- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

THE WIDOWMAKER MEETS HIS MATCH

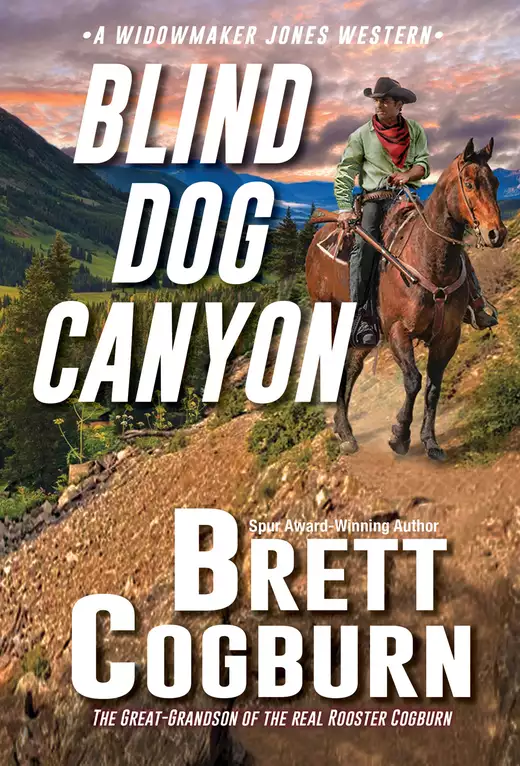

Spur-Award winner and bestselling western author Brett Cogburn—great grandson of the ledgendary Rooster Cogburn—continues his high-octane Widowmaker Jones historical western series.

THEY CALL HIM “THE CUTTER”

Famous for his fancy bowler hat, striped shirts, and double-holstered revolvers, Kirby Cutter is no ordinary gun-for-hire. He’s a cold-blooded professional. The best of the best—and the deadliest of the deadly. Which is why one of the nation’s biggest silver companies hired him. His latest job: To locate a silver claim in the Colorado mountains—and eliminate the competition. His biggest obstacle: The silver is guarded by Newt “The Widowmaker” Jones, a legend in his own right. But Cutter has a wild card up his fancy striped sleeve. His hatchet man is the outlaw Johnny Dial, who’s itching to slaughter Jones for killing his brother. It’s not the only showdown Widowmaker Jones has to deal with. A crazed grizzly is prowling the area, too—and it’s developed a taste for human flesh . . .

One way or another, someone is going to meet their maker. But it sure as hell won’t be the Widowmaker . . .

Praise for Spur Award winner Brett Cogburn

“Fans of frontier arcana will revel in Cogburn’s readable prose and lively characters.”

—Publishers Weekly on Rooster

“Cogburn amazes and astounds.” —Booklist

Release date: October 24, 2023

Publisher: Pinnacle Books

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blind Dog Canyon

Brett Cogburn

Newt Jones sat at a table in a far corner of the dance hall with a half-empty whiskey bottle on the table before him. He was gloriously drunk, although anyone watching him might not have realized his condition. He hadn’t said much, hadn’t danced, and might have gone unnoticed among the crowd if he hadn’t been the kind of man that stood out even when he tried not to. He was tall, true, sitting there in a sheepskin coat and a big black hat. But that was only a part of what drew the eye to him. Beneath that hat brim and tucked down into the wooly collar of his coat was a face that was hard to forget.

The three-piece band on the stage at one end of the hall was currently playing a slow and fiddle-heavy rendition of “My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean” for the third time in less than an hour, and the dance floor was almost unoccupied due to that. It was not an upbeat song to please would-be dancers, especially not the current crowd of railroad men, freighters, ditchdiggers, and the other hard-living, booted sorts who had imbibed more spirits than Newt had. Those men wanted to stomp on the wood floor with a pretty lady and swing her to the ceiling, not stand around and listen to some sad, melancholy song over and over.

