactly the same way he had lain for the past two hours. Only one other shot had been fired his way in all that time since the one that had struck his saddle. But that last shot had blown another hole in his dead horse’s belly. The flies and the smell of guts had gotten worse as a result.

The hill where the gunshots had come from ran for a mile or better on the northern horizon. Morgan knew it was only a matter of time before Old Death out there got tired of playing with him and changed positions on that hill, and only a matter of time until he was situated where he could shoot around the dead horse.

Old Death, Morgan didn’t say it, but that’s how he had thought of him for a long time, like an old nightmare that he had somehow gotten on a first name basis with. When people talked of him, they mostly called him the Arkansas Traveler, but Old Death fit better. Every

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...