The house was selling more liquor while the majority of the crowd stood at the edge of the dance floor waiting, but there was also grumbling, both among the men who had spent their hard-earned money to rent a dance partner and the others who wanted their turn to do the same. Among that crowd were two young men who either had more money or more enthusiasm than their peers, for the two of them had stayed paired up with the same girls for the last hour. They danced to every fast song, and what they lacked in technique they made up for in energy. When they laughed, it was loud enough to be heard above the crowd and the music. One of them let go of the tall, blonde-haired German girl he clutched around the waist, tossed down the mug of beer he held in his other hand, and came across the room to stand in front of Newt’s table.

“Somebody said you are the one that keeps tipping the band to play that song,” the young man said in a chopped, twangy accent that caused one of Newt’s eyebrows to lift slightly.

Newt poured himself more whiskey. It took all of his attention to make the liquid land in the glass.

“I said, Was it you?” the young man asked in a louder voice.

“Something bothering you?” Newt’s face cracked into a grin. He wasn’t a man normally given to grins or smiles, but the liquor was working hard on him.

“You sitting there grinning like a possum eating persimmons, that’s what’s bothering me,” the man said. “And you paying that fiddler a whole ten dollars to keep playing that awful song bothers me worse.”

Newt took another sip of whiskey and watched the fiddle player as if he hadn’t heard the young man standing in front of him.

“Mister, you see that pretty lady over there watching us? I spent my last three dollars to dance with her.”

Newt threw back his head and sang, “Oh, bring back, bring back, bring back my Bonnie to me.”

His voice, while not good, was at least somewhat on key, and what he lacked in style, he made up for in volume. The fiddle player gave him a tolerant nod from the stage.

The other young man still back with the girls took a step closer. “What’s the matter, Tandy?”

“Trying to talk some sense into this ’un,” the one at Newt’s table called back to his partner.

They looked enough alike to be brothers, lean and about the same height, with sandy brown hair that curled out from under their hats. And both of them had that same accent.

“Listen, friend, I don’t want to fight,” the one by Newt’s table said. “Ol’ Tully over there, he’s got a temper finer than a frog hair split three ways and tapered on both ends. What say you quit tipping that fiddler so we can have us some real dancing music?”

“Fight?” Newt slurred, as if that was the only word he had heard, and reached out and wrapped a big hand around the whiskey bottle.

Even in the poor light of the dance hall, the young man could see the battered and scarred knuckles on the big hand that gripped the bottle. And the scars on Newt’s face were more noticeable than those on his fists. The marks on his cheekbones, chin, and eyebrows stood out on his suntanned skin like little cracks and seams in the fault vein of some hard rock mine shaft. His nose had been broken badly sometime in the past, perhaps more than once, and one cauliflower ear told that he had been clubbed there, as well.

Two things happened at that very moment. First, the band finished the song and broke straight into a fast-tempo banjo version of “Camptown Races” that caused the crowd to whoop with joy and sent many couples back out on to the dance floor. Second, a man even bigger than Newt came through the front door at the far end of the hall. He waded through the crowd toward Newt’s table, and in the process accidentally bumped into a man near the bar.

The big man coming Newt’s way took hold of the man he had crashed into in order to keep that one from falling. Words were said between them that Newt couldn’t hear. Then the big man continued on his way until he stopped to stand behind the young man who had, until then, been talking to Newt and making his complaints about music choices known.

“Have a seat,” Newt said, and jerked a chair beside him out from under his table.

The chair fell over, but the giant newcomer sidled past the young man in his way, stood the chair back up, and sat down. The wood creaked beneath his weight.

The young man looked from one of them to the other, then turned on his heel and went back to the dance girls and his partner. He was shaking his head as he walked away.

“Did you see the size of that Indian?” he said to the others when they were reunited.

Newt heard what the youngster said and gave the man in the chair beside him a cursory glance. The kid was right. Mr. Smith was definitely the biggest Indian that Newt had ever seen or known. To say the Mohave was big was an understatement. Newt stood six feet three in his socked feet, yet Mr. Smith was taller. And it wasn’t only the height that made him seem like such a giant. The man’s upper arms were the size of most men’s thighs. He was so large at the chest and shoulders that he had a hard time finding warm winter wear that fit him, finally settling for a buffalo coat he had bought from a Ute woman on their way up through the mountains. That bulky, incredibly heavy coat, with its curly buffalo hair and hanging to the back of his knees, made Mr. Smith’s bulk seem even more expansive.

Mr. Smith took off his bowler hat, brushed a light dusting of snow from it, and set it on the table. His long, crow-black hair was bound behind his neck with a leather thong. He shrugged out of his buffalo coat and let it lie on the back of his chair. While the dance hall was a bit drafty and almost chilly in places, that heavy robe would see a bull buffalo through a blizzard. Newt didn’t know how Mr. Smith could stand to wear it, either inside or outside. The thing must have weighed thirty pounds.

Newt blinked and watched the big Mohave carefully straighten the black suit coat he wore under the buffalo hide. The silk tie around his shirt collar was knotted and arranged as neatly as ever. Newt chuckled for the thousandth time at Mr. Smith’s fastidious, odd ways.

“Have a drink.” Newt shoved the whiskey bottle toward his friend.

“I do not want your whiskey.” Mr. Smith’s somewhat guttural accent may have been different, but his attempt at concise diction and his careful choice of words when speaking his second tongue would have done an English butler proud. It didn’t fit with the rest of him any more than his fancy black suit.

In Newt’s opinion, Mr. Smith was a conundrum, but that’s what he liked about the man, at least sometimes. Newt pushed the bottle toward him again.

Mr. Smith looked at the bottle and then at Newt. “You’re drunk.”

“Highly,” Newt said, with another grin.

Mr. Smith began to watch the dancers and sat that way while Newt finished his current glass of whiskey. The Mohave’s tattooed face was oddly tranquil and without expression, and it was hard to tell what he thought of the proceedings.

Newt had long since grown used to the tattoos, as well as Mr. Smith’s stoic approach to life. The Mohave’s face, like much of his upper body, was inked in blue-black symbols that perhaps only another of his tribe could interpret. Chevron-like bars lay across the breadth of his forehead, and T-shaped designs of dots and lines ran down from both cheekbones. Swirled designs decorated his broad, blunt chin.

“Why do you not dance like the other men?” Mr. Smith asked.

“Never was much of a dancer,” Newt replied.

“Then why did you come here?”

“I like listening to the music.”

“The man you seek is at the hotel waiting to talk to you,” Mr. Smith said.

“Is he, now?” Newt answered. “If you’re worried about him, why don’t you go back and tell him I’ll talk to him when I’m through here.”

Mr. Smith gave a deep grunt. “You have a strange way of dealing with a man who you expect to hire you.”

“I’m having fun. Try to have some yourself.”

Their conversation was interrupted when three men came to their table. The one in the middle was the same one whom Mr. Smith had bumped into earlier, and he pointed a finger at the Mohave.

“We don’t allow Indians in here,” the man said.

“That’s right,” one of those beside him said.

Newt blinked twice and waited for the men to come into proper focus. He wanted to make sure there were actually three of them. “Who do you mean by we? All of you, or just you?”

“What?” the man in the middle asked.

“That’s what I thought,” Newt slurred.

“Listen here,” the same man said.

“No, you listen here.” Newt jerked his head at Mr. Smith beside him while he gave the men before him another goofy grin. “I’m going to do you a favor.”

The man in the middle of the three smirked. “And what favor is that?”

“I’m going to whip you before he can.” Newt’s head almost rattled the lantern hanging over his table off its hook when he stood, and his thighs caught the edge of the table and knocked it back several inches. The whiskey bottle fell over, and what was left of its contents slowly trickled out onto the tabletop.

The man in the middle drew back a fist to hit Newt, but in doing so his elbow struck one of the two young men standing behind him, the same one that had come to Newt’s table earlier to complain about the music. That elbow also almost knocked down one of the dance girls and spilled a drink all over her pretty dress.

“Watch it!” one of the two youngsters said, and then promptly planted a straight right on the gentleman’s nose.

From there, the fight was on. Newt swung a haymaker from well back behind him at the man remaining closest to him. The blow was surprisingly fast for someone almost too drunk to stand. However, Newt’s aim was more affected by the whiskey than his speed was. His punch missed badly and went right over his intended victim’s head. The follow-through put him off-balance, and he crashed across the table and eventually rolled up under what was now a full-fledged brawl between the two youngsters and other men in the crowd.

He almost got back to his feet, but the German girl chose that moment to take a wild swing with the thick glass beer mug she held. Instead of striking her intended victim, she hit Newt in the back of the head. She was a strong, buxom lass, made stronger by helping her father at his brewery outside of town when she wasn’t dancing and pushing drinks for a living. Besides being able to curse quiet loudly in her parent’s native tongue while she fought, she also packed a wallop. Newt’s felt hat cushioned some of the blow from the beer mug, but it was still enough to tip him over onto his face.

Somebody stomped on his fingers while he was down, then somebody else kicked him in the belly. Next there came the sound of another woman screaming, the grunts of straining men, and the dull, fleshy thuds of landing blows, all mixed with the shatter of breaking glass and the scrape of overturned tables and chairs on the wood floor.

The fight eventually moved away from Newt for some reason and gave him standing room. He managed to get his legs under him, but the world was spinning too fast to find his balance. He toppled again like an axe-cut tree, though he hardly felt any pain when he crashed back to the floor.

Hands took hold of him, big hands, and then there came the sensation of rising into the air as if by magic. He was still pondering on how that happened as Mr. Smith tossed him belly-down over one shoulder and started carrying him out of the dance hall.

“Let me down. I’ll take the big ones and you take the little ones,” Newt said.

He tried once to lift himself from the waist to better see what was going on around him, but he couldn’t manage that feat and slumped head-down again with both arms dangling down Mr. Smith’s back. He was still being carried that way when Mr. Smith went out the door and onto the dark street.

Behind them, the two young men who didn’t like Newt’s music backed out the door. A beer bottle thrown at them from inside barely missed them and struck the cold, hard street and ricocheted away.

“Get ’em!” Somebody shouted from inside the dance hall.

“Put me down,” Newt mumbled as he came to life again and squirmed on Mr. Smith’s shoulder.

Mr. Smith kept walking without complying with his request.

A pistol appeared in one of the young men’s hands. The roar of that revolver was the last thing Newt remembered because it was at that very moment he passed out.

The old boar grizzly wasn’t big as such bears went, but the grizzlies in the San Juan Mountains had never achieved the scale of their cousins farther north. Perhaps seven feet long from his nose to the tip of his stub of a tail, he might have weighed six hundred pounds. He would have been heavier if he hadn’t been so shockingly thin. So thin, in fact, that his emaciated rib bones showed even through the shagginess of his winter coat. And that brown fur, tinted with silver on the tips along his back and neck, was matted and tangled. On one shoulder there was a seeping wound that had left a dried crust of old blood and serum and pus.

The hunger and the pain had almost driven him mad, and that madness had him on the move. His broad, massive head swung left and right as he lumbered and limped slowly out of the edge of the timber into the morning sunlight and onto the bare slope of the mountain leading down to the river. The pads of his giant feet hardly made any sound at all on the thin dusting of snow beneath them.

He moved with the wind in his face, and his keen nose searched for the scent of food. Twice he stopped to turn over rocks and search for grubs or insects he might find hiding. Some of those rocks were very large and heavy, but the great hump over his shoulders gave him power, even in his weakened condition, and he hooked his five-inch front claws under those rocks and flipped them over with ease.

The few grubs he found did little to satisfy his hunger, and he gave a low, rumbling growl of frustration. Adding to his torment was the certainty of the coming winter. It was going to snow soon, and snow a lot. With the snow would come the bitter cold, but how he knew that was a mystery. Maybe it was instinct or some magical foresight, or maybe the shortened daylight hours and the dropping temperatures of the past few days and nights triggered some chemical or physiologic working within him that acted like a sixth sense for the seasons. Whatever it was, it told him he should already be curled up inside his den high up on some north-facing slope and starting the long sleep to spring. Normally, he would have been.

The summer berries and tubers and roots and grasses should have seen him prepared. Perhaps some squirrel’s stolen hoard of seeds and nuts, a nice fat trout plucked from some stream, or the occasional elk calf caught and devoured would have added to his fat layer and made him well-prepared to live on those reserves through hibernation. But the warm seasons had come and gone, and nothing had been easy.

Twenty-five years he had reigned as the king of the food chain along the headwaters of the Rio Grande, but now he was coming to the end. Age, aching joints, and the bad teeth in his mouth had something to do with that, however, it was his wound that sped the ravages of time.

It was the man creatures who had hurt him, the strange, noisy, two-legged beasts he occasionally came across. There had been few men in the mountains in his youth, but there came more and more of them with each year. They were men with pale skins, and they made bigger fires and more noise than the brown skins who had come first. It seemed their scent trails were everywhere except the highest, roughest places. And in his later years, as he became slower and less nimble, he had learned that where men camped there was likely to be easy food. Taking it from them was no different from taking a kill away from wolves or coyotes, or any other predator smaller than himself.

But he had not been raiding one of their camps when he came across the men who wounded him. He had found an especially heavy-laden and delicious patch of buffalo berries among a thin stand of quaking aspens one morning and had been so busy eating the juicy, orange-red fruit that he didn’t notice the approach of the two men and the horses they rode up on. They were almost on top of him before he rose up on his hind legs to peer at them over the low brush. Then there had come a loud sound like the crack of thunder and a puff of fire smoke, and something struck him hard in the shoulder, tearing a hole in his flesh and staggering him. Another of those loud noises came and there was a buzzing in the brush beside him like the passing of an angry bee. By then he was already charging the men. They fled from him and their horses were swift, even over the rough mountain trail, but he did manage to rake his claws across the hindquarters of one of the horses before they escaped him. He stood again and roared his victory as they disappeared down the mountain.

Then the pain had hit him as his adrenal gland quit pumping battle rage, and one of his front legs wouldn’t work right. Limping and in shock, he found a thicket to rest in, and there he lay for days, hot and feverish and with his wound aching horribly. Only his thirst and hunger finally drove him from his bed. Though he lived, he was not the same. The bullet wound in his shoulder would not heal, no matter how much he licked it. It stank of dead flesh, and the blowflies followed him.

Then the elks’ calving season came and went, and he caught not a single new calf. Nor did he catch any deer fawns where they tried to hide in the grass. Finding food had always taken much traveling, but he traveled less than ever.

The old bear squatted on his rump and lifted his nose higher. There came a tantalizing smell, only a small whiff. It was a scent he knew from before, though it was something he had only fed upon on a few occasions, all of them in his later years. It was the smell of sheep. The thought of ripping greasy, fat mutton off its bones caused him to run his tongue over his lips.

Though his sense of smell was keen, the old bear’s eyesight had grown worse as he aged. No matter, he had always trusted his nose more than his eyes. He moved down the mountain, pausing often to smell the wind and searching for the sound or sight of the sheep he knew were close to him.

He heard the bleating before he saw the sheep. They were grazing not far below him. They must have seen or sensed his presence because they quit grazing and began to form a tight flock, milling about with their white, wooly bodies crammed together.

A great strand of drool slid from the old bear’s mouth as he stalked closer. Experience had taught him that where there were sheep there were men, but he was too hungry to remember that detail or care. Sheep were easy to catch. Easier than any of the prey he knew. Even easier than digging marmots out of their holes when he could find some for a quick snack.

An alder thicket screened his movements and gave him cover to stalk from. His round little eyes peered through the limbs of a small bush, waiting for the right moment. By then, he was within sixty yards of the sheep. He was so focused on his prey that he didn’t notice the sheepherder sitting on the shaggy little pony uphill from the herd. He also didn’t notice the sheepdog, but the collie was no bigger than a coyote and could not stop him. Even had there been five men and as many dogs, it would not have changed what was about to happen, for nothing then and there could have distracted him from the urge to kill and feed.

He burst from the thicket and charged toward the flock. For a moment, his limp was all but gone, and he was as fleet-footed and horrible in a charge as he had been in his youth.

Newt rested his temple in one hand and squeezed slightly against the throb of the headache that he had woken with. He closed his eyes for a moment and then opened them to look again at the fellow across from him over the mug of steaming coffee he was nursing.

“There’ll be a fellow waiting for you at Wagon Wheel Gap,” the one across the table said. “People around these parts call him Happy Jack. He’s an old prospector that knows these mountains like the back of his hand. He’ll show you to the claim.”

Newt closed his eyes again and let the coffee steam waft across his face. The dining room in the Windsor Hotel was sparsely populated that morning, and Newt had hoped to have his coffee in peace and recover from the previous night’s debauchery.

“Are you listening to me?” the man asked.

“Saul, would you quit talking so loud?” Newt asked back.

Saul Barton was old enough to have gone white-headed, but still young enough that he hadn’t lost his edge or his physical strength. He looked less like a man who had made a couple of fortunes locating silver and gold lodes and then selling them to the big mining interests. That morning he was wearing a plain white shirt tucked into plain brown wool pants, in turn tucked into a pair of plain, sturdy lace-up work boots that were scuffed and scarred enough to show they had been somewhere. The only things that hinted at his success were the gold cigar case lying on the table in front of him and the big, gold-nugget ring he wore on his calloused right hand.

He was a short man, yet his serious nature and the intensity of his gaze were far bigger in scale. And he had never been known as a patient sort, not since his first days out in the gold fields when Colorado was nothing but a territory, before the war, and when he had been just another fortune seeker panning away on a hard-luck placer claim like all the rest of the fools. But his persistence had paid off, no doubt largely due to his eternal optimism and a work ethic that would put beavers to shame. It had been a common saying back in the first mining camp Newt had lived in that Saul thought working only twenty-four hours a day was pure laziness.

“I’d say you were suffering from one hellishly bad hangover, but knowing you, you’re still half drunk,” Barton said.

“Let it be, Saul,” Newt said. “I came just like I said I would.”

“You’re late,” Barton replied. “I should have left for San Francisco two weeks ago.”

“It was a long ride from Yuma.”

“Never cared for that desert.”

“I’m not partial to it myself, now that I’ve been there,” Newt said, then gave a quick look around the room that made his head hurt worse. “Where’s Mr. Smith?”

“Is the Mr. Smith you speak of that big Indian who carried you to your room last night?”

“He’s working with me.”

“I gathered that,” Barton said. “Odd name for a Mohave, but I suppose we couldn’t even pronounce his real name. Never seen any of his kind up this way. Peculiar tribe is my impression, and that’s putting it mildly.”

“Oh, he’s peculiar, but he’s the kind you want to ride the river with,” Newt said.

“I imagine those tattoos on his face take some getting used to.”

Newt shrugged but gave no reply.

Barton played with his cigar case, spinning it around on the table instead of drinking his own coffee. After a while he looked up at Newt again. “I told you I wanted you to bring at least three men with you.”

“I’ve got me and Mr. Smith, so far.”

Barton leaned back in his chair. “This town’s overpopulated with winter coming, and there are plenty of men down from the high country to lay up and wait for spring. I’m sure you can find a couple who will do.”

“I’ll see about it.”

Barton pointed at a scrape on Newt’s forehead and then at the swollen pointer finger on Newt’s left hand. “I understand you got in a little ruckus over at the dance hall last night.”

Newt sat up straighter without the movement causing his head to hurt much worse. “I wouldn’t call it a fight. More of a misunderstanding.”

“The city marshal is looking for two men who shot up the place.”

“We never fired a shot,” Newt said, and then gave a thoughtful grimace. “At least I don’t think we did. To tell you the truth, I don’t recollect much about it.”

“Still the hardheaded scrapper you always were, aren’t you? Do you still step in the prize ring when you get the chance, or is brawling in taverns and whiskey dives the only fight you can find?”

Newt wrinkled his face and avoided the question. “Your telegram said you would pay an advance.”

Barton produced a yellow paper envelope and pushed it across the table to Newt. “There’s money in there to pay you and three more men your first month’s wages. Three dollars a day, like I promised. You’ll get the rest of it when I come back in the spring.”

“Have you already filed the claim?”

“I have.”

“You’re worried or you wouldn’t be paying the money you’re paying and needing so many men.”

“There were two other parties working the area this past summer. And I got the distinct impression they were spending more time following me than prospecting.”

“That’s what happens when you’re the man with the supposed magic touch for finding the next big strike.”

“Maybe, but I have a suspicion that those prospectors were backed by one of my competitors,” Barton said.

“And you’re worried one of those competitors will try to move in on you?”

“I’m simply buying some insurance.”

“You must think you have a real wing-dinger of a strike.”

“Let’s say it shows some promise,” Barton said. “You’re to let nobody on that claim. Nobody. I don’t want anyone snooping around or maybe getting ideas that I can’t hold what’s mine.”

Newt studied Barton. “If you’re so sure about this one, why are you going to San Francisco instead of staying here to see to this yourself?”

Some of Barton’s temper showed itself them, just a slight hint of irritation before he smothered it and hid it away. He wasn’t a man who liked to be questioned. “Developing a mine is not a cheap matter, and I need to gather investors.”

Newt weighed what Barton had said against what he hadn’t said.

Barton waved a hand in the air as if that alleviated all concerns. “If I had to guess, I would say you and whoever goes with you will make a tidy profit for doing nothing other than lying around all winter and getting fat.”

“How far away is this Willow Creek? How big of a town is it?”

“No town there.”

“No tent city?”

“I’m the first one there.”

“What about supplies?”

“There’s already a cache at the claim, and Happy Jack will have more for you when you get to Wagon Wheel Gap.”

“That all?” Newt asked.

Barton got up from the table. “Except to wish you good luck.”

“Same to you.” Newt stayed seated.

“I’ve already seen to your hotel bill,” Barton said.

“That’s kind of advertising that I’m working for you, isn’t it?”

Barton brushed off the question simply by not answering it and started out of the dining room. “I’ve got a train to catch.”

Newt finished his coffee, refused another mug from one of the waitresses, and went up to his hotel room and packed his belongings. It took him longer than it should have because he was pondering the job he had just taken.

The thermometer mounted outside the hotel door read twenty-nine degrees when Newt went outside, and there was a light dusting of snow. He bunched his wool coat collar up around his neck and trudged toward the livery barn and corrals on Fifth Street.

Mr. Smith was waiting there with their horses already saddled. Newt held out a hundred dollars in greenbacks he had taken from the envelope Saul Barton had given him.

“You keep it,” Mr. Smith said, with a shake of his head.

“Take it, it’s yours. Start a fire with it if that’s what suits you,” Newt replied. “Or give it to pretty girl or tip a blind piano player. I don’t care.”

Mr. Smith took the money but muttered something in his native tongue. Newt had no idea what the Mohave said.

“Speak English if you’re going to argue.”

Mr. Smith ignored him and tightened the cinch on the big, black gelding standing tied to the corral fence. The horse had hooves the size

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...